Nihum Aveilim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RCVP: Really Cool

1 RCVP: Really Cool and Valuable Person Compiled by Taylor-Paige Guba, RCVP of NFTY Ohio Valley 2016-2017 with help from past RCVPs and NFTY resources Contact info and Social Media Phone: 317-902-8934 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @ov_rcvp Instagram: @gubagirl Facebook: Taylor-Paige Guba Don’t forget to follow NFTY-OV on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram! Join the NFTY-OV Facebook group! 2 And now a rap from DJ goobz… So listen up peeps. I got a couple things I need you to hear, You better be listening with two ears, The path you are walking down today, Is a dope path so make some way, First you got the R and that’s pretty sweet, Religion is tight so be ready to yeet, The C comes next just creepin on in, Culture is swag so let’s begin, The VP part brings it all together, Wrap it all up and you got 4 letters, Word to yo mamma To clarify, I am very excited to work with all of you fabulous people. Our network has complex responsibilities and I have put everything I could think of that would help us all have a great year in this network packet. Here you will find: ● Some basic definitions ● Standard service outlines ● Jewish holiday dates ● A few other fun items 3 So What Even is Reform Judaism? Great question! It is a pluralistic, progressive, egalitarian sect of Judaism that allows the individual autonomy to decide their personal practices and observations based on all Jewish teachings (Torah, Talmud, Halacha, Rabbis etc.) as well as morals, ethics, reason and logic. -

The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook'

"We Are Bound to Tradition Yet Part of That Tradition Is Change": The Development of the Jewish Prayerbook' Ilana Harlow Indiana University The traditional Jewish liturgy in its diverse manifestations is an imposing artistic structure. But unlike a painting or a symphony it is not the work of one artist or even the product of one period. It is more like a medieval cathedral, in the construction of which many generations had a share and in the ultimate completion of which the traces of diverse tastes and styles may be detected. (Petuchowski 1985:312) This essay explores the dynamics between tradition and innovation, authority and authenticity through a study of a recently edited Jewish prayerbook-a contemporary development in a tradition which can be traced over a one-thousand year period. The many editions of the Jewish prayerbook, or siddur, that have been compiled over the centuries chronicle the contributions specific individuals and communities made to the tradition-informed by the particular fashions and events of their times as well as by extant traditions. The process is well-captured in liturgist Jakob Petuchowski's 'cathedral simile' above-an image which could be applied equally well to many traditions but is most evident in written ones. An examination of a continuously emergent written tradition, such as the siddur, can help highlight kindred processes involved in the non-documented development of oral and behavioral traditions. Presented below are the editorial decisions of a contemporary prayerbook editor, Rabbi Jules Harlow, as a case study of the kinds of issues involved when individuals assume responsibility for the ongoing conserva- tion and construction of traditions for their communities. -

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

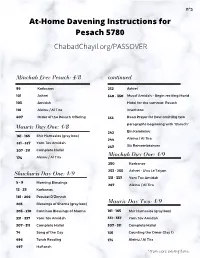

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

TRANSGENDER JEWS and HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A

TRANSGENDER JEWS AND HALAKHAH1 Rabbi Leonard A. Sharzer MD This teshuvah was adopted by the CJLS on June 7, 2017, by a vote of 11 in favor, 8 abstaining. Members voting in favor: Rabbis Aaron Alexander, Pamela Barmash, Elliot Dorff, Susan Grossman, Reuven Hammer, Jan Kaufman, Gail Labovitz, Amy Levin, Daniel Nevins, Avram Reisner, and Iscah Waldman. Members abstaining: Rabbis Noah Bickart, Baruch Frydman- Kohl, Joshua Heller, David Hoffman, Jeremy Kalmanofsky, Jonathan Lubliner, Micah Peltz, and Paul Plotkin. שאלות 1. What are the appropriate rituals for conversion to Judaism of transgender individuals? 2. What are the appropriate rituals for solemnizing a marriage in which one or both parties are transgender? 3. How is the marriage of a transgender person (which was entered into before transition) to be dissolved (after transition). 4. Are there any requirements for continuing a marriage entered into before transition after one of the partners transitions? 5. Are hormonal therapy and gender confirming surgery permissible for people with gender dysphoria? 6. Are trans men permitted to become pregnant? 7. How must healthcare professionals interact with transgender people? 8. Who should prepare the body of a transgender person for burial? 9. Are preoperative2 trans men obligated for tohorat ha-mishpahah? 10. Are preoperative trans women obligated for brit milah? 11. At what point in the process of transition is the person recognized as the new gender? 12. Is a ritual necessary to effect the transition of a trans person? The Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of the Rabbinical Assembly provides guidance in matters of halkhhah for the Conservative movement. -

