Essays on the Main Themes of BTHVN2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elaine Fitz Gibbon

Elaine Fitz Gibbon »Beethoven und Goethe blieben die Embleme des kunstliebenden Deutschlands, für jede politische Richtung unantastbar und ebenso als Chiffren manipulierbar« (Klüppelholz 2001, 25-26). “Beethoven and Goethe remained the emblems of art-loving Germany: untouchable for every political persuasion, and likewise, as ciphers, just as easily manipulated.”1 The year 2020 brought with it much more than collective attempts to process what we thought were the uniquely tumultuous 2010s. In addition to causing the deaths of over two million people worldwide, the Covid-19 pandemic has further exposed the extraordinary inequities of U.S.-American society, forcing a long- overdue reckoning with the entrenched racism that suffuses every aspect of American life. Within the realm of classical music, institutions have begun conversations about the ways in which BIPOC, and in particular Black Americans, have been systematically excluded as performers, audience members, administrators and composers: a stark contrast with the manner in which 2020 was anticipated by those same institutions before the pandemic began. Prior to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, they looked to 2020 with eager anticipation, provoking a flurry of activity around a singular individual: Ludwig van Beethoven. For on December 16th of that year, Beethoven turned 250. The banners went up early. In 2019 on Instagram, Beethoven accounts like @bthvn_2020, the “official account of the Beethoven Anniversary Year,” sprang up. The Twitter hashtags #beethoven2020 and #beethoven250 were (more or less) trending. Prior to the spread of the virus, passengers flying in and out of Chicago’s O’Hare airport found themselves confronted with a huge banner that featured an iconic image of Beethoven’s brooding face, an advertisement for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s upcoming complete cycle Current Musicology 107 (Fall 2020) ©2020 Fitz Gibbon. -

5 Music Cruises 2019 E.Pub

“The music is not in the notes, but in the silence between.” Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart RHINE 2019 DUDOK QUARTET Aer compleng their studies with disncon at the Dutch String Quartet Academy in 20 3, the Quartet started to have success at internaonal compeons and to be recognized as one of the most promising young European string quartets of the year. In 20 4, they were awarded the Kersjes ,rize for their e-ceponal talent in the Dutch chamber music scene. .he Quartet was also laureate and winner of two special prizes during the 7th Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 3 1 2ordeau- and won st place at both the st Internaonal String Quartet 0ompeon 20 in 3adom 4,oland5 and the 27th 0harles 6ennen Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompe7 on 20 2. In 20 2, they received 2nd place at the 8th 9oseph 9oachim Internaonal 0hamber Music 0ompeon in Weimar 4:ermany5. .he members of the quartet ;rst met in the Dutch street sym7 phony orchestra “3iccio=”. From 2009 unl 20 , they stu7 died with the Alban 2erg Quartet at the School of Music in 0ologne, then to study with Marc Danel at the Dutch String Quartet Academy. During the same period, the quartet was coached intensively by Eberhard Feltz, ,eter 0ropper 4Aindsay Quartet5, Auc7Marie Aguera 4Quatuor BsaCe5 and Stefan Metz. Many well7Dnown contemporary classical composers such as Kaija Saariaho, MarD7Anthony .urnage, 0alliope .sou7 paDi and Ma- Knigge also worDed with the quartet. In 20 4, the Quartet signed on for several recordings with 3esonus 0lassics, the worldEs ;rst solely digital classical music label. -

Schubert's!Voice!In!The!Symphonies!

