Download Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Isaiah Berlin Papers (PDF)

Catalogue of the papers of Sir Isaiah Berlin, 1897-1998, with some family papers, 1903-1972 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on 2019-10-14 Finding aid written in English Bodleian Libraries Weston Library Broad Street Oxford, , OX1 3BG [email protected] https://www.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/weston Catalogue of the papers of Sir Isaiah Berlin, 1897-1998, with some family papers, 1903-1972 Table Of Contents Summary Information .............................................................................................................................. 4 Language of Materials ......................................................................................................................... 4 Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Biographical / Historical ..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents ............................................................................................................................. 5 Arrangement ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Custodial History ................................................................................................................................. 5 Immediate Source of Acquisition ....................................................................................................... -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

In a Rather Emotional State?' the Labour Party and British Intervention in Greece, 1944-5

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE 'In a rather emotional state?' The Labour party and British intervention in Greece, 1944-5 AUTHORS Thorpe, Andrew JOURNAL The English Historical Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 12 February 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/18097 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication 1 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45* Professor Andrew Thorpe Department of History University of Exeter Exeter EX4 4RJ Tel: 01392-264396 Fax: 01392-263305 Email: [email protected] 2 ‘IN A RATHER EMOTIONAL STATE’? THE LABOUR PARTY AND BRITISH INTERVENTION IN GREECE, 1944-45 As the Second World War drew towards a close, the leader of the Labour party, Clement Attlee, was well aware of the meagre and mediocre nature of his party’s representation in the House of Lords. With the Labour leader in the Lords, Lord Addison, he hatched a plan whereby a number of worthy Labour veterans from the Commons would be elevated to the upper house in the 1945 New Years Honours List. The plan, however, was derailed at the last moment. On 19 December Attlee wrote to tell Addison that ‘it is wiser to wait a bit. We don’t want by-elections at the present time with our people in a rather emotional state on Greece – the Com[munist]s so active’. -

Michael Young: an Innovative Social Entrepreneur Stephen Meredith

Michael Young: an innovative social entrepreneur Stephen Meredith Michael Young resembled Cadmus. Whatever field he tilled, he sowed dragon’s teeth and armed men seemed to spring from the soil to form an organization and correct the abuses or stimulate the virtues he had discovered … Michael Young was a remarkable example of the merits of the education at Dartington Hall. He knew neither what a groove was nor the meaning of orthodoxy.1 Michael Young described Labour’s post-war programme in its reconstructive 1945 election manifesto as ‘Beveridge plus Keynes plus socialism’.2 Although Young is perhaps most famous for his principal contribution to Labour’s seminal 1945 election document, his was subsequently an uneasy relationship with the Labour Party and state socialism as a vehicle for the decentred, participatory, community and consumer-based social democracy he favoured.3 He always claimed to be ‘motivated by opposition’ and ‘moved by … the wonderful potential in all of us that isn’t being realised’ or recognised by large and remote state enterprise. This was supplemented by a communitarian and collaborative ethos of mutual aid, believing that smaller-scale ‘co-operatives were on principle the best sort of organisation for economic and social purposes’ (although conscious that even a large retail Co-operative movement could display tell-tale signs of bureaucratic centralism and consumer restriction).4 His problematic relationship with the Labour Party was evident soon after the emphatic post-war election victory he helped to create. -

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700 Folger Shakespeare Library Spring Semester Seminar 2016 Alexandra Walsham (University of Cambridge): [email protected] The origins, impact and repercussions of the English Reformation have been the subject of lively debate. Although it is now widely recognised as a protracted process that extended over many decades and generations, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the links between the life cycle and religious change. Did age and ancestry matter during the English Reformation? To what extent did bonds of blood and kinship catalyse and complicate its path? And how did remembrance of these events evolve with the passage of the time and the succession of the generations? This seminar will investigate the connections between the histories of the family, the perception of the past, and England’s plural and fractious Reformations. It invites participants from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to explore how the religious revolutions and movements of the period shaped, and were shaped by, the horizontal relationships that early modern people formed with their sibilings, relatives and peers, as well as the vertical ones that tied them to their dead ancestors and future heirs. It will also consider the role of the Reformation in reconfiguring conceptions of memory, history and time itself. Schedule: The seminar will convene on Fridays 1-4.30pm, for 10 weeks from 5 February to 29 April 2016, excluding 18 March, 1 April and 15 April. In keeping with Folger tradition, there will be a tea break from 3.00 to 3.30pm. -

