Where Mcgavock Fell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Record of the Organizations Engaged in the Campaign, Siege, And

College ILttirarjj FROM THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ' THROUGH £> VICKSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK COMMISSION. RECORD OF THE ORGANIZATIONS ENGAGED IN THE CAMPAIGN, SIEGE, AND DEFENSE OF VICKSBURG. COMPILED FROM THE OFFICIAL RECORDS BY jomsr s. KOUNTZ, SECRETARY AND HISTORIAN OF THE COMMISSION. WASHINGTON: GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE. 1901. PREFACE. The Vicksburg campaign opened March 29, 1863, with General Grant's order for the advance of General Osterhaus' division from Millikens Bend, and closed July 4^, 1863, with the surrender of Pem- berton's army and the city of Vicksburg. Its course was determined by General Grant's plan of campaign. This plan contemplated the march of his active army from Millikens Bend, La. , to a point on the river below Vicksburg, the running of the batteries at Vicksburg by a sufficient number of gunboats and transports, and the transfer of his army to the Mississippi side. These points were successfully accomplished and, May 1, the first battle of the campaign was fought near Port Gibson. Up to this time General Grant had contemplated the probability of uniting the army of General Banks with his. He then decided not to await the arrival of Banks, but to make the cam paign with his own army. May 12, at Raymond, Logan's division of Grant's army, with Crocker's division in reserve, was engaged with Gregg's brigade of Pemberton's army. Gregg was largely outnum bered and, after a stout fight, fell back to Jackson. The same day the left of Grant's army, under McClernand, skirmished at Fourteen- mile Creek with the cavalry and mounted infantry of Pemberton's army, supported by Bowen's division and two brigades of Loring's division. -

American Civil War

American Civil War Major Battles & Minor Engagements 1861-1865 1861 ........ p. 2 1862 ........ p. 4 1863 ........ p. 9 1864 ........ p. 13 1865 ........ p. 19 CIVIL WAR IMPRESSIONIST ASSOCIATION 1 Civil War Battles: 1861 Eastern Theater April 12 - Battle of Fort Sumter (& Fort Moultie), Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. The bombardment/siege and ultimate surrender of Fort Sumter by Brig. General P.G.T. Beauregard was the official start of the Civil War. https://www.nps.gov/fosu/index.htm June 3 - Battle of Philippi, (West) Virginia A skirmish involving over 3,000 soldiers, Philippi was the first battle of the American Civil War. June 10 - Big Bethel, Virginia The skirmish of Big Bethel was the first land battle of the civil war and was a portent of the carnage that was to come. July 11 - Rich Mountain, (West) Virginia July 21 - First Battle of Bull Run, Manassas, Virginia Also known as First Manassas, the first major engagement of the American Civil War was a shocking rout of Union soldiers by confederates at Manassas Junction, VA. August 28-29 - Hatteras Inlet, North Carolina September 10 - Carnifax Ferry, (West) Virginia September 12-15 - Cheat Mountain, (West) Virginia October 3 - Greenbrier River, (West) Virginia October 21 - Ball's Bluff, Virginia October 9 - Battle of Santa Rosa Island, Santa Rosa Island (Florida) The Battle of Santa Rosa Island was a failed attempt by Confederate forces to take the Union-held Fort Pickens. November 7-8 - Battle of Port Royal Sound, Port Royal Sound, South Carolina The battle of Port Royal was one of the earliest amphibious operations of the American Civil War. -

Union Treatment of Civilians and Private Property in Mississippi, 1862-1865: an Examination of Theory and Practice

