Hotel Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC SCULPTURE LOCATIONS Introduction to the PHOTOGRAPHY: 17 Daniel Portnoy PUBLIC Public Sculpture Collection Sid Hoeltzell SCULPTURE 18

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VIRGINIO FERRARI RAFAEL CONSUEGRA UNKNOWN ARTIST DALE CHIHULY THERMAN STATOM WILLIAM DICKEY KING JEAN CLAUDE RIGAUD b. 1937, Verona, Italy b. 1941, Havana, Cuba Bust of José Martí, not dated b. 1941, Tacoma, Washington b. 1953, United States b. 1925, Jacksonville, Florida b. 1945, Haiti Lives and works in Chicago, Illinois Lives and works in Miami, Florida bronze Persian and Horn Chandelier, 2005 Creation Ladder, 1992 Lives and works in East Hampton, New York Lives and works in Miami, Florida Unity, not dated Quito, not dated Collection of the University of Miami glass glass on metal base Up There, ca. 1971 Composition in Circumference, ca. 1981 bronze steel and paint Location: Casa Bacardi Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Carol and Richard S. Fine aluminum steel and paint Collection of the University of Miami Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Camner Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center University of Miami University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Blake King, 2004.20 Gift of Dr. Maurice Rich, 2003.14 Location: Wellness Center Location: Pentland Tower 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 JANE WASHBURN LEONARDO NIERMAN RALPH HURST LEONARDO NIERMAN LEOPOLDO RICHTER LINDA HOWARD JOEL PERLMAN b. United States b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1918, Decatur, Indiana b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1896, Großauheim, Germany b. 1934, Evanston, Illinois b. -

Officieele Gids Voor De Olympische Spelen Ter Viering Van De Ixe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928

Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 samenstelling Nederlands Olympisch Comité bron Nederlands Olympisch Comité (samenstelling), Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928. Holdert & Co. en A. de la Mar Azn., z.p. z.j. [Amsterdam ca. 1928] Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_ned016offi01_01/colofon.htm © 2009 dbnl 1 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 2 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 3 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 4 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 5 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 6 [advertentie] Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 7 Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade Amsterdam 1928 UITGEGEVEN MET MEDEWERKING VAN HET COMITÉ 1928 (NED. OLYMPISCH COMITÉ) UITGAVE HOLDERT & Co. en A. DE LA MAR Azn. Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 8 Mr. A. Baron Schimmelpenninck van der Oye Voorzitter der Olympische Spelen 1928 Président du Comité Exécutif 1928 Vorsitzender des Vollzugsausschusses 1928 President of the Executive Committee 1928 Officieele gids voor de Olympische Spelen ter viering van de IXe Olympiade, Amsterdam 1928 9 Voorwoord. Een kort woord ter aanbeveling van den officieelen Gids. -

Cinema-Going at the Antwerp Zoo (1915–1936): a Cinema-Concert Program Database Arts and Media

research data journal for the humanities and social sciences 5 (2020) 41-49 brill.com/rdj Cinema-going at the Antwerp Zoo (1915–1936): A Cinema-concert Program Database Arts and Media Leen Engelen LUCA School of Arts / KU Leuven, Genk, Belgium [email protected] Thomas Crombez Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp, Belgium [email protected] Roel Vande Winkel KU Leuven / LUCA School of Arts, Louvain, Belgium [email protected] Abstract This paper outlines the genesis of the cinema-concert program database of the Belgian movie theatre Cinema Zoologie (1915–1936) deposited in the dans repository. First, it provides a detailed account of the historical sources and the data collection process. Second, it explains the structure of the database and the coding that was used to enter the data. Finally, the strengths and weaknesses of the database are discussed and its potential for future research is highlighted. Keywords cinema-going – cinema culture – film – concert – Belgium – First World War – film programs – classical music © ENGELEN ET AL., 2020 | doi:10.1163/24523666-bja10013 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the cc-by 4.0Downloaded license. from Brill.com09/26/2021 06:17:23PM via free access <UN> 42 Engelen, Crombez and VANDE Winkel – Related data set “Cinema Zoologie 1915–1936: A film programming database” with doi https://www.doi.org/10.17026/dans-x4q-jv9z in repository “dans” – See the showcase of the data in the Exhibit of Datasets: https://www.dans datajournal.nl/rdp/exhibit.html?showcase=engelen2020 1. Introduction This paper outlines the genesis, data and structure of a cinema-concert pro- gram database of the Belgian movie theatre Cinema Zoologie (1915–1936) de- posited in the dans repository. -

