San Diego Symphony Orchestra Beethoven's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saturday Playlist

October 26, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “To achieve great things, two things are needed: a plan, and not quite enough time.” — Leonard Bernstein Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 008 in G, "Evening" English Concert/Pinnock Archiv 423 098 028942309821 00:24 Buy Now! Scarlatti, D. Sonata in A, Kirkpatrick 212 Murray Perahia Sony 63380 07464633802 00:28 Buy Now! Grieg Symphonic Dances, Op. 64 Philharmonia Orchestra/Leppard Philips 438 380 02894388023 Academy of St. Martin-in-the- 01:00 Buy Now! Rossini Overture ~ Cinderella EMI 49155 077774915526 Fields/Marriner 01:09 Buy Now! Parry Elegy for Brahms London Philharmonic/Boult EMI 49022 07777490222 01:20 Buy Now! Brahms Sextet No. 1 in B flat, Op. 18 Stern/Lin/Laredo/Tree/Ma/Robinson Sony Classical 45820 07464458202 02:00 Buy Now! Mozart Fantasia in C minor, K. 475 Alicia de Larrocha RCA Red Seal 60453 090266045327 Lento assai ~ String Quartet in F, Op. 135 (arr. 02:15 Buy Now! Beethoven Royal Philharmonic/Rosekrans Telarc 80562 089408056222 for string orchestra) 02:27 Buy Now! Gade Symphony No. 7 in F, Op. 45 Stockholm Sinfonietta/Jarvi BIS 355 7318590003558 03:00 Buy Now! Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun Zoeller/Berlin Philharmonic/Karajan EMI 65914 724356591424 03:11 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Cello Sonata No. 1 in B flat, Op. 45 Rosen/Artymiw Bridge 9501 090404950124 03:37 Buy Now! Offenbach Offenbachiana Monte Carlo Philharmonic/Rosenthal Naxos 8.554005 N/A 04:01 Buy Now! Saint-Saëns Havanaise, Op. -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

Working List of Repertoire for Tenor Trombone Solo and Bass Trombone Solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers

Working List of Repertoire for tenor trombone solo and bass trombone solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers Working list v.2.4 ~ May 30, 2021 Prepared by Douglas Yeo, Guest Lecturer of Trombone Wheaton College Conservatory of Music Armerding Center for Music and the Arts www.wheaton.edu/conservatory 520 E. Kenilworth Avenue Wheaton, IL 60187 Email: [email protected] www.wheaton.edu/academics/faculty/douglas-yeo Works by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) Composers: Tenor trombone • Amis, Kenneth Preludes 1–5 (with piano) www.kennethamis.com • Barfield, Anthony Meditations of Sound and Light (with piano) Red Sky (with piano/band) Soliloquy (with trombone quartet) www.anthonybarfield.com 1 • Baker, David Concert Piece (with string orchestra) - Lauren Keiser Publishing • Chavez, Carlos Concerto (with orchestra) - G. Schirmer • Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel (arr. Ralph Sauer) Gypsy Song & Dance (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • DaCosta, Noel Four Preludes (with piano) Street Calls (unaccompanied) • Davis, Nathaniel Cleophas (arr. Aaron Hettinga) Oh Slip It Man (with piano) Mr. Trombonology (with piano) Miss Trombonism (with piano) Master Trombone (with piano) Trombone Francais (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • John Duncan Concerto (with orchestra) Divertimento (with string quartet) Three Proclamations (with string quartet) library.umkc.edu/archival-collections/duncan • Hailstork, Adolphus Cunningham John Henry’s Big (Man vs. Machine) (with piano) - Theodore Presser • Hong, Sungji Feromenis pnois (unaccompanied) • Lam, Bun-Ching Three Easy Pieces (with electronics) • Lastres, Doris Magaly Ruiz Cuasi Danzón (with piano) Tres Piezas (with piano) • Ma, Youdao Fantasia on a Theme of Yada Meyrien (with piano/orchestra) - Jinan University Press (ISBN 9787566829207) • McCeary, Richard Deming Jr. -

