Mise En Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

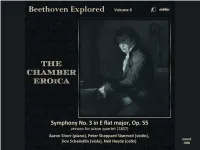

BEETHOVEN Explored Volume 6

BEETHOVEN Explored volume 6 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”) in E flat major, Op 55 (1803) Version for piano quartet, published Vienna, 1807 1 I Allegro con brio 18:18 2 II Marcia Funebre: Adagio assai 13:22 3 III Scherzo: Allegro vivace 6:13 4 IV Allegro molto 11:08 total CD duration 49:01 Peter Sheppard Skærved violin Dov Scheindlin viola Neil Heyde cello Aaron Shorr piano msvcd 2008 0809730008825 On the piano Quartet version of the Eroica Symphony - a player’s perspective Playing music written in the ‘pre-recording age’, I try to remember that, the predominant experience of orchestral and operatic music was in arrangement. Even with regular concert-going, people only had limited opportunities to hear any work. At the beginning of the 1800s, there was an enormous market of arrangements for home use, ranging from solo- violin transcriptions of melodies from operas, through works for chamber ensemble, ‘enlargements’ of piano works, re- instrumentations of other works, and reductions of orchestral pieces. An important ‘point of sale’ for much of this type of chamber music, was that it should function in a number of configurations. Duo transcriptions of opera arias were written so that they could be played by flutes or violins, and transcriptions involving piano usually functioned acceptably with all the ‘accompanying’ melody instruments missed out. It was in these versions that most people learnt the popular repertoire, playing or listening in the home or salon. It would be three decades into the 1800s before ‘full scores’ of orchestral pieces became available for study; Robert Schumann, writing in his 1841 ‘Marriage Diary’ with his new wife, Clara, spoke of his wish for a library of these for the two of them to work at together, playing the orchestra scores at the piano. -

Simply Beethoven

Simply Beethoven Simply Beethoven LEON PLANTINGA SIMPLY CHARLY NEW YORK Copyright © 2020 by Leon Plantinga Cover Illustration by José Ramos Cover Design by Scarlett Rugers All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, write to the publisher at the address below. [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-943657-64-3 Brought to you by http://simplycharly.com Contents Praise for Simply Beethoven vii Other Great Lives ix Series Editor's Foreword x Preface xi Introduction 1 1. The Beginning 5 2. Beethoven in Vienna: The First Years, 1792-1800 20 3. Into the New Century, 1800-05 38 4. Scaling the Heights, 1806-1809 58 5. Difficult Times, 1809-11 73 6. Distraction and Coping: 1812-15 91 7. 1816–1820: More Difficulties 109 8. Adversity and Triumph, 1821-24 124 9. Struggle and Culmination, 1825-1827 149 10. Beethoven’s Legacy 173 Sources 179 Suggested Reading 180 About the Author 182 A Word from the Publisher 183 Praise for Simply Beethoven “Simply Beethoven is a brief and eminently readable introduction to the life and works of the revered composer.Plantinga offers the lay- man reliable information based on his many years as a renowned scholar of the musical world of late-eighteenth and nineteenth- century Europe. -