Chryssa B. 1933, Athens D. 2013, Athens New York Times 1975–78

Chryssa b. 1933, Athens d. 2013, Athens New York Times 1975–78 Oil and graphite on canvas Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Michael Bennett 80.2717 Chryssa began making stamped paintings based on the New York Times in 1958 and continued to do so into the 1970s. To create these works, she had rubber stamps produced based on portions of the newspaper before, as she described it, covering “the entire area [of a canvas] with a fragment repeated precisely.” Over time Chryssa’s treatment of the motif became increasingly abstract, as she more strictly adhered to a gridded composition and selected sections of newsprint with type too small to be legibly rendered in rubber. By deemphasizing the content and format of the newspaper, she redirected focus to the tension between mechanized reproduction and her careful process of stamping by hand. Jacob El Hanani b. 1947, Casablanca Untitled #171 1976–77 Ink and acrylic on canvas Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Mr. and Mrs. George M. Jaffin 77.2291 With its dense profusion of finely drawn lines, Jacob El Hanani’s Untitled #171 is a feat of physical endurance, patience, and precision. As the artist said, “It is a personal challenge to bring drawing to the extreme and see how far my eyes and fingers can go.” Rather than approach this effort as an end unto itself, El Hanani has often related it to Jewish traditions of handwriting religious texts—a parallel suggesting a desire to transcend the self through a devotional level of discipline. This aspiration is given form in the way the short, variously weighted lines lose their discreteness from afar and blend into a vaporous whole. -

John Taitano June 19, 2018 6:49 Am CT

NWX-FWS (US) Moderator: John Taitano 06-19-18/4:00 pm CT Confirmation # 932358 Page 1 NWX-FWS (US) Moderator: John Taitano June 19, 2018 6:49 am CT Coordinator: Thank you for standing by. I'd like to inform all parties that today's conference is being recorded. If you have any objections you may disconnect at this time. For assistance during your conference, please press Star 0. Thank you. You may begin. ((Crosstalk)) Bill Brewster: Okay, good to have everybody here for our second meeting of IWCC. Glad everyone took the time to come in and share their thoughts. We have some presenters that I think can be quite helpful. Our main job is to learn and educate ourselves as much as possible on all aspects of wildlife, wildlife management, sustainable wildlife management. And what I would like to do is first go around the room and let each council member introduce themselves, tell where they're from, and then we'll go from there. Why don't we start with (Keith Martin)? (Keith Martin): (Keith Martin) I'm from Camdenton, and I was (unintelligible). NWX-FWS (US) Moderator: John Taitano 06-19-18/4:00 pm CT Confirmation # 932358 Page 2 Erica Rhoad: I’m Erica Rhoad, National Rifle Association (unintelligible). Man 1: Could we have - make sure that you push that button in front of you? Could we start again with (Keith)? Push that button and when you're done if you'd turn it off so that it doesn't get a lot of feedback. -

Berlin - Wikipedia

Berlin - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin Coordinates: 52°30′26″N 13°8′45″E Berlin From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Berlin (/bɜːrˈlɪn, ˌbɜːr-/, German: [bɛɐ̯ˈliːn]) is the capital and the largest city of Germany as well as one of its 16 Berlin constituent states, Berlin-Brandenburg. With a State of Germany population of approximately 3.7 million,[4] Berlin is the most populous city proper in the European Union and the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Located in northeastern Germany on the banks of the rivers Spree and Havel, it is the centre of the Berlin- Brandenburg Metropolitan Region, which has roughly 6 million residents from more than 180 nations[6][7][8][9], making it the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Due to its location in the European Plain, Berlin is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. Around one- third of the city's area is composed of forests, parks, gardens, rivers, canals and lakes.[10] First documented in the 13th century and situated at the crossing of two important historic trade routes,[11] Berlin became the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg (1417–1701), the Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918), the German Empire (1871–1918), the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and the Third Reich (1933–1945).[12] Berlin in the 1920s was the third largest municipality in the world.[13] After World War II and its subsequent occupation by the victorious countries, the city was divided; East Berlin was declared capital of East Germany, while West Berlin became a de facto West German exclave, surrounded by the Berlin Wall [14] (1961–1989) and East German territory. -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

