Union Treatment of Civilians and Private Property in Mississippi, 1862-1865: an Examination of Theory and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid Into Alabama'

H-Indiana McMullen on Willett, 'The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama' Review published on Monday, May 1, 2000 Robert L. Willett, Jr. The Lightning Mule Brigade: Abel Streight's 1863 Raid into Alabama. Carmel: Guild Press of Indiana, 1999. 232 pp. $18.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-57860-025-0. Reviewed by Glenn L. McMullen (Curator of Manuscripts and Archives, Indiana Historical Society) Published on H-Indiana (May, 2000) A Union Cavalry Raid Steeped in Misfortune Robert L. Willett's The Lightning Mule Brigade is the first book-length treatment of Indiana Colonel Abel D. Streight's Independent Provisional Brigade and its three-week raid in spring 1863 through Northern Alabama to Rome, Georgia. The raid, the goal of which was to cut Confederate railroad lines between Atlanta and Chattanooga, was, in Willett's words, a "tragi-comic war episode" (8). The comic aspects stemmed from the fact that the raiding force was largely infantry, mounted not on horses but on fractious mules, anything but lightning-like, justified by military authorities as necessary to take it through the Alabama mountains. Willett's well-written and often moving narrative shifts between the forces of the two Union commanders (Streight and Brig. Gen. Grenville Dodge) and two Confederate commanders (Col. Phillip Roddey and Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest) who were central to the story, staying in one camp for a while, then moving to another. The result is a highly textured and complex, but enjoyable, narrative. Abel Streight, who had no formal military training, was proprietor of the Railroad City Publishing Company and the New Lumber Yard in Indianapolis when the war began. -

Record of the Organizations Engaged in the Campaign, Siege, And

College ILttirarjj FROM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ' THROUGH £> VICKSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK COMMISSION. RECORD OF THE ORGANIZATIONS ENGAGED IN THE CAMPAIGN, SIEGE, AND DEFENSE OF VICKSBURG. COMPILED FROM THE OFFICIAL RECORDS BY jomsr s. KOUNTZ, SECRETARY AND HISTORIAN OF THE COMMISSION. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1901. PREFACE. The Vicksburg campaign opened March 29, 1863, with General Grant's order for the advance of General Osterhaus' division from Millikens Bend, and closed July 4^, 1863, with the surrender of Pem- berton's army and the city of Vicksburg. Its course was determined by General Grant's plan of campaign. This plan contemplated the march of his active army from Millikens Bend, La. , to a point on the river below Vicksburg, the running of the batteries at Vicksburg by a sufficient number of gunboats and transports, and the transfer of his army to the Mississippi side. These points were successfully accomplished and, May 1, the first battle of the campaign was fought near Port Gibson. Up to this time General Grant had contemplated the probability of uniting the army of General Banks with his. He then decided not to await the arrival of Banks, but to make the cam paign with his own army. May 12, at Raymond, Logan's division of Grant's army, with Crocker's division in reserve, was engaged with Gregg's brigade of Pemberton's army. Gregg was largely outnum bered and, after a stout fight, fell back to Jackson. The same day the left of Grant's army, under McClernand, skirmished at Fourteen- mile Creek with the cavalry and mounted infantry of Pemberton's army, supported by Bowen's division and two brigades of Loring's division. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

