Militant South

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arkansas Department of Health 1913 – 2013

Old State House, original site of the Arkansas Department of Health 100 years of service Arkansas Department of Health 1913 – 2013 100yearsCover4.indd 1 1/11/2013 8:15:48 AM 100 YEARS OF SERVICE Current Arkansas Department of Health Location Booklet Writing/Editing Team: Ed Barham, Katheryn Hargis, Jan Horton, Maria Jones, Vicky Jones, Kerry Krell, Ann Russell, Dianne Woodruff, and Amanda Worrell The team of Department writers who compiled 100 Years of Service wishes to thank the many past and present employees who generously provided information, materials, and insight. Cover Photo: Reprinted with permission from the Old State House Museum. The Old State House was the original site of the permanent Arkansas State Board of Health in 1913. Arkansas Department of Health i 100 YEARS OF SERVICE Table of Contents A MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR ................................................................................................. 1 PREFACE ................................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................... 4 INFECTIOUS DISEASE .......................................................................................................................... 4 IMMUNIZATIONS ................................................................................................................................. 8 ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH -

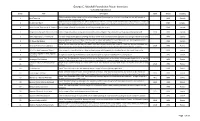

GCMF Poster Inventory

George C. Marshall Foundation Poster Inventory Compiled August 2011 ID No. Title Description Date Period Country A black and white image except for the yellow background. A standing man in a suit is reaching into his right pocket to 1 Back Them Up WWI Canada contribute to the Canadian war effort. A black and white image except for yellow background. There is a smiling soldier in the foreground pointing horizontally to 4 It's Men We Want WWI Canada the right. In the background there is a column of soldiers march in the direction indicated by the foreground soldier's arm. 6 Souscrivez à L'Emprunt de la "Victoire" A color image of a wide-eyed soldier in uniform pointing at the viewer. WWI Canada 2 Bring Him Home with the Victory Loan A color image of a soldier sitting with his gun in his arms and gear. The ocean and two ships are in the background. 1918 WWI Canada 3 Votre Argent plus 5 1/2 d'interet This color image shows gold coins falling into open hands from a Canadian bond against a blue background and red frame. WWI Canada A young blonde girl with a red bow in her hair with a concerned look on her face. Next to her are building blocks which 5 Oh Please Do! Daddy WWI Canada spell out "Buy me a Victory Bond" . There is a gray background against the color image. Poster Text: In memory of the Belgian soldiers who died for their country-The Union of France for Belgium and Allied and 7 Union de France Pour La Belqiue 1916 WWI France Friendly Countries- in the Church of St. -

The Mississippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History

Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists Volume 22 | Number 1 Article 5 January 2004 "The iM ssissippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History Lisa Speer Southeast Missouri State University Heather Mitchell State University of New York Albany Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/provenance Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Speer, Lisa and Mitchell, Heather, ""The iM ssissippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History," Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists 22 no. 1 (2004) . Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/provenance/vol22/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 51 "The Mississippi Plan": Dunbar Rowland and the Creation of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History Lisa Speer and Heather Mitchell · The establishment of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH) was a cultural milestone for a state that some regarded as backward in the latter decades of the twenti eth century. Alabama and Mississippi emerged as pioneers in the founding of state archives in 1901 and 1902 respectively, representing a growing awareness of the importance of pre serving historical records. American historians trained in Ger many had recently introduced the United States to the applica tion of scientific method to history. -

The Guidon 2016 - 2017

The Guidon 2016 - 2017 The South Carolina Corps of Cadets WELCOME TO THE CITADEL The Guidon is published every year as a source of information for fourth-class cadets. As a member of the Class of 2020, you are highly encouraged to familiarize yourself with all of the information enclosed in The Guidon. Since your initial time on campus will be filled with many activities, it is suggested to be familiar with as much of this information as possible before you report. The Guidon consists of two parts: general information that will help a cadet recruit become acclimated to The Citadel campus and lifestyle and required fourth-class knowledge, a mix of traditional Citadel knowledge and leader development knowledge. The cadet chain of command will test knobs on each piece of required knowledge and record the results in the tracking log in the back of The Guidon. This log and the process associated with it will be one assessment tool TACs can use as part of determining whether or not to certify cadets in several LDP learning outcomes. The required knowledge will be presented in manageable sizes that correspond to milestones in the fourth-classmen’s progression through the year. The milestones are broken down as follows: the end of Challenge Week, the end of Cadre Period, the end of first semester, and second semester until Recognition Day. The knowledge progresses from rudimentary information through more complex ideas, and culminates with the cadets becoming familiar with the Leadership Development Plan for The Citadel and how they will fit into that plan as upperclassmen. -

