Essays on the Main Themes of BTHVN2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributi Alla Bibliografia Di G. Paisiello 239 Nazione. Cm. 17

U. Rolandi - Contributi alla bibliografia di G. Paisiello 239 nazione. Cm. 17><11 - pagg. 64, in 3 atti. Poeta (F. Livigni) non no- minato. Nome del Paisiello. La 1.a esecuzione avvenne a Venezia (T. S. Moisè, C. 1773) e non a Napoli (D. C.) dove fu dato nella seguente estate al T. Nuovo. - 32. - L'IPERMESTRA. Padova, Nuovo, 1791 (v. Sonneck). Bru- nelli (Teatri di Padova p. 285) la dice « già scritta in Russia ». Ignoto al D. C. " L' Isola d i s a b i t a t a, cantata su testo del Metastasio. Li- sbona, T. S. Carlo, E. 1799. Libretto in Biblioteca S. Cecilia (Roma). Ignoto al D. C. e ad altri. * I e f te sa c r i f i c i u m. Eseguito a, Venezia (Conservatorio Men- dicanti). Il libretto trovasi alla Bibl. S. Cecilia (Roma), ma è senza data. Il Carvalhaes — da cui deriva il libretto stesso -- dice essere 1774. Non trovo ricordato questo lavoro dal D. C. o da altri. * La Lavandara astuta. v. Il Matrimonio inaspettato. * La Locanda (e la Locandiera) v. 11 Fanatico in berlina. 33. - LUCIO PAPIRIO I DITTATORE Lisbona, Salvaterra, 1775 (v. Sonneck). * Madama l'umorista v. La Dama umorista. * 11 Maestro di scuola napolitano. v. La Scuffiara amante. * Il Marchese Tulipano. v. Il e7'Catrimonio inaspettato. * La Ma s c h e r a t a. Con questo titolo fu data al Ballhuset di Stocolma, I'l 1 dicembre 1788 un'opera « con musica del Sacchini e del Paisiello ». Forse si trattò di un'opera pasticcio, caso frequente allora. -

8.573726 Ries Booklet.Pdf

573726 bk Ries EU.qxp_573726 bk Ries EU 28/03/2018 11:31 Page 2 Ferdinand Ries (1784–1838) Stefan Stroissnig Cello Sonatas The Austrian pianist Stefan Stroissnig (b. 1985), studied in Vienna and at Ferdinand Ries was baptised in Bonn on 28 November cello concerto. Ries’s dedication of these two works to the Royal College of Music in London. His concert activity as a soloist 1784. Today his name is rarely mentioned without a Bernhard Romberg, from whom he also received cello has taken him around the world and to the most important concert reference to Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827), even if lessons, might have been an attempt to use the famous houses in Europe. He is recognised for his interpretations of works by it is likely that it was only after his arrival in Vienna on 29 name to gain attention. Ries had done the same in the Schubert and for 20th- and 21st-century repertoire. He has performed December 1802 that Ries had significant contact with dedication of his Piano Sonatas, Op. 1 to Beethoven, where works by Olivier Messiaen, Friedrich Cerha, Claude Vivier, Morton Beethoven. Ries’ father, Franz Anton Ries (1755–1846) he claimed to be Beethoven’s ‘sole student’ and ‘friend’. Feldman, Ernst Krenek as well as piano concertos by John Cage and was the archbishopric concertmaster and one of However, Ries and Romberg ended up performing Pascal Dusapin. He is a regular guest at many prominent festivals, and Beethoven’s teachers, before Beethoven left for Vienna in the Cello Sonatas, Op. 20 and Op. -