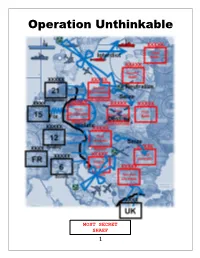

Operation Unthinkable

Operation Unthinkable MOST SECRET SHAEF 1 Mountaineer Game Design by Bob Hatcher I Setting The Game Map & Setup Page 3 Turn Sequence Overview Page 5 Victory Conditions Page 5 II Game Characteristics Geography and Economics Page 6 Allied Forces Page 7 Soviet Forces Page 7 Neutrals Page 8 Units Page 9 III Detailed Sequence of Events Page 11 IV Advanced Rules Page 14 V Parts list Page 16 VI Statistics Page 17 2 I FIGHTING OPERATION UNTHINKABLE At the end of May 1945, it is highly doubtful the Soviet Government is going to allow democratic processes in the countries they occupy. As Prime Minister Churchill feared, it appears the Russians are not going to honor the agreements made between Allies concerning the future of Central and Southern Europe. To impose the will of the United States, The British Empire, and their Allies, the Joint Planning Staff draws up plans for Operation Unthinkable, a plan completely dependent on strategic surprise and the support of other European powers, including those they liberate. Outnumbered 2 to 1 in men and materiel, the Allies will need every advantage in the opening offensive in a war that many thought was over for Europe. D Day is set for 1 July 1945… The Game Map & Setup The game map is divided into territories color-coded based on original national ownership. Allied territory is green and Soviet red. Large city areas are circular and may comprise more than one zone. Territories have a number in each area that indicates their value. There is a timeline chart for tracking turns and events, a chart for national morale, a chart for tracking the formation of NATO, and a chart for random events. -

Leonard Nelson — Bibliographie Der Sekundärliteratur

LEONARD NELSON — BIBLIOGRAPHIE DER SEKUNDÄRLITERATUR Jörg Schroth Aktualisierte Version der in Diskurstheorie und Sokratisches Gespräch, hrsg. von Dieter Krohn, Barbara Neißer und Nora Walter, Frankfurt am Main 1996, S. 183–248 veröffentlichten Bibliographie Stand: 20.02.05 Die Richtigkeit der bibliographischen Angaben der mit einem Asteriskus versehenen Titel ist nicht überprüft worden. Mit dieser Bibliographie wird kein Anspruch auf Vollständigkeit erhoben. Für Literaturhinweise danke ich Jos Kessels, Tadeusz Kononowicz, Rainer Loska, Gisela Raupach-Strey und Nora Walter. Besonderen Dank schulde ich Peter Schroth für die Be- schaffung von Literatur aus den USA. I. Aufsatzbände II. Biographie, Geschichte der politischen und pädagogischen Tätigkeit und Wirkung, Vorworte, Einleitungen, Lexikonartikel, Allgemeindarstellungen III. Theoretische Philosophie IV. Praktische Philosophie V. Sokratisches Gespräch VI. Rezensionen zu Nelson VII. Rezensionen zur Sekundärliteratur VIII. Erwähnungen 1 I. AUFSATZBÄNDE 1983 [1] Horster, Detlef/Krohn, Dieter (Hrsg.) (1983): Vernunft, Ethik, Politik. Gustav Heckmann zum 85. Geburtstag, Hannover (358 S.) 1994 [2] Kleinknecht, Reinhard/Neißer, Barbara (Hrsg.) (1994): Leonard Nelson in der Diskussion, Frankfurt a. M. (184 S.) (= „Sokratisches Philosophieren“ – Schriftenreihe der Philosophisch-Politischen Akademie, hrsg. von Silvia Knappe, Dieter Krohn, Nora Walter, Band 1). Rezensionen: [744], [767] 1996 [3] Knappe, Silvia/Krohn, Dieter/Walter, Nora (Hrsg.) (1996): Vernunftbegriff und Menschenbild bei Leonard Nelson, Frankfurt a. M. (151 S.) (= „Sokra- tisches Philosophieren“ – Schriftenreihe der Philosophisch-Politischen Akademie Band 2) 1974 [4] Knigge, Friedrich (Hrsg.) (1974): Beiträge zur Friedensforschung im Werk Leo- nard Nelsons. Vier von der Philosophisch-Politischen Akademie Kassel preisgekrönte Arbeiten, Hamburg (VI + 194 S.) (= Beiheift 1 zur Zeit- schrift Ratio) Rezension: [755] 1989 [5] Krohn, Dieter/Horster, Detlef/Heinen-Tenrich, Jürgen (Hrsg.) (1989): Das Sokra- tische Gespräch – Ein Symposion, Hamburg (171 S.). -

