A Case Study of an Award Winning Public School String Orchestra Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saturday Playlist

October 26, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “To achieve great things, two things are needed: a plan, and not quite enough time.” — Leonard Bernstein Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Awake! 00:01 Buy Now! Haydn Symphony No. 008 in G, "Evening" English Concert/Pinnock Archiv 423 098 028942309821 00:24 Buy Now! Scarlatti, D. Sonata in A, Kirkpatrick 212 Murray Perahia Sony 63380 07464633802 00:28 Buy Now! Grieg Symphonic Dances, Op. 64 Philharmonia Orchestra/Leppard Philips 438 380 02894388023 Academy of St. Martin-in-the- 01:00 Buy Now! Rossini Overture ~ Cinderella EMI 49155 077774915526 Fields/Marriner 01:09 Buy Now! Parry Elegy for Brahms London Philharmonic/Boult EMI 49022 07777490222 01:20 Buy Now! Brahms Sextet No. 1 in B flat, Op. 18 Stern/Lin/Laredo/Tree/Ma/Robinson Sony Classical 45820 07464458202 02:00 Buy Now! Mozart Fantasia in C minor, K. 475 Alicia de Larrocha RCA Red Seal 60453 090266045327 Lento assai ~ String Quartet in F, Op. 135 (arr. 02:15 Buy Now! Beethoven Royal Philharmonic/Rosekrans Telarc 80562 089408056222 for string orchestra) 02:27 Buy Now! Gade Symphony No. 7 in F, Op. 45 Stockholm Sinfonietta/Jarvi BIS 355 7318590003558 03:00 Buy Now! Debussy Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun Zoeller/Berlin Philharmonic/Karajan EMI 65914 724356591424 03:11 Buy Now! Mendelssohn Cello Sonata No. 1 in B flat, Op. 45 Rosen/Artymiw Bridge 9501 090404950124 03:37 Buy Now! Offenbach Offenbachiana Monte Carlo Philharmonic/Rosenthal Naxos 8.554005 N/A 04:01 Buy Now! Saint-Saëns Havanaise, Op. -

Sacha M. Joseph-Mathews, Phd. Curriculum Vitae

Sacha M. Joseph-Mathews, PhD. Curriculum Vitae Contact Information University Eberhardt School of Business University of the Pacific Stockton, CA Phone: (209) 946-2628 Fax: (209) 946-2586 Email: [email protected] UNIVERSITY POSITIONS Associate Professor- Marketing, 2006- present Faculty Chair, 2014-2016 Eberhardt School of Business University of the Pacific, (Tenured) Instructor, College of Continuing Education California State University-Sacramento, 2009- Present Instructor, University of the West Indies, Summer 2013 Instructor, College of Business Florida State University, 2002-2006 Instructor, Kaiser College, 2004 EDUCATION Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL Doctor of Philosophy, June 2006 Major Field: Marketing Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL Master of Science, 2004, Major: Hospitality and Tourism Management University of the West Indies, Mona, Jamaica Bachelor of Arts, 1998, Major: Mass Communication (First Class Honors) RESEARCH INTERESTS Marketing Strategy and Consumer Behavior Customer Value Determination and Measurement, Ethical Consumption, Green Consumer Behavior, Brand Equity and Loyalty. Sacha M. Joseph-Mathews • Eberhardt School of Business • University of the Pacific Services Services- Social Entrepreneurship, Service Environment, Brand Personality, E-Commerce, Services Marketing, Retailing Consumer Ethnicity and Buying Power, Retailing and Environmental Sustainability, Tourism and Hospitality Management (Destination Branding, Eco-tourism, Cultural and Heritage Tourism, Value Determination) International -

Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: a Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras

Texas Music Education Research, 2012 V. D. Baker Edited by Mary Ellen Cavitt, Texas State University—San Marcos Gender Association with Stringed Instruments: A Four-Decade Analysis of Texas All-State Orchestras Vicki D. Baker Texas Woman’s University The violin, viola, cello, and double bass have fluctuated in both their gender acceptability and association through the centuries. This can partially be attributed to the historical background of women’s involvement in music. Both church and society rigidly enforced rules regarding women’s participation in instrumental music performance during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. In the 1700s, Antonio Vivaldi established an all-female string orchestra and composed music for their performance. In the early 1800s, women were not allowed to perform in public and were severely limited in their musical training. Towards the end of the 19th century, it became more acceptable for women to study violin and cello, but they were forbidden to play in professional orchestras. Societal beliefs and conventions regarding the female body and allure were an additional obstacle to women as orchestral musicians, due to trepidation about their physiological strength and the view that some instruments were “unsightly for women to play, either because their presence interferes with men’s enjoyment of the female face or body, or because a playing position is judged to be indecorous” (Doubleday, 2008, p. 18). In Victorian England, female cellists were required to play in problematic “side-saddle” positions to prevent placing their instrument between opened legs (Cowling, 1983). The piano, harp, and guitar were deemed to be the only suitable feminine instruments in North America during the 19th Century in that they could be used to accompany ones singing and “required no facial exertions or body movements that interfered with the portrait of grace the lady musician was to emanate” (Tick, 1987, p. -