Sinfonie Inedite Sinfonie

THE UNPUBLISHED SYMPHONIES UNPUBLISHED THE SINFONIE INEDITE SINFONIE Fondazione Benefica Kathleen Foreman Casali, Fondazione De Claricini Dornpacher Claricini De Fondazione Casali, Foreman Kathleen Benefica Fondazione Fondazione Ada e Antonio Giacomini, Fondazione CRTrieste, CRTrieste, Fondazione Giacomini, Antonio e Ada Fondazione Provincia di Trieste, Comune di Trieste – Museo Revoltella, Revoltella, Museo – Trieste di Comune Trieste, di Provincia Con il sostegno di: sostegno il Con who have supported in this effort. this in supported have who Very grateful to Federica Galli Foundation and to Lorenza Salamon, Salamon, Lorenza to and Foundation Galli Federica to grateful Very Motta di Livenza, 1741 - Bonn, 1801 Bonn, - 1741 Livenza, di Motta che ci hanno aiutato in questa iniziativa. questa in aiutato hanno ci che Grazie alla Fondazione Federica Galli e a Lorenza Salamon, Lorenza a e Galli Federica Fondazione alla Grazie Studio Bertin, Milan Bertin, Studio project: Graphic Jean Suzanne Chaloux Suzanne Jean by: Translated Bruno Belli Bruno notes: Booklet Bacino di San Marco, 1984/85 (Courtesy Salamon Gallery, Milan) Gallery, Salamon (Courtesy 1984/85 Marco, San di Bacino Federica Galli, Venezia, Venezia, Galli, Federica image: Cover Gattuso Claudio and Caldara Federico engineer: sound and Recording 2014 2014 7 , 6 January recording: of Date th th Bottenicco di Moimacco (Cividale del Friuli) Friuli) del (Cividale Moimacco di Bottenicco Villa De Claricini, De Villa at: Recorded Production for Concerto: Concerto: for Production Andrea Maria -

574040-41 Itunes Beethoven

BEETHOVEN Chamber Music Piano Quartet in E flat major • Six German Dances Various Artists Ludwig van ¡ Piano Quartet in E flat major, Op. 16 (1797) 26:16 ™ I. Grave – Allegro ma non troppo 13:01 £ II. Andante cantabile 7:20 BEE(1T77H0–1O827V) En III. Rondo: Allegro, ma non troppo 5:54 1 ¢ 6 Minuets, WoO 9, Hess 26 (c. 1799) 12:20 March in D major, WoO 24 ‘Marsch zur grossen Wachtparade ∞ No. 1 in E flat major 2:05 No. 2 in G major 1:58 2 (Grosser Marsch no. 4)’ (1816) 8:17 § No. 3 in C major 2:29 March in C major, WoO 20 ‘Zapfenstreich no. 2’ (c. 1809–22/23) 4:27 ¶ 3 • No. 4 in F major 2:01 4 Polonaise in D major, WoO 21 (1810) 2:06 ª No. 5 in D major 1:50 Écossaise in D major, WoO 22 (c. 1809–10) 0:58 No. 6 in G major 1:56 5 3 Equali, WoO 30 (1812) 5:03 º 6 Ländlerische Tänze, WoO 15 (version for 2 violins and double bass) (1801–02) 5:06 6 No. 1. Andante 2:14 ⁄ No. 1 in D major 0:43 No. 2 in D major 0:42 7 No. 2. Poco adagio 1:42 ¤ No. 3. Poco sostenuto 1:05 ‹ No. 3 in D major 0:38 8 › No. 4 in D minor 0:43 Adagio in A flat major, Hess 297 (1815) 0:52 9 fi No. 5 in D major 0:42 March in B flat major, WoO 29, Hess 107 ‘Grenadier March’ No. -

Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann's Phantasie in C Major Michiko Inouye [email protected]

Wellesley College Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive Honors Thesis Collection 2014 A Compositional Personalization: Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann's Phantasie in C Major Michiko Inouye [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection Recommended Citation Inouye, Michiko, "A Compositional Personalization: Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann's Phantasie in C Major" (2014). Honors Thesis Collection. 224. https://repository.wellesley.edu/thesiscollection/224 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Wellesley College Digital Scholarship and Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Compositional Personalization: Influences of Late Beethoven Piano Sonatas on Schumann’s Phantasie in C Major Michiko O. Inouye Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in the Wellesley College Music Department April 2014 Copyright 2014 Michiko Inouye Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the wonderful guidance, feedback, and mentorship of Professor Charles Fisk. I am deeply appreciative of his dedication and patience throughout this entire process. I am also indebted to my piano teacher of four years at Wellesley, Professor Lois Shapiro, who has not only helped me grow as a pianist but through her valuable teaching has also led me to many realizations about Op. 111 and the Phantasie, and consequently inspired me to come up with many of the ideas presented in this thesis. Both Professor Fisk and Professor Shapiro have given me the utmost encouragement in facing the daunting task of both writing about and working to perform such immortal pieces as the Phantasie and Op. -