! ! ! ! A!Search!for!Schubert’s!Voice!in!the!Symphonies! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Camille!Anne!Ramos9Klee! ! Submitted!to!the!Department!of!Music!of!Amherst!College!in!partial!fulfillment! of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of!Bachelor!of!Arts!with!honors! ! Faculty!Advisor:!Klara!Moricz! April!16,!2012! ! ! ! ! ! In!Memory!of!Walter!“Doc”!Daniel!Marino!(191291999),! for!sharing!your!love!of!music!with!me!in!my!early!years!and!always!treating!me!like! one!of!your!own!grandchildren! ! ! ! ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! ! Introduction! Schubert,!Beethoven,!and!the!World!of!the!Sonata!! 2! ! ! ! Chapter!One! Student!Works! 10! ! ! ! Chapter!Two! The!Transitional!Symphonies! 37! ! ! ! Chapter!Three! Mature!Works! 63! ! ! ! Bibliography! 87! ! ! Acknowledgements! ! ! First!and!foremost!I!would!like!to!eXpress!my!immense!gratitude!to!my!advisor,! Klara!Moricz.!This!thesis!would!not!have!been!possible!without!your!patience!and! careful!guidance.!Your!support!has!allowed!me!to!become!a!better!writer,!and!I!am! forever!grateful.! To!the!professors!and!instructors!I!have!studied!with!during!my!years!at! Amherst:!Alison!Hale,!Graham!Hunt,!Jenny!Kallick,!Karen!Rosenak,!David!Schneider,! Mark!Swanson,!and!Eric!Wubbels.!The!lessons!I!have!learned!from!all!of!you!have! helped!shape!this!thesis.!Thank!you!for!giving!me!a!thorough!music!education!in!my! four!years!here!at!Amherst.! To!the!rest!of!the!Music!Department:!Thank!you!for!creating!a!warm,!open! environment!in!which!I!have!grown!as!both!a!student!and!musician.!! To!the!staff!of!the!Music!Library!at!the!University!of!Minnesota:!Thank!you!for! -

Haydn London Symphony

Portrait of Franz Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1791 WHAT MAKES IT GREAT?® HAYDN LONDON SYMPHONY 20 CONCERT PROGRAM Louis Babin Friday, February 10, 2017 Retrouvailles: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th* 7:30pm (TSO PREMIÈRE/TSO CO-COMMISSION) Rob Kapilow Rob Kapilow What Makes It Great?® conductor & host Haydn London Symphony Gary Kulesha* conductor Intermission Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 104 in D Major “London” I. Adagio – Allegro II. Andante III. Menuet: Allegro IV. Allegro spiritoso Audience Q&A with Rob Kapilow and Orchestra Please note that Louis Babin’s Retrouvailles is being recorded for online release at TSO.CA/CanadaMosaic. Tonight’s What Makes It Great?® program is all about listening. Paying attention. Noticing all the fantastic things in great music that race by at lightning speed, note by note, and measure by measure. Listening to a piece of music from the composer’s point of view—from the inside out. During the first half of the concert, we will look at selected passages from Franz Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 104 (“London”) and I will do everything in my power to get you inside the piece to Rob Kapilow hear what makes it tick and what makes it great. Then, after intermission, we will conductor perform the piece in its entirety, and you will hopefully listen to it with a whole & host new pair of ears. I am thrilled to be sharing this great music with you tonight. All you have to do is listen. 21 For a program note to Louis Babin’s Retrouvailles: Sesquie THE DETAILS for Canada’s 150th, please turn to pg. -

8.573726 Ries Booklet.Pdf

573726 bk Ries EU.qxp_573726 bk Ries EU 28/03/2018 11:31 Page 2 Ferdinand Ries (1784–1838) Stefan Stroissnig Cello Sonatas The Austrian pianist Stefan Stroissnig (b. 1985), studied in Vienna and at Ferdinand Ries was baptised in Bonn on 28 November cello concerto. Ries’s dedication of these two works to the Royal College of Music in London. His concert activity as a soloist 1784. Today his name is rarely mentioned without a Bernhard Romberg, from whom he also received cello has taken him around the world and to the most important concert reference to Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827), even if lessons, might have been an attempt to use the famous houses in Europe. He is recognised for his interpretations of works by it is likely that it was only after his arrival in Vienna on 29 name to gain attention. Ries had done the same in the Schubert and for 20th- and 21st-century repertoire. He has performed December 1802 that Ries had significant contact with dedication of his Piano Sonatas, Op. 1 to Beethoven, where works by Olivier Messiaen, Friedrich Cerha, Claude Vivier, Morton Beethoven. Ries’ father, Franz Anton Ries (1755–1846) he claimed to be Beethoven’s ‘sole student’ and ‘friend’. Feldman, Ernst Krenek as well as piano concertos by John Cage and was the archbishopric concertmaster and one of However, Ries and Romberg ended up performing Pascal Dusapin. He is a regular guest at many prominent festivals, and Beethoven’s teachers, before Beethoven left for Vienna in the Cello Sonatas, Op. 20 and Op. -