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1972 Union Treatment of Civilians and Private Property in Mississippi, 1862-1865: An Examination of Theory and Practice Nathaniel A. Jobe College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Military and Veterans Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Jobe, Nathaniel A., "Union Treatment of Civilians and Private Property in Mississippi, 1862-1865: An Examination of Theory and Practice" (1972). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624787. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-xjj9-r068 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNION TREATMENT OF n CIVILIANS AND PRIVATE PROPERTY IN MISSISSIPPI, 1862-1865* AN EXAMINATION OF THEORY AND PRACTICE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts *>y Nathaniel A, Jobe, Jr 1972 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, August 1972 Ludwell son, chairman M. B, Coyner LdoxKtr Helen C, Walker ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . ............ .................... iv ABSTRACT.............. v INTRODUCTION................ 2 CHAPTER I. THE RULES OF WAR ..................... k CHAPTER II. -

The Louisiana True Delta

The Louisiana True Delta Newsletter of the Louisiana Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans Second Quarter – April 2018 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ~Candidate Announcements & Reunion Information Inside~ Compatriots: Spring is finally here, and we can begin getting over our “winter cabin fever”. Reenactments and other activities will be in abundance. On the calendar are three reenactments. Pleasant Hill will be held on April 13-15, Jackson Crossroads on April 20-22 and Jefferson, TX on May 4-6. On April 28 th , there will be a Memorial Service at the Confederate Cemetery at Keatchie, LA and a Memorial Dedication in Vicksburg, MS at the Cedar Hill Cemetery at 10:30 am. In Vicksburg, tombstones for 50 Confederate Soldiers will be placed in the Cemetery honoring soldiers who died at the Battle of Raymond. Most of these men were from Louisiana. Mark your calendar for the Louisiana Division 2018 Reunion to be held at the Lafayette Hilton Garden Inn on May 18-19. The DEC meeting will be held on Friday the 18 th (time TBA). The National Reunion will be held on July 19-21 in Franklin, TN. This is an election year for both state and national offices, so please try to attend. Also, in conjunction with the National Reunion, a ribbon cutting for our new SCV Museum will be held in Elm Springs, TN on Wednesday, July 18 th from 10 to 11 am. We hope to see you at these very important events!!!! The Stephen D. Lee Seminar that was held in Shreveport on February 17 th was a big success and possibly had the largest in attendance so far. -

The Journal of Mississippi History

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXX Spring/Summer 2018 No. 1 and No. 2 CONTENTS Introduction: How Did the Grant Material Come to Mississippi? 1 By John F. Marszalek “To Verify From the Records Every Statement of Fact Given”: The Story of the Creation of The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant: The Complete Annotated Edition 7 By David S. Nolen and Louie P. Gallo “I am Thinking Seriously of Going Home”: Mississippi’s Role in the Most Important Decision of Ulysses S. Grant’s Life 21 By Timothy B. Smith Applicability in the Modern Age: Ulysses S. Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign 35 By Terrence J. Winschel COVER IMAGE — Ulysses S. Grant (circa April 1865), courtesy of the Bultema-Williams Collection of Ulysses S. Grant Photographs and Prints from the Frank and Virginia Williams Collection of Lincolniana, Mississippi State University Libraries. Hiram R. Revels, Ulysses S. Grant, Party Politics, and the Annexation of Santo Domingo 49 By Ryan P. Semmes Mississippi’s Most Unlikely Hero: Press Coverage of 67 Ulysses S. Grant, 1863-1885 By Susannah J. Ural The Journal of Mississippi History (ISSN 0022-2771) is published quarterly by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 200 North St., Jackson, MS 39201, in cooperation with the Mississippi Historical Society as a benefit of Mississippi Historical Society membership. Annual memberships begin at $25. Back issues of the Journal sell for $7.50 and up through the Mississippi Museum Store; call 601-576-6921 to check availability. The Journal of Mississippi History is a juried journal. Each article is reviewed by a specialist scholar before publication. -

