Fracture Dislocations of the Proximal Interphalangeal Joint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

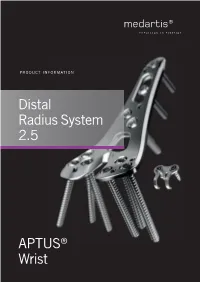

Distal Radius System 2.5

PRODUCT INFORMATION Distal Radius System 2.5 APTUS® Wrist 2 | Distal Radius System 2.5 Contents 3 A New Generation of Radius Plates 4 One System for Primary and Secondary Reconstruction 6 ADAPTIVE II Distal Radius Plates 8 FPL Plates 10 Hook Plates 11 Lunate Facet Plates 12 Rim Plates 13 Fracture Plates 14 Correction Plates 15 Volar Frame Plates 16 Extra-Articular Plates 17 Small Fragment Plates 18 Dorsal Frame Plates 19 XL Plates 20 Distal Ulna Plates 21 Fracture Treatment Concept 22 Technology, Biomechanics, Screw Features 24 Precisely Guided Screw Placement 25 Instrument for Reconstruction of the Volar Tilt 26 Storage 27 Overview Screw Trajectories 29 Ordering Information 47 Bibliography For further information regarding the APTUS product line visit: www.medartis.com Medartis, APTUS, MODUS, TriLock, HexaDrive and SpeedTip are registered trademarks of Medartis AG / Medartis Holding AG, 4057 Basel, Switzerland www.medartis.com Distal Radius System 2.5 | 3 A New Generation of Radius Plates Why is a new generation of radius plates needed? Distal radius fractures are the most common fractures of the stable plate systems have enabled open reduction and inter- upper extremities. The knowledge of these fractures has grown nal fixation to become an established treatment method for enormously over the last years. Treatment concepts have like- intra- and extra-articular distal radius fractures. These sys- wise been refined. It is now generally accepted that the best tems have enabled even severe extension fractures with dor- possible anatomical reconstruction of the radiocarpal joint sal defect zones to be precisely repositioned and treated with (RCJ) and distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) to produce a func- osteosynthesis via volar access without the need for additional tional outcome is a requirement. -

Series 1100TDM Tandem MEGALUG Mechanical Joint Restraint

Series 1100TDM Tandem MEGALUG® Mechanical Joint Restraint High Pressure Restraint for Ductile Iron Pipe Features and Applications: • For use on Ductile Iron Pipe 4 inch through 54 inch • High Pressure Restraint • Torque Limiting Twist-Off Nuts • Mechanical Joint follower gland incorporated into the restraint • MEGA-BOND® Coating System For more information on MEGA- BOND, visit our web site at www. ebaa.com • Minimum 2 to 1 Safety Factor Series 1112TDM restraining a mechanical joint fitting. • Constructed of A536 Ductile Iron Post Pressure Rating • EBAA-Seal™ Mechanical Nominal Pipe Shipping Assembly (PSI) Joint Gaskets are provided Size Weights* Deflection with all 1100TDM MEGALUG 4 21.6 3° 700 restraints. These are required 6 33.0 3° 700 to accommodate the pressure ratings and safety factors 8 40.0 3° 700 shown. 10 60.2 3° 700 12 75.0 3° 700 • New: High strength heavy hex 14 112.7 2° 700 machine bolts with T-nuts are 16 131.6 2° 700 provided to facilitate easier assembly due to the fittings 18 145.2 1½° 500 radius area prohibiting the use 20 166.6 1½° 500 longer T-bolts. 24 290.2 1½° 500 30 457.9 1° 500 • T-Nuts constructed of High 36 553.63 1° 500 Tensile Ductile Iron with Fluropolymer Coating. 42 1,074.8 1° 500 48 1,283.1 1° 500 For use on water or wastewater 54 1,445.32 ½° 400 pipelines subject to hydrostatic NOTE: For applications or pressures other than those shown please pressure and tested in accordance contact EBAA for assistance. -