Working List of Repertoire for Tenor Trombone Solo and Bass Trombone Solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers

Working List of Repertoire for tenor trombone solo and bass trombone solo by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) and Women Composers Working list v.2.4 ~ May 30, 2021 Prepared by Douglas Yeo, Guest Lecturer of Trombone Wheaton College Conservatory of Music Armerding Center for Music and the Arts www.wheaton.edu/conservatory 520 E. Kenilworth Avenue Wheaton, IL 60187 Email: [email protected] www.wheaton.edu/academics/faculty/douglas-yeo Works by People of Color/People of the Global Majority (POC/PGM) Composers: Tenor trombone • Amis, Kenneth Preludes 1–5 (with piano) www.kennethamis.com • Barfield, Anthony Meditations of Sound and Light (with piano) Red Sky (with piano/band) Soliloquy (with trombone quartet) www.anthonybarfield.com 1 • Baker, David Concert Piece (with string orchestra) - Lauren Keiser Publishing • Chavez, Carlos Concerto (with orchestra) - G. Schirmer • Coleridge-Taylor, Samuel (arr. Ralph Sauer) Gypsy Song & Dance (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • DaCosta, Noel Four Preludes (with piano) Street Calls (unaccompanied) • Davis, Nathaniel Cleophas (arr. Aaron Hettinga) Oh Slip It Man (with piano) Mr. Trombonology (with piano) Miss Trombonism (with piano) Master Trombone (with piano) Trombone Francais (with piano) www.cherryclassics.com • John Duncan Concerto (with orchestra) Divertimento (with string quartet) Three Proclamations (with string quartet) library.umkc.edu/archival-collections/duncan • Hailstork, Adolphus Cunningham John Henry’s Big (Man vs. Machine) (with piano) - Theodore Presser • Hong, Sungji Feromenis pnois (unaccompanied) • Lam, Bun-Ching Three Easy Pieces (with electronics) • Lastres, Doris Magaly Ruiz Cuasi Danzón (with piano) Tres Piezas (with piano) • Ma, Youdao Fantasia on a Theme of Yada Meyrien (with piano/orchestra) - Jinan University Press (ISBN 9787566829207) • McCeary, Richard Deming Jr. -

The Effects of Digital Music Distribution" (2012)

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Research Papers Graduate School Spring 4-5-2012 The ffecE ts of Digital Music Distribution Rama A. Dechsakda [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/gs_rp The er search paper was a study of how digital music distribution has affected the music industry by researching different views and aspects. I believe this topic was vital to research because it give us insight on were the music industry is headed in the future. Two main research questions proposed were; “How is digital music distribution affecting the music industry?” and “In what way does the piracy industry affect the digital music industry?” The methodology used for this research was performing case studies, researching prospective and retrospective data, and analyzing sales figures and graphs. Case studies were performed on one independent artist and two major artists whom changed the digital music industry in different ways. Another pair of case studies were performed on an independent label and a major label on how changes of the digital music industry effected their business model and how piracy effected those new business models as well. I analyzed sales figures and graphs of digital music sales and physical sales to show the differences in the formats. I researched prospective data on how consumers adjusted to the digital music advancements and how piracy industry has affected them. Last I concluded all the data found during this research to show that digital music distribution is growing and could possibly be the dominant format for obtaining music, and the battle with piracy will be an ongoing process that will be hard to end anytime soon. -

String Orchestra

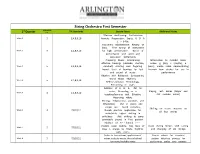

String Orchestra First Semester st Instructional 1 Quarter Days TN Standards Lesson Focus Additional Notes Effective Auditioning: Performance Week 1 5 2,4,8,9,10 Anxiety, Preparation, Scales G D A C F B-flat Instrument Maintenance: Review of basic. Fine tuning of instrument Week 2 5 2,4,8,9,10 for high performance. Basics of performance with wind and percussion instruments Preparing Music: Determining Introduction to melodic minor effective bowings (detache, martele, scales: g (vln), c (vla/clo), e Week 3 5 2,4,8,9,10 ricochet), creating own fingering (bass), create video demonstrating layout, Uses of bowings for feel fivemain bow strokes for use in and sound of music performance Rhythm and Rehearsal: Syncopation, World Music Rhythms, Week 4 5 2,4,8,9,10 Rehearsal/Italian Terminology, Performing in styles Addition of E, B, E-‐flat to scales, Recording as a Playing Test: Scales (Major and Week 5 4 2,4,8,9,10 teaching/learning tool, Effective AW melodic minor) Recording Habits Shifting: 3rdposition,½ position, and 5thposition. Use in scales and simple pre-‐heard melodies, Shifting on scales required on Week 6 4 7,8,10,11 thumb position application for all four strings violin/viola, higher shifting in cello/bass. Add shifting to parts previously played in first position Addition of A-‐flatand F-‐ sharpto scale routine, Key Quiz of Assist during Stripes with tuning Week 7 5 7,8,10,11 keys 5 sharps to 5flats, rhythms and changing of old strings with scales, Scales to two octaves, application of Create videos for standard Week 8 5 7,8,10,11 -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