Long March to Vicksburg: Soldier and Civilian Interaction In

LONG MARCH TO VICKSBURG: SOLDIER AND CIVILIAN INTERACTION IN THE VICKSBURG CAMPAIGN by STEVEN NATHANIEL DOSSMAN Bachelor of Arts, 2006 McMurry University Abilene, Texas Master of Arts, 2008 Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of AddRan College of Liberal Arts Texas Christian University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2012 Copyright by Steven Nathaniel Dossman 2012 CONTENTS I. “Hunger is more powerful than powder and lead”……………………………… 1 II. “Devastation marked the whole path of the army”………………………………39 III. “This is a cruel warfare”……………..………………………………………......63 IV. “We were all caught in a rat-hole”……………………………………………….94 V. “A death blow fell upon the Confederacy”………………………………………129 VI. “Nothing is left between Vicksburg & Jackson”………………………………....164 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………………………………………………………………. 202 ii CHAPTER 1 “HUNGER IS MORE POWERFUL THAN POWDER AND LEAD” The campaign for Vicksburg, Mississippi, determined the survival of the Confederacy. Successful secession depended on Confederate control of the Mississippi River, the vast waterway historian Terrence J. Winschel acknowledged as “the single most important economic feature of the continent, the very lifeblood of America.”1 The river separated the South into two distinct sections, presenting an ideal invasion route for northern armies, as General-in-Chief Winfield Scott proposed in his famous “Anaconda Plan.” Union control of the Mississippi would prevent vital supply and manpower transport from one bank to another, reducing the Trans- Mississippi Theater to a detached region of the South powerless to influence the outcome of the war. As the Federal blockade tightened around southern ports, the European trade from Matamoras, Mexico into Texas became increasingly important to the Confederate war effort, and a division of the South would deny these crucial supplies to hard pressed armies in Tennessee and Virginia.2 As President Abraham Lincoln observed in 1862, “Vicksburg is the key. -

Vicksburg, Pt. 2

“… try, try again!"! Vicksburg campaign success John F. Allen, Jr.! 2 October 2014 Presented to the Camp Olden Civil War Round Table, Hamilton, NJ Images in this presentation were primarily downloaded from the internet. Unsuccessful attempts were made to contact the webmaster for use of photographs of modern day views. “Distractions” and Port Gibson maps used are from Bearss (1985); map of Grierson’s Raid from Brown (1981), both cited below. Text was gleaned from the following outstanding resources: Bearss, Edwin Cole (1985): “The Vicksburg Campaign: Volume 2 - Grant Strikes A Fatal Blow” and “Volume 3 - Unvexed To The Sea”, published by Morningside House, Inc., Dayton, OH Brown, D. Alexander (1981): “Grierson’s Raid”, published by Morningside House, Inc., Dayton, OH Vicksburg's importance • Rail head for the Trans- Mississippi • First high point on the Mississippi River downriver of Memphis • Lincoln (1862): “See what a lot of Memphis land these fellows hold, of which Vicksburg is the key… The war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket.” Vicksburg • Halleck to Grant March 20, 1863: “…the opening of the Mississippi Port Hudson River will be of more advantage to us than forty Richmonds.” Grant's failures • Mississippi Central approach (Nov - Dec 1862) • Chickasaw Bayou (Dec 1862) X • Yazoo Pass (Feb - Apr ’63) X • Steele's Bayou (Mar ’63) X • X Grant's Canal (Jan - Mar ’63) X Views of Grant • Rumored intemperance • Poor troop handling at Shiloh • Five failed attempts to take Vicksburg • John Nicolay to wife: "Grant's attempt to take Vicksburg looks to me very much like a total failure..." • Viewed as the equal of McClellan, Burnside, Fremont and Buell. -

