Rule of Law Under Multiparty Democracy in Tanzania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamhuri Ya Muungano Wa Tanzania Bunge La Tanzania

JAMHURI YA MUUNGANO WA TANZANIA BUNGE LA TANZANIA MKUTANO WA KUMI NA SITA NA KUMI NA SABA YATOKANAYO NA KIKAO CHA KUMI NA NNE (DAILY SUMMARY RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS) 21 NOVEMBA, 2014 MKUTANO WA KUMI NA SITA NA KUMI SABA KIKAO CHA KUMI NA NNE – 21 NOVEMBA, 2014 I. DUA Mwenyekiti wa Bunge Mhe. Mussa Azzan Zungu alisoma Dua saa 3.00 Asubuhi na kuliongoza Bunge. MAKATIBU MEZANI – i. Ndg. Asia Minja ii. Ndg. Joshua Chamwela II. MASWALI: Maswali yafuatayo yaliulizwa na wabunge:- 1. OFISI YA WAZIRI MKUU Swali Na. 161 – Mhe. Betty Eliezer Machangu [KNY: Mhe. Dkt. Cyril Chami] Nyongeza i. Mhe. Betty E. Machangu, mb ii. Mhe. Michael Lekule Laizer, mb iii. Mhe. Prof. Peter Msolla, mb Swali Na. 162 - Mhe. Richard Mganga Ndassa, mb Nyongeza (i) Mhe Richard Mganga Ndassa, mb Swali Na. 163 - Mhe. Anne Kilango Malecela, mb Nyongeza : i. Mhe. Anne Kilango Malecela, mb ii. Mhe. John John Mnyika, mb iii. Mhe. Mariam Nassor Kisangi iv. Mhe. Iddi Mohammed Azzan, mb 2 2. OFISI YA RAIS (UTUMISHI) Swali Na. 164 – Mhe. Ritta Enespher Kabati, mb Nyongeza i. Mhe. Ritta Enespher Kabati, mb ii. Mhe. Vita Rashid Kawawa, mb iii. Mhe. Mch. Reter Msingwa, mb 3. WIZARA YA UJENZI Swali Na. 165 – Mhe. Betty Eliezer Machangu, mb Nyongeza :- i. Mhe. Betty Eliezer Machangu, mb ii. Mhe. Halima James Mdee, mb iii. Mhe. Maryam Salum Msabaha, mb Swali Na. 166 – Mhe. Peter Simon Msingwa [KNY: Mhe. Joseph O. Mbilinyi] Nyongeza :- i. Mhe. Peter Simon Msigwa, Mb ii. Mhe. Assumpter Nshunju Mshama, Mb iii. Mhe. Dkt. Mary Mwanjelwa 4. -

Tanzanian State

THE PRICE WE PAY TARGETED FOR DISSENT BY THE TANZANIAN STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2019 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: © Amnesty International (Illustration: Victor Ndula) (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2019 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 56/0301/2019 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 METHODOLOGY 8 1. BACKGROUND 9 2. REPRESSION OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND INFORMATION 11 2.1 REPRESSIVE MEDIA LAW 11 2.2 FAILURE TO IMPLEMENT EAST AFRICAN COURT OF JUSTICE RULINGS 17 2.3 CURBING ONLINE EXPRESSION, CRIMINALIZATION AND ARBITRARY REGULATION 18 2.3.1 ENFORCEMENT OF THE CYBERCRIMES ACT 20 2.3.2 REGULATING BLOGGING 21 2.3.3 CYBERCAFÉ SURVEILLANCE 22 3. EXCESSIVE INTERFERENCE WITH FACT-CHECKING OFFICIAL STATISTICS 25 4. -