Takács Quartet Beethoven String Quartet Cycle

Takács Quartet Beethoven String Quartet Cycle Concerts V and VI March 25–26, 2017 Rackham Auditorium Ann Arbor CONTENT Concert V Saturday, March 25, 8:00 pm 3 Beethoven’s Impact: Steven Mackey 7 Beethoven’s Impact: Adam Sliwinski 13 Concert VI Sunday, March 26, 4:00 pm 15 Beethoven’s Impact: Lowell Liebermann 18 Beethoven’s Impact: Augusta Read Thomas 21 Artists 25 Takács Quartet Concert V Edward Dusinberre / Violin Károly Schranz / Violin Geraldine Walther / Viola András Fejér / Cello Saturday Evening, March 25, 2017 at 8:00 Rackham Auditorium Ann Arbor 51st Performance of the 138th Annual Season 54th Annual Chamber Arts Series This evening’s presenting sponsor is the William R. Kinney Endowment. Media partnership provided by WGTE 91.3 FM and WRCJ 90.9 FM. Special thanks to Steven Whiting for his participation in events surrounding this weekend’s performances. The Takács Quartet records for Hyperion and Decca/London Records. The Takács Quartet is Quartet-in-Residence at the University of Colorado in Boulder and are Associate Artists at Wigmore Hall, London. The Takács Quartet appears by arrangement with Seldy Cramer Artists. In consideration of the artists and the audience, please refrain from the use of electronic devices during the performance. The photography, sound recording, or videotaping of this performance is prohibited. PROGRAM Beethoven String Quartets Concert V String Quartet in B-flat Major, Op. 18, No. 6 Allegro con brio Adagio ma non troppo Scherzo: Allegro La malinconia: Adagio — Allegretto quasi Allegro String Quartet in F Major, Op. 135 Allegretto Vivace Lento assai e cantante tranquillo Grave — Allegro — Grave, ma non troppo tratto — Allegro Intermission String Quartet in C Major, Op. -

String Orchestra

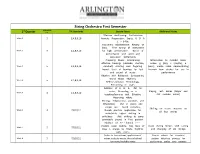

String Orchestra First Semester st Instructional 1 Quarter Days TN Standards Lesson Focus Additional Notes Effective Auditioning: Performance Week 1 5 2,4,8,9,10 Anxiety, Preparation, Scales G D A C F B-flat Instrument Maintenance: Review of basic. Fine tuning of instrument Week 2 5 2,4,8,9,10 for high performance. Basics of performance with wind and percussion instruments Preparing Music: Determining Introduction to melodic minor effective bowings (detache, martele, scales: g (vln), c (vla/clo), e Week 3 5 2,4,8,9,10 ricochet), creating own fingering (bass), create video demonstrating layout, Uses of bowings for feel fivemain bow strokes for use in and sound of music performance Rhythm and Rehearsal: Syncopation, World Music Rhythms, Week 4 5 2,4,8,9,10 Rehearsal/Italian Terminology, Performing in styles Addition of E, B, E-‐flat to scales, Recording as a Playing Test: Scales (Major and Week 5 4 2,4,8,9,10 teaching/learning tool, Effective AW melodic minor) Recording Habits Shifting: 3rdposition,½ position, and 5thposition. Use in scales and simple pre-‐heard melodies, Shifting on scales required on Week 6 4 7,8,10,11 thumb position application for all four strings violin/viola, higher shifting in cello/bass. Add shifting to parts previously played in first position Addition of A-‐flatand F-‐ sharpto scale routine, Key Quiz of Assist during Stripes with tuning Week 7 5 7,8,10,11 keys 5 sharps to 5flats, rhythms and changing of old strings with scales, Scales to two octaves, application of Create videos for standard Week 8 5 7,8,10,11 -

