Simply Beethoven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elaine Fitz Gibbon

Elaine Fitz Gibbon »Beethoven und Goethe blieben die Embleme des kunstliebenden Deutschlands, für jede politische Richtung unantastbar und ebenso als Chiffren manipulierbar« (Klüppelholz 2001, 25-26). “Beethoven and Goethe remained the emblems of art-loving Germany: untouchable for every political persuasion, and likewise, as ciphers, just as easily manipulated.”1 The year 2020 brought with it much more than collective attempts to process what we thought were the uniquely tumultuous 2010s. In addition to causing the deaths of over two million people worldwide, the Covid-19 pandemic has further exposed the extraordinary inequities of U.S.-American society, forcing a long- overdue reckoning with the entrenched racism that suffuses every aspect of American life. Within the realm of classical music, institutions have begun conversations about the ways in which BIPOC, and in particular Black Americans, have been systematically excluded as performers, audience members, administrators and composers: a stark contrast with the manner in which 2020 was anticipated by those same institutions before the pandemic began. Prior to the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, they looked to 2020 with eager anticipation, provoking a flurry of activity around a singular individual: Ludwig van Beethoven. For on December 16th of that year, Beethoven turned 250. The banners went up early. In 2019 on Instagram, Beethoven accounts like @bthvn_2020, the “official account of the Beethoven Anniversary Year,” sprang up. The Twitter hashtags #beethoven2020 and #beethoven250 were (more or less) trending. Prior to the spread of the virus, passengers flying in and out of Chicago’s O’Hare airport found themselves confronted with a huge banner that featured an iconic image of Beethoven’s brooding face, an advertisement for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s upcoming complete cycle Current Musicology 107 (Fall 2020) ©2020 Fitz Gibbon. -

A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2019 A master of music recital in clarinet Lucas Randall University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2019 Lucas Randall Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Randall, Lucas, "A master of music recital in clarinet" (2019). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 1005. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/1005 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A MASTER OF MUSIC RECITAL IN CLARINET An Abstract of a Recital Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Lucas Randall University of Northern Iowa December, 2019 This Recital Abstract by: Lucas Randall Entitled: A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet has been approved as meeting the recital abstract requirement for the Degree of Master of Music. ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Amanda McCandless, Chair, Recital Committee ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Stephen Galyen, Recital Committee Member ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Ann Bradfield, Recital Committee Member ____________ ________________________________________________ Date Dr. Jennifer Waldron, Dean, Graduate College This Recital Performance by: Lucas Randall Entitled: A Master of Music Recital in Clarinet Date of Recital: November 22, 2019 has been approved as meeting the recital requirement for the Degree of Master of Music. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

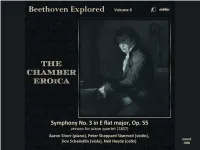

BEETHOVEN Explored Volume 6

BEETHOVEN Explored volume 6 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”) in E flat major, Op 55 (1803) Version for piano quartet, published Vienna, 1807 1 I Allegro con brio 18:18 2 II Marcia Funebre: Adagio assai 13:22 3 III Scherzo: Allegro vivace 6:13 4 IV Allegro molto 11:08 total CD duration 49:01 Peter Sheppard Skærved violin Dov Scheindlin viola Neil Heyde cello Aaron Shorr piano msvcd 2008 0809730008825 On the piano Quartet version of the Eroica Symphony - a player’s perspective Playing music written in the ‘pre-recording age’, I try to remember that, the predominant experience of orchestral and operatic music was in arrangement. Even with regular concert-going, people only had limited opportunities to hear any work. At the beginning of the 1800s, there was an enormous market of arrangements for home use, ranging from solo- violin transcriptions of melodies from operas, through works for chamber ensemble, ‘enlargements’ of piano works, re- instrumentations of other works, and reductions of orchestral pieces. An important ‘point of sale’ for much of this type of chamber music, was that it should function in a number of configurations. Duo transcriptions of opera arias were written so that they could be played by flutes or violins, and transcriptions involving piano usually functioned acceptably with all the ‘accompanying’ melody instruments missed out. It was in these versions that most people learnt the popular repertoire, playing or listening in the home or salon. It would be three decades into the 1800s before ‘full scores’ of orchestral pieces became available for study; Robert Schumann, writing in his 1841 ‘Marriage Diary’ with his new wife, Clara, spoke of his wish for a library of these for the two of them to work at together, playing the orchestra scores at the piano. -