Roosevelt Instrumental Syllabus

Roosevelt HigH scHool instRumental music DepaRtment Instrumental Music Classes 2019-2020 Band(s) and Orchestra(s); Percussion Ensemble, Jazz Ensemble, and Marching Band Instructor: Mr. D’Angelo Contact: Roosevelt High School Office Hours: M-F 1st Hour Instrumental Music Department M-F Afterschool Tel : (734)759-5236 Email: [email protected] Teacher Schedule: (1) Marching Band /Prep Hour (2) Concert Band (3) Percussion Ensemble (4) String Orchestra (5) Symphony Band (5-C) Jazz Ensemble (TBD after school) (6) Chamber Strings (7) Music Appreciation 1) Class Descriptions: Marching Band Known as “The Wyandotte Marching Chiefs,” the marching band serves as the ambassador ensemble for the entire instrumental music program at Roosevelt High School and the Wyandotte community. In addition to performing at all home football games, the band occasionally travels to support the team at playoff games. Beyond the local appearances at football games, Wyandotte Homecoming parade, 4th of July Parade, Wyandotte Christmas Parade, and the Trenton Christmas Parade, “The Wyandotte Marching Chiefs” also perform a number of times in various marching band competitions throughout the state. These performances include the Michigan School Band and Orchestra association Marching Band festival, and several competitions sponsored by the Michigan Competing Bands Association. The marching band concludes its fall marching season with a formal concert (Fall Festival) recapping the ensembles achievements. The Marching Band offers students experience in a number of musical and non-musical activities. Marching band members can gain valuable experience in leadership, time management, coordination, communication, as well as build upon many musical skills. Participation in this ensemble is open to all RHS students’ grades 9-12 playing a wind or percussion instrument or utilizing Color guard equipment or dance. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: a DIVERSIFIED SELECTION of 20

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: A DIVERSIFIED SELECTION OF 20TH CENTURY OBOE & ENGLISH HORN CONCERTI Yeon-Jee Sohn, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2003 Dissertation directed by: Professor Mark Hill Department of Music My determination in pursuing a soloistic career both as an oboist and as an English horn player is certainly a primary force behind this Doctoral Dissertation Project’s theme . Equally important to me, though , was to notice - both as an orchestral player and as a listener – the relative abse nce of much Twentieth -Century Oboe/English Horn repertoire in the concert hall, over the air waves , and the in the recording market . Therefore, I have felt the need to explore less- frequently heard concerti. Even so, I elected to open my series of recitals with Richard Strauss’ well -known masterwork, in the hope of conveying my stance and belief that the lesser- known repertoire I chose is by all means competitive - in terms of compositional craftsmanship, musical value, and sheer impact on the audience - even when heard side by side with an accepted staple of our Century . If this repertoire is under -represented in the concert hall, the amount of scholarly research available is also scarce . Indeed, it is a challenge to gather information beyond the purely biographical and circumstantial data. Finally, my choice of repertoire is necessarily limited in quantity to number of works I can perform in three recitals , but I beli eve it is nonetheless stylistically representative of the body of work produced in this Century for my two instruments. I have ele cted to present a collection of works that I believe represent a variety of 20th century musical styles from significant composers of the period, and which are particularly worthy musically. -

A Piece of History

A Piece of History Theirs is one of the most distinctive and recognizable sounds in the music industry. The four-part harmonies and upbeat songs of The Oak Ridge Boys have spawned dozens of Country hits and a Number One Pop smash, earned them Grammy, Dove, CMA, and ACM awards and garnered a host of other industry and fan accolades. Every time they step before an audience, the Oaks bring four decades of charted singles, and 50 years of tradition, to a stage show widely acknowledged as among the most exciting anywhere. And each remains as enthusiastic about the process as they have ever been. “When I go on stage, I get the same feeling I had the first time I sang with The Oak Ridge Boys,” says lead singer Duane Allen. “This is the only job I've ever wanted to have.” “Like everyone else in the group,” adds bass singer extraordinaire, Richard Sterban, “I was a fan of the Oaks before I became a member. I’m still a fan of the group today. Being in The Oak Ridge Boys is the fulfillment of a lifelong dream.” The two, along with tenor Joe Bonsall and baritone William Lee Golden, comprise one of Country's truly legendary acts. Their string of hits includes the Country-Pop chart-topper Elvira, as well as Bobbie Sue, Dream On, Thank God For Kids, American Made, I Guess It Never Hurts To Hurt Sometimes, Fancy Free, Gonna Take A Lot Of River and many others. In 2009, they covered a White Stripes song, receiving accolades from Rock reviewers. -