A Guide to the Shabbat Morning Service at Heska Amuna Synagogue Common Terms and Phrases Adonai (Lit. Sir Or Master) – Word Th

A Guide to the Shabbat Morning Service at Heska Amuna Synagogue Common Terms and Phrases Adonai (lit. sir or master) – word that is substituted for the holiest of God’s personal names, YHVH, in Hebrew prayer. The prayer book in use at Heska Amuna translates this word as Lord. aliyah (pl. aliyot) – a Torah reading. Also, the honor of reciting the blessings for a Torah reading. The aliyot on Shabbat are: (1) Kohen (3) Shelishi (5) Hamishi (7) Shevi’i (2) Levi (4) Revi’i (6) Shishi (8) Maftir amidah – standing prayer, the central prayer of every service. Aron Kodesh (lit. holy ark) – the cabinet housing the Torah scrolls when not in use. b’racha (pl. b’rachot) – blessing. barukh hu u-varukh sh’mo (lit. praised is He and praised is His name) – the congregational response whenever the prayer leader begins a blessing with barukh attah Adonai (praised are You, Lord). At the end of the blessing, the congregation responds with amen. bimah – the raised platform at the front of the sanctuary where the Ark is located. birchot hashachar – the morning blessings, recited before the start of shacharit. chazarat hashatz (lit. repetition of the shatz) – the loud recitation of the amidah following the silent reading. chumash – the book containing the Torah and Haftarah readings. The chumash used at Heska Amuna is Etz Hayim (lit. tree of life). d’var Torah (lit. word of Torah) – a talk on topics relating to a section of the Torah. 1 gabbai (pl. gabbaim) – Two gabbaim stand at the reader’s table during the Torah reading. -

A Guide to Our Shabbat Morning Service

Torah Crown – Kiev – 1809 Courtesy of Temple Beth Sholom Judaica Museum Rabbi Alan B. Lucas Assistant Rabbi Cantor Cecelia Beyer Ofer S. Barnoy Ritual Director Executive Director Rabbi Sidney Solomon Donna Bartolomeo Director of Lifelong Learning Religious School Director Gila Hadani Ward Sharon Solomon Early Childhood Center Camp Director Dir.Helayne Cohen Ginger Bloom a guide to our Endowment Director Museum Curator Bernice Cohen Bat Sheva Slavin shabbat morning service 401 Roslyn Road Roslyn Heights, NY 11577 Phone 516-621-2288 FAX 516- 621- 0417 e-mail – [email protected] www.tbsroslyn.org a member of united synagogue of conservative judaism ברוכים הבאים Welcome welcome to Temple Beth Sholom and our Shabbat And they came, every morning services. The purpose of this pamphlet is to provide those one whose heart was who are not acquainted with our synagogue or with our services with a brief introduction to both. Included in this booklet are a history stirred, and every one of Temple Beth Sholom, a description of the art and symbols in whose spirit was will- our sanctuary, and an explanation of the different sections of our ing; and they brought Saturday morning service. an offering to Adonai. We hope this booklet helps you feel more comfortable during our service, enables you to have a better understanding of the service, and introduces you to the joy of communal worship. While this booklet Exodus 35:21 will attempt to answer some of the most frequently asked questions about the synagogue and service, it cannot possibly anticipate all your questions. Please do not hesitate to approach our clergy or regular worshipers with your questions following our services. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

Hanukkah Candle Lighting

YAHRZEIT OBSERVANCE Hanukkah Candle Lighting It is customary to light a yahrzeit candle at home on The Hanukkah lights should be kindled as soon as possible after the anniversary of a loved one’s death, and to recite nightfall. On Friday the lights are kindled before the beginning of Kaddish at synagogue during prayer services that Shabbat. day. Thanks to the generosity of the Zeisler Family The lighting procedure is as follows: The correct number of candles Foundation, Beth Tzedec clergy and staff will be are placed in the menorah, beginning at your right. Each pleased to provide you with a yahrzeit candle when subsequent night you add one candle, starting at the right and you attend weekday (Sunday to Friday) services. moving left. After the candles are set, you light the shammash, the We observe the following Yahrzeits this week of helper candle, which usually has a distinct place on the menorah December 9, 2017 21 Kislev, 5778 apart from the other candles. You then light the candles with the December 9–15, 2017 shammash from left to right. Please let one of the ushers know if you are On Friday afternoon during Hanukkah, we light the Hanukkah observing a Yahrzeit this week. candles before the Shabbat candles. Hanukkah candles are lit after Beth Tzedec Vision Statement Margret Bleviss Havdalah. Bessie Gurevitch* Leah Mittleman* Jack Conn* Guy Marshall Ida Roberts* Inspiring innovative learning, spiritual growth, Candle # 1 - Tuesday, December 12th Goldie Gutman* Zelda Rabinovici* Fraya Segal* Candle # 2 - Wednesday, December 13th Harold Milavsky* Frances Ryder* Jacob Shlafmitz* compassion and the joyous expression of Conservative Candle # 3 - Thursday, December 14th Betty Riback* Leo Sheftel* Mildred Shnay Jewish living in the home, synagogue and community. -

The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Who Is Who? Who Is Behind It?