Juilliard415 Program Notes

PROGRAM NOTES The connected realms of madness and enchantment were endlessly fascinating to the Baroque imagination. People who are mad, or who are under some kind of spell, act beyond themselves in unexpected and disconcerting ways. Perhaps because early modern culture was so highly hierarchical, 17th- and 18th-century composers found these moments where social rules were broken and things were not as they seem — these eruptions of disorder — as fertile ground for musical invention. Our concert today explores how some very different composers used these themes to create strange and wonderful works to delight and astonish their listeners. We begin in late 17th-century England at a moment when London theaters were competing to stage ever more spectacular productions. Unlike in other countries, the idea of full-blown opera did not quite take root in England. Instead, the taste was for semi-operas where spoken plays shared the stage with astonishing special effects and elaborate musical numbers. One of the biggest Restoration theaters in London was the Dorset Garden House, which opened in 1671. Its impresario, Thomas Betterton, had gone twice to France to study the theatrical machinery perfected by the Paris Opéra. Betterton went on to stage lavish versions of Shakespeare, packed with interpolated musical numbers and coups de théâtre. The last of these was a magnificent version of Shakespeare’s Midsummer Night’s Dream, now called “The Fairy Queen,” produced for the 1691-92 season. In between the acts of Shakespeare, Betterton introduced a series of Las Vegas-like show stoppers. A dance for six monkeys? A symphony while swans float down an onstage river? A chaconne for twenty-four Chinese dancers? Anything is possible in this world of enchantment, where things are not what they seem. -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

Beethoven, Bonn and Its Citizens

Beethoven, Bonn and its citizens by Manfred van Rey The beginnings in Bonn If 'musically minded circles' had not formed a citizens' initiative early on to honour the city's most famous son, Bonn would not be proudly and joyfully preparing to celebrate his 250th birthday today. It was in Bonn's Church of St Remigius that Ludwig van Beethoven was baptized on 17 December 1770; it was here that he spent his childhood and youth, received his musical training and published his very first composition at the age of 12. Then the new Archbishop of Cologne, Elector Max Franz from the house of Habsburg, made him a salaried organist in his renowned court chapel in 1784, before dispatching him to Vienna for further studies in 1792. Two years later Bonn, the residential capital of the electoral domain of Cologne, was occupied by French troops. The musical life of its court came to an end, and its court chapel was disbanded. If the Bonn music publisher Nikolaus Simrock (formerly Beethoven’s colleague in the court chapel) had not issued several original editions and a great many reprints of Beethoven's works, and if Beethoven's friend Ferdinand Ries and his father Franz Anton had not performed concerts of his music in Bonn and Cologne, little would have been heard about Beethoven in Bonn even during his lifetime. The first person to familiarise Bonn audiences with Beethoven's music at a high artistic level was Heinrich Karl Breidenstein, the academic music director of Bonn's newly founded Friedrich Wilhelm University. To celebrate the anniversary of his baptism on 17 December 1826, he offered the Bonn première of the Fourth Symphony in his first concert, devoted entirely to Beethoven. -

The University of Chicago Objects of Veneration

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO OBJECTS OF VENERATION: MUSIC AND MATERIALITY IN THE COMPOSER-CULTS OF GERMANY AND AUSTRIA, 1870-1930 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY ABIGAIL FINE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2017 © Copyright Abigail Fine 2017 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES.................................................................. v LIST OF FIGURES.......................................................................................... vi LIST OF TABLES............................................................................................ ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................................................................. x ABSTRACT....................................................................................................... xiii INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER 1: Beethoven’s Death and the Physiognomy of Late Style Introduction..................................................................................................... 41 Part I: Material Reception Beethoven’s (Death) Mask............................................................................. 50 The Cult of the Face........................................................................................ 67 Part II: Musical Reception Musical Physiognomies............................................................................... -

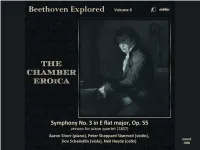

BEETHOVEN Explored Volume 6

BEETHOVEN Explored volume 6 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): Symphony No. 3 (“Eroica”) in E flat major, Op 55 (1803) Version for piano quartet, published Vienna, 1807 1 I Allegro con brio 18:18 2 II Marcia Funebre: Adagio assai 13:22 3 III Scherzo: Allegro vivace 6:13 4 IV Allegro molto 11:08 total CD duration 49:01 Peter Sheppard Skærved violin Dov Scheindlin viola Neil Heyde cello Aaron Shorr piano msvcd 2008 0809730008825 On the piano Quartet version of the Eroica Symphony - a player’s perspective Playing music written in the ‘pre-recording age’, I try to remember that, the predominant experience of orchestral and operatic music was in arrangement. Even with regular concert-going, people only had limited opportunities to hear any work. At the beginning of the 1800s, there was an enormous market of arrangements for home use, ranging from solo- violin transcriptions of melodies from operas, through works for chamber ensemble, ‘enlargements’ of piano works, re- instrumentations of other works, and reductions of orchestral pieces. An important ‘point of sale’ for much of this type of chamber music, was that it should function in a number of configurations. Duo transcriptions of opera arias were written so that they could be played by flutes or violins, and transcriptions involving piano usually functioned acceptably with all the ‘accompanying’ melody instruments missed out. It was in these versions that most people learnt the popular repertoire, playing or listening in the home or salon. It would be three decades into the 1800s before ‘full scores’ of orchestral pieces became available for study; Robert Schumann, writing in his 1841 ‘Marriage Diary’ with his new wife, Clara, spoke of his wish for a library of these for the two of them to work at together, playing the orchestra scores at the piano. -

