The Journal of Mississippi History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid Into Alabama'

H-Indiana McMullen on Willett, 'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama' Review published on Monday, May 1, 2000 Robert L. Willett, Jr. The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama. Carmel: Guild Press of Indiana, 1999. 232 pp. $18.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-57860-025-0. Reviewed by Glenn L. McMullen (Curator of Manuscripts and Archives, Indiana Historical Society) Published on H-Indiana (May, 2000) A Union Cavalry Raid Steeped in Misfortune Robert L. Willett's The Lightning Mule Brigade is the first book-length treatment of Indiana Colonel Abel D. Streight's Independent Provisional Brigade and its three-week raid in spring 1863 through Northern Alabama to Rome, Georgia. The raid, the goal of which was to cut Confederate railroad lines between Atlanta and Chattanooga, was, in Willett's words, a "tragi-comic war episode" (8). The comic aspects stemmed from the fact that the raiding force was largely infantry, mounted not on horses but on fractious mules, anything but lightning-like, justified by military authorities as necessary to take it through the Alabama mountains. Willett's well-written and often moving narrative shifts between the forces of the two Union commanders (Streight and Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge) and two Confederate commanders (Col. Phillip Roddey and Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest) who were central to the story, staying in one camp for a while, then moving to another. The result is a highly textured and complex, but enjoyable, narrative. Abel Streight, who had no formal military training, was proprietor of the Railroad City Publishing Company and the New Lumber Yard in Indianapolis when the war began. -

Timeline 1864

CIVIL WAR TIMELINE 1864 January Radical Republicans are hostile to Lincoln’s policies, fearing that they do not provide sufficient protection for ex-slaves, that the 10% amnesty plan is not strict enough, and that Southern states should demonstrate more significant efforts to eradicate the slave system before being allowed back into the Union. Consequently, Congress refuses to recognize the governments of Southern states, or to seat their elected representatives. Instead, legislators begin to work on their own Reconstruction plan, which will emerge in July as the Wade-Davis Bill. [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/reconstruction/states/sf_timeline.html] [http://www.blackhistory.harpweek.com/4Reconstruction/ReconTimeline.htm] Congress now understands the Confederacy to be the face of a deeply rooted cultural system antagonistic to the principles of a “free labor” society. Many fear that returning home rule to such a system amounts to accepting secession state by state and opening the door for such malicious local legislation as the Black Codes that eventually emerge. [Hunt] Jan. 1 TN Skirmish at Dandridge. Jan. 2 TN Skirmish at LaGrange. Nashville is in the grip of a smallpox epidemic, which will carry off a large number of soldiers, contraband workers, and city residents. It will be late March before it runs its course. Jan 5 TN Skirmish at Lawrence’s Mill. Jan. 10 TN Forrest’s troops in west Tennessee are said to have collected 2,000 recruits, 400 loaded Wagons, 800 beef cattle, and 1,000 horses and mules. Most observers consider these numbers to be exaggerated. “ The Mississippi Squadron publishes a list of the steamboats destroyed on the Mississippi and its tributaries during the war: 104 ships were burned, 71 sunk. -

The Free State of Winston"

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2019 Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston" Susan Neelly Deily-Swearingen University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Deily-Swearingen, Susan Neelly, "Rebel Rebels: Race, Resistance, and Remembrance in "The Free State of Winston"" (2019). Doctoral Dissertations. 2444. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/2444 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REBEL REBELS: RACE, RESISTANCE, AND REMEMBRANCE IN THE FREE STATE OF WINSTON BY SUSAN NEELLY DEILY-SWEARINGEN B.A., Brandeis University M.A., Brown University M.A., University of New Hampshire DISSERTATION Submitted to the University of New Hampshire In Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History May 2019 This dissertation has been examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in History by: Dissertation Director, J. William Harris, Professor of History Jason Sokol, Professor of History Cynthia Van Zandt, Associate Professor of History and History Graduate Program Director Gregory McMahon, Professor of Classics Victoria E. Bynum, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of History, Texas State University, San Marcos On April 18, 2019 Original approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. -

Under the Arch

Summer, 1982 Hours of operation A free publication to May 29-September 6 provide information Visitor Center, 8:00 a.m. under about the Jefferson to 10:00 p.m. National Expansion Tram Ride, 8:30 a.m. to Memorial 9:30p.m. the Museum of Westward Expansion, 8:00 a.m. to 1arc h 10:00 p.m. Inside this GATEWAY ARCH: issue How long does it take to ride to the top? Where do I A Monument purchase tickets? These and other often asked questions are answered in "Riding to For Our Time the Top." The Museum of Westward Expansion recreates one of the country's most colorful eras. The next page provides a map of the museum and two articles that explain how to view it. See It Today May 29-September 6: Monument to the Dream, a 30-minute film, documents the construction of the Gateway Arch. Shows begin at 8:15 a.m., 9:15 a.m., 10:45 a.m., 12:15 p.m., 1:45 p.m., 2:30 p.m., 3:15 p.m., 4:45 •i p.m., 6:15 p.m., 7:45 p.m. and 8:45 p.m. in Tucker Theater adja i cent to the Gateway Arch lobby. Charles M. Russell: American Artist, a 20-minute film, interprets i the life and significance of a well- known artist of the West. Shows s begin at 10:00 a.m., 11:30 a.m., •2 1:00 p.m., 4:00 p.m., 5:30 p.m. CO and 7:00 p.m. -

