Polo-Like Kinases in the Nervous System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Supplemental Information to Mammadova-Bach Et Al., “Laminin Α1 Orchestrates VEGFA Functions in the Ecosystem of Colorectal Carcinogenesis”

Supplemental information to Mammadova-Bach et al., “Laminin α1 orchestrates VEGFA functions in the ecosystem of colorectal carcinogenesis” Supplemental material and methods Cloning of the villin-LMα1 vector The plasmid pBS-villin-promoter containing the 3.5 Kb of the murine villin promoter, the first non coding exon, 5.5 kb of the first intron and 15 nucleotides of the second villin exon, was generated by S. Robine (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The EcoRI site in the multi cloning site was destroyed by fill in ligation with T4 polymerase according to the manufacturer`s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France). Site directed mutagenesis (GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis system, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) was then used to introduce a BsiWI site before the start codon of the villin coding sequence using the 5’ phosphorylated primer: 5’CCTTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGCGTACGATGACGTCGGACTTGCGG3’. A double strand annealed oligonucleotide, 5’GGCCGGACGCGTGAATTCGTCGACGC3’ and 5’GGCCGCGTCGACGAATTCACGC GTCC3’ containing restriction site for MluI, EcoRI and SalI were inserted in the NotI site (present in the multi cloning site), generating the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. The SV40 polyA region of the pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France) was amplified by PCR using primers 5’GGCGCCTCTAGATCATAATCAGCCATA3’ and 5’GGCGCCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTT3’ before subcloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France). After EcoRI digestion, the SV40 polyA fragment was purified with the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a BsiWI site (5’ phosphorylated AGCGCAGGGAGCGGCGGCCGTACGATGCGCGGCAGCGGCACG3’) before the initiation codon and a MluI site (5’ phosphorylated 1 CCCGGGCCTGAGCCCTAAACGCGTGCCAGCCTCTGCCCTTGG3’) after the stop codon in the full length cDNA coding for the mouse LMα1 in the pCIS vector (kindly provided by P. -

Polo-Like Kinases Mediate Cell Survival in Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Polo-like kinases mediate cell survival in mitochondrial dysfunction Takumi Matsumotoa,1, Ping-yuan Wanga,1, Wenzhe Maa, Ho Joong Sunga, Satoaki Matobab, and Paul M. Hwanga,2 aTranslational Medicine Branch, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892; and bCardiovascular Medicine, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Kyoto 602-8566, Japan Edited by Solomon H. Snyder, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, and approved July 10, 2009 (received for review April 16, 2009) Cancer cells often display defects in mitochondrial respiration, thus significant respiration (Fig. S1). For the described in vitro the identification of pathways that promote cell survival under this experiments, one representative SCO2-/- cell line was used. metabolic state may have therapeutic implications. Here, we report However, all significant findings were reproduced or confirmed that the targeted ablation of mitochondrial respiration markedly using at least one additional SCO2-/- cell line that was obtained increases expression of Polo-like kinase 2 (PLK2) and that it is by an independent homologous recombination event to rule out required for the in vitro growth of these nonrespiring cells. clonal variability. Furthermore, we identify PLK2 as a kinase that phosphorylates In an attempt to identify genes associated with the cell cycle Ser-137 of PLK1, which is sufficient to mediate this survival signal. that may enable the survival of SCO2-/- cells after disruption of In vivo, knockdown of PLK2 in an isogenic human cell line with a respiration, we compared microarray gene expression of respir- modest defect in mitochondrial respiration eliminates xenograft ing SCO2ϩ/ϩ and nonrespiring SCO2-/- HCT116 human colon formation, indicating that PLK2 activity is necessary for growth of cancer cells (Table S1). -