H-Diplo Roundtables, Vol. XIV, No. 8

2012 H-Diplo Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse Roundtable Web/Production Editor: George Fujii H-Diplo Roundtable Review www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Commissioned for H-Diplo by Thomas Maddux Volume XIV, No. 8 (2012) Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State 12 November 2012 University, Northridge Frank Costigliola. Roosevelt's Lost Alliances: How Personal Politics Helped Start the Cold War. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012. ISBN: 9780691121291 (cloth, $35.00); 9781400839520 (eBook, $35.00). Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XIV-8.pdf Contents Introduction by Thomas Maddux, California State University Northridge............................... 2 Review by Michaela Hoenicke Moore, University of Iowa ....................................................... 8 Review by Michael Holzman, Independent Scholar ............................................................... 15 Review by J Simon Rofe, SOAS, University of London ............................................................ 18 Review by David F. Schmitz, Whitman College ....................................................................... 21 Review by Michael Sherry, Northwestern University ............................................................. 25 Review by Katherine A. S. Sibley, Saint Joseph’s University ................................................... 29 Author’s Response by Frank Costigliola, University of Connecticut ....................................... 33 Copyright © 2012 H-Net: Humanities and -

Crown Copyright Catalogue Reference

(c) crown copyright Catalogue Reference:CAB/128/41 Image Reference:0041 THIS DOCUMENT IS THE PROPERTY OF HER BRITANNIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT Printed for the Cabinet. September 1966 CC (66) Copy No. 3 7 41st Conclusions CABINET CONCLUSIONS of a Meeting of the Cabinet held at JO Downing Street, S.W.1, on Tuesday, 2nd August, 1966, at 10 a.m. Present: The Right Hon. HAROLD WILSON, M P, Prime Minister The Right Hon. HERBERT BOWDEN, The Right Hon. LORD GARDINER, M p, Lord President of the Council Lord Chancellor The Right Hon. JAMES CALLAGHAN, The Right Hon. MICHAEL STEWART, MP, Chancellor of the Exchequer M P, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs The Right Hon. DENIS HEALEY, M P, The Right Hon. ARTHUR BOTTOMLEY, Secretary of State for Defence M P, Secretary of State for Common wealth Affairs The Right Hon. ROY JENKINS, MP, The Right Hon. WILLIAM ROSS, M P, Secretary of State for the Home Secretary of State for Scotland Department The Right Hon. DOUGLAS HOUGHTON, The Right Hon. DOUGLAS JAY, MP, M P, Minister without Portfolio President of the Board of Trade The Right Hon. ANTHONY GREENWOOD, The Right Hon. ANTHONY CROSLAND, M p, Minister of Overseas Develop M p, Secretary of State for Education ment and Science The Right Hon. RICHARD GROSSMAN, The Right Hon. THE EARL OF MP, Minister of Housing and Local LONGFORD, Lord Privy Seal Government (Items 1-5) The Right Hon. R. J. GUNTER, MP, The Right Hon. FRED PEART, MP, Minister of Labour Minister of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food The Right Hon. -

New Books Catalogue 2017-18 Tm

CLASSICAL STUDIES, HISTORY& ARCHAEOLOGY NEW BOOKS CATALOGUE 2017-18 TM Instant digital access to more than 6,000 eBooks across the social sciences and humanities, including titles from The Arden Shakespeare, Continuum, Bristol Classical Press, and Berg. Subjects covered include: Anthropology • Biblical Studies • Classical Studies & Archaeology • Education • Film & Media • History • Law • Linguistics • Literary Studies • Philosophy • Religious Studies • Theology CONTENT HIGHLIGHTS FEATURES • 125 Collections, expanded annually by subject discipline • Advanced and full text search across all content. • Archive Collections in key subject areas such as ancient • Filter results by subject, series, or collection history, Christology, continental philosophy, and more • Pagination matches print exactly • Special Collections such as International Critical • Personalization features: save searches, export citations Commentary, Ancient Commentators on Aristotle, and and favorite, download, or print documents Education Around the World series • Footnotes, endnotes, and bibliographic references are hyperlinked To register your interest for a free institutional trial, or for further information email: Americas: [email protected] UK, Europe, Middle East, Africa, Asia: [email protected] Australia and New Zealand: [email protected] www.bloomsburycollections.com Collections_advert.indd 1 28/07/2017 15:41 Contents Classical Studies History Ancient History ......................................................2 Historiography, -