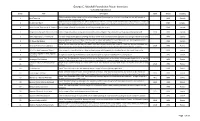

GCMF Poster Inventory

George C. Marshall Foundation Poster Inventory Compiled August 2011 ID No. Title Description Date Period Country A black and white image except for the yellow background. A standing man in a suit is reaching into his right pocket to 1 Back Them Up WWI Canada contribute to the Canadian war effort. A black and white image except for yellow background. There is a smiling soldier in the foreground pointing horizontally to 4 It's Men We Want WWI Canada the right. In the background there is a column of soldiers march in the direction indicated by the foreground soldier's arm. 6 Souscrivez à L'Emprunt de la "Victoire" A color image of a wide-eyed soldier in uniform pointing at the viewer. WWI Canada 2 Bring Him Home with the Victory Loan A color image of a soldier sitting with his gun in his arms and gear. The ocean and two ships are in the background. 1918 WWI Canada 3 Votre Argent plus 5 1/2 d'interet This color image shows gold coins falling into open hands from a Canadian bond against a blue background and red frame. WWI Canada A young blonde girl with a red bow in her hair with a concerned look on her face. Next to her are building blocks which 5 Oh Please Do! Daddy WWI Canada spell out "Buy me a Victory Bond" . There is a gray background against the color image. Poster Text: In memory of the Belgian soldiers who died for their country-The Union of France for Belgium and Allied and 7 Union de France Pour La Belqiue 1916 WWI France Friendly Countries- in the Church of St. -

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History

Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe New Perspectives on Modern Jewish History Edited by Cornelia Wilhelm Volume 8 Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe Shared and Comparative Histories Edited by Tobias Grill An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-048937-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049248-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-048977-4 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Grill, Tobias. Title: Jews and Germans in Eastern Europe : shared and comparative histories / edited by/herausgegeben von Tobias Grill. Description: [Berlin] : De Gruyter, [2018] | Series: New perspectives on modern Jewish history ; Band/Volume 8 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018019752 (print) | LCCN 2018019939 (ebook) | ISBN 9783110492484 (electronic Portable Document Format (pdf)) | ISBN 9783110489378 (hardback) | ISBN 9783110489774 (e-book epub) | ISBN 9783110492484 (e-book pdf) Subjects: LCSH: Jews--Europe, Eastern--History. | Germans--Europe, Eastern--History. | Yiddish language--Europe, Eastern--History. | Europe, Eastern--Ethnic relations. | BISAC: HISTORY / Jewish. | HISTORY / Europe / Eastern. Classification: LCC DS135.E82 (ebook) | LCC DS135.E82 J495 2018 (print) | DDC 947/.000431--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019752 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