Frauenleben in Magenza

www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Frauenleben in Magenza Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender seit 1991 und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz Frauenleben in Magenza Frauenleben in Magenza Die Porträts jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen aus dem Mainzer Frauenkalender und Texte zur Frauengeschichte im jüdischen Mainz 3 Frauenleben in Magenza Impressum Herausgeberin: Frauenbüro Landeshauptstadt Mainz Stadthaus Große Bleiche Große Bleiche 46/Löwenhofstraße 1 55116 Mainz Tel. 06131 12-2175 Fax 06131 12-2707 [email protected] www.mainz.de/frauenbuero Konzept, Redaktion, Gestaltung: Eva Weickart, Frauenbüro Namenskürzel der AutorInnen: Reinhard Frenzel (RF) Martina Trojanowski (MT) Eva Weickart (EW) Mechthild Czarnowski (MC) Bildrechte wie angegeben bei den Abbildungen Titelbild: Schülerinnen der Bondi-Schule. Privatbesitz C. Lebrecht Druck: Hausdruckerei 5. überarbeitete und erweiterte Auflage Mainz 2021 4 Frauenleben in Magenza Vorwort des Oberbürgermeisters Die Geschichte jüdischen Lebens und Gemein- Erstmals erschienen ist »Frauenleben in Magen- delebens in Mainz reicht weit zurück in das 10. za« aus Anlass der Eröffnung der Neuen Syna- Jahrhundert, sie ist damit auch die Geschichte goge im Jahr 2010. Weitere Auflagen erschienen der jüdischen Frauen dieser Stadt. 2014 und 2015. Doch in vielen historischen Betrachtungen von Magenza, dem jüdischen Mainz, ist nur selten Die Veröffentlichung basiert auf den Porträts die Rede vom Leben und Schicksal jüdischer jüdischer Frauen und Mädchen und auf den Frauen und Mädchen. Texten zu Einrichtungen jüdischer Frauen und Dabei haben sie ebenso wie die Männer zu al- Mädchen, die seit 1991 im Kalender »Blick auf len Zeiten in der Stadt gelebt, sie haben gelernt, Mainzer Frauengeschichte« des Frauenbüros gearbeitet und den Alltag gemeistert. -

One Day, Two Exciting, Family-Friendly Events!

Tempo Symphony Friends Newsletter 2019-20 Season - January 2020 One Day, Two Exciting, CSO AT-A-GLANCE Family-Friendly Events! TCHAIKOVSKY On January 25th at 2:00 p.m., the have to admit that many of the & BEETHOVEN CSO will present its annual hour- film scores are from movies that SAT., FEB. 29TH • 7:30 PM CHEYENNE CIVIC CENTER long family matinee, Heroes and were my favorites when I was Enjoy the Barber of Seville Overture, Villains. The Orchestra will present younger: Superman, Raiders of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto and a second concert, Blockbusters the Lost Ark, Robin Hood, Dances Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7! & Beethoven, as part of its with Wolves, etc. I am also excited Masterpiece series that evening about the Lord of the Rings music. MAHLER & at 7:30pm. These annual movie- Both the Saturday night concert BEETHOVEN themed performances are extremely and the Saturday afternoon SAT., MAR. 21ST • 7:30 PM popular because they provide matinee will be truly spectacular, CHEYENNE CIVIC CENTER audience members an opportunity with a large orchestra performing The celebration of Beethoven continues with the Egmont Overture to listen to accessible music in a fun incredible, dramatic and powerful and Eroica. Also featuring Mahler’s atmosphere. music.” Songs of a Wayfarer and “I am Lost to the World” The concerts will include Superman At the Matinee, the doors to the March, Raiders of the Lost Ark Civic Center will open at 1:00 RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK March, and March of the Resistance p.m. This will give attendees IN CONCERT from The Force Awakens, all the opportunity to mingle with SAT., APR. -

