Community, Honor, and Secession in the Deep South : Mississippi's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mississippi-State of the Union

MISSISSIPPI-STATE OF THE UNION DURING THE PAST several years in which the struggle for human rights rights in our country has reached a crescendo level, the state of ~ississippi has periodically been a focal point of national interest. The murder of young Emmett Till, the lynching of Charles Mack Parker in the "moderate" Gulf section of Mississippi, the "freedom rides" to Jackson, the events at Oxford, Mississippi, and the triple lynching of the martyred Civil Rights workers, Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman, have, figuratively, imprinted Mississippi on the national conscience. In response to the national concern arising from such events, most writings about Mississippi have been in the nature of reporting, with emotional appeal and shock-value being the chief characteristics of such writing. FREEDOMWAYS is publishing this special issue on Mississippi to fill a need both for the Freedom Movement and the country. The need is for an in-depth analysis of Mississippi; of the political, economic and cultural factors which have historically served to institutionalize racism in this state. The purpose of such an analysis is perhaps best expressed in the theme that we have chosen: "Opening Up the Closed Society"; the purpose being to provide new insights rather than merely repeating well-known facts about Mississippi. The shock and embarrassment which events in Mississippi have sometimes caused the nation has also led to the popular notion that Mississippi is some kind of oddity, a freak in the American scheme-of-things. How many Civil Rights demonstrations have seen signs proclaiming-"bring Mississippi back into the Union." This is a well-intentioned but misleading slogan. -

The Free State of Winston"

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2019 Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston" Susan Neelly Deily-Swearingen University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Deily-Swearingen, Susan Neelly, "Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston"" (2019). Doctoral Dissertations. 2444. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2444 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REBEL REBELS: RACE, RESISTANCE, AND REMEMBRANCE IN THE FREE STATE OF WINSTON BY SUSAN NEELLY DEILY-SWEARINGEN B.A., Brandeis University M.A., Brown University M.A., University of New Hampshire DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History May 2019 This dissertation has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in History by: Dissertation Director, J. William Harris, Professor of History Jason Sokol, Professor of History Cynthia Van Zandt, Associate Professor of History and History Graduate Program Director Gregory McMahon, Professor of Classics Victoria E. Bynum, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History, Texas State University, San Marcos On April 18, 2019 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Cultural Resources Overview

United States Department of Agriculture Cultural Resources Overview F.orest Service National Forests in Mississippi Jackson, mMississippi CULTURAL RESOURCES OVERVIEW FOR THE NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI Compiled by Mark F. DeLeon Forest Archaeologist LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI USDA Forest Service 100 West Capitol Street, Suite 1141 Jackson, Mississippi 39269 September 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures and Tables ............................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 1 Cultural Resources Cultural Resource Values Cultural Resource Management Federal Leadership for the Preservation of Cultural Resources The Development of Historic Preservation in the United States Laws and Regulations Affecting Archaeological Resources GEOGRAPHIC SETTING ................................................ 11 Forest Description and Environment PREHISTORIC OUTLINE ............................................... 17 Paleo Indian Stage Archaic Stage Poverty Point Period Woodland Stage Mississippian Stage HISTORICAL OUTLINE ................................................ 28 FOREST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ............................. 35 Timber Practices Land Exchange Program Forest Engineering Program Special Uses Recreation KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE FOREST........... 41 Bienville National Forest Delta National Forest DeSoto National Forest ii KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE -

Antislavery Violence and Secession, October 1859

ANTISLAVERY VIOLENCE AND SECESSION, OCTOBER 1859 – APRIL 1861 by DAVID JONATHAN WHITE GEORGE C. RABLE, COMMITTEE CHAIR LAWRENCE F. KOHL KARI FREDERICKSON HAROLD SELESKY DIANNE BRAGG A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2017 Copyright David Jonathan White 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the collapse of southern Unionism between October 1859 and April 1861. This study argues that a series of events of violent antislavery and southern perceptions of northern support for them caused white southerners to rethink the value of the Union and their place in it. John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and northern expressions of personal support for Brown brought the Union into question in white southern eyes. White southerners were shocked when Republican governors in northern states acted to protect members of John Brown’s organization from prosecution in Virginia. Southern states invested large sums of money in their militia forces, and explored laws to control potentially dangerous populations such as northern travelling salesmen, whites “tampering” with slaves, and free African-Americans. Many Republicans endorsed a book by Hinton Rowan Helper which southerners believed encouraged antislavery violence and a Senate committee investigated whether an antislavery conspiracy had existed before Harpers Ferry. In the summer of 1860, a series of unexplained fires in Texas exacerbated white southern fear. As the presidential election approached in 1860, white southerners hoped for northern voters to repudiate the Republicans. When northern voters did not, white southerners generally rejected the Union. -

