6.3.3 Distal Radius and Wrist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

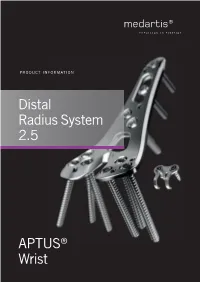

Distal Radius System 2.5

PRODUCT INFORMATION Distal Radius System 2.5 APTUS® Wrist 2 | Distal Radius System 2.5 Contents 3 A New Generation of Radius Plates 4 One System for Primary and Secondary Reconstruction 6 ADAPTIVE II Distal Radius Plates 8 FPL Plates 10 Hook Plates 11 Lunate Facet Plates 12 Rim Plates 13 Fracture Plates 14 Correction Plates 15 Volar Frame Plates 16 Extra-Articular Plates 17 Small Fragment Plates 18 Dorsal Frame Plates 19 XL Plates 20 Distal Ulna Plates 21 Fracture Treatment Concept 22 Technology, Biomechanics, Screw Features 24 Precisely Guided Screw Placement 25 Instrument for Reconstruction of the Volar Tilt 26 Storage 27 Overview Screw Trajectories 29 Ordering Information 47 Bibliography For further information regarding the APTUS product line visit: www.medartis.com Medartis, APTUS, MODUS, TriLock, HexaDrive and SpeedTip are registered trademarks of Medartis AG / Medartis Holding AG, 4057 Basel, Switzerland www.medartis.com Distal Radius System 2.5 | 3 A New Generation of Radius Plates Why is a new generation of radius plates needed? Distal radius fractures are the most common fractures of the stable plate systems have enabled open reduction and inter- upper extremities. The knowledge of these fractures has grown nal fixation to become an established treatment method for enormously over the last years. Treatment concepts have like- intra- and extra-articular distal radius fractures. These sys- wise been refined. It is now generally accepted that the best tems have enabled even severe extension fractures with dor- possible anatomical reconstruction of the radiocarpal joint sal defect zones to be precisely repositioned and treated with (RCJ) and distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) to produce a func- osteosynthesis via volar access without the need for additional tional outcome is a requirement. -

Medical Policy Ultrasound Accelerated Fracture Healing Device

Medical Policy Ultrasound Accelerated Fracture Healing Device Table of Contents Policy: Commercial Coding Information Information Pertaining to All Policies Policy: Medicare Description References Authorization Information Policy History Policy Number: 497 BCBSA Reference Number: 1.01.05 Related Policies Electrical Stimulation of the Spine as an Adjunct to Spinal Fusion Procedures, #498 Electrical Bone Growth Stimulation of the Appendicular Skeleton, #499 Bone Morphogenetic Protein, #097 Policy Commercial Members: Managed Care (HMO and POS), PPO, and Indemnity Members Low-intensity ultrasound treatment may be MEDICALLY NECESSARY when used as an adjunct to conventional management (i.e., closed reduction and cast immobilization) for the treatment of fresh, closed fractures in skeletally mature individuals. Candidates for ultrasound treatment are those at high risk for delayed fracture healing or nonunion. These risk factors may include either locations of fractures or patient comorbidities and include the following: Patient comorbidities: Diabetes, Steroid therapy, Osteoporosis, History of alcoholism, History of smoking. Fracture locations: Jones fracture, Fracture of navicular bone in the wrist (also called the scaphoid), Fracture of metatarsal, Fractures associated with extensive soft tissue or vascular damage. Low-intensity ultrasound treatment may be MEDICALLY NECESSARY as a treatment of delayed union of bones, including delayed union** of previously surgically-treated fractures, and excluding the skull and vertebra. 1 Low-intensity ultrasound treatment may be MEDICALLY NECESSARY as a treatment of fracture nonunions of bones, including nonunion*** of previously surgically-treated fractures, and excluding the skull and vertebra. Other applications of low-intensity ultrasound treatment are INVESTIGATIONAL, including, but not limited to, treatment of congenital pseudarthroses, open fractures, fresh* surgically-treated closed fractures, stress fractures, arthrodesis or failed arthrodesis. -