Rare Books, Autographs, Maps & Photographs

RARE BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHS, MAPS & PHOTOGRAPHS Wednesday, April 26, 2017 NEW YORK RARE BOOKS, AUTOGRAPHS, MAPS & PHOTOGRAPHS AUCTION Wednesday, April 26, 2017 at 10am EXHIBITION Saturday, April 22, 10am – 5pm Sunday, April 23, Noon – 5pm Monday, April 24, 10am – 5pm Tuesday, April 25, 10am – 2pm LOCATION Doyle New York 175 East 87th Street New York City 212-427-2730 www.Doyle.com Catalogue: $35 PHOTOGRAPHS CONTENTS Photographs Early Photography 1-14 20th Century Photography 15-122 Contemporary Photography 123-141 Rare Books, Autographs & Maps Printed & Manuscript Americana 142-197 Maps, Atlases & Travel Books 198-236 Property of the Estate of Donald Brenwasser 202-220 INCLUDING PROPERTY Plate Books 237-244 FROM THE ESTATES OF Donald Brenwasser Fine Bindings & Private Press 245-283 Roberta K. Cohn and Richard A. Cohn, Ltd Property of the Estate of Richard D. Friedlander 254-283 Richard D. Friedlander Mary Kettaneh Autographs 284-307 A New York and Connecticut Estate The Jessye Norman The Thurston Collection. ‘White Gates’ Collection 284-294 Manuscripts & Early printing 308-360 The College of New Rochelle INCLUDING PROPERTY FROM Collection of Thomas More 308-321 The Explorers Club Collection The College of New Rochelle Literature 361-414 A Prominent New York Family The College of New Rochelle The Jessye Norman ‘White Gates’ Collection Collection of James Joyce 361-381 A Private Collector, Ardsley, NY Pat Koch Thaler, sister of Edward Koch Applied Art & Livres d’Artistes 415-432 The Collection of Walter Ward, Jr The Watermill Center, Water Mill, New York Helen R. Yellin Conditions of Sale I Terms of Guarantee II Information on Sales & Use Tax III Buying at Doyle IV Selling at Doyle VI Auction Schedule VII Company Directory VIII Absentee Bid Form X Lot 24 5 [CIRCUS] Collection of 19th century cabinet cards and cartes des visites. -

Are You Arkansas-Literate?

Are you Arkansas-literate? 1.) Arkansas takes its name from which Indians: Autumn 2007 Quapaw, Caddo, Cherokee, Osage Volume 1 • Issue 1 2.) From Little Rock, which direction would one drive to reach Camden? 3.) the worst peacetime marine disaster, with 1,443 killed, involved which boat? Mound City, Sultana, Andrea Doria, Lusitania 4.) America’s first black municipal judge was: Scipio A. Jones, M. W. Gibbs, Wiley Branton, Marion Humphrey 5.) Which town is known as the Little Switzerland of America? Petit Jean, Magazine, Harrison, Eureka Springs Newsletter of the University of Arkansas Libraries Special Collections Department 6.) Sam Walton began his retail career with a “Five and Dime” in: Newport, Marianna, Jonesboro, Paragould 7.) the automobile made in Arkansas was the: Special Collections Celebrates Rebel Roadster, Hurricane, Cosmic, Climber COntentS 8.) the first state park in Arkansas was: 40th Anniversary: Please Join Us for Petit Jean, Mount Nebo, Lake Fort Smith, Moro Bay • Special Collections Celebrates 40th Workshops and Open House 9.) the Bowie Knife is believed to have been made at: Anniversary.........................1 Parkin, Hot Springs, Washington, Bigelow 10.) the Baltimore Orioles hall of famer from Little Rock was: • Leadership Report.............2 Special Collections will hold sev- Workshops on preserving family John G. Ragsdale, Preacher Roe, Brooks Robinson, Lon Warneke eral public events, including work- history records will be held on • Joan Watkins to Lead Index shops on preserving family history Saturday, October 20, 2007 at the Answers: 1.) Quapaw, 2.) South, 3.) Sultana, 4.) M. W. Gibbs, 5.) Eureka Springs, Arkansas Project................3 6.) Newport, 7.) Climber, 8.) Petit Jean, 9.) Washington, 10.) Brooks Robinson and oral history and an open house/ Fayetteville Public Library. -

