In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project

The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project JOHN W. MCDONALD Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: June 5, 1997 Copyright 2 3 ADST TABLE OF CONTENTS Background Born in Ko lenz, Germany of U.S. military parents Raised in military bases throughout U.S. University of Illinois Berlin, Germany - OMGUS - Intern Program 1,4.-1,50 1a2 Committee of Allied Control Council Morgenthau Plan Court system Environment Currency reform Berlin Document Center Transition to State Department Allied High Commission Bonn, Germany - Allied High Commission - Secretariat 1,50-1,52 The French Office of Special Representative for Europe General 6illiam Draper Paris, France - Office of the Special Representative for Europe - Staff Secretary 1,52-1,54 U.S. Regional Organization 7USRO8 Cohn and Schine McCarthyism State Department - Staff Secretariat - Glo al Briefing Officer 1,54-1,55 Her ert Hoover, 9r. 9ohn Foster Dulles International Cooperation Administration 1,55-1,5, E:ecutive Secretary to the Administration Glo al development Area recipients P1480 Point Four programs Anti-communism Africa e:perts African e:-colonies The French 1and Grant College Program Ankara, Turkey -CENTO - U.S. Economic Coordinator 1,5,-1,63 Cooperation programs National tensions Environment Shah of Iran AID program Micro2ave projects Country mem ers Cairo, Egypt - Economic Officer 1,63-1,66 Nasser AID program Soviets Environment Surveillance P1480 agreement As2an Dam Family planning United Ara ic Repu lic 7UAR8 National -

Iris Murdoch

Sunday 9th August 2020 www.rmmc.org.uk Facebook: www.facebook.com/groups/tempRMMC/ Last week I shared the first part of the story of Arthur & Ada Salter that had impressed me as I walked the Thames Path. Part Two included today with Part One as reference if you want to re-read! Zoom Church Service Aug 9, 2020 6pm led by Cathy Smith https://astrazeneca.zoom.us/j/99881042054?pwd=UWU3QmE0VkNYNXBMNENLd2dkVmh4QT09 Meeting ID: 998 8104 2054. Password: 562655 0203 481 5237 or 0800 260 5801 7.30pm Monday 10th August The Prayer Course Session 1: Why Pray? https://us02web.zoom.us/j/84151838035?pwd=WFpkZTBjUW9MSW9VL2VMRDBYcU9iUT09 ID: 841 5183 8035 Passcode: 483980. Landline: 0203 051 2874 ‘Prayer is simply paying attention to God, which is a form of love.’ Iris Murdoch Unlike the last course I am thinking of this one being once or twice a month, and with a different aspect of prayer each time it will be easy for people to attend as many sessions as they like and are able. I look for- ward to us learning together. Living Streets and Highways We pray for the living streets in our neighbourhood, where our daily travels begin and end, and our love of God inspires our interactions with our neighbours. In our walks and our rides and our drives and our deliveries, God keep us safe and looking out for others. Somebody during the post-service coffee session on last Sunday's zoom call asked for more de- tails about the Highway Code Consultation. In summary the proposed changes support a heirar- chy of road-users, prioritising people who are most vulnerable to harm, starting with pedestrians, (especially children, older adults and people with disabilities) and stating more clearly how all oth- er road users can reduce the danger they may pose to others. -

![West Lancashire Area (1939)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3606/west-lancashire-area-1939-83606.webp)

West Lancashire Area (1939)]