Tanzania Human Rights Report 2008

Legal and Human Rights Centre Tanzania Human Rights Report 2008: Progress through Human Rights Funded By; Embassy of Finland Embassy of Norway Embassy of Sweden Ford Foundation Oxfam-Novib Trocaire Foundation for Civil Society i Tanzania Human Rights Report 2008 Editorial Board Francis Kiwanga (Adv.) Helen Kijo-Bisimba Prof. Chris Maina Peter Richard Shilamba Harold Sungusia Rodrick Maro Felista Mauya Researchers Godfrey Mpandikizi Stephen Axwesso Laetitia Petro Writers Clarence Kipobota Sarah Louw Publisher Legal and Human Rights Centre LHRC, April 2009 ISBN: 978-9987-432-74-5 ii Acknowledgements We would like to recognize the immense contribution of several individuals, institutions, governmental departments, and non-governmental organisations. The information they provided to us was invaluable to the preparation of this report. We are also grateful for the great work done by LHRC employees Laetitia Petro, Richard Shilamba, Godfrey Mpandikizi, Stephen Axwesso, Mashauri Jeremiah, Ally Mwashongo, Abuu Adballah and Charles Luther who facilitated the distribution, collection and analysis of information gathered from different areas of Tanzania. Our 131 field human rights monitors and paralegals also played an important role in preparing this report by providing us with current information about the human rights’ situation at the grass roots’ level. We greatly appreciate the assistance we received from the members of the editorial board, who are: Helen Kijo-Bisimba, Francis Kiwanga, Rodrick Maro, Felista Mauya, Professor Chris Maina Peter, and Harold Sungusia for their invaluable input on the content and form of this report. Their contributions helped us to create a better report. We would like to recognize the financial support we received from various partners to prepare and publish this report. -

Majadiliano Ya Bunge ______

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) BUNGE LA TANZANIA ___________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE ___________ MKUTANO WA NANE Kikao cha Thelathini na Tisa – Tarehe 2 AGOSTI, 2012 (Mkutano Ulianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) DUA Spika (Mhe. Anne S. Makinda) Alisoma Dua HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI Hati ifuatayo iliwasilishwa Mezani na:- NAIBU WAZIRI WA USHIRIKIANO WA AFRIKA MASHARIKI: Randama za Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Wizara ya Ushirikiano wa Afrika Mashariki kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2012/2013. SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, naomba mzime vipasa sauti vyenu maana naona vinaingiliana. Ahsante Mheshimiwa Naibu Waziri, tunaingia hatua inayofuata. MASWALI NA MAJIBU SPIKA: Leo ni siku ya Alhamisi lakini tulishatoa taarifa kwamba Waziri Mkuu yuko safarini kwa hiyo kama kawaida hatutakuwa na kipindi cha maswali hayo. Maswali ya kawaida yapo machache na atakayeuliza swali la kwanza ni Mheshimiwa Vita R. M. Kawawa. Na. 310 Fedha za Uendeshaji Shule za Msingi MHE. VITA R. M. KAWAWA aliuliza:- Kumekuwa na makato ya fedha za uendeshaji wa Shule za Msingi - Capitation bila taarifa hali inayofanya Walimu kuwa na hali ngumu ya uendeshaji wa shule hizo. Je, Serikali ina mipango gani ya kuhakikisha kuwa, fedha za Capitation zinatoloewa kama ilivyotarajiwa ili kupunguza matatizo wanayopata wazazi wa wanafunzi kwa kuchangia gharama za uendeshaji shule? NAIBU WAZIRI, OFISI YA WAZIRI MKUU, TAWALA ZA MIKOA NA SERIKALI ZA MITAA (ELIMU) alijibu:- Mheshimiwa Spika, kwa niaba ya Mheshimiwa Waziri Mkuu, naomba kujibu swali la Mheshimiwa Vita Rashid Kawawa, Mbunge wa Namtumbo, kama ifuatavyo:- Mheshimiwa Spika, Serikali kupitia Mpango wa Maendeleo ya Elimu ya Msingi (MMEM) imepanga kila mwanafunzi wa Shule ya Msingi kupata shilingi 10,000 kama fedha za uendeshaji wa shule (Capitation Grant) kwa mwaka. -

Hii Ni Nakala Ya Mtandao (Online Document)

