10Th Annual Activity Report B) the Session Report C) the Final Communiqutheta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ahg/229 (Xxxvii)

FIFTEENTH ANNUAL ACTIVITY REPORT OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS 2001 - 2002 1 FIFTEENTH ANNUAL ACTIVITY REPORT OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS 2001 - 2002 I. ORGANISATION OF WORK A. Period covered by the Report 1. The 14th Annual Activity Report was adopted by the 37th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) meeting in July 2001 in Lusaka, Zambia by decision AHG/229 (XXXVII). During the above Summit meeting of Heads of State, a new Secretary-General of the OAU – Mr Amara Essy was elected. Three new persons were elected members of the African Commission namely – Dr. Angela Melo, Mrs Salimata Sawadogo and Mr Yasser Sid Ahmed El Hassan. One member was re-elected to the Commission – Mr Kamel Rezag Bara. The Fifteenth Annual Activity Report covers the 30th and 31st Ordinary Sessions of the Commission respectively held from 13th to 27th October 2001 in Banjul, The Gambia and from 2nd to 16th May 2002 in Pretoria, South Africa. B. Status of ratification 2. All OAU Member States are parties to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. C. Sessions and Agenda 3. Since the adoption of the fourteenth Annual Activity Report in July 2001, the Commission has held two Ordinary Sessions as indicated in the paragraphs above. The agenda for each of the sessions is contained in Annex I to this report. D. Composition and participation 4. At its 30th Ordinary Session, Commissioner Kamel Rezag-Bara and Commissioner Jainaba Johm were elected into office as Chairperson and Vice-Chairperson of the African Commission respectively. -

Jort N° 079/2010

TRADUCTION FRANÇAISE POUR INFORMATION er ème Vendredi 22 chaouel 1431 – 1 octobre 2010 153 année N° 79 Sommaire Décrets et Arrêtés Premier Ministère Décret n° 2010-2437 du 28 septembre 2010, complétant le décret n° 2007- 1260 du 21 mai 2007, fixant les cas où le silence de l'administration vaut acceptation implicite.......................................................................................... 2693 Nomination d'un membre au conseil d'établissement du centre d'information, de formation, d'études et de documentation sur les associations.................... 2694 Ministère de l'Intérieur et du Développement Local Arrêté du ministre de l'intérieur et du développement local du 27 septembre 2010, portant ouverture d'un concours interne sur dossiers pour la promotion au grade d'administrateur en chef du service social appartenant au corps des personnels du service social des administrations publiques..................... 2694 Arrêté du ministre de l'intérieur et du développement local du 27 septembre 2010, portant ouverture d'un concours interne sur épreuves pour la promotion au grade d'administrateur conseiller du service social appartenant au corps des personnels du service social des administrations publiques...... 2695 Arrêté du ministre de l'intérieur et du développement local du 27 septembre 2010, portant ouverture d'un concours interne sur épreuves pour la promotion au grade de conservateur de bibliothèques ou de documentation appartenant au corps des personnels des bibliothèques et de la documentation dans les administrations publiques.......................................... 2695 Arrêté du ministre de l'intérieur et du développement local du 27 septembre 2010, portant ouverture d'un concours interne sur épreuves pour la promotion au grade de technicien supérieur major de la santé publique du corps des techniciens de la santé publique..................................................... -

Annual Report 2003 Annual Report 2003

ISSN 1680-3809 6 QK-AA-04-001-EN-C T H E TH E EU RO PEA N E U M BU D SM A N O ANNUAL REPORT 2003 R O P E A N O M B U D S M A N ANNUAL REPORT 2003 Publications O厭 ce P u blication s.eu .in t EN EN www.euro-ombudsman.eu.int am407904CoverEN_BAT.indd 1 2/09/04 10:50:42 Executive summary 9 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction 17 COMPLAINTS TO THE OMBUDSMAN 2 Complaints to the Ombudsman 23 AN INQUIRY 3 Decisions following an inquiry 35 DECISIONS FOLLOWING 4 Relations with other institutions RELATIONS WITH of the European Union 209 OTHER INSTITUTIONS 5 Relations with ombudsmen and AND SIMILAR BODIES similar bodies 217 RELATIONS WITH OMBUDSMEN 6 Public relations 227 ANNEXES PUBLIC RELATIONS Annexes 261 © The European Ombudsman 2004 All rights reserved. Reproduction for educational and non-commercial purposes is permi ed provided that the source is acknowledged. Photographs, unless otherwise indicated, are copyright of the European Ombudsman. The full text of the report is published on the internet at: h p://www.euro-ombudsman.eu.int/report/en/default.htm T HE EUROPEAN OMBUDSMAN P. N IKIFOROS DIAMANDOUROS Mr Pat Cox Strasbourg, 19 April 2004 President European Parliament Rue Wiertz B-1047 Brussels Mr President, In accordance with Article 195 (1) of the Treaty establishing the European Community and Article 3 (8) of the Decision of the European Parliament on the Regulations and General Conditions Governing the Performance of the Ombudsman’s Duties, I hereby present my report for the year 2003. -