Application of a MYC Degradation

SCIENCE SIGNALING | RESEARCH ARTICLE CANCER Copyright © 2019 The Authors, some rights reserved; Application of a MYC degradation screen identifies exclusive licensee American Association sensitivity to CDK9 inhibitors in KRAS-mutant for the Advancement of Science. No claim pancreatic cancer to original U.S. Devon R. Blake1, Angelina V. Vaseva2, Richard G. Hodge2, McKenzie P. Kline3, Thomas S. K. Gilbert1,4, Government Works Vikas Tyagi5, Daowei Huang5, Gabrielle C. Whiten5, Jacob E. Larson5, Xiaodong Wang2,5, Kenneth H. Pearce5, Laura E. Herring1,4, Lee M. Graves1,2,4, Stephen V. Frye2,5, Michael J. Emanuele1,2, Adrienne D. Cox1,2,6, Channing J. Der1,2* Stabilization of the MYC oncoprotein by KRAS signaling critically promotes the growth of pancreatic ductal adeno- carcinoma (PDAC). Thus, understanding how MYC protein stability is regulated may lead to effective therapies. Here, we used a previously developed, flow cytometry–based assay that screened a library of >800 protein kinase inhibitors and identified compounds that promoted either the stability or degradation of MYC in a KRAS-mutant PDAC cell line. We validated compounds that stabilized or destabilized MYC and then focused on one compound, Downloaded from UNC10112785, that induced the substantial loss of MYC protein in both two-dimensional (2D) and 3D cell cultures. We determined that this compound is a potent CDK9 inhibitor with a previously uncharacterized scaffold, caused MYC loss through both transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms, and suppresses PDAC anchorage- dependent and anchorage-independent growth. We discovered that CDK9 enhanced MYC protein stability 62 through a previously unknown, KRAS-independent mechanism involving direct phosphorylation of MYC at Ser . -

Mithramycin Represses Basal and Cigarette Smoke–Induced Expression of ABCG2 and Inhibits Stem Cell Signaling in Lung and Esophageal Cancer Cells

Cancer Therapeutics, Targets, and Chemical Biology Research Mithramycin Represses Basal and Cigarette Smoke–Induced Expression of ABCG2 and Inhibits Stem Cell Signaling in Lung and Esophageal Cancer Cells Mary Zhang1, Aarti Mathur1, Yuwei Zhang1, Sichuan Xi1, Scott Atay1, Julie A. Hong1, Nicole Datrice1, Trevor Upham1, Clinton D. Kemp1, R. Taylor Ripley1, Gordon Wiegand2, Itzak Avital2, Patricia Fetsch3, Haresh Mani6, Daniel Zlott4, Robert Robey5, Susan E. Bates5, Xinmin Li7, Mahadev Rao1, and David S. Schrump1 Abstract Cigarette smoking at diagnosis or during therapy correlates with poor outcome in patients with lung and esophageal cancers, yet the underlying mechanisms remain unknown. In this study, we observed that exposure of esophageal cancer cells to cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) led to upregulation of the xenobiotic pump ABCG2, which is expressed in cancer stem cells and confers treatment resistance in lung and esophageal carcinomas. Furthermore, CSC increased the side population of lung cancer cells containing cancer stem cells. Upregulation of ABCG2 coincided with increased occupancy of aryl hydrocarbon receptor, Sp1, and Nrf2 within the ABCG2 promoter, and deletion of xenobiotic response elements and/or Sp1 sites markedly attenuated ABCG2 induction. Under conditions potentially achievable in clinical settings, mithramycin diminished basal as well as CSC- mediated increases in AhR, Sp1, and Nrf2 levels within the ABCG2 promoter, markedly downregulated ABCG2, and inhibited proliferation and tumorigenicity of lung and esophageal cancer cells. Microarray analyses revealed that mithramycin targeted multiple stem cell–related pathways in vitro and in vivo. Collectively, our findings provide a potential mechanistic link between smoking status and outcome of patients with lung and esophageal cancers, and support clinical use of mithramycin for repressing ABCG2 and inhibiting stem cell signaling in thoracic malignancies. -

Non-Random Aneuploidy Specifies Subgroups of Pilocytic Astrocytoma and Correlates with Older Age

www.impactjournals.com/oncotarget/ Oncotarget, Vol. 6, No. 31 Non-random aneuploidy specifies subgroups of pilocytic astrocytoma and correlates with older age Adam M. Fontebasso1,*, Margret Shirinian2,*, Dong-Anh Khuong-Quang3, Denise Bechet3, Tenzin Gayden3, Marcel Kool4, Nicolas De Jay3, Karine Jacob3, Noha Gerges3, Barbara Hutter5, Huriye Şeker-Cin4, Hendrik Witt4,6, Alexandre Montpetit7, Sébastien Brunet7, Pierre Lepage7, Geneviève Bourret7, Almos Klekner8, László Bognár8, Peter Hauser9, Miklós Garami9, Jean-Pierre Farmer10, Jose-Luis Montes10, Jeffrey Atkinson10, Sally Lambert11, Tony Kwan7, Andrey Korshunov12, Uri Tabori13, V. Peter Collins11, Steffen Albrecht14, Damien Faury3, Stefan M. Pfister4,6, Werner Paulus15, Martin Hasselblatt15, David T.W. Jones4 and Nada Jabado1,3 1 Division of Experimental Medicine, McGill University and McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 2 Department of Experimental Pathology, Immunology and Microbiology, American University Of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon 3 Departments of Pediatrics and Human Genetics, McGill University and McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 4 Division of Pediatric Neurooncology, German Cancer Research Centre (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany 5 Division of Theoretical Bioinformatics, German Cancer Research Centre (DKFZ), Heidelberg, Germany 6 Department of Pediatric Oncology, Hematology and Immunology, University of Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany 7 McGill University and Genome Quebec Innovation Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada 8 Department of Neurosurgery, -