10 May 2019 [WEST LANCASHIRE AREA (1939)] West Lancashire Area Regular Depots in the Area The South Lancashire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s Volunteers) – Warrington The King’s Regiment (Liverpool) – Seaforth, Liverpool The Cheshire Regiment – Chester The South Staffordshire Regiment – Lichfield The North Staffordshire Regiment (The Prince of Wales’s) – Lichfield Regular Troops in the Area Militia in the Area 12th Anti-Aircraft Depot – Saighton 18th Searchlight Depot – Saighton Territorial Army Troops in the Area th 6 Cavalry Brigade (1) The Cheshire Yeomanry (The Earl of Chester’s) The Staffordshire Yeomanry (Queen’s Own Royal Regiment) rd 23 Army Tank Brigade (2) 40th Royal Tank Regiment 46th Royal Tank Regiment Other Unbrigaded Units th 4 Bn. The Cheshire Regiment (3) th 5 (Earl of Chester’s) Bn. The Cheshire Regiment (4) th 6 Bn. The Cheshire Regiment (5) th 7 Bn. The Cheshire Regiment (6) th 106 Regiment (Lancashire Yeomanry), Royal Horse Artillery (7) (H.Q., 423rd (Lancashire Yeomanry) & 424th (Lancashire Yeomanry) Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery) th 149 Regiment (Lancashire Yeomanry), Royal Horse Artillery (8) (H.Q., 432nd & 433rd Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery) © w w w . B r i t i s h M i l i t a r y H istory.co.uk Page 1 10 May 2019 [WEST LANCASHIRE AREA (1939)] th nd 88 (2 West Lancashire) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (9) (H.Q., 351st (11th West Lancashire) & 352nd (26th West Lancashire) Field Batteries, Royal Artillery) th 137 Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (10) (H.Q., 349th (9th West Lancashire) & 350th (10th West -

DONALD NICOL Donald Macgillivray Nicol 1923–2003

DONALD NICOL Donald MacGillivray Nicol 1923–2003 DONALD MACGILLIVRAY NICOL was born in Portsmouth on 4 February 1923, the son of a Scottish Presbyterian minister. He was always proud of his MacGillivray antecedents (on his mother’s side) and of his family’s connection with Culloden, the site of the Jacobite defeat in 1745, on whose correct pronunciation he would always insist. Despite attending school first in Sheffield and then in London, he retained a slight Scottish accent throughout his life. By the time he left St Paul’s School, already an able classical scholar, it was 1941; the rest of his education would have to wait until after the war. Donald’s letters, which he carefully preserved and ordered with the instinct of an archivist, provide details of the war years.1 In 1942, at the age of nineteen, he was teaching elementary maths, Latin and French to the junior forms at St-Anne’s-on-Sea, Lancashire. He commented to his father that he would be dismissed were it known that he was a conscientious objector. By November of that year he had entered a Friends’ Ambulance 1 The bulk of his letters are to his father (1942–6) and to his future wife (1949–50). Also preserved are the letters of his supervisor, Sir Steven Runciman, over a forty-year period. Other papers are his diaries, for a short period of time in 1944, his notebooks with drawings and plans of churches he studied in Epiros, and his account of his travels on Mount Athos. This material is now in the King’s College London Archives, by courtesy of the Nicol family. -

Inscribed 6 (2).Pdf

Inscribed6 CONTENTS 1 1. AVIATION 33 2. MILITARY 59 3. NAVAL 67 4. ROYALTY, POLITICIANS, AND OTHER PUBLIC FIGURES 180 5. SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 195 6. HIGH LATITUDES, INCLUDING THE POLES 206 7. MOUNTAINEERING 211 8. SPACE EXPLORATION 214 9. GENERAL TRAVEL SECTION 1. AVIATION including books from the libraries of Douglas Bader and “Laddie” Lucas. 1. [AITKEN (Group Captain Sir Max)]. LARIOS (Captain José, Duke of Lerma). Combat over Spain. Memoirs of a Nationalist Fighter Pilot 1936–1939. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. 8vo., cloth, pictorial dust jacket. London, Neville Spearman. nd (1966). £80 A presentation copy, inscribed on the half title page ‘To Group Captain Sir Max AitkenDFC. DSO. Let us pray that the high ideals we fought for, with such fervent enthusiasm and sacrifice, may never be allowed to perish or be forgotten. With my warmest regards. Pepito Lerma. May 1968’. From the dust jacket: ‘“Combat over Spain” is one of the few first-hand accounts of the Spanish Civil War, and is the only one published in England to be written from the Nationalist point of view’. Lerma was a bomber and fighter pilot for the duration of the war, flying 278 missions. Aitken, the son of Lord Beaverbrook, joined the RAFVR in 1935, and flew Blenheims and Hurricanes, shooting down 14 enemy aircraft. Dust jacket just creased at the head and tail of the spine. A formidable Vic formation – Bader, Deere, Malan. 2. [BADER (Group Captain Douglas)]. DEERE (Group Captain Alan C.) DOWDING Air Chief Marshal, Lord), foreword. Nine Lives. Portrait frontispiece, illustrations. First edition. -

