The Florida Historical Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Everglades: Wetlands Not Wastelands Marjory Stoneman Douglas Overcoming the Barriers of Public Unawareness and the Profit Motive in South Florida

The Everglades: Wetlands not Wastelands Marjory Stoneman Douglas Overcoming the Barriers of Public Unawareness and the Profit Motive in South Florida Manav Bansal Senior Division Historical Paper Paper Length: 2,496 Bansal 1 "Marjory was the first voice to really wake a lot of us up to what we were doing to our quality of life. She was not just a pioneer of the environmental movement, she was a prophet, calling out to us to save the environment for our children and our grandchildren."1 - Florida Governor Lawton Chiles, 1991-1998 Introduction Marjory Stoneman Douglas was a vanguard in her ideas and approach to preserve the Florida Everglades. She not only convinced society that Florida’s wetlands were not wastelands, but also educated politicians that its value transcended profit. From the late 1800s, attempts were underway to drain large parts of the Everglades for economic gain.2 However, from the mid to late 20th century, Marjory Stoneman Douglas fought endlessly to bring widespread attention to the deteriorating Everglades and increase public awareness regarding its importance. To achieve this goal, Douglas broke societal, political, and economic barriers, all of which stemmed from the lack of familiarity with environmental conservation, apathy, and the near-sighted desire for immediate profit without consideration for the long-term impacts on Florida’s ecosystem. Using her voice as a catalyst for change, she fought to protect the Everglades from urban development and draining, two actions which would greatly impact the surrounding environment, wildlife, and ultimately help mitigate the effects of climate change. By educating the public and politicians, she served as a model for a new wave of environmental activism and she paved the way for the modern environmental movement. -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Today We Are Interviewing Mr

1 CENTER FOR FLORIDA HISTORY ORAL HISTORY PROGRAM INTERVIEW WITH: HOMER HOOKS INTERVIEWER: JAMES M. DENHAM PLACE: LAKELAND, FLORIDA DATE: JULY 29, 2003 M= JAMES M. DENHAM (Mike) H= HOMER HOOKS M: Today we are interviewing Mr. Homer Hooks and we are going to talk today about the legacy of Lawton Chiles and hopefully follow this up with future discussions of Mr. Hooks’ business career and career in politics. Good morning Mr. Hooks. H: Good morning, Mike. M: As I mentioned, we, really, in the future want to talk about your service in World War II and also your business career, but today we would like to focus on your memories of Lawton Chiles. Even so, can you tell us a little bit about where you were born as well as giving us a brief biographical sketch? H: Yes, Mike. I was born in Columbia, South Carolina, on January 10, 1921. My family moved to Lake County actually in Florida when I was a child. I was 4 or 5 years old, I guess. We lived in Clermont in south Lake County. My grandfather was a pioneer. He platted the town of Clermont. The rest of the family also lived north of Clermont in the Leesburg area, but we considered ourselves pioneer Florida residents. Those were the days in 1926, ‘27 and ‘28 days and so forth. I grew up in Clermont - grammar school and high school and then immediately went to the University of Florida in 1939 and graduated in 1943, as some people have said, when the earth’s crust was still cooling, so long ago. -

Doggin' America's Beaches

Doggin’ America’s Beaches A Traveler’s Guide To Dog-Friendly Beaches - (and those that aren’t) Doug Gelbert illustrations by Andrew Chesworth Cruden Bay Books There is always something for an active dog to look forward to at the beach... DOGGIN’ AMERICA’S BEACHES Copyright 2007 by Cruden Bay Books All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the Publisher. Cruden Bay Books PO Box 467 Montchanin, DE 19710 www.hikewithyourdog.com International Standard Book Number 978-0-9797074-4-5 “Dogs are our link to paradise...to sit with a dog on a hillside on a glorious afternoon is to be back in Eden, where doing nothing was not boring - it was peace.” - Milan Kundera Ahead On The Trail Your Dog On The Atlantic Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Gulf Of Mexico Beaches 6 Your Dog On The Pacific Ocean Beaches 7 Your Dog On The Great Lakes Beaches 0 Also... Tips For Taking Your Dog To The Beach 6 Doggin’ The Chesapeake Bay 4 Introduction It is hard to imagine any place a dog is happier than at a beach. Whether running around on the sand, jumping in the water or just lying in the sun, every dog deserves a day at the beach. But all too often dog owners stopping at a sandy stretch of beach are met with signs designed to make hearts - human and canine alike - droop: NO DOGS ON BEACH. -