WIPO/GRTKF/IC/2/16: Informe (Annex 1)

ANEXO I LISTA DE PARTICIPANTES I. ÉTATS/STATES (dans l’ordre alphabétique des noms français des États) (in the alphabetical order of the names in French of the States) AFRIQUE DU SUD/SOUTH AFRICA Sipho George NENE, Ambassador, Permanent Representative, Permanent Mission, Geneva MacDonald NETSHITENZHE, Director, IPR Policy, Department of Trade and Industry, Pretoria Fiola HOOSEN (Ms.), Second Secretary, Permanent Mission, Geneva ALGÉRIE/ALGERIA Nor-Eddine BENFREHA, conseiller, Mission permanente, Genève ALLEMAGNE/GERMANY Jürgen SCHMIDT-DWERTMANN, Deputy Director General, Federal Ministry of Justice, Berlin Hans Georg BARTELS, Counsellor, Federal Ministry of Justice, Berlin Almuth OSTERMEYER-SCHLÖDER (Mrs.), Counsellor, Federal Ministry for the Environment, the Protection of Nature and Nuclear Security, Bonn Rainer DOBBELSTEIN, First Counsellor, Permanent Mission, Geneva Mara Mechtild WESSELER (Mrs.), Counsellor, Permanent Mission, Geneva ANGOLA João Da Silva CONSTANTINO, Director General, National Institute for Cultural Industries (INIC), National Directorate of Entertainment and Copyright, Ministry of Culture, Luanda Damião João Antonio Pinto BAPTISTA, Jurist, National Institute for Cultural Industries (INIC), National Directorate of Entertainment and Copyright, Ministry of Culture, Luanda ARABIE SAOUDITE/SAUDI ARABIA Ibrahim AL-MUTAIRI, Patent Researcher, King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, Patent Office, Riyadh OMPI/GRTKF/IC/2/16 Anexo I, página 2 ARGENTINE/ARGENTINA Marta GABRIELONI (Sra.), Consejero, Misión Permanente, -

Forum Report Acknowledgements

Forum Report Acknowledgements The Global Child Nutrition Forum Report was made possible thanks to collaboration by the Forum organizing partners (The Global Child Nutrition Foundation, UN World Food Programme Centre of Excellence against Hunger, and the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Tunisia with critical support from the WFP Tunisia Country Office. All rights reserved. The 20th Annual Global Child Nutrition Forum organizing partners (The Global Child Nutrition Foundation, UN World Food Programme Centre of Excellence against Hunger, and the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Tunisia) encourage the use and dissemination of content in this product. Reproduction and dissemination thereof for educational or other non-commercial uses are authorized provided that appropriate acknowledgement of the organizing partners as the source is given and that the organizing partners’ endorsements of users’ views, products, or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation or commercial use rights should be addressed to GCNF at [email protected] EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The 20th annual Global Child Nutrition Forum was an opportunity to reflect on how much the global community has achieved over the past two decades and to plan how to capitalize on those gains in the future. Hosted for the first time in the Middle East and North Africa Region, the Forum drew on experiences of the region to address two topics: how food and nutrition secu- rity contribute to social stability and how well-designed and managed school meal programs support multiple social benefits. The Forum was a joint collaboration of the Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF), the WFP Centre of Excellence against Hunger, and the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Tunisia, with critical support from the WFP Tunisia Country Office. -

STI Tunis Aktualizace K 1.9.2009

SOUHRNNÁ TERITORIÁLNÍ INFORMACE Tunisko Souhrnná teritoriální informace Tunisko Zpracováno a aktualizováno zastupitelským ú řadem ČR v Tunisu ke dni 01.09.2009 Seznam kapitol souhrnné teritoriálné informace: 1. Základní informace o teritoriu 2. Vnitropolitická charakteristika 3. Zahrani čně-politická orientace 4. Ekonomická charakteristika zem ě 5. Finan ční a da ňový sektor 6. Zahrani ční obchod zem ě 7. Obchodní a ekonomická spolupráce s ČR 8. Základní podmínky pro uplatn ění českého zboží na trhu 9. Investi ční klima 10. Očekávaný vývoj v teritoriu © Zastupitelský ú řad Tunis (Tunisko) 1. Základní informace o teritoriu 1.1. Oficiální název státu • Tuniská republika • Al Džumhúrija At Tunisia • La République Tunisienne 1.2. Rozloha • 162 155 km 2 (z toho 25 000 km 2 pouš ť) 1.3. Po čet obyvatel, hustota na km², podíl ekonomicky činného obyvatelstva • Po čet obyvatelstva 10.326 600 tis. (r. 2008) • Hustota na 1 km 2 63,8 obyv. (r. 2005) • Podíl ekonomicky činného obyvatelstva 46,4 % 1.4. Pr ůměrný ro ční p řír ůstek obyvatelstva a jeho demografické složení • Pr ůměrný ro ční p řír ůstek obyvatelstva, 0,99 % (r. 2006) • Demografické složení obyvatelstva 0–4 roky 8,0 %0–14 let 24,6 % • 15–64 let 68,6 % • 65 let a více 6,7 % 1.5. Národnostní složení • Arabové 97 %, Berbe ři 1 %, Evropané 1 %, Židé 1 % 1.6. Náboženské složení • 98 % muslimové (islám sunnitského ritu), k řes ťané 1 %, židé a ostatní 1 % 1.7. Úřední jazyk a ostatní nej čast ěji používané jazyky • arabština • ostatní nej čast ěji používané jazyky: francouzština, mén ě angli čtina, italština a n ěmčina 1.8. -