Pearls and Pitfalls of Forearm Nailing

Current Concept Review Pearls and Pitfalls of Forearm Nailing Sreeharsha V. Nandyala, MD; Benjamin J. Shore, MD, MPH, FRCSC; Grant D. Hogue, MD Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA Abstract: Pediatric forearm fractures are one of the most common injuries that pediatric orthopaedic surgeons manage. Unstable fractures that have failed closed reduction and casting require surgical intervention in order to correct length, alignment, and rotation to optimize forearm range of motion and function. Flexible intramedullary nailing (FIN) is a powerful technique that has garnered widespread popularity and adaptation for this purpose. Surgeons must become familiar with the technical pearls and pitfalls associated with this technique in an effort to prevent complications. Key Concepts: • Flexible intramedullary nailing is a useful technique that is widely utilized for most unstable both-bone forearm fractures except in the setting of highly comminuted fracture patterns or in refractures with abundant intrame- dullary callus formation. • Proper contouring of the rod prior to insertion and bending of the tip will help decrease the risk of malunion and facilitate rod passage across the fracture site. • The surgeon must be aware of the numerous pitfalls that are associated with flexible intramedullary nailing and the methods to mitigate each complication. Introduction Flexible intramedullary nailing (FIN) offers several key As enthusiasm grows for FIN as a treatment for pediatric advantages for the management of those pediatric fore- forearm fractures, surgeons must also clearly understand arm fractures that are not amenable to closed treatment. the technical nuances, controversies, and strategies to These advantages include cosmetic incisions for nail in- mitigate complications associated with this technique. -

Sustentaculum Lunatum: Appreciation of the Palmar Lunate Facet in Management of Complex Intra-Articular Fractures of the Distal Radius

A Review Paper Sustentaculum Lunatum: Appreciation of the Palmar Lunate Facet in Management of Complex Intra-Articular Fractures of the Distal Radius Ebrahim Paryavi, MD, MPH, Matthew W. Christian, MD, W. Andrew Eglseder, MD, and Raymond A. Pensy, MD key role in restoring the anatomy of the palmar distal radial Abstract metaphysis during internal fixation. This fragment in com- Fracture of the distal radius is the most common wrist minuted fractures was first ascribed special importance by injury. Treatment of complex intra-articular fractures of Melone5 in his description of common fracture patterns. In the distal radius requires an accurate diagnosis of the the present article, we describe the anatomical characteristics fracture pattern and a thoughtful approach to fixation. of the sustentaculum lunatum and the clinical relevance of We propose a new term, sustentaculum lunatum, for this fragment to management of fractures of the distal radius. the palmar lunate facet. The sustentaculum lunatum deserves specific attention because of its importance Classification in load transmission across the radiocarpal joint. It is A variety of classification systems have been proposed to char- acterize and guide treatment of fractures of the distal radius. also key to restoring the anatomy of the palmarAJO distal The earliest descriptions of fracture patterns were presented by radial metaphysis during internal fixation. We provide Castaing6 and Frykman7 in the 1960s. The Frykman classifica- a review of the structure and function of the susten- tion historically has been popular but is limited in accuracy in taculum lunatum and describe fixation techniques. This its characterization of fragments and their displacement and is article is intended to promote awareness of this frag- limited in its ability to guide treatment. -

Treatment of Distal Radius Fractures – Clinical Outcome, Regional Variation and Health Economics

