H-Diplo Roundtables, Vol. XIV, No. 8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

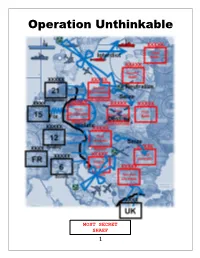

Operation Unthinkable

Operation Unthinkable MOST SECRET SHAEF 1 Mountaineer Game Design by Bob Hatcher I Setting The Game Map & Setup Page 3 Turn Sequence Overview Page 5 Victory Conditions Page 5 II Game Characteristics Geography and Economics Page 6 Allied Forces Page 7 Soviet Forces Page 7 Neutrals Page 8 Units Page 9 III Detailed Sequence of Events Page 11 IV Advanced Rules Page 14 V Parts list Page 16 VI Statistics Page 17 2 I FIGHTING OPERATION UNTHINKABLE At the end of May 1945, it is highly doubtful the Soviet Government is going to allow democratic processes in the countries they occupy. As Prime Minister Churchill feared, it appears the Russians are not going to honor the agreements made between Allies concerning the future of Central and Southern Europe. To impose the will of the United States, The British Empire, and their Allies, the Joint Planning Staff draws up plans for Operation Unthinkable, a plan completely dependent on strategic surprise and the support of other European powers, including those they liberate. Outnumbered 2 to 1 in men and materiel, the Allies will need every advantage in the opening offensive in a war that many thought was over for Europe. D Day is set for 1 July 1945… The Game Map & Setup The game map is divided into territories color-coded based on original national ownership. Allied territory is green and Soviet red. Large city areas are circular and may comprise more than one zone. Territories have a number in each area that indicates their value. There is a timeline chart for tracking turns and events, a chart for national morale, a chart for tracking the formation of NATO, and a chart for random events. -

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: a Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944

The Rise and Fall of the 5/42 Regiment of Evzones: A Study on National Resistance and Civil War in Greece 1941-1944 ARGYRIOS MAMARELIS Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy The European Institute London School of Economics and Political Science 2003 i UMI Number: U613346 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613346 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 9995 / 0/ -hoZ2 d X Abstract This thesis addresses a neglected dimension of Greece under German and Italian occupation and on the eve of civil war. Its contribution to the historiography of the period stems from the fact that it constitutes the first academic study of the third largest resistance organisation in Greece, the 5/42 regiment of evzones. The study of this national resistance organisation can thus extend our knowledge of the Greek resistance effort, the political relations between the main resistance groups, the conditions that led to the civil war and the domestic relevance of British policies. -

Why Did Stalin Not Support a Quick Victory for the Korean People's Army? Stalin's Unspoken Global Security Strategy for the Korean War | 81

Why Did Stalin Not Support a Quick Victory for the Korean People’s Army? Stalin’s Unspoken Global Security Strategy for the Korean War Youngjun Kim In this paper, I argue that Stalin maintained a maximum gain/minimum risk security strategy during the Korean War. For the first time, I challenge a com- mon misconception that the Korean People’s Army of North Korea copied and followed the Soviet Army’s operational strategy during the war. I question why the KPA did not follow the Soviet Army’s operational concept in guranteeing a quick victory, and why the Kremlin and Soviet military advisors kept silent during the initial stage of the war. Because the KPA did not follow the Soviet Army’s operational strategy initially, the United Nations forces were able to arrive in Pusan, extending the war. Why didn’t Stalin want a quick victory? Did Stalin want bigger benefits than a quick victory on the Korean Peninsula by delaying the war and distracting the enemy? By examining the KPA’s perfor- mance according to the Soviet Army’s operational concept, I argue that Stalin wanted to use the Korean War as a useful card in his global struggle against the United States. He wanted to lower the risk of war in the European theater because Europe was more strategically significant than Northeast Asia. The memory of Nazi Germany’s invasion was still fresh in Stalin’s mind at the outbreak of the Korean War. Throughout the war, Stalin’s top priority was the national interests of the Soviet Union, and he did not take into account the costs to allies China and North Korea. -