Saber and Scroll Journal Volume VI Issue I Winter 2017 Saber And

Saber and Scroll Journal Volume VI Issue I Winter 2017 Saber and Scroll Historical Society 1 © Saber and Scroll Historical Society, 2018 Logo Design: Julian Maxwell Cover Design: Joan at the coronation of Charles VII, oil on canvas by Jean Auguest Dominique Ingres, c. 1854. Currently at Louvre Museum. Members of the Saber and Scroll Historical Society, the volunteer staff at the Saber and Scroll Journal publishes quarterly. saberandscroll.weebly.com 2 Journal Staff Editor in Chief Michael Majerczyk Copy Editors Anne Midgley, Michael Majerczyk Content Editors Tormod Engvig, Joe Cook, Mike Gottert, Kathleen Guler, Michael Majerczyk, Anne Midgley, Jack Morato, Chris Schloemer, Christopher Sheline Proofreaders Aida Dias, Tormod Engvig, Frank Hoeflinger, Anne Midgley, Michael Majerczyk, Jack Morato, John Persinger, Chris Schloemer, Susanne Watts Webmaster Jona Lunde Academic Advisors Emily Herff, Dr. Robert Smith, Jennifer Thompson 3 Contents Letter from the Editor 5 The Hundred Years War: A Different Contextual Overview Dr. Robert G. Smith 7 The Maiden of France: A Brief Overview of Joan of Arc and the Siege of Orléans 17 Cam Rea Joan of Arc through the Ages: In Art and Imagination 31 Anne Midgley Across the Etowah and into the Hell-Hole: Johnston’s Lost Chance for Victory in the Atlanta Campaign 47 Greg A. Drummond Cape Esperance: The Misunderstood Victory of Admiral Norman Scott 67 Jeffrey A. Ballard “Died on the Field of Honor, Sir.” Virginia Military Institute in the American Civil War and the Cadets Who Died at the Battle of New Market: May 15, 1864 93 Lew Taylor Exhibit and Book Reviews 105 4 Letter from the Editor Michael Majerczyk Hi everyone. -

The Florida Historical Quarterly

COVER The Gainesville Graded and High School, completed in 1900, contained twelve classrooms, a principal’s office, and an auditorium. Located on East University Avenue, it was later named in honor of Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith. Photograph from the postcard collection of Dr. Mark V. Barrow, Gainesville. The Historical Quarterly Volume LXVIII, Number April 1990 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY COPYRIGHT 1990 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. The Florida Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0015-4113) is published quarterly by the Florida Historical Society, Uni- versity of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620, and is printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, Florida. Second-class postage paid at Tampa and DeLeon Springs, Florida. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Florida Historical Society, P. O. Box 290197, Tampa, FL 33687. THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Samuel Proctor, Editor Everett W. Caudle, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL. ADVISORY BOARD David R. Colburn University of Florida Herbert J. Doherty University of Florida Michael V. Gannon University of Florida John K. Mahon University of Florida (Emeritus) Jerrell H. Shofner University of Central Florida Charlton W. Tebeau University of Miami (Emeritus) Correspondence concerning contributions, books for review, and all editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Florida Historical Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida 32604-2045. The Quarterly is interested in articles and documents pertaining to the history of Florida. Sources, style, footnote form, original- ity of material and interpretation, clarity of thought, and in- terest of readers are considered. All copy, including footnotes, should be double-spaced. Footnotes are to be numbered con- secutively in the text and assembled at the end of the article. -

Bridges & Dams

William Reese Company AMERICANA • RARE BOOKS • LITERATURE AMERICAN ART • PHOTOGRAPHY ______________________________ 409 TEMPLE STREET NEW HAVEN, CONNECTICUT 06511 (203) 789-8081 FAX (203) 865-7653 [email protected] Bridges & Dams How the West Was Built: A Mining and Electrical Engineer in Colorado and California 1. Armington, Howard C.: [PHOTOGRAPH ALBUM OF ENGINEER HOWARD C. ARMINGTON, DOCUMENTING HIS PARTICIPATION IN MASSIVE UTILITY PROJECTS IN COLORADO AND MINING EF- FORTS AND RAILROAD CONSTRUCTION IN CALIFORNIA IN THE EARLY 20th CENTURY]. [Various places in Colorado and California, as described below. ca. 1907-1913]. 406 photographs (395 silver prints, eleven cyanotypes) ranging in size from 2½ x 4 to 5 x 7 inches, one photo 9½ x 13 inches. All but six photos mounted in album. Oblong folio. Textured leather boards, secured by brads. Some chipping and wear to boards; minor fading and creasing to a few photos, but overall very well-preserved. Very good. A fascinating album documenting the early career of mining and civil engineer Howard C. Armington (1884-1966). The photographs in this album record several projects that Armington worked on early in his career, including electrification projects in Colorado, and mining, railroad, and dam construction in California. The photographs that Armington compiled in this extensive album provide out- standing evidence of projects that created an infrastructure allowing for increased migration westward, and increasing exploitation of western resources. The album begins with a photo of Armington as a student and member of the Crucible Club (precursor to the Beta Theta Pi fraternity) at the Colorado School of Mines (1906-07), there are then about 100 photographs highlighting his work with the Central Colorado Power Company (1908-09) building the Shoshone Hydroelectric Plant Complex. -