From THE DEPARTMENT OF CLINICAL SCIENCE AND EDUCATION, SÖDERSJUKHUSET Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden TREATMENT OF DISTAL RADIUS FRACTURES – CLINICAL OUTCOME, REGIONAL VARIATION AND HEALTH ECONOMICS Jenny Saving Stockholm 2019 All previously published papers were reproduced with permission from the publisher. Published by Karolinska Institutet. Printed by Eprint AB 2019 © Jenny Saving, 2019 ISBN 978-91-7831-339-6 Treatment of distal radius fractures – clinical outcome, regional variation and health economics THESIS FOR DOCTORAL DEGREE (Ph.D.) By Jenny Saving, MD Principal Supervisor: Opponent: MD, Associate Professor Anders Enocson MD, Professor Lars Adolfsson Karolinska Institutet University of Linköping Department of Clinical Science and Education Department of Clinical and Experimental Division of Orthopaedics Medicine Södersjukhuset Examination Board: Co-supervisor(s): MD, Professor Hans Mallmin MD, PhD, Cecilia Mellstrand Navarro Uppsala University Karolinska Institutet Department of Surgical Sciences Department of Clinical Science and Education Section of Orthopaedics Division of Hand Surgery Södersjukhuset MD, Associate Professor Rüdiger Weiss Karolinska Institutet MD, Professor Sari Ponzer Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery Karolinska Instiutet Karolinska University Hospital Department of Clinical Science and Education Division of Orthopaedics MD, Professor Olof Nilsson Södersjukhuset Uppsala University Department of Surgical Sciences Section of Orthopaedics To my family 3 4 ABSTRACT A distal radius fracture (DRF) remains the most common fracture encountered in health care. DRFs have traditionally been treated with a plaster or surgically with percutaneous methods. Since the end of the 20th century, when internal fixation with a volar locking plate (VLP) was introduced, the incidence of DRF surgery in general and of plating in particular have increased markedly. -

Metacarpal Fractures

METACARPAL FRACTURES BY LORYN P. WEINSTEIN, MD, AND DOUGLAS P. HANEL, MD The majority of metacarpal fractures are closed injuries amenable to conservative treatment with external immobilization and subsequent rehabilitation. Internal fixation is favored for unstable fracture patterns and patients who require early motion. Percutaneous pinning usually is successful for metacarpal neck fractures and comminuted head fractures. Shaft and base fractures can be treated with pinning or open reduction and internal fixation; the latter, being more rigid, allows early rehabilitation. External fixation has a limited yet defined role for metacarpal fractures with complex soft-tissue injury and/or segmental bone loss. The recent development of bioabsorbable implants holds promise for skeletal rigidity with minimal soft-tissue morbidity, but long-term in vivo data support- ing the use of these implants is not currently available. Copyright © 2002 by the American Society for Surgery of the Hand arly treatment of metacarpal fractures was lim- Surgical techniques rapidly expanded to include ret- ited to the only tools available: manipulation rograde fracture pinning, intramedullary pinning, and Eand casting. The discovery of percutaneous transfixion pinning. Many of the K-wires in use today fracture fixation near the turn of the century opened have the same diamond-shaped tip and sizing speci- up a new world of possibilities. It was 25 years after fications as the original design. Bennett’s original manuscript that Lambotte de- The first plate and screw set for the hand was scribed the first surgical stabilization of a basilar introduced in the late 1930s. By today’s standards, the thumb fracture by using a thin carpenter’s nail.1 By Hermann Metacarpal Bone Set was quite lean; it 1913, Lambotte had authored a fracture text with included 3 longitudinal plates of 2, 3, and 4 holes, a multiple examples of pinning, wiring, and plating of drill, screwdriver, and 9 screws.1 Improvements in hand fractures. -

Distal Humerus Lateral Condyle Fracture and Monteggia Lesion in a 3-Year Old Child : a Case Report

Acta Orthop. Belg., 2008, 74, 542-545 CASE REPORT Distal humerus lateral condyle fracture and Monteggia lesion in a 3-year old child : A case report Rupen DATTANI, Surendra PATNAIK, Avdhoot KANTAK, Mohan LAL From East Surrey Hospital, Surrey, United Kingdom We describe a case of a Monteggia fracture disloca- DISCUSSION tion and an ipsilateral lateral humeral condyle frac- ture in a 3-year-old child. This is a rare combination Lateral condyle physeal fractures comprise 17% of injuries with no previously reported cases in the of all paediatric distal humerus fractures with a literature. This case emphasises that when a fracture peak incidence at 6 years of age (8). The mechanism is detected around an elbow there should be a high of injury is either an avulsion by the pull of the index of suspicion for other injuries in the region. common extensor origin owing to a varus stress Keywords : Monteggia fracture dislocation ; fracture of exerted on the extended elbow (‘pull off’ theory) or the humeral condyle ; elbow dislocation ; humerus a fall onto an extended upper extremity resulting fracture. in an axial load transmitted through the forearm, causing the radial head to impinge on the lateral head (‘push off’ theory) (2). Milch classified these fractures into two types (12). In type I injuries, the CASE REPORT fracture line courses lateral to the trochlea and into the capitello-trochlear groove representing a Salter- A 3-year-old boy presented to the emergency Harris type IV fracture : the elbow is usually stable department following a fall from a height onto his because the trochlea is intact. -