Iron Curtain ©2020

The Gamers, Inc. Standard Combat Series: Iron Curtain ©2020. Multi-Man Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Series Designer: Dean Essig Game Designer & Research Expert: Carl Fung 1.0 Introduction Post World War II Europe was left with an East-West chasm that Game Development: Dean Essig Winston Churchill dramatically dubbed the Iron Curtain. The pos- Editing: Dave Demko, Rusty Witek turing of that potential struggle centered on the heart of Europe VASSAL Module: Jim Pyle until the fall of the Berlin Wall radically altered the status quo in Playtesting: Dave Demko, Ric van Dyke, John Essig, Lee Forester, 1989. Brian Jarvis, Phil Jones, Hans Kishel, Don McIntosh, John Rainey, Allan Rothberg, Chip Saltsman, Mike Solli, James Sterrett, Guy Iron Curtain is an SCS game covering potential open conflicts Wilde between the East and West from 1945 to 1989. Scenarios at multi- ple times illustrate both side’s changing forces and doctrine. Special Thanks: Pete Belli, Thomas Frohnhoefer, Mike Reed, Fred Regardless of the time frame, the war is postulated to be a very Thomas, and Walter Zaagman short period (about a month) of hyper-intensive combat, after Page Item which (beyond the scope of the game) the powers involved 1 1.0 Introduction resolve to end the struggle before it escalates and there are no 2 Run Up & War Turn Sequences of Play winners. The player’s goal is to have the advantage at the peace 3 2.0 Units & Displays table. 5 3.0 Map and Play Conditions 7 4.0 Scenario Rules The sides are: 5.0 Basics Western Allies or NATO 9 6.0 Run Up 10 7.0 War Turns versus 14 8.0 Victory Soviets or Warsaw Pact (WP) 15 9.0 Optionals 16 Abbreviations The terms are selected based on what was correct for the scenario Designer’s Notes involved, but most rules presented below apply to both time per- 19 Developer’s Notes iods and use ‘NATO’ and ‘Warsaw Pact’ for simplicity. -

Bruno Kamiński

Fear Management. Foreign threats in the postwar Polish propaganda – the influence and the reception of the communist media (1944 -1956) Bruno Kamiński Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 14 June 2016 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Fear Management. Foreign threats in the postwar Polish propaganda – the influence and the reception of the communist media (1944 -1956) Bruno Kamiński Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Prof. Pavel Kolář (EUI) - Supervisor Prof. Alexander Etkind (EUI) Prof. Anita Prażmowska (London School Of Economics) Prof. Dariusz Stola (University of Warsaw and Polish Academy of Science) © Bruno Kamiński, 2016 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I <Bruno Kamiński> certify that I am the author of the work < Fear Management. Foreign threats in the postwar Polish propaganda – the influence and the reception of the communist media (1944 -1956)> I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. -

Churchill's Dark Side

Degree Programme: Politics with a Minor (EUUB03) Churchill’s Dark Side To What Extent did Winston Churchill have a Dark Side from 1942-1945? Abstract 1 Winston Churchill is considered to be ‘one of history's greatest leaders; without his 1 leadership, the outcome of World War II may have been completely different’0F . This received view has dominated research, subsequently causing the suppression of Churchill’s critical historical revisionist perspective. This dissertation will explore the boundaries of the revisionist perspective, whilst the aim is, simultaneously, to assess and explain the extent Churchill had a ‘dark side’ from 1942-1945. To discover this dark side, frameworks will be applied, in addition to rational and irrational choice theory. Here, as part of the review, the validity of rational choice theory will be questioned; namely, are all actions rational? Hence this research will construct another viewpoint, that is irrational choice theory. Irrational choice theory stipulates that when the rational self-utility maximisation calculation is not completed correctly, actions can be labelled as irrational. Specifically, the evaluation of the theories will determine the legitimacy of Churchill’s dark actions. Additionally, the dark side will be 2 3 assessed utilising frameworks taken from Furnham et al1F , Hogan2F and Paulhus & 4 Williams’s dark triad3F ; these bring depth when analysing the presence of a dark side; here, the Bengal Famine (1943), Percentage Agreement (1944) and Operation 1 Matthew Gibson and Robert J. Weber, "Applying Leadership Qualities Of Great People To Your Department: Sir Winston Churchill", Hospital Pharmacy 50, no. 1 (2015): 78, doi:10.1310/hpj5001-78. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Schlesinger, A. ‘Origins of the Cold War’, pp. 22–52. 2. Gaddis, J. L. (1997) We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History (Oxford: Clarendon), p. 292. 3. Feis, H. (1970) From Trust to Terror: The Onset of the Cold War, 1945–50 (London: Blond), p. 5. 4. Woods, R. and Jones, H. (1991) The Dawning of the Cold War (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press), p. xii. 5. Ulam, A. (1973) Expansion and Coexistence (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston), pp. 12–30. 6. Schlesinger, ‘Origins of the Cold War’, pp. 22–52. 7. Gardner, L. (1970) Architects of Illusion: Men and Ideas in American Foreign Policy (Chicago, IL: Quadrangle Books), p. 319. Horowitz argues that con- tainment policies are to be understood as policies for containing social revolution rather than as national expansion. See Horowitz, D. (ed.) (1967) Containment and Revolution: Western Policy Towards Social Revolution: 1917 to Vietnam (London: Blond), p. 53. 8. Williams, W. A. (1968) The Tragedy of American Diplomacy, rev. edn (New York: Norton), p. 15. 9. Lundestad, G. (1978) The American Non-Policy Towards Eastern Europe 1943– 1947 (Tromsö, Oslo and Bergen: Universiteitsforlaget), p. 424. 10. Kolko, G. (1990) Politics of War (New York: Pantheon), pp. 621–2. 11. Kolko, G. and Kolko, J. (1972) The Limits of Power: The World and U.S. Foreign Policy, 1945–1954 (New York: Harper and Row), p. 709. 12. Paterson, T. (1973) Soviet-American Confrontation: Postwar Reconstruction and the Origins of the Cold War (Baltimore, MD and London: Johns Hopkins University Press), pp. 262–4. -