Wagenreihungen Der Deutschen Bahn Erstellt: Marcus Grahnert

Wagenreihungen der Deutschen Bahn erstellt: Marcus Grahnert www.fernbahn.de Jahresfahrplan 2021 # Zugnummern 2 - 99 Zug Startbahnhof Zielbahnhof Vmax Fahrtrichtung ICE 3 Karlsruhe Hbf Zürich HB 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 9 10 11 12 14 250 km/h < Karlsruhe Hbf - Basel SBB Basel SBB - Zürich HB > Bpmdzf Bpmz Bpmz Bpmz Bpmz BpmzBpmz Bpmbsz ARmz Apmz Apmz Apmzf ICE 4 Kleinkindabteil 9 Abteil für Behinderte 1, 9, 10, 14 rollstuhlgerecht 9 Fahrrad 1 Reihung gültig Mo-Fr ICE 3 Basel SBB Zürich HB 14 12 11 10 9 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 < Basel SBB - Zürich HB Apmzf Apmz Apmz ARmz BpmbszBpmz Bpmz Bpmz Bpmz Bpmz Bpmz Bpmdzf ICE 4 Kleinkindabteil 9 Abteil für Behinderte 1, 9, 10, 14 rollstuhlgerecht 9 Fahrrad 1 Reihung gültig Sa und So ICE 4 Zürich HB Frankfurt(M)Hbf 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 9 10 11 12 14 250 km/h < Zürich HB - Basel SBB Basel SBB - Frankfurt(M)Hbf > Bpmdzf Bpmz BpmzBpmz Bpmz Bpmz Bpmz Bpmbsz ARmz Apmz Apmz Apmzf ICE 4 Kleinkindabteil9 Abteil für Behinderte 1, 9, 10, 14 rollstuhlgerecht 9 Fahrrad 1 ICE 5 Frankfurt(M)Hbf Basel SBB 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 9 10 11 12 14 250 km/h < Frankfurt(M)Hbf - Basel SBB BpmdzfBpmz BpmzBpmz Bpmz Bpmz Bpmz Bpmbsz ARmz Apmz Apmz Apmzf ICE 4 Kleinkindabteil 9 Abteil für Behinderte 1, 9, 10, 14 rollstuhlgerecht 9 Fahrrad 1 Reihung gültig Mo-Fr ICE 5 Frankfurt(M)Hbf Basel SBB 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 14 280 km/h < Frankfurt(M)Hbf - Basel SBB Bvmz BvmzBvmz Bvmz Bvmz Bpmz Bvmz WRmz ApmbszAvmz Avmz Avmz ICE 1 Kleinkindabteil 9 Abteil für Behinderte 7, 9 rollstuhlgerecht 9 Fahrrad --- Reihung gültig Sa Kurzanleitung: 1. -

The Ashgate Research Companion to Imperial Germany ASHGATE RESEARCH COMPANION

ASHGATE RESEARCH COMPANION THE ASHGatE RESEarCH COMPANION TO IMPERIAL GERMANY ASHGATE RESEARCH COMPANION The Ashgate Research Companions are designed to offer scholars and graduate students a comprehensive and authoritative state-of-the-art review of current research in a particular area. The companions’ editors bring together a team of respected and experienced experts to write chapters on the key issues in their speciality, providing a comprehensive reference to the field. The Ashgate Research Companion to Imperial Germany Edited by MattHEW JEFFERIES University of Manchester, UK © Matthew Jefferies 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Matthew Jefferies has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the editor of this work. Published by Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East 110 Cherry Street Union Road Suite 3-1 Farnham Burlington, VT 05401-3818 Surrey, GU9 7PT USA England www.ashgate.com British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Ashgate research companion to Imperial Germany / edited by Matthew Jefferies. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4094-3551-8 (hardcover) – ISBN 978-1-4094-3552-5 -

The Marshall Plan in Austria 69

CAS XXV CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIANAUSTRIAN STUDIES STUDIES | VOLUME VOLUME 25 25 This volume celebrates the study of Austria in the twentieth century by historians, political scientists and social scientists produced in the previous twenty-four volumes of Contemporary Austrian Studies. One contributor from each of the previous volumes has been asked to update the state of scholarship in the field addressed in the respective volume. The title “Austrian Studies Today,” then, attempts to reflect the state of the art of historical and social science related Bischof, Karlhofer (Eds.) • Austrian Studies Today studies of Austria over the past century, without claiming to be comprehensive. The volume thus covers many important themes of Austrian contemporary history and politics since the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy in 1918—from World War I and its legacies, to the rise of authoritarian regimes in the 1930s and 1940s, to the reconstruction of republican Austria after World War II, the years of Grand Coalition governments and the Kreisky era, all the way to Austria joining the European Union in 1995 and its impact on Austria’s international status and domestic politics. EUROPE USA Austrian Studies Studies Today Today GünterGünter Bischof,Bischof, Ferdinand Ferdinand Karlhofer Karlhofer (Eds.) (Eds.) UNO UNO PRESS innsbruck university press UNO PRESS UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Austrian Studies Today Günter Bischof, Ferdinand Karlhofer (Eds.) CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | VOLUME 25 UNO PRESS innsbruck university press Copyright © 2016 by University of New Orleans Press All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage nd retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.