Florida Expressways and the Public Works Career of Congressman William C

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-8-2008 Florida Expressways and the Public Works Career of Congressman William C. Cramer Justin C. Whitney University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Whitney, Justin C., "Florida Expressways and the Public Works Career of Congressman William C. Cramer" (2008). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/563 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Florida Expressways and the Public Works Career of Congressman William C. Cramer by Justin C. Whitney A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of American Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Gary R. Mormino, Ph.D. Raymond O. Arsenault, Ph.D. Darryl G. Paulson, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 8, 2008 Keywords: interstate highway, turnpike, politics, St. Petersburg, Tampa Bay © Copyright 2008, Justin C. Whitney Table of Contents Abstract ii Introduction 1 The First Wave 6 The Gridlock City 12 Terrific Amount of Rock 17 Interlopers 26 Bobtail 38 Clash 54 Fruitcake 67 Posies 82 Umbrella 93 The Missing Link 103 Mickey Mouse Road 114 Southern Strategy 123 Breaking New Ground 128 Yes We Can 132 Notes 141 Bibliography 173 i Florida Expressways and the Public Works Career of Congressman William C. -

Investigating Second Seminole War Sites in Florida: Identification Through Limited Testing Christine Bell University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-19-2004 Investigating Second Seminole War Sites in Florida: Identification Through Limited Testing Christine Bell University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Bell, Christine, "Investigating Second Seminole War Sites in Florida: Identification Through Limited Testing" (2004). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/952 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Investigating Second Seminole War Sites in Florida: Identification Through Limited Testing by Christine Bell A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Brent R. Weisman, Ph.D. Robert H. Tykot, Ph.D. E. Christian Wells, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 19, 2004 Keywords: Historical archaeology, artifact dating, military forts, correspondence analysis, homesteads © Copyright 2004, Christine Bell i Acknowledgements None of this work would be possible without the support of family, friends, and the wonderful volunteers who helped at our sites. Thank you to Debbie Roberson, Lori Collins, and my committee members Dr. Weisman, Dr. Wells, and Dr. Tykot. I couldn’t have made it through grad school without Toni, and Belle, and even Mel. A special thanks to Walter for inspiring me from the start. -

Fort King National Historic Landmark Education Guide 1 Fig5

Ai-'; ~,,111m11l111nO FORTKINO NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK Fig1 EDUCATION GUIDE This guide was made possible by the City of Ocala Florida and the Florida Department of State/Division of Historic Resources WELCOME TO Micanopy WE ARE EXCITED THAT YOU HAVE CHOSEN Fort King National Historic Fig2 Landmark as an education destination to shed light on the importance of this site and its place within the Seminole War. This Education Guide will give you some tools to further educate before and after your visit to the park. The guide gives an overview of the history associated with Fort King, provides comprehension questions, and delivers activities to Gen. Thomas Jesup incorporate into the classroom. We hope that this resource will further Fig3 enrich your educational experience. To make your experience more enjoyable we have included a list of items: • Check in with our Park Staff prior to your scheduled visit to confrm your arrival time and participation numbers. • The experience at Fort King includes outside activities. Please remember the following: » Prior to coming make staff aware of any mobility issues or special needs that your group may have. » Be prepared for the elements. Sunscreen, rain gear, insect repellent and water are recommended. » Wear appropriate footwear. Flip fops or open toed shoes are not recommended. » Please bring lunch or snacks if you would like to picnic at the park before or after your visit. • Be respectful of our park staff, volunteers, and other visitors by being on time. Abraham • Visitors will be exposed to different cultures and subject matter Fig4 that may be diffcult at times. -

Seminole Wars Heritage Trail

Central Gulf Coast Archaeological Society 41 YEARS OF PROMOTING FLORIDA’S RICH HERITAGE CGCAS IS A CHAPTER OF THE FLORIDA ANTHROPOLOGICAL SOCIETY Newsletter | OCTOBER 2019 | Thursday, October 17th, 7pm Adventures in Downtown Tampa Archaeology- The Lost Fort Brooke Cemetery and 100-Year-Old Love Letters to the Steamer Gopher Eric Prendergast, MA RPA, Senior Staff Archaeologist, Cardno Almost everywhere you dig in southern downtown Tampa, near the water front, there are some remains from the infamous military installation that gave rise to the town of Tampa in the early 1800s. It has long been known that Fort Brooke had two cemeteries, but only one of them was ever found and excavated in the 1980s. Recent excavations across downtown Tampa have focused on the hunt for the second lost cemetery, among many other components of the fort. While testing the model designed to locate the cemetery, a sealed jar was discovered, crammed full of letters written in 1916. The letters were mailed to someone aboard C. B. Moore’s steamer Gopher, while the ship completed it’s 1916 expedition on the Mississippi River. What were they doing buried in a parking lot in Tampa? Eric is a transplant from the northeast who has only lived in Tampa since 2012, when he came to graduate school at USF. Since then he has worked in CRM and has recently served as Principal Investigator for major excavations in Downtown Tampa and for the Zion Cemetery Project, Robles Park Village. The monthly CGCAS Archaeology Lecture series is sponsored by the Alliance for Weedon Island Archaeological Research and Education (AWIARE) and held at the Weedon Island Preserve Cultural and Natural History Center in St Petersburg. -