Arkansas Moves Toward Secession and War

RICE UNIVERSITY WITH HESITANT RESOLVE: ARKANSAS MOVES TOWARD SECESSION AND WAR BY JAMES WOODS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS Dr.. Frank E. Vandiver Houston, Texas ABSTRACT This work surveys the history of ante-bellum Arkansas until the passage of the Ordinance of Secession on May 6, 186i. The first three chapters deal with the social, economic, and politicai development of the state prior to 1860. Arkansas experienced difficult, yet substantial .social and economic growth during the ame-belium era; its percentage of population increase outstripped five other frontier states in similar stages of development. Its growth was nevertheless hampered by the unsettling presence of the Indian territory on its western border, which helped to prolong a lawless stage. An unreliable transportation system and a ruinous banking policy also stalled Arkansas's economic progress. On the political scene a family dynasty controlled state politics from 1830 to 186u, a'situation without parallel throughout the ante-bellum South. A major part of this work concentrates upon Arkansas's politics from 1859 to 1861. In a most important siate election in 1860, the dynasty met defeat through an open revolt from within its ranks led by a shrewd and ambitious Congressman, Thomas Hindman. Hindman turned the contest into a class conflict, portraying the dynasty's leadership as "aristocrats" and "Bourbons." Because of Hindman's support, Arkansans chose its first governor not hand¬ picked by the dynasty. By this election the people handed gubernatorial power to an ineffectual political novice during a time oi great sectional crisis. -

Spring/Summer 2016 No

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXVIII Spring/Summer 2016 No. 1 and No. 2 CONTENTS Introduction to Vintage Issue 1 By Dennis J. Mitchell Mississippi 1817: A Sociological and Economic 5 Analysis (1967) By W. B. Hamilton Protestantism in the Mississippi Territory (1967) 31 By Margaret DesChamps Moore The Narrative of John Hutchins (1958) 43 By John Q. Anderson Tockshish (1951) 69 By Dawson A. Phelps COVER IMAGE - Francis Shallus Map, “The State Of Mississippi and Alabama Territory,” courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. The original source is the Birmingham Public Library Cartography Collection. Recent Manuscript Accessions at Mississippi Colleges 79 University Libraries, 2014-15 Compiled by Jennifer Ford The Journal of Mississippi History (ISSN 0022-2771) is published quarterly by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 200 North St., Jackson, MS 39201, in cooperation with the Mississippi Historical Society as a benefit of Mississippi Historical Society membership. Annual memberships begin at $25. Back issues of the Journal sell for $7.50 and up through the Mississippi Museum Store; call 601-576-6921 to check availability. The Journal of Mississippi History is a juried journal. Each article is reviewed by a specialist scholar before publication. Periodicals paid at Jackson, Mississippi. Postmaster: Send address changes to the Mississippi Historical Society, P.O. Box 571, Jackson, MS 39205-0571. Email [email protected]. © 2018 Mississippi Historical Society, Jackson, Miss. The Department of Archives and History and the Mississippi Historical Society disclaim any responsibility for statements made by contributors. INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction By Dennis J. Mitchell Nearing my completion of A New History of Mississippi, I was asked to serve as editor of The Journal of Mississippi History (JMH). -

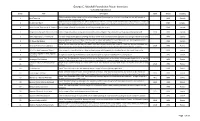

GCMF Poster Inventory

George C. Marshall Foundation Poster Inventory Compiled August 2011 ID No. Title Description Date Period Country A black and white image except for the yellow background. A standing man in a suit is reaching into his right pocket to 1 Back Them Up WWI Canada contribute to the Canadian war effort. A black and white image except for yellow background. There is a smiling soldier in the foreground pointing horizontally to 4 It's Men We Want WWI Canada the right. In the background there is a column of soldiers march in the direction indicated by the foreground soldier's arm. 6 Souscrivez à L'Emprunt de la "Victoire" A color image of a wide-eyed soldier in uniform pointing at the viewer. WWI Canada 2 Bring Him Home with the Victory Loan A color image of a soldier sitting with his gun in his arms and gear. The ocean and two ships are in the background. 1918 WWI Canada 3 Votre Argent plus 5 1/2 d'interet This color image shows gold coins falling into open hands from a Canadian bond against a blue background and red frame. WWI Canada A young blonde girl with a red bow in her hair with a concerned look on her face. Next to her are building blocks which 5 Oh Please Do! Daddy WWI Canada spell out "Buy me a Victory Bond" . There is a gray background against the color image. Poster Text: In memory of the Belgian soldiers who died for their country-The Union of France for Belgium and Allied and 7 Union de France Pour La Belqiue 1916 WWI France Friendly Countries- in the Church of St. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861 Michael Dudley Robinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Fulcrum of the Union: The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861 Michael Dudley Robinson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, Michael Dudley, "Fulcrum of the Union: The Border South and the Secession Crisis, 1859-1861" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 894. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/894 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. FULCRUM OF THE UNION: THE BORDER SOUTH AND THE SECESSION CRISIS, 1859- 1861 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by Michael Dudley Robinson B.S. North Carolina State University, 2001 M.A. University of North Carolina – Wilmington, 2007 May 2013 For Katherine ii Acknowledgements Throughout the long process of turning a few preliminary thoughts about the secession crisis and the Border South into a finished product, many people have provided assistance, encouragement, and inspiration. The staffs at several libraries and archives helped me to locate items and offered suggestions about collections that otherwise would have gone unnoticed. I would especially like to thank Lucas R. -

