Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

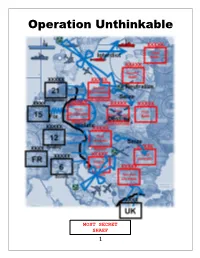

Operation Unthinkable

Operation Unthinkable MOST SECRET SHAEF 1 Mountaineer Game Design by Bob Hatcher I Setting The Game Map & Setup Page 3 Turn Sequence Overview Page 5 Victory Conditions Page 5 II Game Characteristics Geography and Economics Page 6 Allied Forces Page 7 Soviet Forces Page 7 Neutrals Page 8 Units Page 9 III Detailed Sequence of Events Page 11 IV Advanced Rules Page 14 V Parts list Page 16 VI Statistics Page 17 2 I FIGHTING OPERATION UNTHINKABLE At the end of May 1945, it is highly doubtful the Soviet Government is going to allow democratic processes in the countries they occupy. As Prime Minister Churchill feared, it appears the Russians are not going to honor the agreements made between Allies concerning the future of Central and Southern Europe. To impose the will of the United States, The British Empire, and their Allies, the Joint Planning Staff draws up plans for Operation Unthinkable, a plan completely dependent on strategic surprise and the support of other European powers, including those they liberate. Outnumbered 2 to 1 in men and materiel, the Allies will need every advantage in the opening offensive in a war that many thought was over for Europe. D Day is set for 1 July 1945… The Game Map & Setup The game map is divided into territories color-coded based on original national ownership. Allied territory is green and Soviet red. Large city areas are circular and may comprise more than one zone. Territories have a number in each area that indicates their value. There is a timeline chart for tracking turns and events, a chart for national morale, a chart for tracking the formation of NATO, and a chart for random events. -

H-Diplo Roundtables, Vol. XIV, No. 8

2012 H-Diplo Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse Roundtable Web/Production Editor: George Fujii H-Diplo Roundtable Review www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Commissioned for H-Diplo by Thomas Maddux Volume XIV, No. 8 (2012) Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State 12 November 2012 University, Northridge Frank Costigliola. Roosevelt's Lost Alliances: How Personal Politics Helped Start the Cold War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012. ISBN: 9780691121291 (cloth, $35.00); 9781400839520 (eBook, $35.00). Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XIV-8.pdf Contents Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University Northridge............................... 2 Review by Michaela Hoenicke Moore, University of Iowa ....................................................... 8 Review by Michael Holzman, Independent Scholar ............................................................... 15 Review by J Simon Rofe, SOAS, University of London ............................................................ 18 Review by David F. Schmitz, Whitman College ....................................................................... 21 Review by Michael Sherry, Northwestern University ............................................................. 25 Review by Katherine A. S. Sibley, Saint Joseph’s University ................................................... 29 Author’s Response by Frank Costigliola, University of Connecticut ....................................... 33 Copyright © 2012 H-Net: Humanities and -

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: a Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: A Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944 ARGYRIOS MAMARELIS Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy The European Institute London School of Economics and Political Science 2003 i UMI Number: U613346 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613346 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 9995 / 0/ -hoZ2 d X Abstract This thesis addresses a neglected dimension of Greece under German and Italian occupation and on the eve of civil war. Its contribution to the historiography of the period stems from the fact that it constitutes the first academic study of the third largest resistance organisation in Greece, the 5/42 regiment of evzones. The study of this national resistance organisation can thus extend our knowledge of the Greek resistance effort, the political relations between the main resistance groups, the conditions that led to the civil war and the domestic relevance of British policies. -

Why Did Stalin Not Support a Quick Victory for the Korean People's Army? Stalin's Unspoken Global Security Strategy for the Korean War | 81