Beethoven-Serie 03

Dr. Stephan Eisel An der Vogelweide 11 53229 Bonn [email protected] (17. Januar 2020) Stephan Eisel Die Musikstadt Bonn Die Musikliebhaberey nimmt unter den Einwohnern sehr zu“ – so charakterisierte das renommierte Magazin für Musik am 8. April 1787 Beethovens Heimatstadt, und ohne Zweifel wuchs der Komponist in einer ausgesprochenen Musikstadt auf. Das Zentrum bildeten die Hofkapelle und das Hoftheater, in dem die aktuellsten Opern der Zeit gespielt wurden. Darum herum hatte sich zugleich eine außerordentlich vielfältige Szene begabter Laienmusiker gebildet, zu denen auch der Kurfürst selbst gehörte. Als jüngster Sohn der Kaiserin Maria Theresia hatte Max Franz eine solide Musikausbildung erhalten, musizierte selbst vor allem an der Bratsche und nannte eine außergewöhnliche Notensammlung sein Eigen. Mit Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart war er persönlich bekannt und hatte auch die Möglichkeit ventiliert, diesen zum Bonner Hofkapellmeister zu berufen. Das Rückgrat der Musikstadt Bonn waren die örtlichen Musikerfamilien. Dass bei den Beethovens ab 1733 mit dem Bassisten und späteren Hofkapellmeister Ludwig van Beethoven d.Ä., seinem Sohn Johann (Tenor) und dem Enkel Ludwig drei Generationen aus einer Familie der Hofkapelle angehörten, war dabei keineswegs ungewöhnlich. Eine besonders einflussreiche Bonner Musiker-Dynastie war die Familie Ries. Johann Ries, gleichsam der „Urvater“ der Familie, war schon 1747 als Trompeter und ab 1754 als Geiger Mitglied in der Hofkapelle. Zwei seiner vier Kinder wurden ebenfalls Mitglieder des Orchesters: Johanns älteste Tochter Anna Maria (verheiratete Drewer) war 1764-1794 eine viel gelobte Sängerin, sein Sohn Franz Anton galt als Wunderkind und wurde 1774 offiziell als Geiger in die Hofkapelle aufgenommen, der er – in den 90er Jahren als Konzertmeister bzw. -

Vorwort Öffnen (PDF)

V Vorwort Clavier über einen Marsch in Mannheim eine Abschrift hergestellt wurde, die je- stechen lassen“ (Magazin der Musik, doch nicht überliefert ist. Von Gustav 2 Bde., Hamburg, 1783/84 und 1784/87; Nottebohm (Thematisches Verzeichnis Nachdruck, Hildesheim etc. 1971 – 74, der im Druck erschienenen Werke von Bd. 1, S. 394 f.). Die Originalausgabe Ludwig van Beethoven, Leipzig 21868, Die Beschäftigung mit Variationen für erschien 1782 bei Johann Michael Götz S. 157) noch als „revidirte Abschrift“ Klavier umspannt im Leben Ludwig in Mannheim mit dem Titel „Varia- bezeichnet, wurde die Handschrift auch van Beethovens (1770 – 1827) einen tions pour le clavecin sur une marche de im Katalog Nr. 59 von L. Liepmanns- Zeitraum von mehr als 40 Jahren und Mr Dressler“; der genannte Marsch von sohn, Berlin, für die Versteigerung am somit beinahe sein gesamtes Wirken als Ernst Christoph Dressler (1734 – 79) ist 20. und 21. Mai 1930 (unter Nr. 15) als Komponist. Sie beginnt bei ihm im Al- nicht überliefert. In den späteren Auf- „Musikmanuskript von Kopistenhand ter von etwa 12 Jahren mit seinem ers- lagen ist der Name Dressler nicht mehr mit eigenhändigem Titel“ und „eigen- ten veröffentlichten Werk überhaupt genannt (siehe die 2. Fassung in Bd. II händigen Korrekturen“ angeführt. Bei (WoO 63, 1782), reicht über Gelegen- der Variationen für Klavier, HN 1269). dieser Auktion erwarb Hans Conrad heitswerke seiner frühen Jahre und die Angezeigt wurde die Originalausgabe Bodmer das Manuskript, das sich bei in „ganz neuer Manier“ geschriebenen erst in Götz’ Verlagskatalog des Jahres einer früheren genaueren Untersuchung Variationen op. 34 und 35 bis zu den 1784 (vgl. -

The Influence of Ancient Esoteric Thought Through

THROUGH THE LENS OF FREEMASONRY: THE INFLUENCE OF ANCIENT ESOTERIC THOUGHT ON BEETHOVEN’S LATE WORKS BY BRIAN S. GAONA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Clinical Assistant Professor/Artist in Residence Brandon Vamos, Chair Professor William Kinderman, Director of Research Associate Professor Donna A. Buchanan Associate Professor Zack D. Browning ii ABSTRACT Scholarship on Ludwig van Beethoven has long addressed the composer’s affiliations with Freemasonry and other secret societies in an attempt to shed new light on his biography and works. Though Beethoven’s official membership remains unconfirmed, an examination of current scholarship and primary sources indicates a more ubiquitous Masonic presence in the composer’s life than is usually acknowledged. Whereas Mozart’s and Haydn’s Masonic status is well-known, Beethoven came of age at the historical moment when such secret societies began to be suppressed by the Habsburgs, and his Masonic associations are therefore much less transparent. Nevertheless, these connections surface through evidence such as letters, marginal notes, his Tagebuch, conversation books, books discovered in his personal library, and personal accounts from various acquaintances. This element in Beethoven’s life comes into greater relief when considered in its historical context. The “new path” in his art, as Beethoven himself called it, was bound up not only with his crisis over his incurable deafness, but with a dramatic shift in the development of social attitudes toward art and the artist. -