Britain and the Greek Civil War, 1944–1949 British Imperialism, Public Opinion and the Coming of the Cold War

Britain and the Greek Civil War, 1944–1949 British Imperialism, Public Opinion and the Coming of the Cold War JOHN SAKKAS Harrassowitz Verlag (Germany, 2013), 149 pp/28 illust. ISBN: 978-3-447-06718-8 The Greek civil war holds a significant place in the history of twentieth-century Europe for many reasons. Firstly, it was Europe’s bloodiest conflict in the second half of the 1940s; secondly, it marked a turning point in the Cold War; and lastly, it showed how Greece had become an ‘apple of discord’ for both American and Soviet involvement in Greek affairs which led to even more complexity in the country’s post-war politics. Yet despite its significance, only a limited number of studies have been carried out on the subject of this era. After the troubled period of the 1950s and 1960s, a time dominated by extreme conservatism, anti-communism and nationalist paroxysms, it was difficult to access material sources and this made it nearly impossible to conduct scholarly research, so that older politically-charged interpretations and accounts went mostly unchallenged. However, in the past two decades a new historiographical current has developed as regards the civil war in Greece and new evaluations and debates have emerged that shed fresh light on conventional supposition. Britain and the Greek Civil War, 1944–1949 draws upon the author’s doctoral dissertation and provides a welcome addition to studies on that period in Greek history. John Sakkas takes up a novel approach that does not focus solely on Greek politics, whether they are national or local, nor does it centre simply on British policy in Greece. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

U DDC Records of the Union 1910-1974 of Democratic Control

Hull History Centre: Records of the Union of Democratic Control U DDC Records of the Union 1910-1974 of Democratic Control Historical background: The UDC was established in the first days of the First World War to work for parliamentary control of foreign policy and a moderate peace settlement. There was a belief in some quarters that Britain had been dragged into the war because of secret military agreements with France and Russia. The early leaders of the group initially called the Committee of Democratic Control, were Charles Trevelyan (the only member of the Liberal government to resign over the declaration of war), James Ramsay Macdonald, Arthur Ponsonby, Norman Angell and ED Morel. Morel became the secretary and initial driving force behind what was soon re-named the Union of Democratic Control. The group was formally launched with an open letter to the press in early September 1914. The UDC's stated objectives were: parliamentary control over foreign policy and the prevention of secret diplomacy, a movement for international understanding after the war, and a just peace. A Committee of 18 members was established, including Arthur Henderson, JA Hobson and Bertrand Russell. Operations were initially based at Charles Trevelyan's London home, but offices were quickly acquired off the Strand, and later, on Fleet Street. Running costs were met from subscriptions, plus large donations received from several major Quaker business concerns. In late 1917 the UDC reached its maximum membership of some 10,000 individuals in over 100 branches. By 1918, 300 other groups (mainly co-operatives, trade unions and women's organisations) with 650,000 members were also affiliated to the UDC. -