The Origins and Development of the Truman Doctrine

A Reluctant Call to Arms: The Origins and Development of the Truman Doctrine By: Samuel C. LaSala A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY University of Central Oklahoma Spring 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………i Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………..ii Chapter One Historiography and Methodology…………..………………………..………1 Chapter Two From Allies to Adversaries: The Origins of the Cold War………………….22 Chapter Three A Failure to Communicate: Truman’s Public Statements and American Foreign Policy in 1946…….………………………………………………...59 Chapter Four Overstating His Case: Proclaiming the Truman Doctrine……………………86 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………120 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………………...127 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….136 Acknowledgements No endeavor worth taking could be achieved without the support of one’s family, friends, and mentors. With this in mind, I want to thank the University of Central Oklahoma’s faculty for helping me become a better student. Their classes have deepened my fascination and love for history. I especially want to thank Dr. Xiaobing Li, Dr. Patricia Loughlin, and Dr. Jeffrey Plaks for their guidance, insights, and valuable feedback. Their participation on my thesis committee is greatly appreciated. I also want to thank my friends, who not only tolerated my many musings and rants, but also provided much needed morale boosts along the way. I want to express my gratitude to my family without whom none of this would be possible. To my Mom, Dad, and brother: thank you for sparking my love of history so very long ago. To my children: thank you for being patient with your Dad and just, in general, being awesome kids. -

Development of the Ussr Chapter 4

DEVELOPMENT OF THE USSR CHAPTER 4 COLD WAR RELATIONS, 1945-91 Why did relations between the USSR and the USA change between 1945 and 1991? The Cold War lasted from the end of the Second World War to the fall of communism in 1990. It was a time of intense political, economic, military and ideological rivalry between the USA and her democratic allies in the West, and the USSR and its satellite states. The development of nuclear weapons by both sides meant that if a war broke out, it would be a “hot war” which would lead to global destruction. Instead, both sides resorted to a “cold war” or a war of nerves that did not lead to direct confrontation and actual fighting. CAUSES OF POST-WAR TENSIONS Who was to blame for the Cold War? This is up for debate. The commonly held view until the 1960s was that Stalin was principally responsible as a result of his expansionist programme. In the 1960s, it could be argued that the blame had shifted to the USA who had become the aggressor with her involvement in the Vietnam War, along with the commitment to counter the threat of Soviet world domination. It might be politic to place the blame on both superpowers and view the Cold War as a clash of ideologies during a period of heightened fear and mistrust coupled with misperceptions and poor policy making. Stalin had become allies with the Western powers through necessity rather than desire. The single factor that brought the “Big Three” (Britain, the USA and the USSR) together was a collective need to defeat Nazi Germany. -

Solitaire : Operation Unthinkable: Churchill's World War III

Solitaire : Operation Unthinkable: Churchill's World War III Operation Unthinkable: Churchill's World War III Operation Unthinkable, designed by Ty Bomba, allows one or two players to explore the possible outcomes inherent in the campaign that would’ve resulted had Winston Churchill’s plan for starting World War III in July 1945 been put into effect. Rating: Not Rated Yet Price Price £59.95 Ask a question about this product ManufacturerHollandspiele Description Operation Unthinkable, designed by Ty Bomba, allows one or two players to explore the possible outcomes inherent in the campaign that would’ve resulted had Winston Churchill’s plan for starting World War III in July 1945 been put into effect. The general flow of the game inescapably has the Allies on the offensive at its start. On the Soviet side, that player is immediately faced with a decision to either “fight forward,” with Berlin as the central core of that gambit, or retreating east with the idea of slowly wearing down the Allied 1 / 2 Solitaire : Operation Unthinkable: Churchill's World War III offensive and then counterattacking into its flanks late in the game. Further, though the Allies have the ability to make paradrops and amphibious invasions, they lack the dedicated manpower necessary to make such gambits automatically decisive. Most games are decided either in and around Berlin or somewhere east of the Oder-Neisse line. A flexible turn structure that permits each player to choose the nature of his turn (move-combat, combat-move, or combat-combat), and a number of options (the aforementioned paradrops and amphibious invasions, plus bomber support, atom bombs, Soviet air surge, and reinforcements) allow you to tailor the game to your own strategy and play-style.