Quartet Dimensions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Analysis of the Six Duets for Violin and Viola by Michael Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE SIX DUETS FOR VIOLIN AND VIOLA BY MICHAEL HAYDN AND WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART by Euna Na Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University May 2021 Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee ______________________________________ Frank Samarotto, Research Director ______________________________________ Mark Kaplan, Chair ______________________________________ Emilio Colón ______________________________________ Kevork Mardirossian April 30, 2021 ii I dedicate this dissertation to the memory of my mentor Professor Ik-Hwan Bae, a devoted musician and educator. iii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................ iv List of Examples .............................................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................................................. vii Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Unaccompanied Instrumental Duet... ................................................................... 3 A General Overview -

Haydn London Symphony

Portrait of Franz Joseph Haydn by Thomas Hardy, 1791 WHAT MAKES IT GREAT?® HAYDN LONDON SYMPHONY 20 CONCERT PROGRAM Louis Babin Friday, February 10, 2017 Retrouvailles: Sesquie for Canada’s 150th* 7:30pm (TSO PREMIÈRE/TSO CO-COMMISSION) Rob Kapilow Rob Kapilow What Makes It Great?® conductor & host Haydn London Symphony Gary Kulesha* conductor Intermission Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 104 in D Major “London” I. Adagio – Allegro II. Andante III. Menuet: Allegro IV. Allegro spiritoso Audience Q&A with Rob Kapilow and Orchestra Please note that Louis Babin’s Retrouvailles is being recorded for online release at TSO.CA/CanadaMosaic. Tonight’s What Makes It Great?® program is all about listening. Paying attention. Noticing all the fantastic things in great music that race by at lightning speed, note by note, and measure by measure. Listening to a piece of music from the composer’s point of view—from the inside out. During the first half of the concert, we will look at selected passages from Franz Joseph Haydn’s Symphony No. 104 (“London”) and I will do everything in my power to get you inside the piece to Rob Kapilow hear what makes it tick and what makes it great. Then, after intermission, we will conductor perform the piece in its entirety, and you will hopefully listen to it with a whole & host new pair of ears. I am thrilled to be sharing this great music with you tonight. All you have to do is listen. 21 For a program note to Louis Babin’s Retrouvailles: Sesquie THE DETAILS for Canada’s 150th, please turn to pg. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Takács Quartet Beethoven String Quartet Cycle

Takács Quartet Beethoven String Quartet Cycle Concerts V and VI March 25–26, 2017 Rackham Auditorium Ann Arbor CONTENT Concert V Saturday, March 25, 8:00 pm 3 Beethoven’s Impact: Steven Mackey 7 Beethoven’s Impact: Adam Sliwinski 13 Concert VI Sunday, March 26, 4:00 pm 15 Beethoven’s Impact: Lowell Liebermann 18 Beethoven’s Impact: Augusta Read Thomas 21 Artists 25 Takács Quartet Concert V Edward Dusinberre / Violin Károly Schranz / Violin Geraldine Walther / Viola András Fejér / Cello Saturday Evening, March 25, 2017 at 8:00 Rackham Auditorium Ann Arbor 51st Performance of the 138th Annual Season 54th Annual Chamber Arts Series This evening’s presenting sponsor is the William R. Kinney Endowment. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. Special thanks to Steven Whiting for his participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. The Takács Quartet records for Hyperion and Decca/London Records. The Takács Quartet is Quartet-in-Residence at the University of Colorado in Boulder and are Associate Artists at Wigmore Hall, London. The Takács Quartet appears by arrangement with Seldy Cramer Artists. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. PROGRAM Beethoven String Quartets Concert V String Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 18, No. 6 Allegro con brio Adagio ma non troppo Scherzo: Allegro La malinconia: Adagio — Allegretto quasi Allegro String Quartet in F Major, Op. 135 Allegretto Vivace Lento assai e cantante tranquillo Grave — Allegro — Grave, ma non troppo tratto — Allegro Intermission String Quartet in C Major, Op. -