Sunday Playlist

October 20, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “I was obliged to be industrious. Whoever is equally industrious will succeed equally well.” — Johann Sebastian Bach Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Buy 00:01 Chopin Barcarolle in F sharp, Op. 60 Sviatoslav Richter Orfeo 491 981 4011790491127 Awake! Now! Buy Amsterdam Combattimento 00:11 Wassenaer Concerto in A NM Classics 92030 N/A Now! Consort/Vriend Buy Cypress Performing 00:21 Beethoven String Quartet No. 14 in C sharp minor, Op. 131 Cypress String Quartet n/a 666449766121 Now! Arts Association Buy 01:01 Brahms Academic Festival Overture, Op.80 Black Dyke Band/Childs Naxos 8.570726 74731307276 Now! Buy 01:11 Handel Suite in G minor for piano Keith Jarrett ECM 1530 781182153028 Now! Buy 01:22 Kalinnikov Symphony No. 1 in G minor Scottish National Orchestra/Jarvi Chandos 8611 5014682861120 Now! Buy Reference 02:01 Alfven Swedish Rhapsody No. 1, Op. 19 "Midsummer Vigil" Minnesota Orchestra/Oue 80 030911108021 Now! Recordings Buy Laird/Houghton/Brown/Acad. 02:14 Vivaldi Concerto in D for 2 Trumpets & Violin, RV 563 Philips 412 892 028941289223 Now! SMF/Marriner Buy 02:22 Debussy Images for Orchestra London Symphony/Previn EMI 47001 n/a Now! Buy 03:01 Martucci Symphony No. 1 in D minor, Op. 75 Philharmonia/d'Avalos ASV 675 5011975067528 Now! Buy 03:43 Schubert Impromptu in F minor, D. 935 No. 4 Alfred Brendel Philips 456 727 028945672724 Now! Buy 03:50 Purcell The Fairy Queen: Suite from Act 4 Concert of Nations/Savall Auvidis 8583 3298490085837 Now! Buy 04:00 Pierné Viennoise Loire Philharmonic/Derveaux EMI Classics 63950 077776395029 Now! Buy 04:11 Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. -

Trombonesandorchestra.Pdf

A Nieweg Chart 3 Solo Trombones with Orchestra or 3 Solo Trombones and Solo Tuba with Orchestra The publishing details of 16 works composed for these combinations: BOURGEOIS, Derek (b. Kingston-on-Thames, England, 16 October 1941) Concerto for 3 Trombones Op.56 3 Soli Trombones, Percussion, String Orchestra Pub: Warwick Music © 2003 Code: TB018 $160.95 [price per website 1/9/2011] Score and set for sale from any music dealer. Performed by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and San Francisco Symphony Trombones. 3 Trombones & Piano (55 p.) (+ optional percussion) Code: TB418 $39.95 <http://warwickmusic.com/Composers/A++C/Derek+Bourgeois/Bourgeois+Concerto+for+3+Trombones+orchestra> About the composer: <http://warwickmusic.com/composers/a+-+c/derek+bourgeois> < http://www.derekbourgeois.com/index.htm> Also published for 3 Trombones & Wind Band $120.95 ========================= van DELDEN, Lex [birth name- Alexander Zwaap] (b. Amsterdam, NL 10 Sept 1919; d. Amsterdam, NL 1 July 1988) Piccola musica concertata Op. 79 (1963) 3 Trombones, Timpani and String Orchestra Dur: 12' Premier: Amsterdam NL, 19 March1963 Pub: Donemus, NL ©1963 Contact: Donemus Music Center, The Netherlands, Rokin 111, 1012 KN Amsterdam Tel: +31 (0)20 344 60 00; Fax: +31 (0)20 673 35 88 Email: [email protected] website: <http://www.donemus.nl/page.php?pagina=home&lang=EN> To order score:< http://webshop.mcn.nl/portal/catalog/mcn_productlist.php?work=316216&language=en> Also available as an import from T. Presser. Orchestra Set: Rental agent: T. Presser, King of Prussia, Pa <www.presser.com> <[email protected]> Territory Represented: World (except British or Dutch controlled countries) About the composer: <http://www.lexvandelden.nl> ========================= DUBENSKY, Arcady (b.