2011-Summer Timelines

OMENA TIMELINES Remembering Omena’s Generals and … The American Civil War Sesquicentennial A PUBLICATION OF THE OMENA HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 2011 From the Editor Jim Miller s you can see, our Timelines publica- tion has changed quite a bit. We have A taken it from an institutional “newslet- ter” to a full-blown magazine. To make this all possible, we needed to publish it annually rather than bi-annually. By doing so, we will be able to provide more information with an historical focus rather than the “news” focus. Bulletins and OHS news will be sent in multiple ways; by e-mail, through our website, published in the Leelanau Enterprise or through special mailings. We hope you like our new look! is the offi cial publication Because 2011 is the sesquicentennial year for Timelines of the Omena Historical Society (OHS), the start of the Civil War, it was only fi tting authorized by its Board of Directors and that we provide appropriately related matter published annually. for this issue. We are focusing on Omena’s three Civil War generals and other points that should Mailing address: pique your interest. P.O. Box 75 I want to take this opportunity to thank Omena, Michigan 49674 Suzie Mulligan for her hard work as the long- www.omenahistoricalsociety.com standing layout person for Timelines. Her sage Timelines advice saved me on several occasions and her Editor: Jim Miller expertise in laying out Timelines has been Historical Advisor: Joey Bensley invaluable to us. Th anks Suzie, I truly appre- Editorial Staff : Joan Blount, Kathy Miller, ciate all your help. -

Civil War Chronological History for 1864 (150Th Anniversary) February

Civil War Chronological History for 1864 (150th Anniversary) February 17 Confederate submarine Hunley sinks Union warship Housatonic off Charleston. February 20 Union forces defeated at Olustee, Florida (the now famous 54th Massachusetts took part). March 15 The Red River campaign in Louisiana started by Federal forces continued into May. Several battles eventually won by the Confederacy. April 12 Confederates recapture Ft. Pillow, Tennessee. April 17 Grant stops prisoner exchange increasing Confederate manpower shortage. April 30 Confederates defeat Federals at Jenkins Ferry, Arkansas and force them to withdraw to Little Rock. May 5 Battle of the Wilderness, Virginia. May 8‐21 Battle of Spotsylvania Courthouse, Virginia (heaviest battle May 12‐13). May 13 Battle at Resaca, Georgia as Sherman heads toward Atlanta. May 15 Battle of New Market, Virginia. May 25 Four day battle at New Hope Church, Georgia. June 1‐3 Battle of Cold Harbor, Virginia. Grants forces severely repulsed. June 10 Federals lose at Brice’s Crossroads, Mississippi. June 19 Siege of Petersburg, Virginia by Grant’s forces. June 19 Confederate raider, Alabama, sunk by United States warship off Cherbourg, France. June 27 Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia. July 12 Confederates reach the outskirts of Washington, D.C. but are forced to withdraw. July 15 Battle of Tupelo, Mississippi. July 20 Battle of Peachtree Creek, Georgia. July 30 Battle of the Crater, Confederates halt breakthrough. August 1 Admiral Farragut wins battle of Mobile Bay for the Union. September 1 Confederates evacuate Atlanta. September 2 Sherman occupies Atlanta. September 4 Sherman orders civilians out of Atlanta. September 19 Battle at Winchester, Virginia. -