PDF 139.88KB Rps Abo Salomon Prize 2013

Press Release For release: Friday 10 January 2014 ‘Unsung heroine’ of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, violinist Catherine Arlidge, a “true advocate of the modern orchestral musician” awarded prestigious RPS/ABO Salomon Prize for orchestral musicians. Catherine Arlidge of the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra becomes the first violinist – and only the third ever recipient – of the RPS/ABO Salomon Prize, a prestigious award celebrating the outstanding contribution of orchestral players to the UK’s musical life. The UK boasts many of the world’s finest orchestras, many of which have trophy cabinets bursting with awards in testimony to their brilliance on the concert platform and in the recording studio. Yet, the contribution of individual musicians within an orchestra often goes unnoticed. The Salomon Prize* was created by the Royal Philharmonic Society and Association of British Orchestras in 2011 to celebrate the ‘unsung heroes’ of orchestral life; the orchestral players that make our orchestras great. The award is named after Johann Peter Salomon, violinist and founding member of the Philharmonic Society in 1813. Each year, players in all orchestras across the UK are asked to nominate a colleague who has been ‘an inspiration to their fellow players, fostered greater spirit of teamwork and shown commitment and dedication above and beyond the call of duty’. Catherine Arlidge, Sub Principal of the second violins, who has played with the CBSO for over 20 years, was nominated by her fellow musicians and the CBSO’s management for her creativity, energy and “great skill for motivating and inspiring colleagues and for engaging with her audience”. -

Rehearing Beethoven Festival Program, Complete, November-December 2020

CONCERTS FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 2020-2021 Friends of Music The Da Capo Fund in the Library of Congress The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress (RE)HEARING BEETHOVEN FESTIVAL November 20 - December 17, 2020 The Library of Congress Virtual Events We are grateful to the thoughtful FRIENDS OF MUSIC donors who have made the (Re)Hearing Beethoven festival possible. Our warm thanks go to Allan Reiter and to two anonymous benefactors for their generous gifts supporting this project. The DA CAPO FUND, established by an anonymous donor in 1978, supports concerts, lectures, publications, seminars and other activities which enrich scholarly research in music using items from the collections of the Music Division. The Anne Adlum Hull and William Remsen Strickland Fund in the Library of Congress was created in 1992 by William Remsen Strickland, noted American conductor, for the promotion and advancement of American music through lectures, publications, commissions, concerts of chamber music, radio broadcasts, and recordings, Mr. Strickland taught at the Juilliard School of Music and served as music director of the Oratorio Society of New York, which he conducted at the inaugural concert to raise funds for saving Carnegie Hall. A friend of Mr. Strickland and a piano teacher, Ms. Hull studied at the Peabody Conservatory and was best known for her duets with Mary Howe. Interviews, Curator Talks, Lectures and More Resources Dig deeper into Beethoven's music by exploring our series of interviews, lectures, curator talks, finding guides and extra resources by visiting https://loc.gov/concerts/beethoven.html How to Watch Concerts from the Library of Congress Virtual Events 1) See each individual event page at loc.gov/concerts 2) Watch on the Library's YouTube channel: youtube.com/loc Some videos will only be accessible for a limited period of time. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 115, 1995-1996

BOSTON > V SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ft SEIJIOZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR 9 6 S E O N The security of a trust, Fidelity investment expertise. A CLumlc Composition Fidelity Just as a Beethoven score is at its best when performed by a world- Pergonal class symphony — so, too, should your trust assets be managed by Triittt a financial company recognized Serviced globally for its investment expertise. Fidelity Investments. That's why Fidelity now offers a % managed trust or personalized estment management account or your portfolio of $400,000 or more/ For more information, visit Fidelity Investor Center or call Fidelity Pergonal Trust Services at 1-800-854-2829. Visit a Fidelity Investor Center Near You: Boston - Back Bay • Boston - Financial District Braintree, MA • Burlington, MA Fidelity Investments' SERVICES OFFERED ONLY THROUGH AUTHORIZED TRUST COMPANIES. TRUST SERVICES VARY BY STATE. FIDELITY BROKERAGE SERVICES, INC., MEMBER NYSE, SIPC. Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Fifteenth Season, 1995-96 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. J. P. Barger, Chairman Nicholas T. Zervas, President Peter A. Brooke, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Mrs. Edith L. Dabney, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson Nader F. Darehshori Edna S. Kalman Mrs. Robert B. Newman James F. Cleary Deborah B. Davis Allen Z. Kluchman Robert P. O'Block John E. Cogan, Jr. Nina L. Doggett George Krupp Peter C. Read Julian Cohen Avram J. Goldberg R. Willis Leith, Jr. Carol Scheifele-Holmes Chairman-elect William F. -