GCMF Poster Inventory

George C. Marshall Foundation Poster Inventory Compiled August 2011 ID No. Title Description Date Period Country A black and white image except for the yellow background. A standing man in a suit is reaching into his right pocket to 1 Back Them Up WWI Canada contribute to the Canadian war effort. A black and white image except for yellow background. There is a smiling soldier in the foreground pointing horizontally to 4 It's Men We Want WWI Canada the right. In the background there is a column of soldiers march in the direction indicated by the foreground soldier's arm. 6 Souscrivez à L'Emprunt de la "Victoire" A color image of a wide-eyed soldier in uniform pointing at the viewer. WWI Canada 2 Bring Him Home with the Victory Loan A color image of a soldier sitting with his gun in his arms and gear. The ocean and two ships are in the background. 1918 WWI Canada 3 Votre Argent plus 5 1/2 d'interet This color image shows gold coins falling into open hands from a Canadian bond against a blue background and red frame. WWI Canada A young blonde girl with a red bow in her hair with a concerned look on her face. Next to her are building blocks which 5 Oh Please Do! Daddy WWI Canada spell out "Buy me a Victory Bond" . There is a gray background against the color image. Poster Text: In memory of the Belgian soldiers who died for their country-The Union of France for Belgium and Allied and 7 Union de France Pour La Belqiue 1916 WWI France Friendly Countries- in the Church of St. -

June 1-15, 1972

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/2/1972 A Appendix “B” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/5/1972 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/6/1972 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/9/1972 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/12/1972 A Appendix “B” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-10 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary June 1, 1972 – June 15, 1972 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) THF WHITE ,'OUSE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON'S DAILY DIARY (Sec Travel Record for Travel AnivilY) f PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day. Yr.) _u.p.-1:N_E I, 1972 WILANOW PALACE TIME DAY WARSAW, POLi\ND 7;28 a.m. THURSDAY PHONE TIME P=Pl.ccd R=Received ACTIVITY 1----.,------ ----,----j In Out 1.0 to 7:28 P The President requested that his Personal Physician, Dr. -

Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4

Florida Historical Quarterly Volume 63 Number 4 Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume Article 1 63, Number 4 1984 Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4 Florida Historical Society [email protected] Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Historical Quarterly by an authorized editor of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Society, Florida Historical (1984) "Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4," Florida Historical Quarterly: Vol. 63 : No. 4 , Article 1. Available at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol63/iss4/1 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4 Published by STARS, 1984 1 Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 63 [1984], No. 4, Art. 1 COVER Opening joint session of the Florida legislature in 1953. It is traditional for flowers to be sent to legislators on this occasion, and for wives to be seated on the floor. Florida’s cabinet is seated just below the speaker’s dais. Secretary of State Robert A. Gray is presiding for ailing Governor Dan T. McCarty. Photograph courtesy of the Florida State Archives. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/fhq/vol63/iss4/1 2 Society: Florida Historical Quarterly, Volume 63, Number 4 Volume LXIII, Number 4 April 1985 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY COPYRIGHT 1985 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. Second class postage paid at Tampa and DeLeon Springs, Florida. Printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, Florida. -

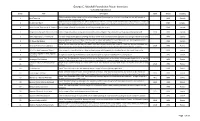

Proposed Congressional District 1 (Plan S00C0002)

Proposed Congressional District 1 (Plan S00C0002) Total District Population 639,295 General Election 2000 Deviation 0 0.0% President of the United States Bush, George W. & Dick Cheney (REP) 178,133 67.7% Total Population (2000 Census) 639,295 100.0% Gore, Al & Joe Lieberman (DEM) 78,332 29.8% Single-Race Non-Hispanic White 501,260 78.4% Nader, Ralph & Winona LaDuke (GRE) 3,783 1.4% Non-Hispanic Black (including multirace) 89,756 14.0% All Other Candidates 2,703 1.0% Hispanic Black (including multirace) 1,338 0.2% United States Senator Hispanic (excluding Hisp Black) 18,070 2.8% McCollum, Bill (REP) 163,707 64.8% Non-Hispanic Other (none of the above) 28,871 4.5% Nelson, Bill (DEM) 88,815 35.2% Male 320,806 50.2% Treasurer and Ins. Comm. Female 318,489 49.8% Gallagher, Tom (REP) 184,114 72.9% Age 17 and younger 155,069 24.3% Cosgrove, John (DEM) 68,360 27.1% Age 18 to 64 402,580 63.0% Commissioner of Education Age 65 and older 81,646 12.8% Crist, Charlie (REP) 164,435 67.5% Sheldon, George H. (DEM) 79,313 32.5% Voting Age Population (2000 Census) 484,226 100.0% Democratic Primary 2000 Single-Race Non-Hispanic White 389,850 80.5% Commissioner of Education Non-Hispanic Black (including multirace) 59,845 12.4% Bush III, James (DEM) 16,130 34.8% Hispanic Black (including multirace) 773 0.2% Sheldon, George H. (DEM) 30,269 65.2% Hispanic (excluding Hisp Black) 12,714 2.6% General Election 1998 Non-Hispanic Other (none of the above) 21,044 4.3% United States Senator Crist, Charlie (REP) 87,047 51.8% Population Change (2000-1990) 109,679 20.7%