Chapter Seven Seventh Annual Activity Report of the African Commission 1993-1994

Seventh Annual Activity Report Chapter Seven Seventh Annual Activity Report of the African commission 1993-1994 7th Annual Report 181 7th Annual Report Seventh Annual Activity Report I. ORGANISATION OF WORK A. Period covered by the report 1. The Sixth Annual Activity report of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights was adopted by the Twenty-ninth session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the OAU in its resolution AHG/Res. (XXIX) Rev. 1. The present report covers the 14th and 15th Ordinary Sessions held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from 1-10 December 1993 and in Banjul, The Gambia, from 18-27 April 1994 respectively. B. Status of ratification 2. By the 15th session of the Commission, all the Member States of the OAU, with the exception of Ethiopia, Swaziland, and Eritrea, had ratified or acceded to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. The list of States and dates of signature, ratification/accession and deposit of instruments is attached to this Volume as Appendix III. C. Session and Agenda 3. The Commission has held two ordinary sessions since the adoption of its Sixth Annual Activity Report. • The 14th Ordinary Session was held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, from 1-10 December 1993; • The 15th Ordinary Session was held in Banjul, The Gambia, from 18 - 27 April, 1994. The agenda for each of the two sessions is contained respectively in Annexes I and II of this report. The Items on extra-judicial executions, human rights education and the Fourth World Conference on Human Rights (Beijing 1995) were respectively proposed by the following NGOs: Amnesty International, The Decade for Human Rights Education and the Centre for the Development of Legal Resources and Research, in accordance with articles 6, 5 (a) of the Rules of Procedure of the Commission. -

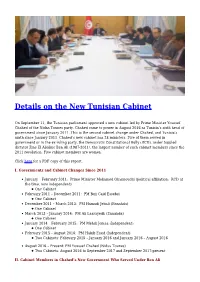

Details on the New Tunisian Cabinet

Details on the New Tunisian Cabinet On September 11, the Tunisian parliament approved a new cabinet led by Prime Minister Youssef Chahed of the Nidaa Tounes party. Chahed came to power in August 2016 as Tunisia’s sixth head of government since January 2011. This is the second cabinet change under Chahed, and Tunisia’s ninth since January 2011. Chahed’s new cabinet has 28 ministers. Five of them served in government or in the ex-ruling party, the Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD), under toppled dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali (1987-2011), the largest number of such cabinet members since the 2011 revolution. Five cabinet members are women. Click here for a PDF copy of this report. I. Governments and Cabinet Changes Since 2011 January – February 2011: Prime Minister Mohamed Ghannouchi (political affiliation: RCD at the time, now independent) One Cabinet February 2011 – December 2011: PM Beji Caid Essebsi One Cabinet December 2011 – March 2013: PM Hamadi Jebali (Ennahda) One Cabinet March 2013 – January 2014: PM Ali Laarayedh (Ennahda) One Cabinet January 2014 – February 2015: PM Mehdi Jomaa (Independent) One Cabinet February 2015 – August 2016: PM Habib Essid (Independent) Two Cabinets: February 2015 – January 2016 and January 2016 – August 2016 August 2016 – Present: PM Youssef Chahed (Nidaa Tounes) Two Cabinets: August 2016 to September 2017 and September 2017-present II. Cabinet Members in Chahed’s New Government Who Served Under Ben Ali Radhouane Ayara – Minister of Transportation Political affiliation: Nidaa Tounes New position, -

AHG/DEC 123(XXXIII) Taken During Its Meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe, from 2 - 4 June 1997