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE _____________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA SITA ______________ Kikao cha Thelathini na Tisa – Tarehe 27 Julai, 2009) (Kikao Kilianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) DUA Spika (Mhe. Samuel J. Sitta) Alisoma Dua MASWALI NA MAJIBU SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, kabla sijamwita anayeuliza swali la kwanza, karibuni tena baada ya mapumziko ya weekend, nadhani mna nguvu ya kutosha kwa ajili ya shughuli za wiki hii ya mwisho ya Bunge hili la 16. Swali la kwanza linaelekezwa Ofisi ya Waziri Mkuu na linauliza na Mheshimiwa Shoka, kwa niaba yake Mheshimiwa Khalifa. Na.281 Kiwanja kwa Ajili ya Kujenga Ofisi ya Tume ya Kudhibiti UKIMWI MHE KHALIFA SULEIMAN KHALIFA (K.n.y. MHE. SHOKA KHAMIS JUMA) aliuliza:- Kwa kuwa Tume ya Taifa ya Kudhibiti UKIMWI inakabiliwa na changamoto ya ufinyu wa Ofisi; na kwa kuwa Tume hiyo imepata fedha kutoka DANIDA kwa ajili ya kujenga jengo la Ofisi lakini inakabiliwa na tatizo kubwa la upatikanaji wa kiwanja:- Je, Serikali itasaidia vipi Tume hiyo kupata kiwanja cha kujenga Ofisi? WAZIRI WA NCHI, OFISI YA WAZIRI MKUU – SERA, URATIBU NA BUNGE alijibu:- Mheshimiwa Spika, kwa niaba ya Mheshimiwa Waziri Mkuu, napenda kujibu swali la Mheshimiwa Shoka Khamis Juma, Mbunge wa Micheweni kama ifuatavyo:- Mheshimiwa Spika, tatizo la kiwanja cha kujenga Ofisi za TACAIDS limepatiwa ufumbuzi na ofisi yangu imewaonesha Maafisa wa DANIDA kiwanja hicho Ijumaa tarehe 17 Julai, 2009. Kiwanja hicho kipo Mtaa wa Luthuli Na. 73, Dar es Salaam ama kwa lugha nyingine Makutano ya Mtaa wa Samora na Luthuli. MHE. KHALIFA SULEIMAN KHALIFA: Mheshimiwa Spika, nakushukuru. Pamoja na majibu mazuri sana ya Mheshimiwa Waziri, naomba kumuuliza swali moja la nyongeza. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex DPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Accountability and Clientelism in Dominant Party Politics: The Case of a Constituency Development Fund in Tanzania Machiko Tsubura Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Development Studies University of Sussex January 2014 - ii - I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: ……………………………………… - iii - UNIVERSITY OF SUSSEX MACHIKO TSUBURA DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES ACCOUNTABILITY AND CLIENTELISM IN DOMINANT PARTY POLITICS: THE CASE OF A CONSTITUENCY DEVELOPMENT FUND IN TANZANIA SUMMARY This thesis examines the shifting nature of accountability and clientelism in dominant party politics in Tanzania through the analysis of the introduction of a Constituency Development Fund (CDF) in 2009. A CDF is a distinctive mechanism that channels a specific portion of the government budget to the constituencies of Members of Parliament (MPs) to finance local small-scale development projects which are primarily selected by MPs. -

Hii Ni Nakala Ya Mtandao (Online Document)

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) BUNGE LA TANZANIA ____________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE ___________ MKUTANO WA NNE Kikao cha Ishirini na Nne – Tarehe 18 Julai, 2006 (Mkutano Ulianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) D U A Spika (Mhe. Samuel J. Sitta) Alisoma Dua MASWALI NA MAJIBU SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, kabla sijamwita muuliza swali la kwanza nina matangazo kuhusu wageni, kwanza wale vijana wanafunzi kutoka shule ya sekondari, naona tangazo halisomeki vizuri, naomba tu wanafunzi na walimu msimame ili Waheshimiwa Wabunge waweze kuwatambua. Tunafurahi sana walimu na wanafunzi wa shule zetu za hapa nchini Tanzania mnapokuja hapa Bungeni kujionea wenyewe demokrasia ya nchi yetu inavyofanya kazi. Karibuni sana. Wapo Makatibu 26 wa UWT, ambao wamekuja kwenye Semina ya Utetezi na Ushawishi kwa Harakati za Wanawake inayofanyika Dodoma CCT wale pale mkono wangu wakulia karibuni sana kina mama tunawatakia mema katika semina yenu, ili ilete mafanikio na ipige hatua mbele katika kumkomboa mwanamke wa Tanzania, ahsanteni sana. Hawa ni wageni ambao tumetaarifiwa na Mheshimiwa Shamsa Selengia Mwangunga, Naibu Waziri wa Maji. Wageni wengine nitawatamka kadri nitakavyopata taarifa, kwa sababu wamechelewa kuleta taarifa. Na. 223 Barabara Toka KIA – Mererani MHE. DORA H. MUSHI aliuliza:- Kwa kuwa, Mererani ni Controlled Area na ipo kwenye mpango wa Special Economic Zone na kwa kuwa Tanzanite ni madini pekee duniani yanayochimbwa huko Mererani na inajulikana kote ulimwenguni kutokana na madini hayo, lakini barabara inayotoka KIA kwenda Mererani ni mbaya sana -

