The Golden Ratio As a Thematic Idea in Beethoven's B-Flat Major String

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Takács Quartet Beethoven String Quartet Cycle

Takács Quartet Beethoven String Quartet Cycle Concerts V and VI March 25–26, 2017 Rackham Auditorium Ann Arbor CONTENT Concert V Saturday, March 25, 8:00 pm 3 Beethoven’s Impact: Steven Mackey 7 Beethoven’s Impact: Adam Sliwinski 13 Concert VI Sunday, March 26, 4:00 pm 15 Beethoven’s Impact: Lowell Liebermann 18 Beethoven’s Impact: Augusta Read Thomas 21 Artists 25 Takács Quartet Concert V Edward Dusinberre / Violin Károly Schranz / Violin Geraldine Walther / Viola András Fejér / Cello Saturday Evening, March 25, 2017 at 8:00 Rackham Auditorium Ann Arbor 51st Performance of the 138th Annual Season 54th Annual Chamber Arts Series This evening’s presenting sponsor is the William R. Kinney Endowment. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. Special thanks to Steven Whiting for his participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. The Takács Quartet records for Hyperion and Decca/London Records. The Takács Quartet is Quartet-in-Residence at the University of Colorado in Boulder and are Associate Artists at Wigmore Hall, London. The Takács Quartet appears by arrangement with Seldy Cramer Artists. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. PROGRAM Beethoven String Quartets Concert V String Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 18, No. 6 Allegro con brio Adagio ma non troppo Scherzo: Allegro La malinconia: Adagio — Allegretto quasi Allegro String Quartet in F Major, Op. 135 Allegretto Vivace Lento assai e cantante tranquillo Grave — Allegro — Grave, ma non troppo tratto — Allegro Intermission String Quartet in C Major, Op. -

Quartet Dimensions

concert program ii: Quartet Dimensions JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)! July 21 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Sunday, July 21, 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts Fugue in E-flat Major, BWV 876, and Fugue in d minor, BWV 877, from at Menlo-Atherton Das wohltemperierte Klavier; arr. String Quartets nos. 7 and 8, K. 405 JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) PROGRAM OVERVIEW String Quartet in d minor, op. 76, no. 2, Quinten (1796) The string quartet medium, arguably the spinal column of the Allegro chamber music literature, did not exist in Bach’s lifetime. Yet Andante o più tosto allegretto Minuetto: Allegro ma non troppo even here, Bach’s legacy is inescapable. The fugues of his semi- Finale: Vivace assai nal The Well-Tempered Clavier inspired no less a genius than Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; Asbjørn Nørgaard, viola; Mozart, who arranged a set of them for string quartet. The influ- Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, cello ence of Bach’s architectural mastery permeates the ingenious DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Quinten Quartet of Joseph Haydn, the father of the modern Piano Quintet in g minor, op. 57 (1940) string quartet, and even Dmitry Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet, Prelude composed nearly two hundred years after Bach’s death. The Fugue Scherzo centerpiece of Beethoven’s Opus 132—the Heiliger Dankgesang Intermezzo CONCERT PROGRAMSCONCERT eines Genesenen an die Gottheit (“A Convalescent’s Holy Song Finale PROGRAMSCONCERT of Thanksgiving to the Divinity”)—recalls another Bachian signa- Gilbert Kalish, piano; Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; ture: the Baroque master’s sacred chorales. -