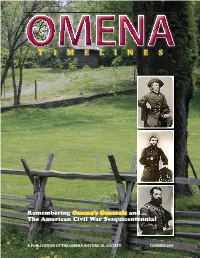

2011-Summer Timelines

OMENA TIMELINES Remembering Omena’s Generals and … The American Civil War Sesquicentennial A PUBLICATION OF THE OMENA HISTORICAL SOCIETY SUMMER 2011 From the Editor Jim Miller s you can see, our Timelines publica- tion has changed quite a bit. We have A taken it from an institutional “newslet- ter” to a full-blown magazine. To make this all possible, we needed to publish it annually rather than bi-annually. By doing so, we will be able to provide more information with an historical focus rather than the “news” focus. Bulletins and OHS news will be sent in multiple ways; by e-mail, through our website, published in the Leelanau Enterprise or through special mailings. We hope you like our new look! is the offi cial publication Because 2011 is the sesquicentennial year for Timelines of the Omena Historical Society (OHS), the start of the Civil War, it was only fi tting authorized by its Board of Directors and that we provide appropriately related matter published annually. for this issue. We are focusing on Omena’s three Civil War generals and other points that should Mailing address: pique your interest. P.O. Box 75 I want to take this opportunity to thank Omena, Michigan 49674 Suzie Mulligan for her hard work as the long- www.omenahistoricalsociety.com standing layout person for Timelines. Her sage Timelines advice saved me on several occasions and her Editor: Jim Miller expertise in laying out Timelines has been Historical Advisor: Joey Bensley invaluable to us. Th anks Suzie, I truly appre- Editorial Staff : Joan Blount, Kathy Miller, ciate all your help. -

Chancellor Kent: an American Genius

Chicago-Kent Law Review Volume 38 Issue 1 Article 1 April 1961 Chancellor Kent: An American Genius Walter V. Schaefer Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Walter V. Schaefer, Chancellor Kent: An American Genius, 38 Chi.-Kent L. Rev. 1 (1961). Available at: https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cklawreview/vol38/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chicago-Kent Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarly Commons @ IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. CHICAGO-KENT LAW REVIEW Copyright 1961, Chicago-Kent College of Law VOLUME 38 APRIL, 1961 NUMBER 1 CHANCELLOR KENT: AN AMERICAN GENIUS Walter V. Schaefer* T HIS IS THE FIRST OPPORTUNITY I have had, during this eventful day, to express my deep appreciation of the honor that you have done me.' I realize, of course, that there is a large element of symbolism in your selection of Dr. Kirkland and me to be the recipients of honorary degress, and that through him you are honoring the bar of our community, and through me the judges who man its courts. Nevertheless, both of us are proud and happy that your choice fell upon us. I am particularly proud to have been associated with Weymouth Kirkland on this occasion. His contributions to his profession are many. One of the most significant was the pioneer role that he played in the development of a new kind of court room advocacy. -

Ask the Horseman, the Dog Fancier And

[Reprinted from THE POPULAR SCIENCE MONTHLY, May, 1913.] HEREDITY AND THE HALL OF FAME BY FREDERICK ADAMS WOODS, M.D. LECTURER ON EUGENICS IN THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY HAT is there in heredity ? Ask the horseman, the dog fancier W and the horticulturalist, and you will find that a belief in heredity is the cardinal point of all their work. Among animals and plants nothing is more obvious than the general resemblance of off spring to parents and the stock from which they come. With the high est-priced Jersey, the blue ribbon horse or a prize-winning dog, goes al ways the pedigree as the essential guarantee of worth. So in the general bodily features of human beings, no one questions the great force of inheritance or is surprised because those close of kin look very much alike. Similarities in eyes, nose, mouth, complexion, gestures or physique are accepted as a matter of course, and we never stop to wonder at what is in reality one of the greatest of all mysteries, the substantial repetition of the same sort of beings generation after generation. If heredity does so much in moulding the physical form, may it not do as much in determining the shape and quality of the brain, in short, the mental and moral man in his highest manifesta tion of genius-indeed the ego itself? Here we find differences of opinion, for man usually thinks of him self as in part at least a spiritual being, free to act according to his own will, unsubject to the laws of matter. -