Regulation and Function of ERK3/MK5-Mediated Signaling

Medizinische Hochschule Hannover Institut für Physiologische Chemie Regulation and Function of ERK3/MK5-mediated Signaling INAUGURAL – DISSERTATION Zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften - Doctor rerum naturalium – (Dr. rer. nat.) vorgelegt von Frank Brand geboren am 19.11.1982 in Hoyerswerda Hannover 2012 Angenommen vom Senat der Medizinischen Hochschule Hannover am 12.04.2012 Gedruckt mit Genehmigung der Medizinischen Hochschule Hannover Präsident: Prof. Dr. med Dieter Bitter-Suermann Betreuer: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Matthias Gaestel Kobetreuer: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Ernst Ungewickell 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Matthias Gaestel 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Ernst Ungewickell 3. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Andreas Kispert Tag der mündlichen Prüfung vor der Prüfungskommission: 12.04.2012 Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Matthias Gaestel Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Matthias Gaestel Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Ernst Ungewickell Prof. Dr. rer. nat. Andreas Kispert Abstract Frank Brand Title of dissertation: ‘Regulation and Function of ERK3/MK5-mediated Signaling’ The family of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated kinases (MKs, or MAPKAPKs), including the three distinct kinases MK2, MK3, and MK5, are downstream targets of the cytokine- and stress-induced p38 MAP kinases. Interaction and activation of MKs by p38 MAP kinases have been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo. The physiological relevance of the MK5/p38-interaction is doubtful, since its activity could not be triggered by any of the known MAP kinase stimuli. An interaction screen using MK5 revealed a strong binding to the atypical member of MAPKs ERK3. From previous studies, it has been concluded that MK5 is the first ‘bona fide’ substrate of ERK3, thus forming a stable complex promoting their protein stability and kinase activation. -

Androgen Receptor

RALTITREXED Dihydrofolate reductase BORTEZOMIB IsocitrateCannabinoid dehydrogenase CB1EPIRUBICIN receptor HYDROCHLORIDE [NADP] cytoplasmic VINCRISTINE SULFATE Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha DOXORUBICINAtaxin-2 HYDROCHLORIDENIFENAZONEFOLIC ACID PYRIMETHAMINECellular tumor antigen p53 Muscleblind-likeThyroidVINBURNINEVINBLASTINETRIFLURIDINE protein stimulating 1 DEQUALINIUM SULFATEhormone receptor CHLORIDE Menin/Histone-lysine N-methyltransferasePHENELZINE MLLLANATOSIDE SULFATE C MELATONINDAUNORUBICINBETAMETHASONEGlucagon-like HYDROCHLORIDEEndonuclease peptide 4 1 receptor NICLOSAMIDEDIGITOXINIRINOTECAN HYDROCHLORIDE HYDRATE BISACODYL METHOTREXATEPaired boxAZITHROMYCIN protein Pax-8 ATPase family AAA domain-containing proteinLIPOIC 5 ACID, ALPHA Nuclear receptorCLADRIBINEDIGOXIN ROR-gammaTRIAMTERENE CARMUSTINEEndoplasmic reticulum-associatedFLUOROURACIL amyloid beta-peptide-binding protein OXYPHENBUTAZONEORLISTAT IDARUBICIN HYDROCHLORIDE 6-phospho-1-fructokinaseHeat shockSIMVASTATIN protein beta-1 TOPOTECAN HYDROCHLORIDE AZACITIDINEBloom syndromeNITAZOXANIDE protein Huntingtin Human immunodeficiency virus typeTIPRANAVIR 1 protease VitaminCOLCHICINE D receptorVITAMIN E FLOXURIDINE TAR DNA-binding protein 43 BROMOCRIPTINE MESYLATEPACLITAXEL CARFILZOMIBAnthrax lethalFlap factorendonucleasePrelamin-A/C 1 CYTARABINE Vasopressin V2 receptor AMITRIPTYLINEMicrotubule-associated HYDROCHLORIDERetinoidTRIMETHOPRIM proteinMothers X receptor tau against alpha decapentaplegic homolog 3 Histone-lysine N-methyltransferase-PODOFILOX H3 lysine-9OXYQUINOLINE -