2. Bilateral Cleft Anatomy 19

BILATERAL CLEFT ANATOMY IS ATTACHED TO THE SINGLE CLEFT THE PREMAXILLA NORMALLY ROTATED OUTWARD MAXILLA ON ONE SIDE AND THIS ENTIRE COMPONENT IS THE CLEFT SIDE MAXILLA IN AN VARYING DEGREES FROM ASYMMETRICAL DIFFERENT DISTORTION DOUBLE CLEFTS PRESENT AN ENTIRELY CONFIGURA TION IN THE COMPLETE BILATERAL CLEFT THE PREMAXILLA IS UNATTACHED THREE WHICH TO EITHER MAXILLA THUS THERE ARE SEPARATE COMPONENTS IN THEIR DISTORTION THE MAXILLAE ARE MORE OR LESS SYMMETRICAL TWO WHILE THE ARE USUALLY EQUAL TO EACH OTHER IN SIZE AND POSITION FORWARD ITS IN CENTRAL PREMAXILLARY ELEMENT PROCEEDS ON OWN WITHIN ITSELF FOR DIFFERENT DEGREES BUT WITH SYMMETRY EXCEPT IJI POSSIBLE DEVIATION FRONTONASAL THE COMPLETE SEPARATION OF THE CENTRAL COMPONENT OF PROLABIUM AND PREMAXILLA FROM THE LATERAL MAXILLARY SEGMENTS THE VASCULAR ABNORMALLY INFLUENCES NOSE PHILTRUM MUSCULATURE AND OF ALL THREE ELEMENTS ITY NERVE SUPPLY GROWTH DEVELOPMENT WHERE THE CLEFT IS INCOMPLETE ON BOTH SIDES THE DEFORMITY IS LESS AND IS STILL SYMMETRICAL IN SUCH CASE THERE IS USUALLY MORE OR LESS INTACT ALVEOLUS AND LITTLE OR NO PROTRUSION OF THE PRE THE MAXILLA THE COLUMELLA IS LIKELY TO BE LONGER THAN IN COMPLETE CLEFT BUT NOT OF NORMAL LENGTH SOMETIMES SOMETIMES THE DEGREE OF CLEFT VARIES ON EACH SIDE SIDE THE INCOMPLETENESS SHOWS AS ONLY THE SLIGHTEST NOTCH ON ONE SIDE OR THERE CLEFT ON THE OPPOSITE AND HALFWAY OR THREEQUARTER ON THE CLEFT ONE SIDE AND AN INCOMPLETE ONE CAN BE COMPLETE ON OF THE EXASPERATING ASPECT OTHER WHICH CONDITION EXAGGERATES THE ROTATION OF THE IN THE AND NOSE -

Tongue -Tie (Ankyloglossia) and Lip -Tie (Lip Adhesion)

Tongue -Tie (Ankyloglossia) and Lip -Tie (Lip Adhesion) What is Tongue-Tie? Most of us think of tongue -tie as a situation we find ourselves in when we are too excited to speak. Actually, tongue- tie is the non medical term for a relatively common physical condition that limits the use of the tongue, ankyloglossia. Lip -tie is a condition where the upper lip cannot be curled or moved normally. Before we are born, a strong cord of tissue that guides development of mouth structures is positioned in the center of the mouth. It is called a frenulum. As we develop, this frenulum recedes and thins. The lingual (tongue) or labial (lip) frenulum is visible and easily felt if you look in the mirror under your tongue and lip. In some children, the frenulum is especially tight or fails to recede and may cause tongue/lip mobility problems. The tongue and lip are a very complex group of muscles and are important for all oral function. For this reason having tongue tie can lead to nursing, eating, dental, or speech problems, which may be serious in some individuals. When Is Tongue and Lip- Tie a Problem That Needs Treatment? Infants A new baby with a too tight tongue and/or lip frenulum can have trouble sucking and may have poor weight gain. If they cannot make a good seal on the nipple, they may swallow air causing gas and stomach problems. Such feeding problems should be discussed with Dr. Sierra. Nursing mothers who experience significant pain while nursing or whose baby has trouble latching on should have their child evaluated for tongue and lip tie. -

Chapter 14. Anthropometry and Biomechanics

Table of contents 14 Anthropometry and biomechanics........................................................................................ 14-1 14.1 General application of anthropometric and biomechanic data .....................................14-2 14.1.1 User population......................................................................................................14-2 14.1.2 Using design limits ................................................................................................14-4 14.1.3 Avoiding pitfalls in applying anthropometric data ................................................14-6 14.1.4 Solving a complex sequence of design problems ..................................................14-7 14.1.5 Use of distribution and correlation data...............................................................14-11 14.2 Anthropometric variability factors..............................................................................14-13 14.3 Anthropometric and biomechanics data......................................................................14-13 14.3.1 Data usage............................................................................................................14-13 14.3.2 Static body characteristics....................................................................................14-14 14.3.3 Dynamic (mobile) body characteristics ...............................................................14-28 14.3.3.1 Range of whole body motion........................................................................14-28 -