ELEVENTH ANNUAL ACTIVITY REPORT OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES` RIGHTS 1997 – 1998 1 DOC/OS/43(XXIII) ELEVENTH ANNUAL ACTIVITY REPORT OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES' RIGHTS 1997/98 I. ORGANIZATION OF WORK A. Period Covered by the Report 1. The Tenth Annual Activity report of the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights was adopted by the 33rd Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the Organization of African Unity in its decision AHG/DEC 123(XXXIII) taken during its meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe, from 2 - 4 June 1997. The Eleventh Annual Activity Report covers the 22nd and 23rd Ordinary Sessions held in Banjul, Gambia, from 2-11 November 1997 and from 20-29 April 1998 respectively. The addendum to this document concerns the part of the report covering the 23rd session. B. Status of Ratification 2. All the Member States of the OAU, with the exception of Eritrea and Ethiopia have ratified or acceded to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. Annex I contains the list of States parties to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights indicating inter alia 2 the dates of signature, ratification or accession, as well as the date of deposit of the instruments of ratification or accession as the case may be. C. Sessions and Agenda 3. The Commission held two ordinary sessions since the adoption of the Tenth Annual Activity Report in June 1997: - The 22nd Ordinary Session held in Banjul, The Gambia, the Headquarters of the Commission, from 2-11 November 1997; - The 23rd Ordinary Session held in Banjul, from 20-29 April 1998. -

Chapter Six Sixth Annual Activity Report of the African Commission

Sixth Annual Activity Report Chapter Six Sixth Annual Activity Report of the African Commission 1992 - 1993 6th Annual Report 142 6th Annual Report Sixth Annual Activity Report I. ORGANISATION OF WORK A. Period covered by the report 1. The Fifth Annual Activity Report was adopted by the Twenty-eighth ordinary session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government of the OAU by its resolution AHG/Res. 207 (XXVIII). The present report covers the Twelfth and Thirteenth ordinary sessions which were held in Banjul from 12 - 21 October 1992, and from 29 March to 7 April 1993 respectively. B. Status of ratification th 2. As at the date of the 13 session, 48 Member States had ratified the Charter. The list of those which have ratified the Charter is attached to this Volume as Appendix III. C. Sessions and agenda 3. The Commission has held two ordinary sessions since its fifth annual activity report was adopted. • the Twelfth ordinary session was held in Banjul, The Gambia, 12 to 21 October 1992; • the Thirteenth ordinary session was held in Banjul, The Gambia, from 29 March to 7 April 1993. The agenda of both sessions are attached hereto as Annexes I and II respectively. D. Composition and participation 4. The composition of the Commission has changed since the adoption of the last report. Mr. Mohammed Hatem Ben Salem was elected by the 28th Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government, on 1 July 1992, following the vacancy created by the death of Commissioner CLC Mubanga- Chipoya. The list of the other Commissioners is attached to this report as Annex III. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit „Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion“ Verfasserin Daniela Christiana Bichiou angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im Oktober 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 300 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Politikwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Otmar Höll Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion Seite 2 Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion Je vous remercie. Seite 3 Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion Seite 4 Bilaterale Beziehungen der Europäischen Union und Tunesiens unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Mittelmeerunion Inhalt ABKÜRZUNGSVERZEICHNIS .............................................................................................................................. 7 VORWORT ........................................................................................................................................................ 8 1. EINLEITUNG ............................................................................................................................................ 10 2. THEORETISCHE GRUNDLAGE .................................................................................................................. -

Ccw/Conf/Ii/2

CCW/CONF.II/2 SECOND REVIEW CONFERENCE OF THE STATES PARTIES TO THE CONVENTION ON PROHIBITIONS OR RESTRICTIONS ON THE USE OF CERTAIN CONVENTIONAL WEAPONS WHICH MAY BE DEEMED TO BE EXCESSIVELY INJURIOUS OR TO HAVE INDISCRIMINATE EFFECTS Geneva, 11-21 December 2001 FINAL DOCUMENT Geneva, 2001 .,. llflliiJUHIImf[lfiiiHUI:IUIIJIIIII u~. * 2 0 0 2 0 6 0 2 6 1 * ENG CCW/CONF .II/2 page iii CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Part I: Report of the Second Review Conference I. Introduction...................................................... 1 - 8 2 II. Organization of the Second Review Conference ..........9- 24 3 III. Work of the Second Review Conference .................25 - 31 5 IV. Decisions and Recommendations ......................... 32 - 34 6 Part II: Final Declaration .................................................................. 8 Part III: Documents of the Second Review Conference - Agenda of the Second Review Conference ................................... 20 -Programme of Work of the Second Review Conference ................... 27 -Agenda of Main Committee I. ................................................ 29 -Report ofMain Committee 1. .................................................. 30 -Agenda ofMain Committee II ................................................ 41 -Report ofMain Committee II ................................................. 42 -Report of the Credentials Committee ........................................ 43 - Estimated Costs of the 2002 meeting ofthe States Parties to the Convention on the Prohibitions or Restrictions