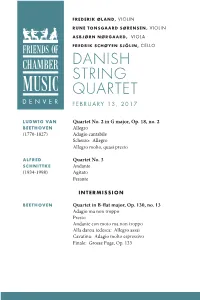

Danish String Quartet Denver February 13, 2017

FREDERIK ØLAND, VIOLIN RUNE TONSGAARD SØRENSEN, VIOLIN ASBJØRN NØRGAARD, VIOLA FREDRIK SCHØYEN SJÖLIN, CELLO DANISH STRING QUARTET DENVER FEBRUARY 13, 2017 LUDWIG VAN Quartet No. 2 in G major, Op. 18, no. 2 BEETHOVEN Allegro (1770-1827) Adagio cantabile Scherzo: Allegro Allegro molto, quasi presto ALFRED Quartet No. 3 SCHNITTKE Andante (1934-1998) Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION BEETHOVEN Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, no. 13 Adagio ma non troppo Presto Andante con moto ma non troppo Alla danza tedesca: Allegro assai Cavatina: Adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 FREDERIK ØLAND DANISH STRING QUARTET violin RUNE TONSGAARD Embodying the quintessential elements of a fine chamber SØRENSEN music ensemble, the Danish String Quartet has established violin a reputation for their integrated sound, impeccable ASBJØRN NØRGAARD intonation, and judicious balance. Since making their debut viola in 2002 at the Copenhagen Festival, the musical friends have demonstrated a passion for Scandinavian composers, FREDRIK SCHØYEN who they frequently incorporate into adventurous SJÖLIN contemporary programs, while also giving skilled and cello profound interpretations of the classical masters. The New York Times selected the quartet’s concerts as highlights of the season during their Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Two Residency, and in February 2016 they received the Borletti Buitoni Trust provided to support outstanding young artists in their international endeavors, joining an illustrious roster of past recipients. The Danish String Quartet’s 2016-2017 season includes debuts at the Edinburgh Festival and Zankel Hall at Carnegie Hall. In addition to over thirty North American engagements, the quartet’s robust international schedule takes them to their home country, Denmark, as well as throughout Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom, Poland, Israel, as well as Argentina, Peru, and Colombia. -

ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAMS 1997-2001 LOCATION: ROCKPORT ART ASSOCIATION 1997 June 12-July 6, 1997 David Deveau, Artistic Director

ROCKPORT CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL PROGRAMS 1997-2001 LOCATION: ROCKPORT ART ASSOCIATION 1997 June 12-July 6, 1997 David Deveau, artistic director Thursday, June 12, 1997 Opening Night Gala Concert & Champagne Reception The Piano Virtuoso Recital Series Russell Sherman, piano Ricordanza, No. 9 from The Transcendental Etudes Franz Liszt (1811-86) Wiegenlied (Cradle-song) Liszt Sonata in B minor Liszt Sech Kleine Klavierstucke (Six Piano Piece), OP. 19 (1912) Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951) Sonata No. 23 in F minor, Op. 57 “Appassionata” Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Friday, June 13, 1997 The International String Quartet Series The Shanghai Quartet Quartet in G major, Op. 77, No. 1, “Lobkowitz” Franz Josef Haydn (1732-1809) Poems from Tang Zhou Long (b.1953) Quartet No. 14 in D minor, D.810 “Death and the Maiden” Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Saturday, June 14, 1997 Chamber Music Gala Series Figaro Trio Trio for violin, cello and piano in C major, K.548 (1788) Wolfgang A. Mozart (1756-91) Duo for violin and cello, Op. 7 (1914) Zoltan Kodaly (1882-1967) Trio for violin, cello and piano in F minor, Op. 65 (1883) Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) Sunday, June 15, 1997 Chamber Music Gala Series Special Father’s Day Concert Richard Stoltzman, clarinet Janna Baty, soprano (RCMF Young Artist) | Andres Diaz, cello Meg Stoltzman, piano | Elaine Chew, piano (RCMF Young Artist) | Peter John Stoltzman, piano David Deveau, piano The Great Panjandrum (1989) Peter Child (b.1953) Sonata for clarinet and piano (1962) Francis Poulenc (1899-1964( Jazz Selections Selected Waltzes and Hungarian Dances for piano-four hands Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Trio in A minor for clarinet, cello and piano, Op. -

Beethoven's Grosse Fuge and Op. Vi

MEGAN ROSS THE POWER OF ALLUSION: BEETHOVEN’S GROSSE FUGE AND OP. VI* ABSTRACT Beethoven ha composto due finali estremamente differenti per il quartetto in Si bemolle maggiore, op. Il finale originariamente concepito, la Grosse Fugue, è un grande e importante movimento in più sezioni, mentre il secondo finale, cosiddetto ‘piccolo’, è un più leggero rondò-sonata, dalle caratteristiche ibride. La cospicua bibliografia prodotta intorno al quando e al perché Beethoven abbia composto i due movimenti, quasi sempre ha sostenuto la polarizzazione tra le due conclusioni. Tuttavia, è possibile identificare punti di contatto stringenti tra i due movimenti, più di quanto è stato riconosciuto in precedenza. In particolare, l’articolo mette in evidenza allusioni multiple o similitudini tra i due finali, in termini di elementi melodici, ritmici e formali, di texture, che esistono nella versione definitiva e che possono essere rintracciati a ritroso negli schizzi prepara- tori per il secondo finale. Il potere dell’allusione ci permette di collegare la distanza tra questi finali e ci aiuta a leggere il secondo finale come un ‘tardo’ non convenzionale la- voro, accanto all’originale. PAROLE CHIAVE Beethoven quartetto op. , Grosse Fugue, finale, allusione, schizzi SUMMARY Beethoven composed two strikingly different finales for his string quartet in B-flat Major, Op. The original Grosse Fugue finale is an immense and heavy multi-sectioned movement, while the second so-called “little” finale is a lighter sonata-rondo hybrid. The extensive body of scholarship surrounding when and why Beethoven composed both movements almost always promotes the polarity of the two endings. However, I argue that these two movements are more closely related than previously recognized. -

Elias String Quartet BEETHOVEN the Complete String Quartets

b0073_WH booklet template.qxd 08/12/2014 22:57 Page 1 Elias String Quartet BEETHOVEN The Complete String Quartets Op. 18 No. 4 Op. 74 ‘Harp’ Opp. 130 & 133 1 b0073_WH booklet template.qxd 08/12/2014 22:57 Page 2 Elias string QuartEt plays BEEthovEn – 1 There is something particularly special about replace the fugue with a slighter final movement. Beethoven’s cycle of string quartets. At the heart This does so much to change the experience of the of Beethoven’s life’s statement as a composer, work as a whole that the Elias String Quartet they are pieces that one simply needs to know. played Op. 130 twice in their Wigmore Hall cycle, The cycle of piano sonatas may be more complete. once with each finale – an excellent idea. The five cello sonatas are perhaps the most Arguably, if I had to choose a single Beethoven perfectly concise and representative series. The work to sum him up as a composer, this would be symphonies of course are the mightiest of all, it. Written on a grand scale, it contains the whole each a masterpiece. Every one of these cycles world within it: earthiness, humour, monstrous inspired and also weighed heavily upon the intellect, heaven and hell, redemption. One may generations that followed but the cycle of choose one’s own words of course because this sixteen string quartets has retained a special music is at once objective and also wonderfully status and reverence that perhaps eclipses all of abstract. It defies words. them. Why? The opening movement of Op. -

San Diego Symphony Orchestra Beethoven's

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA BEETHOVEN’S SYMPHONY NO. 5 A JACOBS MASTERWORKS CONCERT Edo de Waart, conductor January 17 and 18, 2020 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Grosse Fuge in B-flat Major, Op. 133 (Arr. By Felix Weingartner) JOHN ADAMS Violin Concerto Quarter note = 78 Chaconne: Body Through Which the Dream Flows Toccare Leila Josefowicz, violin INTERMISSION LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67 Allegro con brio Andante con moto Allegro Allegro Grosse Fuge in B-flat Major, Op. 133 (arr. Felix Weingartner) LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Born December 16, 1770, Bonn Died March 26, 1827, Vienna Beethoven composed his String Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 130 in 1825, and it was first performed in Vienna on March 21, 1826, almost exactly a year before his death. Long deaf, Beethoven did not attend the premiere, but waited across the street for reports from his friends. The massive six-movement quartet concluded with a long and difficult fugue, and when Beethoven’s friends told him that several of the shorter movements had proven so successful that they had to be repeated, the crusty old composer exploded: “Yes, these delicacies! Why not the fugue?” “Why not the fugue?” indeed. That fugue has been a point of contention ever since and probably will be forever. Is it the logical conclusion to a string quartet made up of quite dissimilar movements, or is that fugue – 17 minutes of some of Beethoven’s most violent and forbidding music – so independent a work that it should be removed from the quartet and performed separately? Beethoven’s publisher Matthias Artaria certainly believed the latter and wanted him to substitute a new finale and publish the fugue as a separate work. -