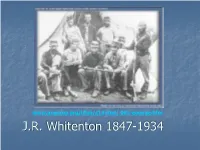

J.R Whitenton

www.aneuroa.org/html/c19html/ 001-emerge.htm J.R. Whitenton 1847-1934 The Beginning J.R. Whitenton was born in Madison co. Tennessee. Madison Co. is located north of Jackson, TN. Enlistment Mr. Whitenton enlisted in August of 1862 when he was 15. He was assigned to Company “C” 15th H Tennessee regiment, until December of 1864 when he was reassigned to the 13th H Tennessee regiment, Cavalry. The Regiment The 15th regiment, Tennessee Cavalry, Also called Stewarts Cavalry, was organized in August of 1863. It’s companies were from Dyer, Haywood, Gibson, and Fayette counties. It was stationed at Pikeville, MI. then was assigned to Colonel R.V. Richardson’s Brigade. Battles Mr. Whitenton was involved in several battles including: Tupelo, Mississippi, and Columbia, Tennessee. During battle he would carry wounded out off the field. Battle of Tupelo, Mississippi This battle was lead by Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee and Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest [CS], and Maj. Gen. A.J. Smith [US]. Smith was ordered not to attack without additional men, so he waited until Gen, Lee arrived with 2000 reinforcements. www.gettysburgfoundation.org/ history.html On the night of the 13th, Lee ordered an attack on the next morning. The next morning he launched several attacks all of which the Yanks beat. The fighting stopped after only a few hours. As a result the Union won and the confederates lost 1300 men. Battle of Columbia, Tennessee This battle was lead by Maj. Gen. John M. Schofield [US], and Gen. John Bell Hood [CS]. The Federals built two lines of earthworks south of the town while fighting with enemy cavalry on November 24 and 25. -

Arkansas Moves Toward Secession and War

RICE UNIVERSITY WITH HESITANT RESOLVE: ARKANSAS MOVES TOWARD SECESSION AND WAR BY JAMES WOODS A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS Dr.. Frank E. Vandiver Houston, Texas ABSTRACT This work surveys the history of ante-bellum Arkansas until the passage of the Ordinance of Secession on May 6, 186i. The first three chapters deal with the social, economic, and politicai development of the state prior to 1860. Arkansas experienced difficult, yet substantial .social and economic growth during the ame-belium era; its percentage of population increase outstripped five other frontier states in similar stages of development. Its growth was nevertheless hampered by the unsettling presence of the Indian territory on its western border, which helped to prolong a lawless stage. An unreliable transportation system and a ruinous banking policy also stalled Arkansas's economic progress. On the political scene a family dynasty controlled state politics from 1830 to 186u, a'situation without parallel throughout the ante-bellum South. A major part of this work concentrates upon Arkansas's politics from 1859 to 1861. In a most important siate election in 1860, the dynasty met defeat through an open revolt from within its ranks led by a shrewd and ambitious Congressman, Thomas Hindman. Hindman turned the contest into a class conflict, portraying the dynasty's leadership as "aristocrats" and "Bourbons." Because of Hindman's support, Arkansans chose its first governor not hand¬ picked by the dynasty. By this election the people handed gubernatorial power to an ineffectual political novice during a time oi great sectional crisis. -

Stalin's Apologist; Great Fire Of

The Robert F. Cairo Book Collection Lot # #Bks Book Titles &/or Topics of Books on Shelf Author(s) in order of lot listing Loc. 1 14 Mask of Treachery; The Hollow Men; Who Tell the People; Breaking from Costello; Sykes; Greider; Shainback; the KGB; Stalin's Apologist; Great Fire of London; No More Heroes; The Taylor; Hanson; Gabriel; Kennon; Dailey & DR Twilight of Democracy; Soviet Strategic Deception; The Kinder, Gentlier Parker; Gutman; Sterling Military; The Terror Network 2 10 Wartime Washington; Southern Bivouac, vol 1-6 (1992), Diary of Edmund Ruffin, Laas vol 1-3 (1990) DR 3 30 Official Records of the Union & Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, DR Series I: Vol. 1-27; Series II: Vol 1-3. (1987 reprint). (3 shelves) 4 127 Official Records of the Union & Confederate Armies in the War of the Rebellion, Series I: vol 1-53 (1985 reprint); Series II: vol 1-8; Series III: Vol 1-5; Series IV: vol DR 1-3 plus Index. Vol Series #112 & 113 are missing (7 shelves) 5 15 Military & political subjects DR 6 15 Prescott's (1869 Ed): Conquest of Peru, vol 1-2; Biographical & Critical Miscellaneous; Conquest of Mexico vol 1-3; Ferdinand & Isabella vol 1-3; Phillip DR the Second vol 1-3; Robetson's Charles the Fifth vol 1-3 7 20 The Grand Failure; Profile of Deception; Dringk; Stolen Valor; The Leopard's Spots; An Enormous Crime; Great Houses of San Francisco; History of Food; God DR Men & Wine 8 30 Various subjects: History, Woodworking, American flag, warfare, flim & DR folklore. -