The Compositional Influence of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig Van Beethoven’S Early Period Works

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2018 Apr 18th, 12:30 PM - 1:45 PM The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works Mary L. Krebs Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Musicology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Krebs, Mary L., "The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works" (2018). Young Historians Conference. 7. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2018/oralpres/7 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THE COMPOSITIONAL INFLUENCE OF WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART ON LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S EARLY PERIOD WORKS Mary Krebs Honors Western Civilization Humanities March 19, 2018 1 Imagine having the opportunity to spend a couple years with your favorite celebrity, only to meet them once and then receiving a phone call from a relative saying your mother was about to die. You would be devastated, being prevented from spending time with your idol because you needed to go care for your sick and dying mother; it would feel as if both your dream and your reality were shattered. This is the exact situation the pianist Ludwig van Beethoven found himself in when he traveled to Vienna in hopes of receiving lessons from his role model, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. -

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Composer Fact Sheets Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) FAST FACTS • Learned music as a choirboy in Vienna • Dismissed from the choir for playing a practical joke on another choir member • Wrote, performed, and organized music and events for Prince Paul Anton Esterházy • Is known for his sense of humor that is very clear in his music Born: 1732 (Rohrau, Austria) Died: 1809 (Vienna, Austria) Joseph Haydn began his long musical career in St. Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, where he successfully auditioned into the choir. In the early 1700s, choirboys received a well-rounded education, so Haydn became proficient at singing, harpsichord, and violin. When he turned 17, his voice changed, so he left the cathedral choir to study music even further, realizing that he had received little training in the fundamentals of music. He studied and mastered music theory, the music of other composers, and took music composition lessons from a famous Italian composer and teacher. Haydn is also rumored to have been dismissed due to a practical joke he played on one of the other members of the choir. After his departure, Haydn struggled to support himself through part-time teaching and even street- serenading. He also performed freelance work for the chapel in Vienna, and filled in as an extra musician at balls that were given for orphaned children. Haydn began to gain a reputation, however, through his independent music studies and performing career. In 1761, Haydn entered the service of Prince Paul Anton Esterházy in Hungary. Haydn was required to compose music at a rapid pace, and to perform his works in concerts weekly, and to assist with chamber music concerts that took place nearly every day. -

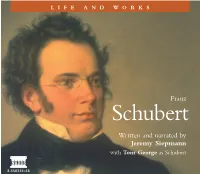

Franz Schubert Written and Narrated by Jeremy Siepmann with Tom George As Schubert

LIFE AND WORKS Franz Schubert Written and narrated by Jeremy Siepmann with Tom George as Schubert 8.558135–38 Life and Works: Franz Schubert Preface If music is ‘about’ anything, it’s about life. No other medium can so quickly or more comprehensively lay bare the very soul of those who make or compose it. Biographies confined to the limitations of text are therefore at a serious disadvantage when it comes to the lives of composers. Only by combining verbal language with the music itself can one hope to achieve a fully rounded portrait. In the present series, the words of composers and their contemporaries are brought to life by distinguished actors in a narrative liberally spiced with musical illustrations. Unlike the standard audio portrait, the music is not used here simply for purposes of illustration within a basically narrative context. Thus we often hear very substantial chunks, and in several cases whole movements, which may be felt by some to ‘interrupt’ the story; but as its title implies the series is not just about the lives of the great composers, it is also an exploration of their works. Dismemberment of these for ‘theatrical’ effect would thus be almost sacrilegious! Likewise, the booklet is more than a complementary appendage and may be read independently, with no loss of interest or connection. Jeremy Siepmann 8.558135–38 3 Life and Works: Franz Schubert © AKG Portrait of Franz Schubert, watercolour, by Wilhelm August Rieder 8.558135–38 Life and Works: Franz Schubert Franz Schubert(1797-1828) Contents Page Track Lists 6 Cast 11 1 Historical Background: The Nineteenth Century 16 2 Schubert in His Time 26 3 The Major Works and Their Significance 41 4 A Graded Listening Plan 68 5 Recommended Reading 76 6 Personalities 82 7 A Calendar of Schubert’s Life 98 8 Glossary 132 The full spoken text can be found on the CD-ROM part of the discs and at: www.naxos.com/lifeandworks/schubert/spokentext 8.558135–38 5 Life and Works: Franz Schubert 1 Piano Quintet in A major (‘Trout’), D. -