Why Did Stalin Not Support a Quick Victory for the Korean People’s Army? Stalin’s Unspoken Global Security Strategy for the Korean War Youngjun Kim In this paper, I argue that Stalin maintained a maximum gain/minimum risk security strategy during the Korean War. For the first time, I challenge a com- mon misconception that the Korean People’s Army of North Korea copied and followed the Soviet Army’s operational strategy during the war. I question why the KPA did not follow the Soviet Army’s operational concept in guranteeing a quick victory, and why the Kremlin and Soviet military advisors kept silent during the initial stage of the war. Because the KPA did not follow the Soviet Army’s operational strategy initially, the United Nations forces were able to arrive in Pusan, extending the war. Why didn’t Stalin want a quick victory? Did Stalin want bigger benefits than a quick victory on the Korean Peninsula by delaying the war and distracting the enemy? By examining the KPA’s perfor- mance according to the Soviet Army’s operational concept, I argue that Stalin wanted to use the Korean War as a useful card in his global struggle against the United States. He wanted to lower the risk of war in the European theater because Europe was more strategically significant than Northeast Asia. The memory of Nazi Germany’s invasion was still fresh in Stalin’s mind at the outbreak of the Korean War. Throughout the war, Stalin’s top priority was the national interests of the Soviet Union, and he did not take into account the costs to allies China and North Korea. -

Iron Curtain ©2020

The Gamers, Inc. Standard Combat Series: Iron Curtain ©2020. Multi-Man Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Series Designer: Dean Essig Game Designer & Research Expert: Carl Fung 1.0 Introduction Post World War II Europe was left with an East-West chasm that Game Development: Dean Essig Winston Churchill dramatically dubbed the Iron Curtain. The pos- Editing: Dave Demko, Rusty Witek turing of that potential struggle centered on the heart of Europe VASSAL Module: Jim Pyle until the fall of the Berlin Wall radically altered the status quo in Playtesting: Dave Demko, Ric van Dyke, John Essig, Lee Forester, 1989. Brian Jarvis, Phil Jones, Hans Kishel, Don McIntosh, John Rainey, Allan Rothberg, Chip Saltsman, Mike Solli, James Sterrett, Guy Iron Curtain is an SCS game covering potential open conflicts Wilde between the East and West from 1945 to 1989. Scenarios at multi- ple times illustrate both side’s changing forces and doctrine. Special Thanks: Pete Belli, Thomas Frohnhoefer, Mike Reed, Fred Regardless of the time frame, the war is postulated to be a very Thomas, and Walter Zaagman short period (about a month) of hyper-intensive combat, after Page Item which (beyond the scope of the game) the powers involved 1 1.0 Introduction resolve to end the struggle before it escalates and there are no 2 Run Up & War Turn Sequences of Play winners. The player’s goal is to have the advantage at the peace 3 2.0 Units & Displays table. 5 3.0 Map and Play Conditions 7 4.0 Scenario Rules The sides are: 5.0 Basics Western Allies or NATO 9 6.0 Run Up 10 7.0 War Turns versus 14 8.0 Victory Soviets or Warsaw Pact (WP) 15 9.0 Optionals 16 Abbreviations The terms are selected based on what was correct for the scenario Designer’s Notes involved, but most rules presented below apply to both time per- 19 Developer’s Notes iods and use ‘NATO’ and ‘Warsaw Pact’ for simplicity. -

International Spy Museum

International Spy Museum Searchable Master Script, includes all sections and areas Area Location, ID, Description Labels, captions, and other explanatory text Area 1 – Museum Lobby M1.0.0.0 ΚΑΤΆΣΚΟΠΟΣ SPY SPION SPIJUN İSPİYON SZPIEG SPIA SPION ESPION ESPÍA ШПИОН Language of Espionage, printed on SCHPION MAJASUSI windows around entrance doors P1.1.0.0 Visitor Mission Statement For Your Eyes Only For Your Eyes Only Entry beyond this point is on a need-to-know basis. Who needs to know? All who would understand the world. All who would glimpse the unseen hands that touch our lives. You will learn the secrets of tradecraft – the tools and techniques that influence battles and sway governments. You will uncover extraordinary stories hidden behind the headlines. You will meet men and women living by their wits, lurking in the shadows of world affairs. More important, however, are the people you will not meet. The most successful spies are the unknown spies who remain undetected. Our task is to judge their craft, not their politics – their skill, not their loyalty. Our mission is to understand these daring professionals and their fallen comrades, to recognize their ingenuity and imagination. Our goal is to see past their maze of mirrors and deception to understand their world of intrigue. Intelligence facts written on glass How old is spying? First record of spying: 1800 BC, clay tablet from Hammurabi regarding his spies. panel on left side of lobby First manual on spy tactics written: Over 2,000 years ago, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. 6 video screens behind glass panel with facts and images. -