Harvard Confederates Who Fell in the Civil

Advocates for Harvard ROTC HARVARD CONFEDERATES H Total served Killed in Action Died by disease & accidents Harvard College* 145 19 5 (all by disease) Harvard Law School 227 33 7 (all by accidents) Harvard Medical School 3 0 0 Miscellaneous /unknown NA 12 ? Total 357 64 12 *Including the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard The above total of Harvard alumni serving in the Confederate military included five major generals and eight brigadier generals, three of which were killed in battle. In addition, there were 29 Harvard alumni serving as civilians in the Confederate government. It surprises some that 28% of all Harvard alumni who served in the Civil War fought for the South but Harvard Confederates represent 44% of the sons of Harvard killed in action during this conflict. As result among Harvard alumni, Confederate military losses were 21% compared with a 10% casualty rate for the Union Army. Confederate soldiers were forced by the statutes of the Congress of the Southern Confederacy to serve throughout the war, regardless of the terms of their enlistment or commission, which was not the case on the Union side. Thus, Confederate soldiers generally participated in more engagements than the Union troops. Thus, Confederate soldiers generally participated in more engagements than the Union troops. Among the Confederate casualties from Harvard were: • An officer who was killed in the same battle where his brother fought as an officer in the Union Army • A brigadier general who was the brother in law of Abraham Lincoln. As expected, most of the Harvard alumni killed in the service of the Confederacy were born and raised in the Southern states. -

Reminiscences Campaigns Against Vicksburg

REMINISCENCES OF THE CAMPAIGNS AGAINST VICKSBURG BY GENERAL JOHN B. SANBORN (1879) Foreword By Douglas A. Hedin Editor, MLHP Historian James M. McPherson writes of the fall of Vicksburg: All through June, Union troops had dug approaches toward Confederate lines in a classic siege operation. They also tunneled under rebel defenses. To show what they could do, northern engineers exploded mines and blew holes in southern lines on June 15 and July 1, but Confederate in- fantry closed the breaches. The Yankees readied a bigger mine to be set off July 6 and followed by a full-scale assault. But before then it was all over. Literally starving, "Many Soldiers" addressed a letter to [Confederate General] Pemberton on June 28: “If you can't feed us, you had better surrender, horrible as the idea is, than suffer this noble army to disgrace themselves by desertion. This army is now ripe for mutiny, unless it can be fed." Pemberton consulted his division commanders, who assured him that their sick and malnourished men could not attempt a breakout attack. On July 3, Pemberton asked Grant for terms. Living up to his Donelson reputation, Grant at first insisted on unconditional surrender. But after reflecting on the task of shipping 30,000 captives north to prison camps when he needed all his transport for further operations, Grant offered to parole the prisoners. With good reason he expected that many of them disillusioned by suffering and surrender, would scatter to their homes and carry the contagion of defeat with them. The Fourth of July 1863 was the most memorable Independence Day in American history since that first one four score and seven yeas earlier. -

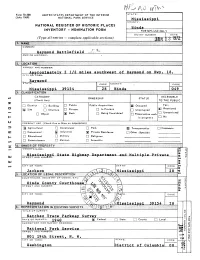

Ilillilllliiililiiil:: OWNER's NAME: Mississippi State Highway Department and Multiple Private

A Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Mississippi COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Hinds INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY EN TRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) 1972" COMMON: AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: Approximately 2 1/2 miles southwest of Raymond on Hwy. 18 CITY OR TOWN: Raymond STATE COUNTY: 28 Einds 049 Illllllllllliillii; CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District Q Building Public Public Acquisition: |Xl Occupied Yes: jjj[] Restricted Site Q Structure Private || In Process II Unoccupied Q] Unrestricted D Object | | Being Considered I | Preservation work in progress D No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) [3^ Agricultural | | Government D Park Transportation I I Comments P~l Commercial ^] Industrial [jj] Private Residence Other (Specify) [ | Educational Q Military I | Religious r~l Entertainment || Museum [ | Scientific Ilillilllliiililiiil:: OWNER'S NAME: Mississippi State Highway Department and Multiple Private COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: A~>^ / /<V Einds County Courtkous/e^ STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: .i88j.88..^ TITLE OF SURVEY: Natchez Trace Parkvav Survey DATE OF SURVEY: 1940 Federal State | | County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: National Park Service STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Washington district of Columbia (Check One) | | Excellent Good D PI Deteriorated [~] Ruins [ | Unexposed CONDITION (Check One; (Check One) Altered Q Unaltered Moved SI Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The site of the Battle of Raymond is changed in appearance by the paved old Highway 18 and the new Highway 18 running lengthways through the middle of the battlefield and across Fourteen Mile Creek. -