Palmar Plating of Distal Radius Fractures – Pearls and Pitfalls

Palmar Plating of Distal Radius Fractures – Pearls and Pitfalls Michael S. Bednar, M.D. Chief, Hand Surgery Professor, Dept. of Ortho Surgery & Rehab Loyola University – Chicago Disclosure n Consultant – Biomet/Zimmer Evolution in Treatment of Distal Radius Fractures 1 External Fixation and Percutaneous Pinning External Fixation and Percutaneous Pinning External Fixation 2 Percutaneous Pinning Percutaneous Pinning Old ORIF concept: n Dorsally displaced = Dorsal plate n Palmarly displaced = Palmar plate 3 Goals of Treatment n ORIF n Indications n Displaced palmar intra and extra- articular fractures ORIF n Palmar Barton and Smith Fractures n ORIF is accepted form of treatment n Palmar plate is well tolerated n Exposure radial to FCR has low morbidity 4 Cohort Studies Volar Fixed Angle n Orbay, J. L., Fernandez, D.L. (2002). 31 partients n Kamano, M., Y. Honda, et al. (2002). 33 patients Follows the contour of the subchondral bone Pegs and screw locked into plate support articular surface when placed directed under the subchondral bone. 5 Distally angled pegs neutralize dorsal forces Joint Reaction Force §.Volar buttress neutralizes volar forces Volar locking plating indications • Dorsal or palmar angulation • Intra-articular fractures • Comminuted fractures • Osteopenia Volar locking plating indications • Dorsal or palmar angulation • Intra-articular fractures • Comminuted fractures • Osteopenia 6 3 Months Post OP Wrist Fractures = ORIF 7 ORIF 8 No metal over radial styloid, causes tendon ruputure Complications – Wrong Fracture Type n -

Upper Extremity Fractures

Department of Rehabilitation Services Physical Therapy Standard of Care: Distal Upper Extremity Fractures Case Type / Diagnosis: This standard applies to patients who have sustained upper extremity fractures that require stabilization either surgically or non-surgically. This includes, but is not limited to: Distal Humeral Fracture 812.4 Supracondylar Humeral Fracture 812.41 Elbow Fracture 813.83 Proximal Radius/Ulna Fracture 813.0 Radial Head Fractures 813.05 Olecranon Fracture 813.01 Radial/Ulnar shaft fractures 813.1 Distal Radius Fracture 813.42 Distal Ulna Fracture 813.82 Carpal Fracture 814.01 Metacarpal Fracture 815.0 Phalanx Fractures 816.0 Forearm/Wrist Fractures Radius fractures: • Radial head (may require a prosthesis) • Midshaft radius • Distal radius (most common) Residual deformities following radius fractures include: • Loss of radial tilt (Normal non fracture average is 22-23 degrees of radial tilt.) • Dorsal angulation (normal non fracture average palmar tilt 11-12 degrees.) • Radial shortening • Distal radioulnar (DRUJ) joint involvement • Intra-articular involvement with step-offs. Step-off of as little as 1-2 mm may increase the risk of post-traumatic arthritis. 1 Standard of Care: Distal Upper Extremity Fractures Copyright © 2007 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc. Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved. Types of distal radius fracture include: • Colle’s (Dinner Fork Deformity) -- Mechanism: fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH) with radial shortening, dorsal tilt of the distal fragment. The ulnar styloid may or may not be fractured. • Smith’s (Garden Spade Deformity) -- Mechanism: fall backward on a supinated, dorsiflexed wrist, the distal fragment displaces volarly. • Barton’s -- Mechanism: direct blow to the carpus or wrist. -