Dartmouth Conf Program

The Dartmouth Conference: The First 50 Years 1960—2010 Reminiscing on the Dartmouth Conference by Yevgeny Primakov T THE PEAK OF THE COLD WAR, and facilitating conditions conducive to A the Dartmouth Conference was one of economic interaction. the few diversions from the spirit of hostility The significance of the Dartmouth Confer- available to Soviet and American intellectuals, ence relates to the fact that throughout the who were keen, and able, to explore peace- cold war, no formal Soviet-American contact making initiatives. In fact, the Dartmouth had been consistently maintained, and that participants reported to huge gap was bridged by Moscow and Washington these meetings. on the progress of their The composition of discussion and, from participants was a pri- time to time, were even mary factor in the success instructed to “test the of those meetings, and it water” regarding ideas took some time before the put forward by their gov- negotiating teams were ernments. The Dartmouth shaped the right way. At meetings were also used first, in the early 1970s, to unfetter actions under- the teams had been led taken by the two countries by professionally quali- from a propagandist connotation and present fied citizens. From the Soviet Union, political them in a more genuine perspective. But the experts and researchers working for the Insti- crucial mission for these meetings was to tute of World Economy and International establish areas of concurring interests and to Relations and the Institute of U.S. and Cana- attempt to outline mutually acceptable solutions dian Studies, organizations closely linked to to the most acute problems: nuclear weapons Soviet policymaking circles, played key roles. -

C00175072 Page: 1 of 135 UNCLASSIFIED

C00175072 Page: 1 of 135 UNCLASSIFIED Document 71 CLAS UNCLASSIFIED CLAS UNCLASSIFIED AFSN TB1607133591C FROM FBIS LONDON UK SUBJ TAKEALL-- Comlist: Moscow Consolidated 15 Jul 91 Full Text Superzone of Hessage 1 GLOBAL 2 1 gorbachev 12 jul moscow press conference to soviet and foreign journalists on forthcoming london G-7 meeting. (c/r home 121215, item 3 on 12 jul list) (1.5 min: swahili 121800; brief: enginter 0800 0900 1000 1100 1200 1300 1400 1500 1600 1700 1800 frenchinter 1800 spanish 2100 czech/slovak 1800 polish 1600) 3 2 vitaliy gurov presents highlights from news conference addressed by president gorbachev on forthcoming G-7 summit. (rpt enginter 121510, item 4 on 12 jul list) (5 min: swabili 121800) 4 3 vitaliy gurov on forthcoming G-7 meeting in london. (rpt enginter 141210, item 8 on 14 jul list) (engna 142300 amharic 141600 swabili 141800 jap 141400 beng 1200 hind 1300; anon: spanish 142100) 5 4 canadian radio quotes yevgeniy primakov saying gorbachev will face "social explosion" if he returns from london empty-handed. (brief: rtv 2000) 6 5 primakov stmt at london news conference on ussr economic cooperation with west. (brief: greek 2000) 7 6 zorin video report showing world leaders arriving at lancaster house, voiceover recaps G-7 summit traditional goals, video shows ignatenko supervizing preparations for gorbachev's press conference, head of press center interviewed. (4.5 min: tv 1800) 8 7 account of vitaly ignatenko's 15 jul london press conference, re forthcoming meeting between gorbachev and G-7 leaders, stressing historical significance. (700 text sent: tassr 1319 tasse 1646) 9 8 andrey ptashnikov telephone report pegged to opening of G-7 summit in london, noting that though talks are' officially economic, political issues will be important and may, indeed, predominate, stressing relations with ussr will be among most important topics on agenda, giving factual information on background to talks and program of gorbachev's visit. -