The Proceedings 2007

THE PROCEEDINGS of The South Carolina Historical Association 2007 Robert Figueira and Stephen Lowe Co-Editors The South Carolina Historical Association South Carolina Department of Archives and History Columbia, South Carolina www.palmettohistory.org/scha/scha.htm ii Officers of the Association President: Bernard Powers, College of Charleston Vice President: Joyce Wood, Anderson University Secretary: Ron Cox, University of South Carolina, Lancaster Treasurer: Rodger Stroup, South Carolina Department of Archives and History Executive and Editorial Board Members Andrew Myers, University of South Carolina, Upstate (7) E.E. “Wink” Prince, Jr., Coastal Carolina University (8) Tracy Power, South Carolina Department of Archives and History (9) Stephen Lowe, University of South Carolina Extended Graduate Campus, co-editor Robert C. Figueira, Lander University, co-editor The Proceedings of the South Carolina Historical Association 7 iii Officers of the Association Membership Application The SOUTH CAROLINA HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION is an organization that furthers the teaching and understanding of history. The only requirement for membership is an interest in and a love for history. At the annual meeting papers on European, Asian, U.S., Southern, and South Carolina history are routinely presented. Papers presented at the annual meeting may be published in The Proceedings, a refereed journal. Membership benefits include: a subscription toThe Proceedings of the South Carolina Historical Association, notification of the annual meeting, the right to submit a pro- posal for a paper for presentation at the annual meeting, the quarterly SCHA News- letter, and the annual membership roster of the Association. SCHA membership is from 1 January to 31 December. Student members must cur- rently be enrolled in school. -

Hotel Berlin

HOTEL BERLIN: THE POLITICS OF COMMERCIAL HOSPITALITY IN THE GERMAN METROPOLIS, 1875–1945 by Adam Bisno A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland December, 2017 © 2017 Adam Bisno ii Dissertation Advisor: Peter Jelavich Adam Bisno Hotel Berlin: The Politics of Commercial Hospitality in the German Metropolis, 1875–1945 Abstract This dissertation examines the institution of the grand hotel in Imperial, Weimar, and Nazi Berlin. It is a German cultural and business history of the fate of classical liberalism, which in practice treated human beings as rational, self-regulating subjects. The major shareholders in the corporations that owned the grand hotels, hotel managers, and hotel experts, through their daily efforts to keep the industry afloat amid the vicissitudes of modern German history, provide a vantage point from which to see the pathways from quotidian difficulties to political decisions, shedding light on how and why a multi-generational group of German businessmen embraced and then rejected liberal politics and culture in Germany. Treating the grand hotel as an institution and a space for the cultivation of liberal practices, the dissertation contributes to the recent body of work on liberal governance in the modern city by seeing the grand hotel as a field in which a dynamic, socially and culturally heterogeneous population tried and ultimately failed to determine the powers and parameters of liberal subjectivity. In locating the points at which liberal policies became impracticable, this dissertation also enters a conversation about the timing and causes of the crisis of German democracy. -

The Elaine Riot of 1919: Race, Class, and Labor in the Arkansas Delta" (2019)

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2019 The lE aine Riot of 1919: Race, Class, and Labor in the Arkansas Delta Steven Anthony University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Anthony, Steven, "The Elaine Riot of 1919: Race, Class, and Labor in the Arkansas Delta" (2019). Theses and Dissertations. 2040. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/2040 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ELAINE RIOT OF 1919: RACE, CLASS, AND LABOR IN THE ARKANSAS DELTA by Steven Anthony A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2019 ABSTRACT THE ELAINE RIOT OF 1919: RACE, CLASS, AND LABOR IN THE ARKANSAS DELTA by Steven Anthony The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2019 Under the Supervision of Professor Gregory Carter This dissertation examines the racially motivated mob dominated violence that took place during the autumn of 1919 in rural Phillips County, Arkansas nearby Elaine. The efforts of white planters to supplant the loss of enslaved labor due to the abolition of American slavery played a crucial role in re-making the southern agrarian economy in the early twentieth century. My research explores how the conspicuous features of sharecropping, tenant farming, peonage, or other variations of debt servitude became a means for the re-enslavement of African Americans in the Arkansas Delta.