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2014 By

MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE REGULAR SESSION 2014 By: Senator(s) Wilemon, Collins, Lee, To: Rules Jackson (11th) SENATE CONCURRENT RESOLUTION NO. 640 1 A CONCURRENT RESOLUTION TO COMMEMORATE THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY 2 OF THE BATTLE OF BRICE'S CROSSROADS AND TUPELO-HARRISBURG AND TO 3 RECOGNIZE THE GRAND REENACTMENT OF THIS IMPORTANT JUNE 10, 1864, 4 ENGAGEMENT. 5 WHEREAS, the State of Mississippi witnessed critically 6 important American Civil War military engagements on its soil, 7 including the Siege of Vicksburg, the Battle of Champion Hill, the 8 Battle of Iuka, the Battle of Corinth and the Battle of Brice's 9 Crossroads, and hosts historic sites related to these strategic 10 engagements which are nationally recognized centers of expertise 11 in the study of the American Civil War; and 12 WHEREAS, the records show that the State of Mississippi 13 contributed 49 regular Infantry Regiments, 25 regular Cavalry and 14 Artillery Regiments, 78,000 men in service of which 60,000 were 15 lost in action or by disease, the Commander-in-Chief of the 16 Confederate armies (President Jefferson F. Davis) and 33 Generals 17 of the Confederate Army whose remains lie in Mississippi soil; and 18 WHEREAS, visitors will be transported back in time during a 19 three-day event to commemorate the anniversaries of the Battle of S. C. R. No. 640 *SS01/R1222* ~ OFFICIAL ~ N1/2 14/SS01/R1222 PAGE 1 20 Brice's Crossroads and the Battle of Tupelo-Harrisburg on June 21 13-15, 2014. Cleburne's Division of Reenactors will host the 22 event on the 1500-acre Brice's Crossroads Battlefield located at 23 the intersection of Highway 370 and CR 833, and present two 24 full-scale scripted battles with historically authentic scenarios. -

Group Tour Manual

Group Tour GUIDE 1 5 17 33 36 what's inside 1 WELCOME 13 FUN FACTS – (ESCORT NOTES) 2 WEATHER INFORMATION 17 ATTRACTIONS 3 GROUP TOUR SERVICES 30 SIGHTSEEING 5 TRANSPORTATION INFORMATION 32 TECHNICAL TOURS Airport 35 PARADES Motorcoach Parking – Policies 36 ANNUAL EVENTS Car Rental Metro & Trolley 37 SAMPLE ITINERARIES 7 MAPS Central Corridor Metro Forest Park Downtown welcome St. Louis is a place where history and imagination collide, and the result is a Midwestern destination like no other. In addition to a revitalized downtown, a vibrant, new hospitality district continues to grow in downtown St. Louis. More than $5 billion worth of development has been invested in the region, and more exciting projects are currently underway. The Gateway to the West offers exceptional music, arts and cultural options, as well as such renowned – and free – attractions as the Saint Louis Art Museum, Zoo, Science Center, Missouri History Museum, Citygarden, Grant’s Farm, Laumeier Sculpture Park, and the Anheuser-Busch brewery tours. Plus, St. Louis is easy to get to and even easier to get around in. St. Louis is within approximately 500 miles of one-third of the U.S. population. Each and every new year brings exciting additions to the St. Louis scene – improved attractions, expanded attractions, and new attractions. Must See Attractions There’s so much to see and do in St. Louis, here are a few options to get you started: • Ride to the top of the Gateway Arch, towering 630-feet over the Mississippi River. • Visit an artistic oasis in the heart of downtown. -

Letter to Congressional Leaders Transmitting a Report on Funding for Trade and Development Agency Activities with Respect to China January 13, 2001

Administration of William J. Clinton, 2001 / Jan. 16 its agencies or instrumentalities, officers, em- NOTE: An original was not available for ployees, or any other person, or to require any verification of the content of this memorandum, procedures to determine whether a person is which was not received for publication in the Fed- a refugee. eral Register. You are authorized and directed to publish this memorandum in the Federal Register. WILLIAM J. CLINTON Letter to Congressional Leaders Transmitting a Report on Funding for Trade and Development Agency Activities With Respect to China January 13, 2001 Dear Mr. Speaker: (Dear Mr. President:) Development Agency with respect to the Peo- I hereby transmit a report including my rea- ple’s Republic of China. sons for determining, pursuant to the authority Sincerely, vested in me by section 902 of the Foreign WILLIAM J. CLINTON Relations Authorization Act, Fiscal Years 1990 and 1991 (Public Law 101–246), that it is in NOTE: Identical letters were sent to J. Dennis the national interest of the United States to Hastert, Speaker of the House of Representatives, terminate the suspension on the obligation of and Albert Gore, Jr., President of the Senate. This funds for any new activities of the Trade and letter was released by the Office of the Press Sec- retary on January 16. Remarks on Presenting the Medal of Honor January 16, 2001 The President. Good morning, and please be So when the Medal of Honor was instituted seated. I would like to first thank Chaplain Gen- during the Civil War, it was agreed it would eral Hicks for his invocation and welcome the be given only for gallantry, at the risk of one’s distinguished delegation from the Pentagon who life above and beyond the call of duty.