Quartet Dimensions

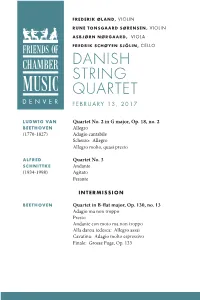

concert program ii: Quartet Dimensions JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685–1750)! July 21 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756–1791) Sunday, July 21, 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts Fugue in E-flat Major, BWV 876, and Fugue in d minor, BWV 877, from at Menlo-Atherton Das wohltemperierte Klavier; arr. String Quartets nos. 7 and 8, K. 405 JOSEPH HAYDN (1732–1809) PROGRAM OVERVIEW String Quartet in d minor, op. 76, no. 2, Quinten (1796) The string quartet medium, arguably the spinal column of the Allegro chamber music literature, did not exist in Bach’s lifetime. Yet Andante o più tosto allegretto Minuetto: Allegro ma non troppo even here, Bach’s legacy is inescapable. The fugues of his semi- Finale: Vivace assai nal The Well-Tempered Clavier inspired no less a genius than Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; Asbjørn Nørgaard, viola; Mozart, who arranged a set of them for string quartet. The influ- Fredrik Schøyen Sjölin, cello ence of Bach’s architectural mastery permeates the ingenious DMITRY SHOSTAKOVICH (1906–1975) Quinten Quartet of Joseph Haydn, the father of the modern Piano Quintet in g minor, op. 57 (1940) string quartet, and even Dmitry Shostakovich’s Piano Quintet, Prelude composed nearly two hundred years after Bach’s death. The Fugue Scherzo centerpiece of Beethoven’s Opus 132—the Heiliger Dankgesang Intermezzo CONCERT PROGRAMSCONCERT eines Genesenen an die Gottheit (“A Convalescent’s Holy Song Finale PROGRAMSCONCERT of Thanksgiving to the Divinity”)—recalls another Bachian signa- Gilbert Kalish, piano; Danish String Quartet: Frederik Øland, Rune Tonsgaard Sørensen, violins; ture: the Baroque master’s sacred chorales. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Roosevelt Instrumental Syllabus

Roosevelt HigH scHool instRumental music DepaRtment Instrumental Music Classes 2019-2020 Band(s) and Orchestra(s); Percussion Ensemble, Jazz Ensemble, and Marching Band Instructor: Mr. D’Angelo Contact: Roosevelt High School Office Hours: M-F 1st Hour Instrumental Music Department M-F Afterschool Tel : (734)759-5236 Email: [email protected] Teacher Schedule: (1) Marching Band /Prep Hour (2) Concert Band (3) Percussion Ensemble (4) String Orchestra (5) Symphony Band (5-C) Jazz Ensemble (TBD after school) (6) Chamber Strings (7) Music Appreciation 1) Class Descriptions: Marching Band Known as “The Wyandotte Marching Chiefs,” the marching band serves as the ambassador ensemble for the entire instrumental music program at Roosevelt High School and the Wyandotte community. In addition to performing at all home football games, the band occasionally travels to support the team at playoff games. Beyond the local appearances at football games, Wyandotte Homecoming parade, 4th of July Parade, Wyandotte Christmas Parade, and the Trenton Christmas Parade, “The Wyandotte Marching Chiefs” also perform a number of times in various marching band competitions throughout the state. These performances include the Michigan School Band and Orchestra association Marching Band festival, and several competitions sponsored by the Michigan Competing Bands Association. The marching band concludes its fall marching season with a formal concert (Fall Festival) recapping the ensembles achievements. The Marching Band offers students experience in a number of musical and non-musical activities. Marching band members can gain valuable experience in leadership, time management, coordination, communication, as well as build upon many musical skills. Participation in this ensemble is open to all RHS students’ grades 9-12 playing a wind or percussion instrument or utilizing Color guard equipment or dance. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: a DIVERSIFIED SELECTION of 20

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: A DIVERSIFIED SELECTION OF 20TH CENTURY OBOE & ENGLISH HORN CONCERTI Yeon-Jee Sohn, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2003 Dissertation directed by: Professor Mark Hill Department of Music My determination in pursuing a soloistic career both as an oboist and as an English horn player is certainly a primary force behind this Doctoral Dissertation Project’s theme . Equally important to me, though , was to notice - both as an orchestral player and as a listener – the relative abse nce of much Twentieth -Century Oboe/English Horn repertoire in the concert hall, over the air waves , and the in the recording market . Therefore, I have felt the need to explore less- frequently heard concerti. Even so, I elected to open my series of recitals with Richard Strauss’ well -known masterwork, in the hope of conveying my stance and belief that the lesser- known repertoire I chose is by all means competitive - in terms of compositional craftsmanship, musical value, and sheer impact on the audience - even when heard side by side with an accepted staple of our Century . If this repertoire is under -represented in the concert hall, the amount of scholarly research available is also scarce . Indeed, it is a challenge to gather information beyond the purely biographical and circumstantial data. Finally, my choice of repertoire is necessarily limited in quantity to number of works I can perform in three recitals , but I beli eve it is nonetheless stylistically representative of the body of work produced in this Century for my two instruments. I have ele cted to present a collection of works that I believe represent a variety of 20th century musical styles from significant composers of the period, and which are particularly worthy musically. -