A Study of Js Bach's Toccata Bwv 916; L. Van Beethoven's Sonata

A STUDY OF J. S. BACH’S TOCCATA BWV 916; L. VAN BEETHOVEN’S SONATA OP. 31, NO. 3; F. CHOPIN’S BALLADE, OP. 52; L. JANÁČEK’S IN THE MISTS: I, III; AND S. PROKOFIEV’S SONATA, OP. 28: HISTORICAL, THEORETICAL, STYLISTIC AND PEDAGOGICAL IMPLICATIONS by JANA KRAJČIOVÁ B.M., Northwestern State University of Louisiana, 2010 A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC Department of Music College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2012 Approved by: Major Professor: Dr. Sławomir P. Dobrzański Abstract The following report analyzes compositions performed at the author’s Master’s Piano Recital on March 15, 2012. The discussed pieces are Johann Sebastian Bach’s Toccata in G major, BWV 916; Ludwig van Beethoven’s Sonata in E flat major, op. 31, No. 3; Frederic Chopin’s Ballade in F minor, op. 52; Leoš Janáček’s In The Mists: I. Andante, III. Andantino; and Sergei Prokofiev’s Sonata in A minor, op. 28. The author approaches the study from the historical, theoretical, stylistic and pedagogical perspectives. Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ vi List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. ix Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................... x Preface........................................................................................................................................... -

Ries-Journal 18 2Ling Iast.Indd

Ausgabe 5 | 2018 RIES JOURNAL Der Wiener Klavierbauer Joseph Franz Ries (1792-1861) Sein Leben, seine Patente und seine Instrumente C. A. Hainholz cpo Biographische Notizen Höchst Originelles und Dramatisches von Ferdinand Ries über Ludwig van Beethoven Ferdinand von Dr. F.G. Wegeler und Ferdinand Ries Neu! Ries Herausgegeben von der Ferdinand Ries Gesellschaft in Zusammenarbeit mit der Julius Wegeler Familienstiftung und dem Landschaftsverband Rheinland Mit einem Vorwort von Michael Ladenburger cpo Leinengebundene Ausgabe in 777 767–2 einer nummerierten Aufl age von »Ferdinand Ries, dieser ungeheuer fleißige 300 Exemplaren. Mann tritt dank einer sehr ernsthaften, inni- gen Auseinandersetzung mit seiner letzten Bibliophile Ausstattung mit Lese- Geigensonate aus dem selbstgeschaffenen bändchen und faksimilierten Brief- Schatten heraus, um sich zeitweilig in gera- und Notenbeispielen Ludwig van Beet- dezu bekenntnishafte Höhen zu erheben.« hovens. 232 Seiten, Bonn 2012 klassik-heute. com 28 € (zzgl. Porto und Versand) Zu erwerben bei: Ferdinand Ries Gesellschaft, Kaufmannstr. 32, D – 53115 Bonn [email protected] ISBN: 978-3-00-039547-5 cpo 777 216–2 cpo 777 609–2 cpo 777 738–2 cpo 777 655–2 4 CDs CD SACD/Hybrid 2 CDs „Das Buch wird viel gelesen werden, wie es dies verdient ... Man kann nicht los davon.“ CD-Bestellung gegen Rechnung unter: jpc.de | jpc-Schallplatten-Versandhandelsgesellschaft mbH | Georgsmarienhütte Robert Schumann Geschäftsführer: Gerhard Georg Ortmann | Amtsgericht Osnabrück HRB 110327 Internationaler Vertrieb: A: Preiser Records, NL: Econa | cpo gibt’s auch im Internet: www.cpo.de 04-2016 Ries-Anzeige.indd 1 22.03.2016 15:37:38 RIES JOURNAL 5 Inhalt Content 2 2 Editorial Editorial 3 3 Vorbemerkung der Redaktion Editor’s Preliminary Remarks 7 7 Sabine K. -