Beethoven's Op. 135 As 'Haydn' Quartet

barbara barry Op.135: Beethoven’s ‘Haydn’ quartet The year 1826 was a year of awful happenings and great achievements.1 y the autumn of 1826 Beethoven had finished the F major String Quartet op.135. 1826 saw the completion of two of the late string Bquartets, the C# minor (op.131) and the F major (op.135). The C# minor, written between December 1825 and July 1826, with its slow first move ment fugue and seven-movement plan, required intense, detailed work, with more sketches than for almost any other work except the Ninth Symphony.2 On 12 August 1826 Beethoven sends Schott the score with the ironic note: ‘Zusammengestohlen aus Verschiedenem diesem und jenem’ (cobbled together with filched bits of this and that). Coexisting with the artistic reality of compositional problem-solving and expressive delineation is the reality of physical existence: bouts of ill- health and the ongoing struggle with deafness; duplicitous negotiations 1. Thayer’s Life of Beethoven, with publishers; and circumstances that he tries to manipulate or control, rev. & ed. Elliot Forbes, 2 vols (Princeton, 1967), vol.2, in particular the contentious relationship with his nephew Karl, for whom p.973. he was the guardian.3 Virtually coinciding with the completion of op.131, 2. Robert Winter: ‘Plans tension between Beethoven and Karl reaches crisis point. After months of for the structure of the violent scenes, with Karl trying to assert his independence from Beethoven’s String Quartet in C# minor, op.131’, in Beethoven studies possessiveness, on 29 July Karl pawned his watch and bought two pistols. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven Grosse Fuge for String Quartet

PRE-CONCERT TALK TRANSCRIPT by Scott Burnham Ludwig van Beethoven Born December 16, 1770, Bonn, Germany. Died March 26, 1827, Vienna, Austria. Grosse Fuge for String Quartet The following is a transcript of the pre-concert lecture by Princeton University Professor and Beethoven scholar, Dr. Scott Burnham. This Grosse Fuge is a justly famous, even infamous, movement for string quartet. It probably represents the furthest limb Beethoven ever went out on, and he went out on quite a few limbs. He was quite limber, I guess you could say. This movement is uncompromising to the extreme, enigmatic, and even its context is a kind of paradox, for it stands as part of the string quartet Opus 130, but it also stands apart from the string quartet Opus 130. As the original finale of that late quartet, the Grosse Fuge serves as the tumultuous seed to which the tributaries of all the preceding movements inexorably run. But an anxious publisher talked Beethoven into separating the Grosse Fuge from the rest of the quartet and publishing it separately, in a version for four-hand piano. He was anxious about the difficulty of the piece, both in terms of – for the performers and for the listeners. Now, Beethoven’s last completed composition, before he passed away, was an alternative finale for the Opus 130 quartet, and it is in fact a masterly movement, much more in the scale of the rest of the quartet, but one that almost always disappoints, simply because it is not the Grosse Fuge. When speaking of the Grosse Fuge, everyone always quotes Igor Stravinsky, who said that the Grosse Fuge was absolutely contemporary and would stay contemporary forever. -