Scuola Pianistica Milanese»

Guido Salvetti Forse non ci fu una «scuola pianistica milanese» Una valutazione del ruolo del pianoforte nella vita musicale milanese del primo Ottocen- to deve dar ragione di aspetti non poco contraddittori. Da un lato appare chiaro il ruolo secondario del pianoforte nelle istituzioni pubbliche di istruzione e di concerto. Dall’al- tro appare imponente l’attività che potremmo dire privata, quale ci viene testimoniata dai ‹nobili dilettanti› e dai cataloghi editoriali. Osserviamo innanzi tutto alcuni dati recentemente raccolti sulle pubbliche accade- mie del Regio Conservatorio, a partire dalla sua fondazione nel 1808.1 Pur tenendo conto delle inevitabili lacune di uno spoglio d’archivio, appaiono clamorose le assenze di esi- bizioni pianistiche per interi anni, sommerse da un enorme numero di brani operistici e di ariette. Nei primi dieci anni di vita dell’istituzione, l’insegnante Benedetto Negri propone alle autorità e al pubblico cittadino soltanto questi due interventi pianistici: 8 ottobre 18122 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Variazioni per clavicembalo Giovanni Battista Rabitti3 1 ottobre 18154 Friedrich Heinrich Himmel Sonata per pianoforte5 [Luigi] Rabitti «minore» con accompagnamento di corni da caccia: Giacomo Belloli e Giuseppe Schiroli 1 Milano e il suo Conservatorio, a c. di Guido Salvetti, Milano 2003; cd-rom allegato, Appendice iv: Cronologia dei saggi degli allievi dal 1809 al 1896. Questa è l’avvertenza iniziale: «Per la compilazione della cronologia sono stati consultati i programmi di sala e, in alternativa, le recensioni apparse sulla Gazzetta musicale di Milano e sulla Perseveranza. In generale, per i titoli si è mantenuta la grafia come appare nel documento originale; dove è stato possibile si è provveduto, invece, a completare i nomi degliallieviedegliautori». -

Sinfonie Inedite Sinfonie

THE UNPUBLISHED SYMPHONIES UNPUBLISHED THE SINFONIE INEDITE SINFONIE Fondazione Benefica Kathleen Foreman Casali, Fondazione De Claricini Dornpacher Claricini De Fondazione Casali, Foreman Kathleen Benefica Fondazione Fondazione Ada e Antonio Giacomini, Fondazione CRTrieste, CRTrieste, Fondazione Giacomini, Antonio e Ada Fondazione Provincia di Trieste, Comune di Trieste – Museo Revoltella, Revoltella, Museo – Trieste di Comune Trieste, di Provincia Con il sostegno di: sostegno il Con who have supported in this effort. this in supported have who Very grateful to Federica Galli Foundation and to Lorenza Salamon, Salamon, Lorenza to and Foundation Galli Federica to grateful Very Motta di Livenza, 1741 - Bonn, 1801 Bonn, - 1741 Livenza, di Motta che ci hanno aiutato in questa iniziativa. questa in aiutato hanno ci che Grazie alla Fondazione Federica Galli e a Lorenza Salamon, Lorenza a e Galli Federica Fondazione alla Grazie Studio Bertin, Milan Bertin, Studio project: Graphic Jean Suzanne Chaloux Suzanne Jean by: Translated Bruno Belli Bruno notes: Booklet Bacino di San Marco, 1984/85 (Courtesy Salamon Gallery, Milan) Gallery, Salamon (Courtesy 1984/85 Marco, San di Bacino Federica Galli, Venezia, Venezia, Galli, Federica image: Cover Gattuso Claudio and Caldara Federico engineer: sound and Recording 2014 2014 7 , 6 January recording: of Date th th Bottenicco di Moimacco (Cividale del Friuli) Friuli) del (Cividale Moimacco di Bottenicco Villa De Claricini, De Villa at: Recorded Production for Concerto: Concerto: for Production Andrea Maria -