American Civil War

American Civil War Major Battles & Minor Engagements 1861-1865 1861 ........ p. 2 1862 ........ p. 4 1863 ........ p. 9 1864 ........ p. 13 1865 ........ p. 19 CIVIL WAR IMPRESSIONIST ASSOCIATION 1 Civil War Battles: 1861 Eastern Theater April 12 - Battle of Fort Sumter (& Fort Moultie), Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The bombardment/siege and ultimate surrender of Fort Sumter by Brig. General P.G.T. Beauregard was the official start of the Civil War. https://www.nps.gov/fosu/index.htm June 3 - Battle of Philippi, (West) Virginia A skirmish involving over 3,000 soldiers, Philippi was the first battle of the American Civil War. June 10 - Big Bethel, Virginia The skirmish of Big Bethel was the first land battle of the civil war and was a portent of the carnage that was to come. July 11 - Rich Mountain, (West) Virginia July 21 - First Battle of Bull Run, Manassas, Virginia Also known as First Manassas, the first major engagement of the American Civil War was a shocking rout of Union soldiers by confederates at Manassas Junction, VA. August 28-29 - Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina September 10 - Carnifax Ferry, (West) Virginia September 12-15 - Cheat Mountain, (West) Virginia October 3 - Greenbrier River, (West) Virginia October 21 - Ball's Bluff, Virginia October 9 - Battle of Santa Rosa Island, Santa Rosa Island (Florida) The Battle of Santa Rosa Island was a failed attempt by Confederate forces to take the Union-held Fort Pickens. November 7-8 - Battle of Port Royal Sound, Port Royal Sound, South Carolina The battle of Port Royal was one of the earliest amphibious operations of the American Civil War. -

Where Mcgavock Fell

Where McGavock Fell A Trip to Raymond, Mississippi, To Visit the Ghost of Patrick Griffin and See the place Where His Stories of the Late Unpleasantness Between the States Took Place By Vic Socotra Copyright 2015 Captain Patrick Griffin, CSA, in Nashville, TN, 1905. Raymond Days It was Mother’s Day, and I was headed for Hinds County, Mississippi, coming up from The Big Easy via Bay Saint Louis on the Gulf Coast. I passed through Hattiesburg in the mid-afternoon where the two city police officers, one white and one African-American , had been gunned down the night before. Flags were at half-staff, but no other signs of disturbance were observable. The reason for the timing of this jaunt was the presence of a old shipmate who has kin in the town of Raymond, and some of the attendant family business to be done. I had my reasons to see the town, and this was an opportunity that I could not pass up. The other odd coincidence was the date- the battle had been fought on the 12th of May, and the meteorological conditions on the field for the visit would be very similar to the ones that the soldiers experienced 152 years ago. For those of you that care, the county was a product of western expansion in the first part of the new 19th Century, established in 1821 and named in honor of General Thomas Hinds. Specifically, I was headed to a Holiday Inn Express in Clinton, 7.1 miles from Raymond, since that is as close as the interstate and the modern version of civilization get to the place. -

The Commentaries of Chancellor James Kent and the Development of An

The Commentaries of Chancellor James Kent and the Development of an American Common Law, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ajlh/article/37/4/440/1789574 by guest on 30 September 2021 by CARL F. STYCHIN* The legal thought of Chancellor James Kent, as revealed in his four volume contribution to the American legal treatise literature, recently has resurfaced as a subject worthy of examination by legal historians. The importance of Kent as jurist and writer in the literary tradition of the legal treatise is beyond dispute. During his career on the bench, both on the New York Supreme Court and at Chancery, he brought an intellectual vigor to the Courts which helped shape the development of American jurisprudence. His Commentaries, which constituted a major step in the development of an indigenous treatise literature in America, enjoyed widespread popularity and went through fourteen editions. The purpose of this article is to focus on the importance of that literary contribution. The method adopted is a close textual examination to discern Kent's vision of the well ordered legal system as applied to America in the early years of the nineteenth century. James Kent was situated, with the other writers on the law of his age, in a unique position. Writing about the common law in post Revolutionary America, he was forced to redefine and redescribe its theo retical basis. Independence forced the rewriting of the story of the founda tions of the common law because, after the Revolution, its authority could no longer be grounded in the timelessness of English custom. -