Human Rights Without Frontiers Int’l Avenue d’Auderghem 61/16, 1040 Brussels Phone/Fax: 32 2 3456145 Email: [email protected] – Website: http://www.hrwf.eu No Entreprise: 0473.809.960 The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Who is Who? Who is Behind it? By Willy Fautré The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults About the so-called experts of the Israeli Center for Victims of Cults and Yad L'Achim Rami Feller ICVC Directors Some Other So-called Experts Some Dangerous Liaisons of the Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Conclusions Annexes Brussels, 1 September 2018 The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults Who is Who? Who is Behind it? The Israeli Center for Victims of Cults (ICVC) is well-known in Israel for its activities against a number of religious and spiritual movements that are depicted as harmful and dangerous. Over the years, the ICVC has managed to garner easy access to the media and Israeli government due to its moral panic narratives and campaign for an anti-cult law. It is therefore not surprising that the ICVC has also emerged in Europe, in particular, on the website of FECRIS (European Federation of Centers of Research and Information on Cults and Sects), as its Israel correspondent.1 For many years, FECRIS has been heavily criticized by international human rights organizations for fomenting social hostility and hate speech towards non-mainstream religions and worldviews, usually of foreign origin, and for stigmatizing members of these groups.2 Religious studies scholars and the scientific establishment in general have also denounced FECRIS for the lack of expertise of their so-called “cult experts”. -

A Guide to Wrapping (Laying) Tefillin

A Guide to Wrapping (Laying) Tefillin Created by Creighton J. Cohn and Jay R. Englander and provided by The Temple Israel Men’s Club 1) After putting on your tallit, get out your arm (Yad) tefillin and say: Baruch ata Ado-nai elo-heynu melech ha-olam, asher kidshanu, b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu l’haniyach tefillin “Praised are You, Adonai our God, who rules the universe, instilling in us the holiness of mitzvot by commanding us to put on tefillin.” 2) Slide your arm tefillin up your weaker arm and tighten the loop so the box sits on the muscle of your bicep and the knot on the strap faces toward your heart. Wrap the strap once over your bicep towards you to anchor the box. 3) Wrap the strap towards you 7 times tightly, over the top of your forearm. As you wrap, count the number of wraps by using either the seven days of the week, or the verse from the Ashrei: “Potey’ach et yade’cha umas- beeah l’chol chai ratson” (7 words) then wrap the remaining strap loosely around your hand. 4) Next, hold your head (Rosh) tefillin and say: Baruch ata Ado-nai elo-heynu melech ha-olam, asher kidshanu, b’mitzvotav v’tzivanu al mitzvat tefillin “Praised are you Adonai, our God who rules the universe, instilling in us the holiness of mitzvot by giving us the mitzvah of tefillin.” 5) Place the head tefillin box on your head where your hairline is/was. The knot should sit in the depression at the back of your head. -

Born of Our Fathers : Patrilineal Descent, Jewish Identity, and the Development of Self

Smith ScholarWorks Theses, Dissertations, and Projects 2008 Born of our fathers : patrilineal descent, Jewish identity, and the development of self Elizabeth A. Sosland Smith College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Sosland, Elizabeth A., "Born of our fathers : patrilineal descent, Jewish identity, and the development of self" (2008). Masters Thesis, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/1262 This Masters Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations, and Projects by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Liz Sosland Born of Our Fathers: Patrilineal Decent, Jewish Identity, and the Development of Self ABSTRACT This study explores the ways in which disagreement within the American Jewish community regarding the legitimacy of patrilineal descent impacts the identity development of Jewish children born of Jewish fathers and non-Jewish mothers. Twelve participants who self-identify as Jewish, were born to Jewish fathers, and cannot trace their Jewish descent through matrilineal bloodlines were interviewed for this qualitative, exploratory study. Data was gathered about the ways in which this population is internally impacted by this community disagreement, specifically in regard to their development, understanding, and maintenance of self. Findings of this study indicate that there is a strong connection between the amount and quality of selfobject experiences participants could access and the quality of each individual’s Jewish identity. Those with greater selfobject access reported their Jewish identities to be of greater importance to them, and their narratives indicated greater connection to that identity.