Phosphorylation Signaling in APP Processing in Alzheimer's Disease

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Phosphorylation Signaling in APP Processing in Alzheimer’s Disease Tao Zhang, Dongmei Chen and Tae Ho Lee * Fujian Key Laboratory for Translational Research in Cancer and Neurodegenerative Diseases, Institute for Translational Medicine, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Fujian Medical University, Fuzhou 350122, China; [email protected] (T.Z.); [email protected] (D.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +86-591-2286-2498 Received: 9 December 2019; Accepted: 24 December 2019; Published: 27 December 2019 Abstract: The abnormal accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) in the central nervous system is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). The regulation of the processing of the single- transmembrane amyloid precursor protein (APP) plays an important role in the generation of Aβ in the brain. The phosphorylation of APP and key enzymes involved in the proteolytic processing of APP has been demonstrated to be critical for modulating the generation of Aβ by either altering the subcellular localization of APP or changing the enzymatic activities of the secretases responsible for APP processing. In addition, the phosphorylation may also have an impact on the physiological function of these proteins. In this review, we summarize the kinases and signaling pathways that may participate in regulating the phosphorylation of APP and secretases and how this further affects the function and processing of APP and Aβ pathology. We also discuss the potential of approaches that modulate these phosphorylation-signaling pathways or kinases as interventions for AD pathology. Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease; APP processing; phosphorylation; amyloid-β; kinase 1. Introduction Current epidemiological studies estimate that there are approximately 45 million people suffering from dementia [1]. -

Proteome Analysis in a Mammalian Cell Line Reveals That PLK2 Is Involved in Avian Metapneumovirus Type C (Ampv/C)-Induced Apoptosis

viruses Article Proteome Analysis in a Mammalian Cell Line Reveals that PLK2 Is Involved in Avian Metapneumovirus Type C (aMPV/C)-Induced Apoptosis Rong Quan y, Li Wei y, Lei Hou, Jing Wang, Shanshan Zhu, Zixuan Li, Moran Lv and Jue Liu * Beijing Key Laboratory for Prevention and Control of Infectious Diseases in Livestock and Poultry, Institute of Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Medicine, Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, No. 9 Shuguang Garden Middle Road, Haidian District, Beijing 100097, China; [email protected] (R.Q.); [email protected] (L.W.); [email protected] (L.H.); [email protected] (J.W.); [email protected] (S.Z.); [email protected] (Z.L.); [email protected] (M.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-51503671; Fax: +86-10-51503498 These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 24 December 2019; Accepted: 26 March 2020; Published: 28 March 2020 Abstract: Avian metapneumovirus subtype C (aMPV/C) causes an acute respiratory disease that has caused serious economic losses in the Chinese poultry industry. In the present study, we first explored the protein profile in aMPV/C-infected Vero cells using iTRAQ quantitative proteomics. A total of 921 of 7034 proteins were identified as significantly altered by aMPV/C infection. Three selected proteins were confirmed by Western blot analysis. Bioinformatics GO analysis revealed multiple signaling pathways involving cell cycle, endocytosis, and PI3K-Akt, mTOR, MAPK and p53 signaling pathways, which might participate in viral infection. In this analysis, we found that PLK2 expression was upregulated by aMPV/C infection and investigated whether it contributed to aMPV/C-mediated cellular dysfunction. -

PLK2, Active Full Length Recombinant Protein Expressed in Sf9 Cells

Catalog # Aliquot Size P42-10G-05 5 µg P42-10G-10 10 µg PLK2, Active Full length recombinant protein expressed in Sf9 cells Catalog # P42-10G Lot # U1534-6 Product Description Specific Activity Full length recombinant human PLK2 was expressed by baculovirus in Sf9 insect cells using an N-terminal GST tag. 64,000 The gene accession number is NM_006622. 48,000 Gene Aliases 32,000 SNK 16,000 Activity (cpm) Formulation 0 0 100 200 300 400 Recombinant protein stored in 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, Protein (ng) 150mM NaCl, 10mM glutathione, 0.1mM EDTA, 0.25mM The specific activity of PLK2 was determined to be 11 nmol DTT, 0.1mM PMSF, 25% glycerol. /min/mg as per activity assay protocol. Storage and Stability Purity Store product at –70oC. For optimal storage, aliquot target into smaller quantities after centrifugation and store at recommended temperature. For most favorable performance, avoid repeated handling and multiple The purity of PLK2 was freeze/thaw cycles. determined to be >80% by densitometry, approx. MW Scientific Background ~106kDa. PLK2 or Polo-like kinase 2 is a serum-inducible kinase that is a member of the Polo family of serine/threonine protein kinases which play an essential role in normal cell division (1). PLK2 phosphorylates the P4.1-associated protein (CPAP), a human homologue of SAS-4, in procentriole PLK2, Active formation during the centrosome cycle (2). PLK2 may also Full length human recombinant protein expressed in Sf9 cells play a role as a tumor suppressor since it interacts with TSC1 protein which in turn inhibits mTOR signaling, tumor Catalog # P42-10G growth and chemosensitivity under hypoxic conditions. -