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL and INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors

The Seventh Season Being Mendelssohn CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL AND INSTITUTE July 17–August 8, 2009 David Finckel and Wu Han, Artistic Directors Music@Menlo Being Mendelssohn the seventh season july 17–august 8, 2009 david finckel and wu han, artistic directors Contents 3 A Message from the Artistic Directors 5 Welcome from the Executive Director 7 Being Mendelssohn: Program Information 8 Essay: “Mendelssohn and Us” by R. Larry Todd 10 Encounters I–IV 12 Concert Programs I–V 29 Mendelssohn String Quartet Cycle I–III 35 Carte Blanche Concerts I–III 46 Chamber Music Institute 48 Prelude Performances 54 Koret Young Performers Concerts 57 Open House 58 Café Conversations 59 Master Classes 60 Visual Arts and the Festival 61 Artist and Faculty Biographies 74 Glossary 76 Join Music@Menlo 80 Acknowledgments 81 Ticket and Performance Information 83 Music@Menlo LIVE 84 Festival Calendar Cover artwork: untitled, 2009, oil on card stock, 40 x 40 cm by Theo Noll. Inside (p. 60): paintings by Theo Noll. Images on pp. 1, 7, 9 (Mendelssohn portrait), 10 (Mendelssohn portrait), 12, 16, 19, 23, and 26 courtesy of Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz/Art Resource, NY. Images on pp. 10–11 (landscape) courtesy of Lebrecht Music and Arts; (insects, Mendelssohn on deathbed) courtesy of the Bridgeman Art Library. Photographs on pp. 30–31, Pacifica Quartet, courtesy of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Theo Noll (p. 60): Simone Geissler. Bruce Adolphe (p. 61), Orli Shaham (p. 66), Da-Hong Seetoo (p. 83): Christian Steiner. William Bennett (p. 62): Ralph Granich. Hasse Borup (p. 62): Mary Noble Ours. -

The Compositional Influence of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig Van Beethoven’S Early Period Works

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2018 Apr 18th, 12:30 PM - 1:45 PM The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works Mary L. Krebs Clackamas High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Musicology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Krebs, Mary L., "The Compositional Influence of olfW gang Amadeus Mozart on Ludwig van Beethoven’s Early Period Works" (2018). Young Historians Conference. 7. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2018/oralpres/7 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THE COMPOSITIONAL INFLUENCE OF WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART ON LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN’S EARLY PERIOD WORKS Mary Krebs Honors Western Civilization Humanities March 19, 2018 1 Imagine having the opportunity to spend a couple years with your favorite celebrity, only to meet them once and then receiving a phone call from a relative saying your mother was about to die. You would be devastated, being prevented from spending time with your idol because you needed to go care for your sick and dying mother; it would feel as if both your dream and your reality were shattered. This is the exact situation the pianist Ludwig van Beethoven found himself in when he traveled to Vienna in hopes of receiving lessons from his role model, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. -

The Pedagogical Legacy of Johann Nepomuk Hummel

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE PEDAGOGICAL LEGACY OF JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL. Jarl Olaf Hulbert, Doctor of Philosophy, 2006 Directed By: Professor Shelley G. Davis School of Music, Division of Musicology & Ethnomusicology Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837), a student of Mozart and Haydn, and colleague of Beethoven, made a spectacular ascent from child-prodigy to pianist- superstar. A composer with considerable output, he garnered enormous recognition as piano virtuoso and teacher. Acclaimed for his dazzling, beautifully clean, and elegant legato playing, his superb pedagogical skills made him a much sought after and highly paid teacher. This dissertation examines Hummel’s eminent role as piano pedagogue reassessing his legacy. Furthering previous research (e.g. Karl Benyovszky, Marion Barnum, Joel Sachs) with newly consulted archival material, this study focuses on the impact of Hummel on his students. Part One deals with Hummel’s biography and his seminal piano treatise, Ausführliche theoretisch-practische Anweisung zum Piano- Forte-Spiel, vom ersten Elementar-Unterrichte an, bis zur vollkommensten Ausbildung, 1828 (published in German, English, French, and Italian). Part Two discusses Hummel, the pedagogue; the impact on his star-students, notably Adolph Henselt, Ferdinand Hiller, and Sigismond Thalberg; his influence on musicians such as Chopin and Mendelssohn; and the spreading of his method throughout Europe and the US. Part Three deals with the precipitous decline of Hummel’s reputation, particularly after severe attacks by Robert Schumann. His recent resurgence as a musician of note is exemplified in a case study of the changes in the appreciation of the Septet in D Minor, one of Hummel’s most celebrated compositions. -