DETERMINING the AUTHENTICITY of the CONCERTO for TWO HORNS, Woo. 19, ATTRIBUTED to FERDINAND RIES

DETERMINING THE AUTHENTICITY OF THE CONCERTO FOR TWO HORNS, WoO. 19, ATTRIBUTED TO FERDINAND RIES Amy D. Laursen, B.M.E., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2015 APPROVED: William Scharnberg, Major Professor Kris Chesky, Related Field Professor Brian Bowman, Committee Member Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies, College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Laursen, Amy D. Determining the Authenticity of the Concerto for Two Horns, WoO. 19, Attributed to Ferdinand Ries. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), December 2015, 100 pp., 1 table, 27 figures, 57 musical examples, references, 108 titles. Ferdinand Ries is credited as the composer of the Concerto for Two Horns, WoO. 19 preserved in the Berlin State Library. Dated 1811, ostensibly Ries wrote it in the same year as his Horn Sonata, Op. 34, yet the writing for the horns in the Concerto is significantly more demanding. Furthermore, Ries added to the mystery by not claiming the Concerto in his personal catalog of works or mentioning it in any surviving correspondence. The purpose of this dissertation is to study the authorship of the Concerto for Two Horns and offer possible explanations for the variance in horn writing. Biographical information of Ries is given followed by a stylistic analysis of Ries’s known works. A stylistic analysis of the Concerto for Two Horns, WoO. 19 is offered, including a handwriting comparison between the Concerto for Two Horns and Ries’s Horn Sonata. Finally, possible explanations are proposed that rationalize the variance in horn writing between the Concerto for Two Horns, WoO. -

Essays on the Main Themes of BTHVN2020

Essays on the Main Themes of BTHVN2020 B Beethoven as a Bonn-born cosmopolitan Ludwig van Beethoven, whose 250th birthday we will celebrate in 2020, was born in December 1770 in the building known today as the Beethoven-Haus. He was baptised on 17 December in the Church of St Remigius (no longer extant) on Bonn’s Remigiusplatz (Remigius Square). The day of his baptism appears in the parish register, but the day of his birth is unknown. It was probably 16 December 1770. The boy Beethoven grew up in the stimulating surroundings of a musical family. His grandfather Louis (1712–1773) was born in Mechelen in present-day Belgium (the town formed part of the Austrian Netherlands in the 18th century). He became a singer at the court of the Elector of Cologne in 1733 and made his career in the court chapel. In 1761 Elector Maximilian Friedrich even appointed him Hofkapellmeister, making him the head of music at his court. His son Johann – Ludwig’s father – was likewise a tenor in the court chapel, as was Ludwig himself later, first as deputy organist and from 1789 as a viola player. He presumably received his first wages at the early age of 13. By then he had already dedicated three piano sonatas to Maximilian Friedrich, the so-called ‘Kürfürstensonaten’. This was a great honour, considering that a dedication had to be accepted by the dedicatee, and a decisive step toward Ludwig’s establishment in the flourishing musical scene of his native city. There is still much to learn about the Bonn court chapel. -