Inhibition of ERK 1/2 Kinases Prevents Tendon Matrix Breakdown Ulrich Blache1,2,3, Stefania L

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Inhibition of ERK 1/2 kinases prevents tendon matrix breakdown Ulrich Blache1,2,3, Stefania L. Wunderli1,2,3, Amro A. Hussien1,2, Tino Stauber1,2, Gabriel Flückiger1,2, Maja Bollhalder1,2, Barbara Niederöst1,2, Sandro F. Fucentese1 & Jess G. Snedeker1,2* Tendon extracellular matrix (ECM) mechanical unloading results in tissue degradation and breakdown, with niche-dependent cellular stress directing proteolytic degradation of tendon. Here, we show that the extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK) pathway is central in tendon degradation of load-deprived tissue explants. We show that ERK 1/2 are highly phosphorylated in mechanically unloaded tendon fascicles in a vascular niche-dependent manner. Pharmacological inhibition of ERK 1/2 abolishes the induction of ECM catabolic gene expression (MMPs) and fully prevents loss of mechanical properties. Moreover, ERK 1/2 inhibition in unloaded tendon fascicles suppresses features of pathological tissue remodeling such as collagen type 3 matrix switch and the induction of the pro-fbrotic cytokine interleukin 11. This work demonstrates ERK signaling as a central checkpoint to trigger tendon matrix degradation and remodeling using load-deprived tissue explants. Tendon is a musculoskeletal tissue that transmits muscle force to bone. To accomplish its biomechanical function, tendon tissues adopt a specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) structure1. Te load-bearing tendon compart- ment consists of highly aligned collagen-rich fascicles that are interspersed with tendon stromal cells. Tendon is a mechanosensitive tissue whereby physiological mechanical loading is vital for maintaining tendon archi- tecture and homeostasis2. Mechanical unloading of the tissue, for instance following tendon rupture or more localized micro trauma, leads to proteolytic breakdown of the tissue with severe deterioration of both structural and mechanical properties3–5. -

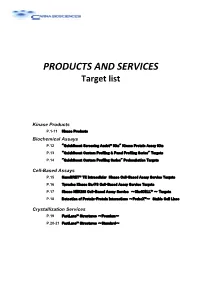

PRODUCTS and SERVICES Target List

PRODUCTS AND SERVICES Target list Kinase Products P.1-11 Kinase Products Biochemical Assays P.12 "QuickScout Screening Assist™ Kits" Kinase Protein Assay Kits P.13 "QuickScout Custom Profiling & Panel Profiling Series" Targets P.14 "QuickScout Custom Profiling Series" Preincubation Targets Cell-Based Assays P.15 NanoBRET™ TE Intracellular Kinase Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.16 Tyrosine Kinase Ba/F3 Cell-Based Assay Service Targets P.17 Kinase HEK293 Cell-Based Assay Service ~ClariCELL™ ~ Targets P.18 Detection of Protein-Protein Interactions ~ProbeX™~ Stable Cell Lines Crystallization Services P.19 FastLane™ Structures ~Premium~ P.20-21 FastLane™ Structures ~Standard~ Kinase Products For details of products, please see "PRODUCTS AND SERVICES" on page 1~3. Tyrosine Kinases Note: Please contact us for availability or further information. Information may be changed without notice. Expression Protein Kinase Tag Carna Product Name Catalog No. Construct Sequence Accession Number Tag Location System HIS ABL(ABL1) 08-001 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1) 08-401-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [E255K] HIS ABL(ABL1)[E255K] 08-094 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) HIS ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-093 Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal His Insect (sf21) ABL(ABL1) [T315I] BTN BTN-ABL(ABL1)[T315I] 08-493-20N Full-length 2-1130 NP_005148.2 N-terminal DYKDDDDK Insect (sf21) ACK(TNK2) GST ACK(TNK2) 08-196 Catalytic domain