ISSN 2073 ISSN 2073 9990 East Cent. Afr. J. S

98 ISSN 20732073----99909990 East Cent. Afr. J. s urg Pisiform Dislocation and Distal Radius Ulna Fracture F.M. Kalande Department of Surgery, Ergerton University, Nakuru-Kenya. Email: [email protected] Background Pisiform dislocation is quite rare. In literature since the 40’s little discussion is documented about this. It is quite rare without other carpal bone dislocation. Pisiform dislocates when the wrist is forced into hypertension ;the flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU) tears of the pisiform and pisohamate ligament and or pisocarpitate ligament. Flexor Carpi ulnaris is a very powerful wrist flexor in extension the pisiform acts as a sesamoid bone enhancing its action. During such injury it is pulled in hypertension and displaces proximally or it may thereafter migrates distally. We report a rare condition where dislocation of pisiform is occurring not with carpal fractures or dislocation but with distal radius ulna fracture in a young skeletally immature boy, the treatment and outcome. Key words: pisiform, traumatic dislocation excision and radius/ulna fracture Case presentation We report a case of a 15-year old boy who presented with history of a fall while playing soccer at school. He sustained injury to his right wrist when he fell on an outreached hand, he developed immediate swelling and severe pain. On further evaluation there was tenderness over the wrist and the hypothenar eminence, and loss of range of motion due to pain. Neuronal assessment revealed normal function of the ulnar nerve . Operative AP View Pre-operative Lateral View. COSECSA/ASEA Publication ---East-East & Central African Journal of Surgery. Nov/Dec 2015 Vol. -

A Study on Management of Comminuted Colles Fracture by Closed Reduction and Ulnocarpal Stabilisation with 2 K-Wires

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences (IOSR-JDMS) e-ISSN: 2279-0853, p-ISSN: 2279-0861.Volume 14, Issue 4 Ver. IV (Apr. 2015), PP 45-51 www.iosrjournals.org A Study on Management of Comminuted Colles Fracture by Closed Reduction and Ulnocarpal Stabilisation with 2 K-Wires Dr. Addepalli Srinivasa Rao, M.S, M.ch (Ortho), Dr. K.N.Sandeep M.S(Ortho) Department of Orthopaedics, Siddhartha Medical College, Vijayawada, Andhrapradesh ,India 520008 Abstract Background – In comminuted Colles fractures treated by conventional method , malunion during healing due to progressive radial collapse is a common complication. Many modalities of treatment have been described with their merits and demerits. Ulnocarpal stabilization is an effective method to prevent radial collapse and hence this study. Materials And Methods – A prospective study of 100 patients of comminuted Colles fracture between 20-70 years age irrespective of sex treated by closed reduction and percutaneous stabilization of ulnocarpal articulation and above elbow POP cast for 6weeks has been presented. Patients were evaluated at 1 year follow up and functionally by Sarmiento’s modification of Lindstrom criteria and Gartland and Werley’s criteria. Results – Excellent to good results in 92%,fair in 4% and poor in 4% of total cases. Complications observed were malunion (n=6), pin tract infection (n=7), pullout of k-wire (n=5), sudeck’s osteodystrophy (n=7), residual pain (n=4),reduced grip strength (n=8) . Conclusion – Percutaneous pinnng by ulnocarpal stabilization is minimally invasive, yet an effective method to maintain the reduction and stability of distal radioulnar joint and radial collapse during healing ,even when the fracture is grossly comminuted ,intraarticular or unstable . -

Assessing Forearm Fractures from Eight Prehistoric California Populations

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research 2009 Assessing forearm fractures from eight prehistoric California populations Diane Marie DiGiuseppe San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation DiGiuseppe, Diane Marie, "Assessing forearm fractures from eight prehistoric California populations" (2009). Master's Theses. 3707. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.jm7h-xsgr https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/3707 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSESSING FOREARM FRACTURES FROM EIGHT PREHISTORIC CALIFORNIA POPULATIONS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Environmental Studies San Jose State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Diane Marie DiGiuseppe August 2009 UMI Number: 1478589 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dissertation Publishing UMI 1478589 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O.