SWR2 Musikstunde

SWR2 MANUSKRIPT SWR2 Musikstunde Das Verlagshaus Simrock Vom Wein- und Musikalienhandel zum Global Player (1) Mit Jan Ritterstaedt Sendung: Montag, 03. April 2017 Redaktion: Bettina Winkler Produktion: SWR 2017 Bitte beachten Sie: Das Manuskript ist ausschließlich zum persönlichen, privaten Gebrauch bestimmt. Jede weitere Vervielfältigung und Verbreitung bedarf der ausdrücklichen Genehmigung des Urhebers bzw. des SWR. Service: SWR2 Musikstunde können Sie auch als Live-Stream hören im SWR2 Webradio unter www.swr2.de Kennen Sie schon das Serviceangebot des Kulturradios SWR2? Mit der kostenlosen SWR2 Kulturkarte können Sie zu ermäßigten Eintrittspreisen Veranstaltungen des SWR2 und seiner vielen Kulturpartner im Sendegebiet besuchen. Mit dem Infoheft SWR2 Kulturservice sind Sie stets über SWR2 und die zahlreichen Veranstaltungen im SWR2-Kulturpartner-Netz informiert. Jetzt anmelden unter 07221/300 200 oder swr2.de SWR2 Musikstunde vom 03.04. bis 07.04.2017 Montag, 03. April 2017 Mit Jan Ritterstaedt Das Verlagshaus Simrock Vom Wein- und Musikalienhandel zum Global Player (1) Signet Dazu begrüßt sie Jan Ritterstaedt. In dieser Woche werfen wir mal einen Blick auf die Geschichte eines Musikverlages, der eine ganz bedeutende Rolle für die Musikgeschichte gespielt hat: Wir erkunden den Aufstieg und Fall des Verlagshauses Simrock. Und zu Beginn unserer Serie knüpfen wir uns zunächst einmal dessen Gründervater Nikolaus Simrock vor. Indikativ Wir sehen einen alten Mann - so um die 70 Jahre dürfte er schon auf dem Buckel haben. Ernst ist sein Gesichtsausdruck, ein wenig bleich wirkt seine Hautfarbe und über dem Kopf trägt er eine weiße Zipfelmütze. Das ist die Beschreibung des einzigen Portraits, was wir von Nikolaus Simrock haben. Es wird heute im Bonner Stadtmuseum aufbewahrt und stammt vermutlich von Karl Stieler, dem Maler, der auch ein berühmtes Portrait Ludwig van Beethovens angefertigt hat. -

Arnold Story V3 for Internet

A biography of Friedrich Wilhelm Arnold (1810-1864) A life imbued with music Peter Van Leeuwen 2018 A biography of Friedrich Wilhelm Arnold (1810-1864): A life imbued with music. (V.1805E_I) www.van-leeuwen.de Copyright © Peter Van Leeuwen 2018 All rights reserved Front Cover: Excerpt from one of Arnold's compositions: Allegro , published in: Pfennig- Magazin für Gesang und Guitarre. Herausgegeben von einem Verein Rheinländischer Tonkünstler. Redigirt von F.W. Arnold . Cologne, Gaul & Tonger. 1835 1(4): 190. Back Cover: Reproduction of a photograph of the portrait of Friedrich Wilhelm Arnold. 3 Table of contents Table of contents .................................................................................... 3 Preface .................................................................................................... 7 Origins ..................................................................................................... 9 Childhood and Schooling ....................................................................... 13 Student days ......................................................................................... 16 Cologne, London, Aachen: Journalism, Music, Theater ......................... 20 Novelist ................................................................................................. 24 The Music Business, Part I: Cologne ...................................................... 29 Marriage ............................................................................................... 30 Musical Pursuits: -

The Manuscript Transmission of Js

THE MANUSCRIPT TRANSMISSION OF J. S. BACH’S MASS IN B MINOR (BWV 232) AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONCEPT OF TEXTUAL AUTHORITY, 1750-1850 by DANIEL FELLERS BOOMHOWER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2017 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Daniel Fellers Boomhower candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.* Committee Chair Susan McClary Committee Member L. Peter Bennett Committee Member Francesca Brittan Committee Member Martha Woodmansee Date of Defense January 26, 2017 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. For Keely, Eleanor, and Greta Table of Contents List of Tables v List of Figures vi Bibliographic Abbreviations vii Acknowledgements viii Abstract x Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Composing 16 Chapter 2: Revising 51 Chapter 3: Copying 84 Chapter 4: Collecting 114 Chapter 5: Performing 148 Chapter 6: Editing 182 Conclusion 212 Bibliography 218 iv List of Tables Table 2.1: Stages of Revisions by C. P. E. Bach to the Mass in B Minor 68 Table 5.1: Performances of the Mass in B Minor, 1770s-1850s 152 v List of Figures Figure 1.1: Parody Sources for the “Lutheran” Masses (BWV 233-236) 32 Figure 2.1: Stage I Revisions to the Symbolum Nicenum 68 Figure 2.2: C. P. E. Bach’s Insertions into the Autograph 69 Figure 2.3: Stemma of Revision Stages I and II 70 Figure 2.4: Stage III Revisions to the