Anthropometrical Orofacial Measurement in Children from Three to Five Years Old

899 MEDIDAS ANTROPOMÉTRICAS OROFACIAIS EM CRIANÇAS DE TRÊS A CINCO ANOS DE IDADE Anthropometrical orofacial measurement in children from three to five years old Raquel Bossle(1), Mônica Carminatti(1), Bárbara de Lavra-Pinto(1), Renata Franzon (2), Fernando de Borba Araújo (3), Erissandra Gomes(3) RESUMO Objetivo: obter as medidas antropométricas orofaciais em crianças pré-escolares de três a cinco anos e realizar a correlação com idade cronológica, gênero, raça e hábitos orais. Métodos: estudo transversal com 93 crianças selecionadas por meio de amostra de conveniência consecutiva. Os responsáveis responderam a um questionário sobre os hábitos orais e as crianças foram submetidas a uma avaliação odontológica e antropométrica da face. O nível de significância utilizado foi p<0,05. Resultados: as médias das medidas antropométricas orofaciais foram descritas. Houve diferença estatística nas medidas de altura da face (p<0,001), terço médio da face (p<0,001), canto externo do olho até a comissura labial esquerda/direita (p<0,001) e lábio inferior (p=0,015) nas faixas etárias. O gênero masculino apresentou medidas superiores na altura de face (p=0,003), terço inferior da face (p<0,001), lábio superior (p=0,001) e lábio inferior (p<0,001). Não houve diferença estatisticamente significante na altura do lábio superior em sujeitos não brancos (p=0,03). A presença de hábitos orais não influenciou os resultados. O aleitamento materno exclusivo por seis meses influenciou o aumento da medida de terço médio (p=0,022) e da altura da face (p=0,037). Conclusão: as médias descritas neste estudo foram superiores aos padrões encontrados em outros estudos. -

6.3.3 Distal Radius and Wrist

6 Specific fractures 6.3 Forearm and hand 6.3.3 Distal radius and wrist 1 Assessment 657 1.1 Biomechanics 657 1.2 Pathomechanics and classification 657 1.3 Imaging 658 1.4 Associated lesions 659 1.5 Decision making 659 2 Surgical anatomy 660 2.1 Anatomy 660 2.2 Radiographic anatomy 660 2.3 Preoperative planning 661 2.4 Surgical approaches 662 2.4.1 Dorsal approach 2.4.2 Palmar approach 3 Management and surgical treatment 665 3.1 Type A—extraarticular fractures 665 3.2 Type B—partial articular fractures 667 3.3 Type C—complete articular fractures 668 3.4 Ulnar column lesions 672 3.4.1 Ulnar styloid fractures 3.4.2 Ulnar head, neck, and distal shaft fractures 3.5 Postoperative care 674 3.6 Complications 676 3.7 Results 676 4 Bibliography 677 5 Acknowledgment 677 656 PFxM2_Section_6_I.indb 656 9/19/11 2:45:49 PM Authors Daniel A Rikli, Doug A Campbell 6.3.3 Distal radius and wrist of this stable pivot. The TFCC allows independent flexion/ 1 Assessment extension, radial/ulnar deviation, and pronation/supination of the wrist. It therefore plays a crucial role in the stability of 1.1 Biomechanics the carpus and forearm. Significant forces are transmitted across the ulnar column, especially while making a tight fist. The three-column concept (Fig 6.3.3-1) [1] is a helpful bio- mechanical model for understanding the pathomechanics of 1.2 Pathomechanics and classification wrist fractures. The radial column includes the radial styloid and scaphoid fossa, the intermediate column consists of the Virtually all types of distal radial fractures, with the exception lunate fossa and sigmoid notch (distal radioulnar joint, DRUJ), of dorsal rim avulsion fractures, can be produced by hyper- and the ulnar column comprises the distal ulna (DRUJ) with extension forces [2]. -

Medical Terminology Abbreviations Medical Terminology Abbreviations

34 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY ABBREVIATIONS MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY ABBREVIATIONS The following list contains some of the most common abbreviations found in medical records. Please note that in medical terminology, the capitalization of letters bears significance as to the meaning of certain terms, and is often used to distinguish terms with similar acronyms. @—at A & P—anatomy and physiology ab—abortion abd—abdominal ABG—arterial blood gas a.c.—before meals ac & cl—acetest and clinitest ACLS—advanced cardiac life support AD—right ear ADL—activities of daily living ad lib—as desired adm—admission afeb—afebrile, no fever AFB—acid-fast bacillus AKA—above the knee alb—albumin alt dieb—alternate days (every other day) am—morning AMA—against medical advice amal—amalgam amb—ambulate, walk AMI—acute myocardial infarction amt—amount ANS—automatic nervous system ant—anterior AOx3—alert and oriented to person, time, and place Ap—apical AP—apical pulse approx—approximately aq—aqueous ARDS—acute respiratory distress syndrome AS—left ear ASA—aspirin asap (ASAP)—as soon as possible as tol—as tolerated ATD—admission, transfer, discharge AU—both ears Ax—axillary BE—barium enema bid—twice a day bil, bilateral—both sides BK—below knee BKA—below the knee amputation bl—blood bl wk—blood work BLS—basic life support BM—bowel movement BOW—bag of waters B/P—blood pressure bpm—beats per minute BR—bed rest MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY ABBREVIATIONS 35 BRP—bathroom privileges BS—breath sounds BSI—body substance isolation BSO—bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy BUN—blood, urea, nitrogen -