BARRY LYNDON a Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick Based on the Novel

BARRY LYNDON A Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick Based on the novel by William Makepeace Thackeray February 18, 1973 FADE IN: EXT. PARK - DAY Brief shot of duel. RODERICK (V.O.) My father, who was well-known to the best circles in this kingdom under the name of roaring Harry James, was killed in a duel, when I was fifteen years old. EXT. GARDEN - DAY Mrs. James, talking with a suitor; Roderick, at a distance. RODERICK (V.O.) My mother, after her husband's death, and her retirement, lived in such a way as to defy slander. She refused all offers of marriage, declaring that she lived now for her son only, and for the memory of her departed saint. EXT. STREET - DAY Mother and son walking together. RODERICK (V.O.) My mother was the most beautiful women of her day. But if she was proud of her beauty, to do her justice, she was still more proud of her son, and has said a thousand times to me that I was the handsomest fellow in the world. EXT. CHURCH - DAY Mother and son entering church. RODERICK (V.O.) The good soul's pleasure was to dress me; and on Sundays and Holidays, I turned out in a velvet coat with a silver-hilted sword by my side, and a gold garter at my knee as fine as any lord in the land. As we walked to church on Sundays, even the most envious souls would allow that there was not a prettier pair in the kingdom. EXT. FIELD - DAY A picnic. -

Identity, Dissent, and the Roots of Georgiaâ•Žs Middle Class, 1848

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2019 Identity, Dissent, and the Roots of Georgia’s Middle Class, 1848-1865 Thomas Robinson University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, Thomas, "Identity, Dissent, and the Roots of Georgia’s Middle Class, 1848-1865" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1674. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/1674 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDENTITY, DISSENT, AND THE ROOTS OF GEORGIA’S MIDDLE CLASS, 1848-1865 A Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Arch Dalrymple III Department of History The University of Mississippi by THOMAS W. ROBINSON December 2018 Copyright © 2018 by Thomas W. Robinson All rights reserved. ABSTRACT This dissertation, which focuses on Georgia from 1848 until 1865, argues that a middle class formed in the state during the antebellum period. By the time secession occurred, the class coalesced around an ideology based upon modernization, industrialization, reform, occupation, politics, and northern influence. These factors led the doctors, lawyers, merchants, ministers, shopkeepers, and artisans who made up Georgia’s middle class to view themselves as different than Georgians above or below them on the economic scale. The feeling was often mutual, as the rich viewed the middle class as a threat due to their income and education level while the poor were envious of the middle class. -

Fall/Summer 2017 Degree Candidate List

UNIVERSITY OF LOUISIANA MONROE Fall/Summer 2017 Degree Candidate List Students receiving Baccalaureate and Doctor of Pharmacy degrees were awarded Latin honors in accordance with the following guidelines: (*) Cum Laude: a cumulative grade point average (GPA) is within the range of 3.500 through 3.749. (†) Magna Cum Laude: a cumulative GPA is within the range of 3.750 through 3.899. (‡) Summa Cum Laude: a cumulative GPA is within the range of 3.900 through 4.000. (^)Honors — associate degree candidates with a cumulative GPA is within the range of 3.500 through 3.799 (~)High Honors — associate degree candidates with a cumulative GPA is within the range of 3.800 through 4.000 For any errors or omissions, please consult the Office of Marketing & Communication Academic List Page. Louisiana Allen Kinder: Ryan Alexander Walker, Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. Oakdale: Markus G. Santamaria, Bachelor of Science in Pharmaceutical Sciences. Ascension Donaldsonville: Edward Leroy Green, Bachelor of Science in Kinesiology. Gonzales: Monique Jolie Becnel, Master of Business Administration; Megan Leigh Shields, Master of Science in Psychology. Prairieville: Sarah Williams Goncalves, Master of Education in Education Technology Leadership; Emily Mor- gan Harvey, Bachelor of Science in Pharmaceutical Sciences†; Alec Christopher Osborne, Master of Science in Exercise Science; Kristen Lobue Wells, Master of Education in Education Technology Leadership. Avoyelles Hessmer: Kerra Faye Franks, Bachelor of Science in SpeechLlanguage Pathology*; Marksville: