Saber and Scroll Journal Volume VI Issue I Winter 2017 Saber And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apus Constellation Visible at Latitudes Between +5° and -90°

Apus Constellation Visible at latitudes between +5° and -90°. Best visible at 21:00 (9 p.m.) during the month of July. Apus is a small constellation in the southern sky. It represents a bird-of-paradise, and its name means "without feet" in Greek because the bird-of-paradise was once wrongly believed to lack feet. First depicted on a celestial globe by Petrus Plancius in 1598, it was charted on a star atlas by Johann Bayer in his 1603 Uranometria. The French explorer and astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille charted and gave the brighter stars their Bayer designations in 1756. The five brightest stars are all reddish in hue. Shading the others at apparent magnitude 3.8 is Alpha Apodis, an orange giant that has around 48 times the diameter and 928 times the luminosity of the Sun. Marginally fainter is Gamma Apodis, another ageing giant star. Delta Apodis is a double star, the two components of which are 103 arcseconds apart and visible with the naked eye. Two star systems have been found to have planets. Apus was one of twelve constellations published by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman who had sailed on the first Dutch trading expedition, known as the Eerste Schipvaart, to the East Indies. It first appeared on a 35-cm diameter celestial globe published in 1598 in Amsterdam by Plancius with Jodocus Hondius. De Houtman included it in his southern star catalogue in 1603 under the Dutch name De Paradijs Voghel, "The Bird of Paradise", and Plancius called the constellation Paradysvogel Apis Indica; the first word is Dutch for "bird of paradise". -

Naming the Extrasolar Planets

Naming the extrasolar planets W. Lyra Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, K¨onigstuhl 17, 69177, Heidelberg, Germany [email protected] Abstract and OGLE-TR-182 b, which does not help educators convey the message that these planets are quite similar to Jupiter. Extrasolar planets are not named and are referred to only In stark contrast, the sentence“planet Apollo is a gas giant by their assigned scientific designation. The reason given like Jupiter” is heavily - yet invisibly - coated with Coper- by the IAU to not name the planets is that it is consid- nicanism. ered impractical as planets are expected to be common. I One reason given by the IAU for not considering naming advance some reasons as to why this logic is flawed, and sug- the extrasolar planets is that it is a task deemed impractical. gest names for the 403 extrasolar planet candidates known One source is quoted as having said “if planets are found to as of Oct 2009. The names follow a scheme of association occur very frequently in the Universe, a system of individual with the constellation that the host star pertains to, and names for planets might well rapidly be found equally im- therefore are mostly drawn from Roman-Greek mythology. practicable as it is for stars, as planet discoveries progress.” Other mythologies may also be used given that a suitable 1. This leads to a second argument. It is indeed impractical association is established. to name all stars. But some stars are named nonetheless. In fact, all other classes of astronomical bodies are named. -

___... -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

__ __ _____ _____ _____ _____ ____ _ __ / / / / /_ _/ / ___/ /_ _/ / __ ) / _ \ | | / / / /__/ / / / ( ( / / / / / / / /_) / | |/ / / ___ / / / \ \ / / / / / / / _ _/ | _/ / / / / __/ / ____) ) / / / /_/ / / / \ \ / / /_/ /_/ /____/ /_____/ /_/ (_____/ /_/ /_/ /_/ _____ _____ _____ __ __ _____ / __ ) / ___/ /_ _/ / / / / / ___/ / / / / / /__ / / / /__/ / / /__ / / / / / ___/ / / / ___ / / ___/ / /_/ / / / / / / / / / / /___ (_____/ /_/ /_/ /_/ /_/ /_____/ _____ __ __ _____ __ __ ____ _____ / ___/ / / / / /_ _/ / / / / / _ \ / ___/ / /__ / / / / / / / / / / / /_) / / /__ / ___/ / / / / / / / / / / / _ _/ / ___/ / / / /_/ / / / / /_/ / / / \ \ / /___ /_/ (_____/ /_/ (_____/ /_/ /_/ /_____/ A TIMELINE OF THE MULTIVERSE Version 1.21 By K. Bradley Washburn "The Historian" ______________ | __ | | \| /\ / | | |/_/ / | | |\ \/\ / | | |_\/ \/ | |______________| K. Bradley Washburn HISTORY OF THE FUTURE Page 2 of 2 FOREWARD Relevant Notes WARNING: THIS FILE IS HAZARDOUS TO YOUR PRINTER'S INK SUPPLY!!! [*Story(Time Before:Time Transpired:Time After)] KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS AS--The Amazing Stories AST--Animated Star Trek B5--Babylon 5 BT--The Best of Trek DS9--Deep Space Nine EL--Enterprise Logs ENT--Enterprise LD--The Lives of Dax NE--New Earth NF--New Frontier RPG--Role-Playing Games S.C.E.--Starfleet Corps of Engineers SA--Starfleet Academy SNW--Strange New Worlds sQ--seaQuest ST--Star Trek TNG--The Next Generation TNV--The New Voyages V--Voyager WLB—Gateways: What Lay Beyond Blue italics - Completely canonical. Animated and live-action movies, episodes, and their novelizations. Green italics - Officially canonical. Novels, comics, and graphic novels. Red italics – Marginally canonical. Role-playing material, source books, internet sources. For more notes, see the AFTERWORD K. Bradley Washburn HISTORY OF THE FUTURE Page 3 of 3 TIMELINE circa 13.5 billion years ago * The Big Bang. -

Educator's Guide: Orion

Legends of the Night Sky Orion Educator’s Guide Grades K - 8 Written By: Dr. Phil Wymer, Ph.D. & Art Klinger Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………....3 Constellations; General Overview……………………………………..4 Orion…………………………………………………………………………..22 Scorpius……………………………………………………………………….36 Canis Major…………………………………………………………………..45 Canis Minor…………………………………………………………………..52 Lesson Plans………………………………………………………………….56 Coloring Book…………………………………………………………………….….57 Hand Angles……………………………………………………………………….…64 Constellation Research..…………………………………………………….……71 When and Where to View Orion…………………………………….……..…77 Angles For Locating Orion..…………………………………………...……….78 Overhead Projector Punch Out of Orion……………………………………82 Where on Earth is: Thrace, Lemnos, and Crete?.............................83 Appendix………………………………………………………………………86 Copyright©2003, Audio Visual Imagineering, Inc. 2 Legends of the Night Sky: Orion Educator’s Guide Introduction It is our belief that “Legends of the Night sky: Orion” is the best multi-grade (K – 8), multi-disciplinary education package on the market today. It consists of a humorous 24-minute show and educator’s package. The Orion Educator’s Guide is designed for Planetarians, Teachers, and parents. The information is researched, organized, and laid out so that the educator need not spend hours coming up with lesson plans or labs. This has already been accomplished by certified educators. The guide is written to alleviate the fear of space and the night sky (that many elementary and middle school teachers have) when it comes to that section of the science lesson plan. It is an excellent tool that allows the parents to be a part of the learning experience. The guide is devised in such a way that there are plenty of visuals to assist the educator and student in finding the Winter constellations. -

Pacifica Military History Sample Chapters 1

Pacifica Military History Sample Chapters 1 WELCOME TO Pacifica Military History FREE SAMPLE CHAPTERS *** The 28 sample chapters in this free document are drawn from books written or co-written by noted military historian Eric Hammel. All of the books are featured on the Pacifca Military History website http://www.PacificaMilitary.com where the books are for sale direct to the public. Each sample chapter in this file is preceded by a line or two of information about the book's current status and availability. Most are available in print and all the books represented in this collection are available in Kindle editions. Eric Hammel has also written and compiled a number of chilling combat pictorials, which are not featured here due to space restrictions. For more information and links to the pictorials, please visit his personal website, Eric Hammel’s Books. All of Eric Hammel's books that are currently available can be found at http://www.EricHammelBooks.com with direct links to Amazon.com purchase options, This html document comes in its own executable (exe) file. You may keep it as long as you like, but you may not print or copy its contents. You may, however, pass copies of the original exe file along to as many people as you want, and they may pass it along too. The sample chapters in this free document are all available for free viewing at Eric Hammel's Books. *** Copyright © 2009 by Eric Hammel All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

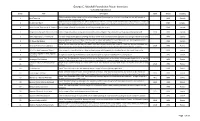

GCMF Poster Inventory

George C. Marshall Foundation Poster Inventory Compiled August 2011 ID No. Title Description Date Period Country A black and white image except for the yellow background. A standing man in a suit is reaching into his right pocket to 1 Back Them Up WWI Canada contribute to the Canadian war effort. A black and white image except for yellow background. There is a smiling soldier in the foreground pointing horizontally to 4 It's Men We Want WWI Canada the right. In the background there is a column of soldiers march in the direction indicated by the foreground soldier's arm. 6 Souscrivez à L'Emprunt de la "Victoire" A color image of a wide-eyed soldier in uniform pointing at the viewer. WWI Canada 2 Bring Him Home with the Victory Loan A color image of a soldier sitting with his gun in his arms and gear. The ocean and two ships are in the background. 1918 WWI Canada 3 Votre Argent plus 5 1/2 d'interet This color image shows gold coins falling into open hands from a Canadian bond against a blue background and red frame. WWI Canada A young blonde girl with a red bow in her hair with a concerned look on her face. Next to her are building blocks which 5 Oh Please Do! Daddy WWI Canada spell out "Buy me a Victory Bond" . There is a gray background against the color image. Poster Text: In memory of the Belgian soldiers who died for their country-The Union of France for Belgium and Allied and 7 Union de France Pour La Belqiue 1916 WWI France Friendly Countries- in the Church of St. -

Sydney Observatory Night Sky Map September 2012 a Map for Each Month of the Year, to Help You Learn About the Night Sky

Sydney Observatory night sky map September 2012 A map for each month of the year, to help you learn about the night sky www.sydneyobservatory.com This star chart shows the stars and constellations visible in the night sky for Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Canberra, Hobart, Adelaide and Perth for September 2012 at about 7:30 pm (local standard time). For Darwin and similar locations the chart will still apply, but some stars will be lost off the southern edge while extra stars will be visible to the north. Stars down to a brightness or magnitude limit of 4.5 are shown. To use this chart, rotate it so that the direction you are facing (north, south, east or west) is shown at the bottom. The centre of the chart represents the point directly above your head, called the zenith, and the outer circular edge represents the horizon. h t r No Star brightness Moon phase Last quarter: 08th Zero or brighter New Moon: 16th 1st magnitude LACERTA nd Deneb First quarter: 23rd 2 CYGNUS Full Moon: 30th rd N 3 E LYRA th Vega W 4 LYRA N CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES BOOTES VULPECULA SAGITTA PEGASUS DELPHINUS Arcturus Altair EQUULEUS SERPENS AQUILA OPHIUCHUS SCUTUM PISCES Moon on 23rd SERPENS Zubeneschamali AQUARIUS CAPRICORNUS E SAGITTARIUS LIBRA a Saturn Centre of the Galaxy Antares Zubenelgenubi t s Antares VIRGO s t SAGITTARIUS P SCORPIUS P e PISCESMICROSCOPIUM AUSTRINUS SCORPIUS Mars Spica W PISCIS AUSTRINUS CORONA AUSTRALIS Fomalhaut Centre of the Galaxy TELESCOPIUM LUPUS ARA GRUSGRUS INDUS NORMA CORVUS INDUS CETUS SCULPTOR PAVO CIRCINUS CENTAURUS TRIANGULUM -

De Grave & Fransen. Carideorum Catalogus

De Grave & Fransen. Carideorum catalogus (Crustacea: Decapoda). Zool. Med. Leiden 85 (2011) 407 Fig. 48. Synalpheus hemphilli Coutière, 1909. Photo by Arthur Anker. Synalpheus iphinoe De Man, 1909a = Synalpheus Iphinoë De Man, 1909a: 116. [8°23'.5S 119°4'.6E, Sapeh-strait, 70 m; Madura-bay and other localities in the southern part of Molo-strait, 54-90 m; Banda-anchorage, 9-36 m; Rumah-ku- da-bay, Roma-island, 36 m] Synalpheus iocasta De Man, 1909a = Synalpheus Iocasta De Man, 1909a: 119. [Makassar and surroundings, up to 32 m; 0°58'.5N 122°42'.5E, west of Kwadang-bay-entrance, 72 m; Anchorage north of Salomakiëe (Damar) is- land, 45 m; 1°42'.5S 130°47'.5E, 32 m; 4°20'S 122°58'E, between islands of Wowoni and Buton, northern entrance of Buton-strait, 75-94 m; Banda-anchorage, 9-36 m; Anchorage off Pulu Jedan, east coast of Aru-islands (Pearl-banks), 13 m; 5°28'.2S 134°53'.9E, 57 m; 8°25'.2S 127°18'.4E, an- chorage between Nusa Besi and the N.E. point of Timor, 27-54 m; 8°39'.1 127°4'.4E, anchorage south coast of Timor, 34 m; Mid-channel in Solor-strait off Kampong Menanga, 113 m; 8°30'S 119°7'.5E, 73 m] Synalpheus irie MacDonald, Hultgren & Duffy, 2009: 25; Figs 11-16; Plate 3C-D. [fore-reef (near M1 chan- nel marker), 18°28.083'N 77°23.289'W, from canals of Auletta cf. sycinularia] Synalpheus jedanensis De Man, 1909a: 117. [Anchorage off Pulu Jedan, east coast of Aru-islands (Pearl- banks), 13 m] Synalpheus kensleyi (Ríos & Duffy, 2007) = Zuzalpheus kensleyi Ríos & Duffy, 2007: 41; Figs 18-22; Plate 3. -

PART ONE MANDEGUSU Mandegusu—'Tour Districts"

PART ONE MANDEGUSU Mandegusu—'Tour Districts" The indigenous name for Simbo "starting long ago". Each district was associated with a lineage. The four districts were Karivara, Narovo, Nusa Simbo and Ove. The four lineages were Karivara, Vunagugusu, Nusa Simbo and Ove. They had different lineages inside them— thus Ove had Narilulubi, [a different] Vunagugusu and others. Like that. Sometimes they had small wars between them - if someone was murdered or raped or something like that. But they settled those with [exchanges of clamshell] rings before they got big. True wars were against outsiders in Santa Isabel, Choiseul, Guadalcanal, those faraway places. The district and the leaders co-operated to fight those wars. It was like that starting long ago until the peace came down. Rona Barogoso. CHAPTER ONE PANA TOTOSO KAME RANE IN THE TIME OF LONG AGO Pace 'classical' anthropological models of later vintage, their chiefdoms were not islands unto themselves. Nor did they suffer from 'closed predicaments',... have 'cold' cultures ..., or occupy the timeless Lebenswelt that social scientists would ... attribute to them by contrast to ourselves ... Quite the opposite: ... [they] were caught up in complex regional relations, subde political and material processes and vital cultural discourses. Comaroff & Comaroff, 1991: 126 [references in original omitted] Although the ultimately exploitative character of the global economy can hardly be overlooked, an analysis which makes dominance and extraction central to intersocial exchange from its beginnings will frequently misconstrue power relations which did not, in fact, entail the subordination of native people. N.Thomas, 1991:83-84 Totoso Kame Rane—Time of One Day Kame Rane has many referents, but always implies some time in the past. -

Journey to Italy Press Notes

Janus Films Presents Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy NEW DCP RESTORATION! http://www.janusfilms.com/journey Director: Roberto Rossellini JANUS FILMS Country: Italy Sarah Finklea Language: English Ph: 212-756-8715 Year: 1954 [email protected] Run time: 86 minutes B&W / 1.37 / Mono JOURNEY TO ITALY SYNOPSIS Among the most influential films of the postwar era, Roberto Rossellini’s Journey to Italy charts the declining marriage of a British couple (Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders) on a trip in the countryside near Naples. More than just an anatomy of a relationship, Rossellini’s masterpiece is a heartrending work of emotional transcendence and profound spirituality. Considered an ancestor of the existential works of Michelangelo Antonioni; hailed as a groundbreaking work of modernism by the critics of Cahiers du cinéma; and named by Martin Scorsese as one of his favorite films, Journey to Italy is a breathtaking cinematic landmark. Janus Films is proud to present a new, definitive restoration of the essential English-language version of the film, featuring Bergman and Sanders voicing their own dialogue. JOURNEY TO ITALY ABOUT THE ROSSELLINI PROJECT The Rossellini Project continues the initiative created by Luce Cinecittà, Cineteca di Bologna, CSC-Cineteca Nazionale, and the Coproduction Office as a means of rediscovering and showcasing the work of a reference point in the art of cinema: Roberto Rossellini. Three of Italian cinema’s great institutions and an influential international production house have joined forces to restore a central and fundamental part of the filmmaker’s filmography, as well as promote and distribute it on an international level. -

Victory in the Pacific Battle of Guadalcanal

• War in the Pacific Series • Bringing history to life Victory in the Pacific Battle of Guadalcanal Brisbane • Guadalcanal • Tulagi August 1–9, 2022 Featuring world-renowned naval historian and author James D. Hornfischer Book early and save! Visit ww2museumtours.org for details. Dear friend of the Museum and fellow traveler, THE NATIONAL WWII MUSEUM I am honored to join The National WWII Museum on this tour of Guadalcanal, EDUCATIONAL TRAVEL PROGRAM the target of the first major Allied offensive of World War II. With its position in the South Pacific, Guadalcanal was an ideal location for a Japanese airfield that could threaten vital US sea lanes to Australia. Seeing the threat, the American high command resolved at once that the airfield must never become operational. On August 7, 1942, Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift’s First Marine Division carried out the first American amphibious invasion of the war, with barely a shot being fired. As we will see on the tour, the anticlimax of the landings suggested none of the hell that lay ahead. Subjected to fierce counterattacks and suicidal charges by Japanese soldiers, the Marines on Guadalcanal fought tenaciously. Traversing the terrain of Bloody Ridge, standing on the banks of the Tenaru River, and investigating the jungle terrain, we will gain a renewed appreciation for what our men achieved. Meanwhile, in the narrow straits of the Slot, the US Navy began a death match against the Japanese fleet to defend the Marine lodgment. As I wrote in my book Travel to Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal, the four nighttime surface actions fought in the waters off Guadalcanal claimed the lives of three sailors for every man who died in battle ashore. -

The Florida Historical Quarterly

COVER The Gainesville Graded and High School, completed in 1900, contained twelve classrooms, a principal’s office, and an auditorium. Located on East University Avenue, it was later named in honor of Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith. Photograph from the postcard collection of Dr. Mark V. Barrow, Gainesville. The Historical Quarterly Volume LXVIII, Number April 1990 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY COPYRIGHT 1990 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. The Florida Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0015-4113) is published quarterly by the Florida Historical Society, Uni- versity of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620, and is printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, Florida. Second-class postage paid at Tampa and DeLeon Springs, Florida. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Florida Historical Society, P. O. Box 290197, Tampa, FL 33687. THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Samuel Proctor, Editor Everett W. Caudle, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL. ADVISORY BOARD David R. Colburn University of Florida Herbert J. Doherty University of Florida Michael V. Gannon University of Florida John K. Mahon University of Florida (Emeritus) Jerrell H. Shofner University of Central Florida Charlton W. Tebeau University of Miami (Emeritus) Correspondence concerning contributions, books for review, and all editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Florida Historical Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida 32604-2045. The Quarterly is interested in articles and documents pertaining to the history of Florida. Sources, style, footnote form, original- ity of material and interpretation, clarity of thought, and in- terest of readers are considered. All copy, including footnotes, should be double-spaced. Footnotes are to be numbered con- secutively in the text and assembled at the end of the article.