Historical Review

HISTORICAL REVIEW See Page I ublished Quar OCTOBER, 195! tate Historical Society of Missouri COLUMBIA, MISSOURI THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI The State Historical Society of Missouri, heretofore organized under the laws of this State, shall be the trustee of this State.—Laws of Missouri, 1899, R. S. of Mo., 1949, Chapter 183. OFFICERS 1953-1956 L. M. WHITE, Mexico, President GEORGE ROBB ELLISON, Maryville, First Vice-President RUSH H. LIMBAUGH, Cape Girardeau, Second Vice-President HENRY A. BUNDSCHU, Independence, Third Vice-President BARTLETT BODER, St. Joseph, Fourth Vice-President RAY V. DENSLOW, Trenton, Fifth Vice-President W. C. HEWITT, Shelbyville, Sixth Vice-President R. B. PRICE, Columbia, Treasurer FLOYD C. SHOEMAKER, Columbia, Secretary and Librarian TRUSTEES Permanent Trustees, Former Presidents of the Society ALLEN MCREYNOLDS, Carthage E. E. SWAIN, Kirksville GEORGE A. ROZIER, Jefferson City G. L. ZWICK, St. Joseph WILLIAM SOUTHERN, JR., Independence Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1955 CHESTER A. BRADLEY, Kansas City GEORGE H. SCRUTON, Sedalia GEORGE ROBB ELLISON, Maryville JAMES TODD, Moberly ALFRED O. FUERBRINGER, St. Louis T. BALLARD WATTERS, Marshfield FRANK L. MOTT, Columbia L. M. WHITE, Mexico Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1956 F. C. BARNHILL, Marshall RALPH P. JOHNSON, Osceola FRANK P. BRIGGS, Macon *E. LANSING RAY, St. Louis W. C. HEWITT, Shelbyville ALBERT L. REEVES, Kansas City STEPHEN B. HUNTER, Cape Girardeau ROY D. WILLIAMS, Boonville Term Expires at Annual Meeting, 1957 RALPH P. BIEBER, St. Louis L. E. MEADOR, Springfield ARTHUR V. BURROWES, St. Joseph JOSEPH H. MOORE, Charleston WM. P. ELMER, Salem ISRAEL A. SMITH, Independence LAURENCE J. -

Vicksburg Sesquicentennial Commemoration: Signature Event

ancestors fought in the May 16, 1863 battle. You must be present to receive the medallion. Vicksburg Campaign Batt le Commemorations Following the program, Lunch on the Lawn will be served ($10.00 a plate). Highlights of the afternoon will feature a stroll to the “Hill of Death” followed by a reenactment and a historic April 19-20: Vicksburg Campaign Battle of Port Gibson Sesquicentennial Commemoration. marker dedication at the Champion Hill Crossroads. Admission is free. Visit www.battle- The Battle of Port Gibson Commemoration includes living history presentations, a cemetery ofchampionhill.org for more information. tour and a battlefield tour in the city that was “too beautiful to burn.” A Living History will be presented at Grand Gulf Military Monument throughout the weekend. “Whispers in the Cedars,” May 19: Commemoration of First Assault on Vicksburg. First Assault programs begin at a tour of Wintergreen Cemetery featuring the graves of local people who were active partic- 10:00 am with the Confederate perspective at Stop 12, Stockade Redan in the Vicksburg ipants in the War Between the States, will take place at 7:00 pm on Friday, April 19 and at National Military Park. The Union perspective begins at 1:00 pm at Stop 5, Stockade Redan 5:00 pm and 7:00 pm on Saturday, April 20. A battlefield tour led by Brig. Gen. Parker Hills Attack. For more information call 601-636-0583 or visit www.nps.gov/vick. will take place from 10:00 am until noon on Saturday. For more information contact Pastor Michael Herrin at First Presbyterian Church of Port Gibson at [email protected].