Red Flag Over Bermondsey - the Ada Salter Story

7.00 pm SATURDAY 5 DECEMBER 2015 RED FLAG OVER BERMONDSEY - THE ADA SALTER STORY Written and performed by Lynn Morris Directed by Dave Morris Where to start with Ada Salter? She was a true radical, campaigner for equal rights, socialist, republican, pacifist, environmentalist, trade union activist and a leading light in the transformation of the Bermondsey slums in the early part of the 20th century. Born into Methodism, she moved to London and became involved with the Bermondsey Settlement. She became a Quaker in 1914. She and her GP husband, Alfred Salter, dedicated their lives to the people of Bermondsey, living and working right in the heart of their community – and having to accept the tragic consequences of their choice. She and her husband were among the founders of the Independent Labour Party in Bermondsey. Ada herself broke through the glass ceiling of her time, becoming both the first woman councillor in London, and then the first woman mayor. Red Flag over Bermondsey explores the private and the public lives of Ada from 1909 until 1922, interwoven with her beloved Ira Sankey hymns and her passion for Handel. Further background about Ada (1866–1942) is to be found at www.quakersintheworld.org The performance lasts 65 minutes without interval. Lynn and Dave Morris are Journeymen theatre and they are committed to performing their work in any venue, theatre or non-theatre. Lynn and David attend Stourbridge Quaker Meeting. Visit the website at: www.journeymentheatre.com for details about the company, current and future productions, and reviews. Contact us at: [email protected] or [email protected] Admission FREE: All profits and donations from Red Flag over Bermondsey will be used to support our work with the Women’s Co-operative of Seir, West Bank, Palestine. -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

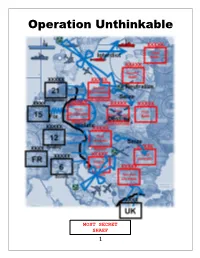

Operation Unthinkable

Operation Unthinkable MOST SECRET SHAEF 1 Mountaineer Game Design by Bob Hatcher I Setting The Game Map & Setup Page 3 Turn Sequence Overview Page 5 Victory Conditions Page 5 II Game Characteristics Geography and Economics Page 6 Allied Forces Page 7 Soviet Forces Page 7 Neutrals Page 8 Units Page 9 III Detailed Sequence of Events Page 11 IV Advanced Rules Page 14 V Parts list Page 16 VI Statistics Page 17 2 I FIGHTING OPERATION UNTHINKABLE At the end of May 1945, it is highly doubtful the Soviet Government is going to allow democratic processes in the countries they occupy. As Prime Minister Churchill feared, it appears the Russians are not going to honor the agreements made between Allies concerning the future of Central and Southern Europe. To impose the will of the United States, The British Empire, and their Allies, the Joint Planning Staff draws up plans for Operation Unthinkable, a plan completely dependent on strategic surprise and the support of other European powers, including those they liberate. Outnumbered 2 to 1 in men and materiel, the Allies will need every advantage in the opening offensive in a war that many thought was over for Europe. D Day is set for 1 July 1945… The Game Map & Setup The game map is divided into territories color-coded based on original national ownership. Allied territory is green and Soviet red. Large city areas are circular and may comprise more than one zone. Territories have a number in each area that indicates their value. There is a timeline chart for tracking turns and events, a chart for national morale, a chart for tracking the formation of NATO, and a chart for random events. -

Europe's Rebirth After the Second World War

Journal of the British Academy, 3, 167–183. DOI 10.5871/jba/003.167 Posted 5 October 2015. © The British Academy 2015 Out of the ashes: Europe’s rebirth after the Second World War, 1945–1949 Raleigh Lecture on History read 2 July 2015 IAN KERSHAW Fellow of the Academy Abstract: This lecture seeks to explain why the Second World War, the most destruc- tive conflict in history, produced such a contrasting outcome to the First. It suggests that the Second World War’s maelstrom of destruction replaced a catastrophic matrix left by the First — of heightened ethnic, border and class conflict underpinned by a deep and prolonged crisis of capitalism — by a completely different matrix: the end of Germany’s great-power ambitions, the purging of the radical Right and widescale ethnic cleansing, the crystallisation of Europe’s division, unprecedented rates of economic growth and the threat of nuclear war. Together, these self-reinforcing components, all rooted in what soon emerged as the Cold War, conditioned what in 1945 had seemed highly improbable: Europe’s rise out of the ashes of the ruined continent to lasting stability, peace and prosperity. Keywords: Cold War, Germany, ethnic cleansing, economic growth, matrix, Europe’s division, radical Right, nuclear war. It is a great honour to deliver this Raleigh Lecture. When invited to do so, I was asked, in the context of the 70th anniversary of the end of the most terrible war in history, to speak on some topic related to the end of the Second World War. As the war recedes into history the recognition has grown that it was the epicentre and determin- ing episode in the 20th century in Europe.