Die Europavorstellungen Im Deutschen Und Im Französischen Widerstand Gegen Den Nationalsozialismus

Die Europavorstellungen im deutschen und im französischen Widerstand gegen den Nationalsozialismus 1933/40 bis 1945 Von der Fakultät VIII für Geschichts-, Sozial- und Wirtschaftswissenschaften der Universität Stuttgart zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie (Dr. Phil.) genehmigte Abhandlung Vorgelegt von Frédéric Stephan M.A. aus St. Maur des Fossés (Frankreich) Hauptberichter: Professor Dr. Axel Kuhn Mitberichter: Professor Dr. Gerhard Hirschfeld Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 19. November 2002 Historisches Institut der Universität Stuttgart 2002 Pour Fabrice Danken möchte ich an dieser Stelle allen, die mich bei der Fertigstellung meiner Arbeit unterstützt haben. Mein besonderer Dank gilt Prof. Dr. Axel Kuhn und Prof. Dr. Gerhard Hirschfeld sowie meiner Familie, insbesondere meiner Frau und meinem Vater. Inhalt Seite Einleitung 1 I. Zur Historiographie des Widerstandes gegen den Nationalsozialismus und zum Widerstandsbegriff in Frankreich und Deutschland I.1. Allgemeines 4 I.2. Historiographie der Widerstandsforschung in Deutschland 4 I.3. Historiographie der Widerstandsforschung in Frankreich 9 I.4. Fazit 11 II. Formen des Widerstandes 15 II.1. Nonkonformes Verhalten 16 II.2. Emigration, Widerstand im Exil 18 II.3. Humanitäre Hilfe 19 II.4. Offener Protest 20 II.5. Widerstand durch das Wort 21 II.6. Streiks, Sabotage 21 II.7. Verweigerung 22 II.8. Nachrichtenübermittlung 24 II.9. Attentate und bewaffneter Kampf 24 III. Widerstand in Deutschland - ein Abriss III.1. Allgemeines 28 III.2. Widerstand der traditionellen Eliten III.2.1. Der militärische Widerstand 29 III.2.2. Der Kreis um Carl Goerdeler 34 III.2.3. Der Kreisauer Kreis 37 III.2.4. Die Weiße Rose 40 III.3. Widerstand aus der Arbeiterbewegung III.3.1. -

History 2010 Final:Layout 1 15/6/10 11:06 Page 1 New Paperbacks Available September 2010 September Available 608Pp

History 2010 front cover 1-2:1 15/6/10 10:55 Page 1 2010 History fromyale History 2010 front cover 1-2:1 15/6/10 10:55 Page 2 Contents Subject Page PMC The Paul Mellon Centre New Paperbacks 1–3 MMA The Metropolitan Museum of Art British History 4–11 YCBA Yale Centre for British Art International & General History 12–17 EH In association with English Heritage Russian History 18–20 Titles Receiving full trade discount European History 21–26 Medieval History 27 Yale Nota Bene Paperbacks Religious History 28–29 Ancient History & Archaeology 30–31 Science & Medicine 32–33 FRONT COVER: Orestes Pursued (Palmerston pursued by the Furies: Bright, Roebuck and Military History 34 Disraeli), Punch, 19 June 1858 (detail). Hulton Archive/Getty Images. From: Palmerston: A Biography by David Brown, see page 4. American History 35–39 Index 40–42 yale university press 47 Bedford Square • London WC1B 3DP www.yalebooks.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] History 2010 Final:Layout 1 15/6/10 11:06 Page 1 New Paperbacks Available September 2010 Available 608pp. 20 b/w + 15 colour illus. 978-0-300-16892-1 £10.99* Paper ISBN 2010 384pp. 32 b/w illus. 978-0-300-16394-0 £12.99* Paper ISBN Available October 2010 Available 288pp. 16 b/w illus. 978-0-300-16886-0 £9.99* Paper ISBN Available September 2010 Available 368pp. 80 b/w + 25 colour illus. 978-0-300-16896-9 £10.99* Paper ISBN September 2010 Available 280pp. 30 colour illus. 978-0-300-16889-1 £12.99* Paper ISBN Behind Closed Doors Fires of Faith Demobbed The Master Croatia At Home in Georgian England Catholic England