Christian Gottlob Neefe and the Early Reception of Le Nozze Di Figaro and Don Giovanni

Christian Gottlob Neefe and the Early Reception of Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni Woodfield, I. (2016). Christian Gottlob Neefe and the Early Reception of Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni. Newsletter of the Mozart Society of America, 20(1), 4-6. Published in: Newsletter of the Mozart Society of America Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights © 2016 The Newsletter of the Mozart Society of America General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:27. Sep. 2021 Christian Gottlob Neefe and the early reception of Figaro and Don Giovanni When he became Elector of Bonn in 1784, Joseph II’s youngest brother, the music-loving Maximilian Franz, inherited a financial crisis as a result of which he had to close the stage.1 During the five-year theatrical hiatus that ensued, Bonn missed out on public productions of the new wave of popular Viennese operas by Salieri, Martín y Soler, Mozart and Dittersdorf. -

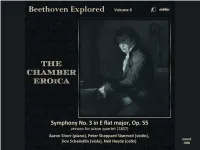

BEETHOVEN Explored Volume 6

BEETHOVEN Explored volume 6 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”) in E flat major, Op 55 (1803) Version for piano quartet, published Vienna, 1807 1 I Allegro con brio 18:18 2 II Marcia Funebre: Adagio assai 13:22 3 III Scherzo: Allegro vivace 6:13 4 IV Allegro molto 11:08 total CD duration 49:01 Peter Sheppard Skærved violin Dov Scheindlin viola Neil Heyde cello Aaron Shorr piano msvcd 2008 0809730008825 On the piano Quartet version of the Eroica Symphony - a player’s perspective Playing music written in the ‘pre-recording age’, I try to remember that, the predominant experience of orchestral and operatic music was in arrangement. Even with regular concert-going, people only had limited opportunities to hear any work. At the beginning of the 1800s, there was an enormous market of arrangements for home use, ranging from solo- violin transcriptions of melodies from operas, through works for chamber ensemble, ‘enlargements’ of piano works, re- instrumentations of other works, and reductions of orchestral pieces. An important ‘point of sale’ for much of this type of chamber music, was that it should function in a number of configurations. Duo transcriptions of opera arias were written so that they could be played by flutes or violins, and transcriptions involving piano usually functioned acceptably with all the ‘accompanying’ melody instruments missed out. It was in these versions that most people learnt the popular repertoire, playing or listening in the home or salon. It would be three decades into the 1800s before ‘full scores’ of orchestral pieces became available for study; Robert Schumann, writing in his 1841 ‘Marriage Diary’ with his new wife, Clara, spoke of his wish for a library of these for the two of them to work at together, playing the orchestra scores at the piano. -