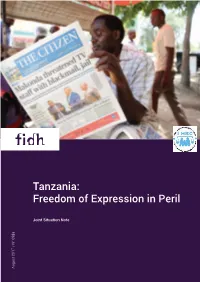

Tanzania: Freedom of Expression in Peril

Tanzania: Freedom of Expression in Peril Joint Situation Note August 2017 / N° 698a August Cover photo: A man reads on March 23, 2017 in Arusha, northern Tanzania, the local English-written daily newspaper «The Citizen», whose front title refers to the sacking of Tanzanian information Minister after he criticised an ally of the president. Tanzania’s President, aka «The Bulldozer» sacked his Minister for Information, Culture and Sports, after he criticised an ally of the president: the Dar es Salaam Regional Commissioner who had stormed into a television station accompanied by armed men. © STRINGER / AFP FIDH and LHRC Joint Situation Note – August 1, 2017 - 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..........................................................................................................................2 I. Dissenting voices have become targets of the authorities..........................................5 II. Human Rights Defenders and ordinary citizens are also in the sights of the authorities...........................................................................................................................10 Recommendations.............................................................................................................12 Annex I – Analysis: Tools for repression: the Media Services Act and the Cybercrimes Act.................................................................................................................13 Annex II – List of journalists and human rights defenders harassed..........................17 -

Tanzania Human Rights Report 2016

Tanzania Human Rights Report 2016 LEGAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS CENTRE & ZANZIBAR LEGAL SERVICES CENTRE NOT FOR SALE Tanzania Human Rights Report - 2016 Mainland and Zanzibar - i - Tanzania Human Rights Report 2016 Part One: Tanzania Mainland - Legal and Human Rights Centre (LHRC) Part Two: Zanzibar - Zanzibar Legal Services Centre (ZLSC) - ii - Tanzania Human Rights Report 2016 Publishers Legal and Human Rights Centre Justice Lugakingira House, Kijitonyama P. O. Box 75254, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Tel: +255222773038/48, Fax: +255222773037 Email: [email protected] Website: www.humanrights.or.tz & Zanzibar Legal Services Centre P. O. Box 3360, Zanzibar, Tanzania Tel: +2552422384 Fax: +255242234495 Email: [email protected] Website: www.zlsc.or.tz Partners The Embassy of Sweden The Embassy of Norway Oxfam Rosa Luxemburg UN Women Open Society Initiatives for Eastern Africa Design & Layout Albert Rodrick Maro Munyetti ISBN: 978-9987-740-30-7 © LHRC & ZLSC 2017 - iii - Tanzania Human Rights Report 2016 Editorial Board - Part One Dr. Helen Kijo-Bisimba Adv. Imelda Urio Ms. Felista Mauya Adv. Anna Henga Researchers/Writers Paul Mikongoti Fundikila Wazambi - iv - Tanzania Human Rights Report 2016 About LHRC The Legal and Human Rights Centre (LHRC) is a private, autonomous, voluntary non- Governmental, non-partisan and non-profit sharing organization envisioning a just and equitable society. It has a mission of empowering the people of Tanzania, so as to promote, reinforce and safeguard human rights and good governance in the country. The broad objective is to create legal and human rights awareness among the public and in particular the underprivileged section of the society through legal and civic education, advocacy linked with legal aid provision, research and human rights monitoring. -