THE ARIEL QUARTET Alexandra Kazovsky, Violin Gershon Gerchikov

Sunday, April 25, 2021 The Westchester Chamber Music Society presents THE ARIEL QUARTET Alexandra Kazovsky, violin Gershon Gerchikov, violin Jan Grüning, viola Amit Even-Tov, cello Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) String Quartet in B-flat, Op. 130 Adagio ma non troppo—Allegro Presto Andante con moto, ma non troppo Alla danza tedesca: Allegro assai Cavatina: Adagio molto espressivo Finale: Allegro Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 Overture First Fugue Meno mosso e moderato Interlude and Second Fugue Thematic convergence and coda PROGRAM NOTES by Joshua Berrett, Ph.D. Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) String Quartet in B-flat, Op. 130 Beethoven had the aristocracy in the palm of his hand. There are names like Count Waldstein, Princes Lichnowsky and Lobkowitz, Countesses Therese and Josephine Brunsvick, Archduke Rudolf, Count Razumovsky, and quite a few more. Associating with Beethoven boosted their reputations, while Beethoven, as a free-lance composer and performer, depended on them to advance his career. With the approach of his final years, Beethoven’s stature was such that he could name his price. This is clear from a letter of November 9, 1822, sent from St. Petersburg by Prince Nicolas Galitzin, a self-described “passionate amateur of music” and student of the cello. He asks that Beethoven “compose one, two, or three new quartets, for which it would be a pleasure to recompense you fully whatever sum you might name. I would accept the dedication with gratitude.” The quartet trilogy in question refers to the Opp. 127, 130 (with the original Grosse Fuge as finale), and 132. -

The 2014 Great Lakes Festival Celebrates the Music and Influence

Contact: Jill Overacker Public Relations & Marketing Manager 248-559-2097 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [email protected] The 2014 Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival celebrates the music and influence of Johann Sebastian Bach “In the Shadow of Bach” will run from June 14th to the 29th SOUTHFIELD, Mich. – The music of Johann Sebastian Bach, the crowning composer of the Baroque era, will come to life at the 2014 Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival. Titled In the Shadow of Bach, the 21st annual festival will also explore Bach’s exceptional influence on subsequent composers. The Festival will open on Saturday, June 14 at Seligman Performing Arts Center. More than 20 concerts will take place in the two-week period. The festival will run through Sunday, June 29th. The Festival will welcome composer Peter Schickele as the 2014 Stone Composer-in-Residence. Schickele is well-known for presenting the “lost works” of his alter-ego, P.D.Q. Bach. Schickele will present the works of P.D.Q. Bach on Saturday, June 21 at Seligman Performing Arts Center and Monday, June 23 at Temple Beth El. “Pastorale for Flute and Strings,” a world premiere by Schickele, will be performed on Thursday, June 19 with a repeat performance on June 20 at Temple Beth El. Thirty-three year old Iranian composer, Sahba Aminikia, will serve as the 2014 Stone Composer Fellow. His new work, “Shab o Meh (Night and Fog)” will be performed on Thursday, June 26 at Kirk in the Hills Presbyterian Church. Returning artists will include 2014 Cleveland Quartet Award recipients, the Ariel Quartet. -

The Critical and Artistic Reception of Beethoven's

THE CRITICAL AND ARTISTIC RECEPTION OF BEETHOVEN’S STRING QUARTET IN C♯ MINOR, OP. 131 Megan Ross A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the College of Arts and Sciences. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Mark Evan Bonds Tim Carter Annegret Fauser Aaron Harcus Mark Katz ©2019 Megan Ross ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Megan Ross: The Critical and Artistic Reception of Beethoven’s String Quartet in C♯-Minor, Op. 131 (Under the direction of Mark Evan Bonds) Long viewed as the unfortunate products of a deaf composer, Ludwig van Beethoven’s “late” works are now widely regarded as the pinnacle of his oeuvre. While the reception of this music is often studied from the perspective of multiple works, my dissertation offers a different perspective by examining in detail the critical and artistic reception of a single late work, the String Quartet in C♯ minor, Op. 131. Critics have generally agreed that the string quartets best exemplify the composer’s late style, and that of these, Op. 131 stands out as the paradigmatic late quartet. I argue that this is because Op. 131 exhibits the greatest concentration of features typically associated with the late style. It is formally unconventional, with seven movements of grotesquely different proportions, to be played continuously, without a pause, as if to insist on the unity of the whole. It conspicuously avoids a sonata-form movement until its finale, opening instead with an extended fugue; the sonata-form finale, in turn, quotes from the fugue, again reinforcing the notion of formal wholeness.