Schiller and Music COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Schiller and Music COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Schiller and Music r.m. longyear UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 54 Copyright © 1966 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Longyear, R. M. Schiller and Music. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1966. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.5149/9781469657820_Longyear Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Longyear, R. M. Title: Schiller and music / by R. M. Longyear. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 54. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1966] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 66064498 | isbn 978-1-4696-5781-3 (pbk: alk. paper) | isbn 978-1-4696-5782-0 (ebook) Subjects: Schiller, Friedrich, 1759-1805 — Criticism and interpretation. -

Chapter 16: Beethoven I. Life and Early Works A. Introduction 1

Chapter 16: Beethoven I. Life and Early Works A. Introduction 1. Beethoven was compared to Mozart early in his life, and the older composer noted his potential in a famous quote to “keep your eyes on him.” 2. Beethoven did not arrive in Vienna to stay until he was twenty-two, when Count Waldstein told him to receive the spirit of Mozart from Haydn’s tutelage. B. Life and Works, Periods and Styles 1. Beethoven’s music is seen often as autobiographical. 2. The stages of his career correspond to changing styles in his music: early, middle, late. C. Early Beethoven 1. Beethoven gave his first public performance at age seven, playing pieces from Bach’s “Well-Tempered Clavier,” among others. 2. He published his first work at eleven. 3. He became court organist in Bonn at age ten. 4. His first important compositions date from 1790 and were shown to Haydn, who agreed to teach him in 1792. 5. The lessons with Haydn didn’t last long, because Haydn went to England. Beethoven then gained recognition as a pianist among aristocratic circles in Vienna. 6. His first success in Vienna as a composer was his second piano concerto and three trios. Thus his own instrument was the main one for his early publications. a. This is perhaps best demonstrated in his piano sonatas, which show signs of his own abilities of performer, improviser, and composer. b. The Pathetique sonata illustrates the experimentation inherent in Beethoven’s music, challenging expectations. 7. Until 1800 he was better known as a performer than a composer; however, this soon changed, particularly with his first symphony and septet, Op. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven: Triumph Over a Life of Tragedy

Ludwig van Beethoven: Triumph Over a Life of Tragedy Madeline Brashaw Senior Division Historical Paper Paper Length: 2,448 words “It seemed unthinkable for me to leave the world forever before I had produced all that I felt Heiligenstadt Testament called upon to produce,” Ludwig van Beethoven wrote in shortly before he passed away. Ludwig van Beethoven practiced music his entire life. He told people that he did not know what he would do without music. Beethoven was brought up during the Classical Period which was defined and determined by its clear characteristics such as its emphasis on beauty, elegance, and balance, and by the variety and contrast within the musical pieces. It is said that his music altered the course of musical history and that it modified the Classical Period (Classical Music). Sadly, Beethoven’s career came to a halt when he began to lose his hearing, and it became nearly impossible for him to compose and conduct his works. The tragic loss of Beethoven’s hearing led to his triumph in changing musical history. Beethoven was brought into this world in December of 1770. As a child, Ludwig van Beethoven often had a sad life. He had no friends and had nobody to care for him. The one thing that he did have, and he used almost every day, was his music. Beethoven’s main instruments were the piano and the violin. As a child, he even composed his own music at times. His father, Johann van Beethoven, was young Beethoven’s first music teacher. As a child, his father harshly pushed him in his musical studies.