About Your Knee

OrthoInfo Basics About Your Knee What are the parts of the knee? Your knee is Your knee is made up of four main things: bones, cartilage, ligaments, the largest joint and tendons. in your body Bones. Three bones meet to form your knee joint: your thighbone and one of the (femur), shinbone (tibia), and kneecap (patella). Your patella sits in most complex. front of the joint and provides some protection. It is also vital Articular cartilage. The ends of your thighbone and shinbone are covered with articular cartilage. This slippery substance to movement. helps your knee bones glide smoothly across each other as you bend or straighten your leg. Because you use it so Two wedge-shaped pieces of meniscal cartilage act as much, it is vulnerable to Meniscus. “shock absorbers” between your thighbone and shinbone. Different injury. Because it is made from articular cartilage, the meniscus is tough and rubbery to help up of so many parts, cushion and stabilize the joint. When people talk about torn cartilage many different things in the knee, they are usually referring to torn meniscus. can go wrong. Knee pain or injury Femur is one of the most (thighbone) common reasons people Patella (kneecap) see their doctors. Most knee problems can be prevented or treated with simple measures, such as exercise or Articular cartilage training programs. Other problems require surgery Meniscus to correct. Tibia (shinbone) 1 OrthoInfo Basics — About Your Knee What are ligaments and tendons? Ligaments and tendons connect your thighbone Collateral ligaments. These are found on to the bones in your lower leg. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

Sustentaculum Lunatum: Appreciation of the Palmar Lunate Facet in Management of Complex Intra-Articular Fractures of the Distal Radius

A Review Paper Sustentaculum Lunatum: Appreciation of the Palmar Lunate Facet in Management of Complex Intra-Articular Fractures of the Distal Radius Ebrahim Paryavi, MD, MPH, Matthew W. Christian, MD, W. Andrew Eglseder, MD, and Raymond A. Pensy, MD key role in restoring the anatomy of the palmar distal radial Abstract metaphysis during internal fixation. This fragment in com- Fracture of the distal radius is the most common wrist minuted fractures was first ascribed special importance by injury. Treatment of complex intra-articular fractures of Melone5 in his description of common fracture patterns. In the distal radius requires an accurate diagnosis of the the present article, we describe the anatomical characteristics fracture pattern and a thoughtful approach to fixation. of the sustentaculum lunatum and the clinical relevance of We propose a new term, sustentaculum lunatum, for this fragment to management of fractures of the distal radius. the palmar lunate facet. The sustentaculum lunatum deserves specific attention because of its importance Classification in load transmission across the radiocarpal joint. It is A variety of classification systems have been proposed to char- acterize and guide treatment of fractures of the distal radius. also key to restoring the anatomy of the palmarAJO distal The earliest descriptions of fracture patterns were presented by radial metaphysis during internal fixation. We provide Castaing6 and Frykman7 in the 1960s. The Frykman classifica- a review of the structure and function of the susten- tion historically has been popular but is limited in accuracy in taculum lunatum and describe fixation techniques. This its characterization of fragments and their displacement and is article is intended to promote awareness of this frag- limited in its ability to guide treatment. -

Head and Neck

DEFINITION OF ANATOMIC SITES WITHIN THE HEAD AND NECK adapted from the Summary Staging Guide 1977 published by the SEER Program, and the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual Fifth Edition published by the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging. Note: Not all sites in the lip, oral cavity, pharynx and salivary glands are listed below. All sites to which a Summary Stage scheme applies are listed at the begining of the scheme. ORAL CAVITY AND ORAL PHARYNX (in ICD-O-3 sequence) The oral cavity extends from the skin-vermilion junction of the lips to the junction of the hard and soft palate above and to the line of circumvallate papillae below. The oral pharynx (oropharynx) is that portion of the continuity of the pharynx extending from the plane of the inferior surface of the soft palate to the plane of the superior surface of the hyoid bone (or floor of the vallecula) and includes the base of tongue, inferior surface of the soft palate and the uvula, the anterior and posterior tonsillar pillars, the glossotonsillar sulci, the pharyngeal tonsils, and the lateral and posterior walls. The oral cavity and oral pharynx are divided into the following specific areas: LIPS (C00._; vermilion surface, mucosal lip, labial mucosa) upper and lower, form the upper and lower anterior wall of the oral cavity. They consist of an exposed surface of modified epider- mis beginning at the junction of the vermilion border with the skin and including only the vermilion surface or that portion of the lip that comes into contact with the opposing lip.