Danish String Quartet Denver February 13, 2017

FREDERIK ØLAND, VIOLIN RUNE TONSGAARD SØRENSEN, VIOLIN ASBJØRN NØRGAARD, VIOLA FREDRIK SCHØYEN SJÖLIN, CELLO DANISH STRING QUARTET DENVER FEBRUARY 13, 2017 LUDWIG VAN Quartet No. 2 in G major, Op. 18, no. 2 BEETHOVEN Allegro (1770-1827) Adagio cantabile Scherzo: Allegro Allegro molto, quasi presto ALFRED Quartet No. 3 SCHNITTKE Andante (1934-1998) Agitato Pesante INTERMISSION BEETHOVEN Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 130, no. 13 Adagio ma non troppo Presto Andante con moto ma non troppo Alla danza tedesca: Allegro assai Cavatina: Adagio molto espressivo Finale: Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 FREDERIK ØLAND DANISH STRING QUARTET violin RUNE TONSGAARD Embodying the quintessential elements of a fine chamber SØRENSEN music ensemble, the Danish String Quartet has established violin a reputation for their integrated sound, impeccable ASBJØRN NØRGAARD intonation, and judicious balance. Since making their debut viola in 2002 at the Copenhagen Festival, the musical friends have demonstrated a passion for Scandinavian composers, FREDRIK SCHØYEN who they frequently incorporate into adventurous SJÖLIN contemporary programs, while also giving skilled and cello profound interpretations of the classical masters. The New York Times selected the quartet’s concerts as highlights of the season during their Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Two Residency, and in February 2016 they received the Borletti Buitoni Trust provided to support outstanding young artists in their international endeavors, joining an illustrious roster of past recipients. The Danish String Quartet’s 2016-2017 season includes debuts at the Edinburgh Festival and Zankel Hall at Carnegie Hall. In addition to over thirty North American engagements, the quartet’s robust international schedule takes them to their home country, Denmark, as well as throughout Germany, Austria, the United Kingdom, Poland, Israel, as well as Argentina, Peru, and Colombia. -

A Case Study of an Award Winning Public School String Orchestra Program

A CASE STUDY OF AN AWARD WINNING PUBLIC SCHOOL STRING ORCHESTRA PROGRAM Wing Man Fu A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2009 Committee: Elaine J. Colprit, Advisor Penny T. Kruse ii ABSTRACT Elaine Colprit, Advisor The purpose of this study was to examine the history, growth, and development of an award winning public school string program. This study provided a description of a model of an excellent orchestra program and produced a general benefit to novice teachers who are setting up new programs, and to music educators by adding to our knowledge of the unique characteristics of a successful string program. There were three major sections of discussion in this study: (1) preparation for setting up a string program; (2) delivery of instruction in elementary, middle school, and high school levels of the program; and (3) continued growth, development, and support of the program. This research was accomplished by analysis of the following data: (a) live observations of class instruction at elementary, middle school, and high school, (b) orchestra handbooks and documents regarding curriculum and other guidelines; and (c) transcripts of interviews with faculty from Upper Arlington City Schools. Results show that individual faculty qualifications and experience prepare them to teach all levels of string classes. Based on their experiences, they are able to create an organized curriculum, design goal directed instructional plans, teach effectively as a team, and sustain a successful string program. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. -

The Golden Ratio As a Thematic Idea in Beethoven's B-Flat Major String

Durational Thematicism and the Temporal Process: The Golden Ratio as a Thematic Idea in Beethoven's B-flat Major String Quartet, No. 13, Op. 130, and the Grosse Fuge, Op. 133 David Suggate A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the degree, Master of Arts, Music Supervised by Dr. Graeme Downes University of Otago, New Zealand April 2017 Abstract This thesis explores the use of Fibonacci sequences, and other rhythmic proportions corresponding to the golden ratio in Beethoven's string quartet No. 13, Op. 130, and its original finale, the Grosse Fuge, Op. 133. This provides a new angle for considering the problem of the \time-experience" in late Beethoven. The golden ratio not only forms a common thread in all of the late period quartets, but I argue that it is an essential \thematic idea" within the discourse of the whole work, one bearing implications for the unfolding of the temporal process. Firstly I outline preliminary examples of how the composer \exposes" the golden ratio at the beginnings of the Opp. 127, 130, 133 and 135 quartets. They are expressed through such means as five beats on the tonic, three on the dominant, or five beats at forte, and three at piano, or through a particular rhythmic pattern lasting five beats, and another lasting eight, and so on, each amounting to a 5:3 or 5:8 ratio, corresponding to the Fibonacci sequence, and thus to the golden ratio. In order to build a framework for durational thematicism I review literature on problems surrounding the golden ratio in Western music, the nature of rhythm, metre and pulse in tonal music, and on the \time-experience" in late Beethoven.