Revisiting Zero Hour 1945

REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER VOLUME 1 American Institute for Contemporary German Studies The Johns Hopkins University REVISITING ZERO-HOUR 1945 THE EMERGENCE OF POSTWAR GERMAN CULTURE edited by STEPHEN BROCKMANN FRANK TROMMLER HUMANITIES PROGRAM REPORT VOLUME 1 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies. ©1996 by the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies ISBN 0-941441-15-1 This Humanities Program Volume is made possible by the Harry & Helen Gray Humanities Program. Additional copies are available for $5.00 to cover postage and handling from the American Institute for Contemporary German Studies, Suite 420, 1400 16th Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20036-2217. Telephone 202/332-9312, Fax 202/265- 9531, E-mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.aicgs.org ii F O R E W O R D Since its inception, AICGS has incorporated the study of German literature and culture as a part of its mandate to help provide a comprehensive understanding of contemporary Germany. The nature of Germany’s past and present requires nothing less than an interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of German society and culture. Within its research and public affairs programs, the analysis of Germany’s intellectual and cultural traditions and debates has always been central to the Institute’s work. At the time the Berlin Wall was about to fall, the Institute was awarded a major grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to help create an endowment for its humanities programs. -

Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2017 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2017 Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone Aaron Mumford Boehlert Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017 Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Boehlert, Aaron Mumford, "Hitler's Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone" (2017). Senior Projects Spring 2017. 136. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2017/136 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hitler’s Germania: Propaganda Writ in Stone Senior Project submitted to the Division of Arts of Bard College By Aaron Boehlert Annandale-on-Hudson, NY 2017 A. Boehlert 2 Acknowledgments This project would not have been possible without the infinite patience, support, and guidance of my advisor, Olga Touloumi, truly a force to be reckoned with in the best possible way. We’ve had laughs, fights, and some of the most incredible moments of collaboration, and I can’t imagine having spent this year working with anyone else. -

Kat.%2010.Pdf

Musikantiquariat Marion Neugebauer Am Weidenbach 16 82347 Bernried +49 8158 90 39 59 [email protected] www.musikantiquariat-neugebauer.de Für die Echtheit der angebotenen Drucke und Handschriften wird garantiert Mitglied im Verband deutscher Antiquare e. V. und in der International League of Antiquarian Booksellers (ILAB) Geschäftsbedingungen: Es gelten die in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland wirksamen gesetzlichen Bestimmungen. Das Angebot ist freibleibend. Lieferzwang besteht nicht. Mit Aufgabe einer Bestellung werden die Geschäftsbedingungen anerkannt. Die Preise verstehen sich in Euro inklusive der bei Lieferung gültigen Mehrwertsteuer, soweit nicht § 25a UStG angewandt wird. Sie erhalten eine Rechnung mit ausgewiesener Mehrwertsteuer, soweit nicht § 25a UStG angewandt wird. Erfüllungsort und Gerichtsstand für beide Teile ist Bernried am Starnberger See. Eigentumsvorbehalt nach § 449 BGB bis zur vollständigen Bezahlung. Meine Rechnungen sind zahlbar ohne Abzüge nach Empfang. Der Versand erfolgt auf Kosten und Gefahr des Bestellers. Die angebotenen Objekte befinden sich in gutem Zustand, soweit nicht anders beschrieben. Unwesentliche Mängel (wie z.B. Namenseintrag) werden nicht immer erwähnt, sondern im Preis berücksichtigt. Begründete Reklamationen bitte ich innerhalb von 14 Tagen geltend zu machen (keine Ersatzleistungspflicht). Abbildungen und Zitate dienen lediglich dem Verkauf und stellen keine Publikation im Sinne des Urheberrechts dar. Alle Rechte an den Abbildungen und den zitierten Texten bleiben den Inhabern der Urheberrechte vorbehalten. Nachdrucke müssen in jedem Fall genehmigt werden. Versandkosten: innerhalb Deutschlands kostenfrei, innerhalb Europas: EUR 9.--, außerhalb Europas: EUR 18.-- „augenblicklich mit einer grösseren Arbeit beschäftigt“ Bernried 6.9.1897 1 ALBERT, EUGEN D' (1864-1932): Eigenhändige Postkarte mit Unterschrift und Adresse. Bernried 6.9.1897. Beidseitig beschrieben. EUR 400 An den Verleger Unico Hensel.