Spring-2003-Part 1-Live

NIEMAN REPORTS THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL.57 NO.1 SPRING 2003 Five Dollars Reporting on Health Investigating Scandal in the Catholic Church Journalists Testifying at War Crimes Tribunals “… to promote and elevate the standards of journalism” —Agnes Wahl Nieman, the benefactor of the Nieman Foundation. Vol. 57 No. 1 NIEMAN REPORTS Spring 2003 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY Publisher Bob Giles Editor Melissa Ludtke Assistant Editor Lois Fiore Editorial Assistant Elizabeth Son Design Editor Deborah Smiley Nieman Reports (USPS #430-650) is published Please address all subscription correspondence to in March, June, September and December One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098 by the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University, and change of address information to One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098. P.O. Box 4951, Manchester, NH 03108. ISSN Number 0028-9817 Telephone: (617) 496-2968 Second-class postage paid E-Mail Address (Business): at Boston, Massachusetts, [email protected] and additional entries. E-Mail Address (Editorial): POSTMASTER: [email protected] Send address changes to Nieman Reports, Internet Address: P.O. Box 4951, www.Nieman.Harvard.edu Manchester, NH 03108. Copyright 2003 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Subcription $20 a year, $35 for two years; add $10 per year for foreign airmail. Single copies $5. Back copies are available from the Nieman office. Vol. 57 No. 1 NIEMAN REPORTS Spring 2003 THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY 5 Reporting on Health 7 Frustrations on the Frontlines of the Health Beat BY ANDREW HOLTZ 10 The Public Health Beat: What Is It? Why Is It Important? BY M.A.J. -

![Pdf?Sequence=1 [In Ukrainian]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8074/pdf-sequence-1-in-ukrainian-4878074.webp)

Pdf?Sequence=1 [In Ukrainian]

МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ ДРОГОБИЦЬКИЙ ДЕРЖАВНИЙ ПЕДАГОГІЧНИЙ УНІВЕРСИТЕТ ІМЕНІ ІВАНА ФРАНКА MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE DROHOBYCH IVAN FRANKO STATE PEDAGOGICAL UNIVERSITY ISSN 2519-058X (Print) ISSN 2664-2735 (Online) СХІДНОЄВРОПЕЙСЬКИЙ ІСТОРИЧНИЙ ВІСНИК EAST EUROPEAN HISTORICAL BULLETIN ВИПУСК 16 ISSUE 16 Дрогобич, 2020 Drohobych, 2020 Рекомендовано до друку Вченою радою Дрогобицького державного педагогічного університету імені Івана Франка (протокол від 28 серпня 2020 року № 12) Наказом Міністерства освіти і науки України збірник включено до КАТЕГОРІЇ «А» Переліку наукових фахових видань України, в яких можуть публікуватися результати дисертаційних робіт на здобуття наукових ступенів доктора і кандидата наук у галузі «ІСТОРИЧНІ НАУКИ» (Наказ МОН України № 358 від 15.03.2019 р., додаток 9). Східноєвропейський історичний вісник / [головний редактор В. Ільницький]. – Дрогобич: Видавничий дім «Гельветика», 2020. – Випуск 16. – 268 с. Збірник розрахований на науковців, викладачів історії, аспірантів, докторантів, студентів й усіх, хто цікавиться історичним минулим. Редакційна колегія не обов’язково поділяє позицію, висловлену авторами у статтях, та не несе відповідальності за достовірність наведених даних і посилань. Головний редактор: Ільницький В. І. – д.іст.н., проф. Відповідальний редактор: Галів М. Д. – д.пед.н., доц. Редакційна колегія: Манвідас Віткунас – д.і.н., доц. (Литва); Вацлав Вєжбєнєц – д.габ. з історії, проф. (Польща); Дюра Гарді – д.філос. з історії, професор (Сербія); Дарко Даровец – д. фі- лос. з історії, проф. (Італія); Дегтярьов С. І. – д.і.н., проф. (Україна); Пол Джозефсон – д. філос. з історії, проф. (США); Сергій Єкельчик – д. філос. з історії, доц. (Канада); Сергій Жук – д.і.н., проф. (США); Саня Златановіч – д.філос. з етнології та антропо- логії, ст. наук. спів.