The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 203 SO 007 735 AUTHOR Pearl, Jesse; Carter, Raymond TITLE Music Listening--The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 42p.; An Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program; SO 007 734-737 are related documents PS PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetic Education; Course Content; Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; *Listening Habits; *Music Appreciation; *Music Education; Mucic Techniques; Opera; Secondary Grades; Teaching Techniques; *Vocal Music IDENTIFIERS Classical Period; Instrumental Music; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT This 9-week, Quinmester course of study is designed to teach the principal types of vocal, instrumental, and operatic compositions of the classical period through listening to the styles of different composers and acquiring recognition of their works, as well as through developing fastidious listening habits. The course is intended for those interested in music history or those who have participated in the performing arts. Course objectives in listening and musicianship are listed. Course content is delineated for use by the instructor according to historical background, musical characteristics, instrumental music, 18th century opera, and contributions of the great masters of the period. Seven units are provided with suggested music for class singing. resources for student and teacher, and suggestions for assessment. (JH) US DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH EDUCATION I MIME NATIONAL INSTITUTE -

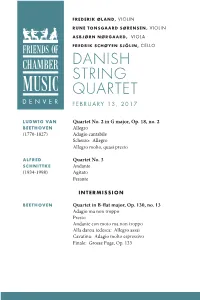

Danish String Quartet Denver February 13, 2017

FREDERIK ØLAND, VIOLIN RUNE TONSGAARD SØRENSEN, VIOLIN ASBJØRN NØRGAARD, VIOLA FREDRIK SCHØYEN SJÖLIN, CELLO DANISH STRING QUARTET DENVER FEBRUARY 13, 2017 LUDWIG VAN Quartet No. 2 in G major, Op. 18, no. 2 BEETHOVEN Allegro (1770-1827) Adagio cantabile Scherzo: Allegro Allegro molto, quasi presto ALFRED Quartet No. 3 SCHNITTKE Andante (1934-1998) Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION BEETHOVEN Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, no. 13 Adagio ma non troppo Presto Andante con moto ma non troppo Alla danza tedesca: Allegro assai Cavatina: Adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 FREDERIK ØLAND DANISH STRING QUARTET violin RUNE TONSGAARD Embodying the quintessential elements of a fine chamber SØRENSEN music ensemble, the Danish String Quartet has established violin a reputation for their integrated sound, impeccable ASBJØRN NØRGAARD intonation, and judicious balance. Since making their debut viola in 2002 at the Copenhagen Festival, the musical friends have demonstrated a passion for Scandinavian composers, FREDRIK SCHØYEN who they frequently incorporate into adventurous SJÖLIN contemporary programs, while also giving skilled and cello profound interpretations of the classical masters. The New York Times selected the quartet’s concerts as highlights of the season during their Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Two Residency, and in February 2016 they received the Borletti Buitoni Trust provided to support outstanding young artists in their international endeavors, joining an illustrious roster of past recipients. The Danish String Quartet’s 2016-2017 season includes debuts at the Edinburgh Festival and Zankel Hall at Carnegie Hall. In addition to over thirty North American engagements, the quartet’s robust international schedule takes them to their home country, Denmark, as well as throughout Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom, Poland, Israel, as well as Argentina, Peru, and Colombia.