Experiments in Government and the Essentials of the Constitution

Hein is Pleased to Introduce Another Classic Reprint by a Prominent American Lawyer and Statesman Experiments in Government and the Essentials of the Constitution By Elihu Root Elihu Root was an American lawyer and statesman and the 1912 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He was the prototype for the 20th century “wise man”, who shuttled between high-level government positions in Washington, D.C. and private-sector legal practice in New York City. Root served as the U.S. Secretary of War under William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt from 1899-1904, and the U.S. Secretary of State under Theodore Roosevelt from 1905-1909. This work is comprised of two lectures, given by Root, during the 1912-1913 Stafford Little Lectures Series at Princeton, which was initially known as the Stafford Little Lectureship on Public Affairs. The fund was founded in 1899 by Henry Stafford Little, who suggested that Grover Cleveland, ex-President of the United States, be invited to deliver before the students of the University ‘such lectures as he might be disposed to give from year to year.’ Mr. Cleveland was the Stafford Little lecturer until his death in 1908. Lecturers have included Theodore Roosevelt on “National Strength and International Duty” (1917-1918); Albert Einstein on “The Meaning of Relativity” (1920-1921); Henry L. Stimson on “Democracy and Nationalism in Europe” (1933-1934); Arnold Shoenberg on “Twelve-tone music composition” and Thurgood Marshall on “The Constitutional Rights of the Negro” (1963-1964). “The people of the United States appear now to have entered upon such a period of re-examination of their system of government. -

Louisville Kentucky During the First Year of the Civil

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY DURING THE FIRST YEAR OF THE CIVIL WAR BY WILLIAM G. EIDSON Nashville, Tennessee During the first eight months of 1861 the majority of Kentuckians favored neither secession from the Union nor coercion of the seceded states. It has been claimed that since the state opposed secession it was pro-Union, but such an assertion is true only in a limited sense. Having the same domestic institutions as the cotton states, Kentucky was con- cerned by the tension-filled course of events. Though the people of Kentucky had no desire to see force used on the southern states, neither did they desire to leave the Union or see it broken. Of course, there were some who openly and loudly advocated that their beloved commonwealth should join its sister states in the South. The large number of young men from the state who joined the Con- federate army attest to this. At the same time, there were many at the other extreme who maintained that Kentucky should join the northern states in forcibly preventing any state from withdrawing from the Union. Many of the moderates felt any such extreme action, which would result in open hostility between the two sections, would be especially harmful to a border state such as Kentucky. As the Daily Louisville Democrat phrased it, "No matter which party wins, we lose." 1 Thus moderates emphasized the economic advantages of a united country, sentimental attachment to the Union, and the hope of compromise. In several previous crises the country had found compromise through the leadership of great Kentuckians. -

FOR the RECORDS Common Legal Doctrine in the Colonial and Early United States

VOL. 11, NO. 9 — SEPTEMBER 2019 From the dower release in a deed acknowledgement in Frederick Co., Maryland: “Louisa wife of the said John Weaver being examined apart From her said husband relinquished her right of Dower to the said Lott or portion of ground and Acknowledged that she did freely and Willingly without being Induced thereto by coercion of her said Husband or for Fear of his Displeasure.” Source: Frederick County, Maryland. Liber K: 109. John Weaver to Michael Hare, 24th October 1775. Office of Recorder of Deeds, Frederick County, Maryland. Adopted from English common law, coverture was the FOR THE RECORDS common legal doctrine in the colonial and early United States. Depending on the colony (state or territory), the “Freely and without coercion”— practice adopted a more strict (Massachusetts), progres- Deed records under coverture sive (middle colonies) or conservative (southern colonies) approach to the rights of a feme covert and her right to “Coverture” (sometimes spelled “couverture”) was a legal property. doctrine whereby a married woman’s status as “feme cov- ert” (a married woman) removed her rights and obligations The southern colonies “accepted the existence of coer- and transferred them to her husband. This legal principle cion” while “effectively … [keeping] women in a subser- created records that can reveal information about ancestors vient position”1 by developing overprotective laws that and uncover clues that can break through brick walls. treated femes covert as helpless. These colonies empha- sized precision in record keeping ensuring the certainty of Background land title. A feme covert had no rights to own property, litigate, own a business.