Musica E Teatro in Un Archivio Di Frammenti Del Sette E Ottocento

BUGANI FABRIZIO Musica e teatro in un archivio di frammenti del Sette e Ottocento Estratto da QE, I - 2009/0 http://www.archivi.beniculturali.it/ASMO/QE Fabrizio Bugani - Musica e teatro in un archivio di frammenti del Sette e Ottocento 1. Introduzione L’indagine sulle fonti musicali e sulle relative fonti bibliografiche - uno dei risvolti del- la biblioteconomia musicale - consente di rendere nuovamente fruibili dati ed informa- zioni del passato attraverso la ricostruzione della rete di relazioni culturali a cui le fonti erano riconducibili e la loro adeguata contestualizzazione storica. La relazione illustra sinteticamente il risultato di un lavoro di ricerca che ha impegnato chi scrive dal 2002 al 2004, nell’esame di uno dei fondi musicali meno indagati tra quelli custoditi presso la Biblioteca Estense Universitaria di Modena; esame svolto du- rante un tirocinio in Biblioteca e concretizzatosi nella tesi di laurea Frammenti di musi- ca del Sette e Ottocento nella Biblioteca Estense Universitaria di Modena. L’indagine compiuta attraverso l’analisi dei manoscritti e la consultazione delle fonti d’archivio ha permesso di individuare i legami diretti e indiretti del fondo con le vicen- de della famiglia Austria-Este e della città di Modena, e di determinare l’articolazione del fondo identificando i nuclei originari di appartenenza. Fondamentale, nel lavoro di attribuzione dei manoscritti ad ambiti di provenienza inequivocabili, lo studio dei cata- loghi e degli inventari storici posseduti dalla Biblioteca e di pertinenti cataloghi e inven- tari relativi sia alle biblioteche musicali degli elettori di Colonia sia ai fondi archivistici delle realtà musicali e teatrali modenesi dell’Ottocento, oltre agli archivi della Direzione degli spettacoli e della Società Filarmonica Modenese, custoditi presso l’Archivio di Stato e l’Archivio Storico Comunale di Modena. -

THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC of BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented To

Z 2 THE INCIDENTAL MUSIC OF BEETHOVEN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By Theodore J. Albrecht, B. M. E. Denton, Texas May, 1969 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. .................. iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION............... ............. II. EGMONT.................... ......... 0 0 05 Historical Background Egmont: Synopsis Egmont: the Music III. KONIG STEPHAN, DIE RUINEN VON ATHEN, DIE WEIHE DES HAUSES................. .......... 39 Historical Background K*niq Stephan: Synopsis K'nig Stephan: the Music Die Ruinen von Athen: Synopsis Die Ruinen von Athen: the Music Die Weihe des Hauses: the Play and the Music IV. THE LATER PLAYS......................-.-...121 Tarpe.ja: Historical Background Tarpeja: the Music Die gute Nachricht: Historical Background Die gute Nachricht: the Music Leonore Prohaska: Historical Background Leonore Prohaska: the Music Die Ehrenpforten: Historical Background Die Ehrenpforten: the Music Wilhelm Tell: Historical Background Wilhelm Tell: the Music V. CONCLUSION,...................... .......... 143 BIBLIOGRAPHY.....................................-..145 iii LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Egmont, Overture, bars 28-32 . , . 17 2. Egmont, Overture, bars 82-85 . , . 17 3. Overture, bars 295-298 , . , . 18 4. Number 1, bars 1-6 . 19 5. Elgmpnt, Number 1, bars 16-18 . 19 Eqm 20 6. EEqgmont, gmont, Number 1, bars 30-37 . Egmont, 7. Number 1, bars 87-91 . 20 Egmont,Eqm 8. Number 2, bars 1-4 . 21 Egmon t, 9. Number 2, bars 9-12. 22 Egmont,, 10. Number 2, bars 27-29 . 22 23 11. Eqmont, Number 2, bar 32 . Egmont, 12. Number 2, bars 71-75 . 23 Egmont,, 13.