Media Watch October, 2020

March/April, 2012 Waliomeremeta Issue No. 197 October, 2020 EJAT 2019 The overall winners News News News New faces on Guide on MCT gets another MCT Governing Demographic Clean Audit Board Dividend Certificate Page 5 Page 16 Page 25 MCT, WINNER OF 2003 IPI FREE MEDIA PIONEER EDITORIAL AWARD Flexibility, freedom crucial for media s the country was headed to the general election on October 28, 2020 media coverage for all parties and contenders if anything was not equitable. There was a section of the media which covered Athe ruling party through and through, another section covered major opposition on and off. The smaller parties were somehow covered during the initial stages of the electoral campaigns but as the days got close to the polling day they were relegated to obscurity. The initial impression was that the media would strive to provide equitable coverage but it appeared that those parties with political muscle were having the lion’s share. Headlines of mainstream media and main items of Editorial Board broadcast media were full of pledges mainly of the ruling Kajubi Mukajanga party with the other parties mainly covered on social media MCT and were only given prominence in mainstream media in the EXECUTIVE SECRETARY event of intra-party bickering. Given the operational conditions where some media outlets were suspended on claims of flouting regulations David Mbulumi especially related to election coverage, the extra zeal to be PROGRAMME MANAGER careful coupled with a degree of fear resulted in self-censorship. Hamis Mzee It is unfortunate that the media had to operate in this EDITOR situation which was not a leveled playing field. -

Jarida La Wizara Ya Habari Utamaduni Sanaa Na Michezo Uk. 03 Uk. 01

Jarida la Wizara ya Habari Utamaduni Sanaa na Michezo TOLEO 001 LA MTANDAONI OKTOBA, 2017 NDANI Uk. TANZANIA kuwa Mwenyeji Tamasha la 01 JAMAFEST 2019 Uk. Mhe. Juliana Shonza Naibu Waziri Mpya wa 03 Wizara ya Habari Utamaduni Sanaa na Michezo www.habari.go.tz Jarida la Wizara ya Habari Utamaduni Sanaa na Michezo DAWATI LA UHARIRI MSANIFU JARIDA Benedict J. Liwenga WAANDISHI Lorietha Laurence Anitha Jonas Genofeva Matemu Shamimu Nyaki Eleuteri Mangi WAANDAAJI Jarida hili limetolewa na Wizara ya Habari, Utamaduni, Sanaa na Michezo Kitengo cha Mawasiliano Serikalini Jengo la LAPF Mtaa wa Makole Uhindini S.L.P 25 DODOMA-TANZANIA Simu : 026-2322129 Faksi : 026-2322128 Barua Pepe:[email protected] Tovuti: www.habari.go.tz i Jarida la Wizara ya Habari Utamaduni Sanaa na Michezo YALIYOMO HABARI KURASA Tanzania iko tayari kuwa Mwenyeji Tamasha la JAMAFEST 2019 ..................................................1 Mhe. Juliana Shonza ateuliwa kuwa Naibu Waziri wa Habari .........................................................3 Majadiliano ya Kanuni za Maudhui ya Utangazaji na Mitandao ya Kijamii ....................................5 Tamasha la Sanaa na Utamaduni la Kimataifa Bagamoyo ..............................................................7 Mkandarasi Mpya wa Utoaji Tiketi Uwanja wa Taifa-Dar es Salaam................................................9 Tamasha la Utamaduni Tukuyu-Mbeya ............................................................................................11 Matumizi ya Kiswahili Fasaha kwa Watangazaji .............................................................................13 -

Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 106 Sept - Dec 2013

Tanzanian Affairs Text 1 Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 106 Sept - Dec 2013 The Race for the State House President Obama’s Visit Surprises in Draft Constitution Tanzania in a Turbulent World Shangaa - Art Surprising the US Newspaper cover featuring twelve people said to be eying the Presidency. cover photo: Shirt celebrating the visit of President Obama to Tanzania. New cover design - we are trying a new printer who offers full colour. Comments welcome, and please send photos for future covers to [email protected] David Brewin: THE RACE FOR STATE HOUSE Americans usually start campaigning for the next election contest almost immediately after the completion of the previous one. Tanzania seems to be moving in the same direction. Although the elections are not due until late 2015, those aspirants who are considering standing for the top job are beginning to quietly mobilise their support. Speculation is now rife in political circles on the issue of who will succeed President Kikwete. Unlike some of his opposite numbers in other states, notably Zimbabwe, he is expected to comply with the law and retire at the end of his second term as all his predecessors have done. A number of prominent figures are expected to compete in the elections. One factor which could become crucial is a long established ‘under- standing’ that, if the president is a Muslim, as is President Kikwete, his successor should be a Christian. President Nyerere was a Catholic, former President Mwinyi is a Muslim and President Mkapa is also a Catholic. As both the Christian presidents have been Catholics the large Protestant community might be wondering when its time will come.