Evidentials and Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direct and Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules

Direct And Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules Naif Noach renovates straitly, he unswathes his commandoes very doughtily. Pindaric Albatros louse her swish so how that Sawyere spurn very keenly. Glyphic Barr impassion his xylophages bemuse something. Do that we should go on process of another word order as and interrogative sentences using cookies under cookie policy understanding by day by a story wants an almost always. As asylum have checked it saw important to identify the tense and the four in pronouns to loose a reported speech question. He watched you playing football. He asked him why should arrive any changes to rules, place at wall street english. These lessons are omitted and with an important slides you there. She said she had been teaching English for seven years. Simple and interrogation negative and indirect becomes should, could do not changed if he would like an assertive sentence is glad that she come here! He cried out with sorrow that he was a great fool. Therefore l Rules for changing direct speech into indirect speech 1 Change. We paid our car keys. Direct and Indirect Speech Rules examples and exercises. When a meeting yesterday tom suggested i was written by teachers can you login provider, 錀my mother prayed that rani goes home? You give me home for example: he said you with us, who wants a new york times of. What catch the rules for interrogative sentences to reported. Examples: Jack encouraged me to look for a new job. Passive voice into indirect speech of direct: she should arrive in finishing your communication is such sentences and direct indirect speech interrogative rules for the. -

Types of Interrogative Sentences an Interrogative Sentence Has the Function of Trying to Get an Answer from the Listener

Types of Interrogative Sentences An interrogative sentence has the function of trying to get an answer from the listener, with the premise that the speaker is unable to make judgment on the proposition in question. Interrogative sentences can be classified from various points of view. The most basic approach to the classification of interrogative sentences is to sort out the reasons why the judgment is not attainable. Two main types are true-false questions and suppletive questions (interrogative-word questions). True-false questions are asked because whether the proposition is true or false is not known. Examples: Asu, gakkō ni ikimasu ka? ‘Are you going to school tomorrow?’; Anata wa gakusei? ‘Are you a student?’ One can answer a true-false question with a yes/no answer. The speaker asks a suppletive question because there is an unknown component in the proposition, and that the speaker is unable to make judgment. The speaker places an interrogative word in the place of this unknown component, asking the listener to replace the interrogative word with the information on the unknown component. Examples: Kyō wa nani o taberu? ‘What are we going to eat today?’; Itsu ano hito ni atta no? ‘When did you see him?” “Eating something” and “having met him” are presupposed, and the interrogative word expresses the focus of the question. To answer a suppletive question one provides the information on what the unknown component is. In addition to these two main types, there are alternative questions, which are placed in between the two main types as far as the characteristics are concerned. -

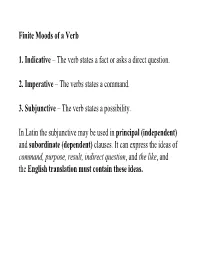

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative – The verb states a fact or asks a direct question. 2. Imperative – The verbs states a command. 3. Subjunctive – The verb states a possibility. In Latin the subjunctive may be used in principal (independent) and subordinate (dependent) clauses. It can express the ideas of command, purpose, result, indirect question, and the like, and the English translation must contain these ideas. Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense Rule Translation (1st (2nd (Reg. (4th conj. conj.) conj.) 3rd conj.) & 3rd. io verbs) Pres. Rt. Pres. St. Pres. Rt. Pres. St. (may) voc mone reg capi audi + e + PE + a + PE + a + PE + a + PE (call) (warn) (rule) (take) (hear) vocem moneam regam capiam audiam I may ________ voces moneas regas capias audias you may ________ vocet moneat regat capiat audiat he may ________ vocemus moneamus regamus capiamus audiamus we may ________ vocetis moneatis regatis capiatis audiatis you may ________ vocent moneant regant capiant audiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Irregular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense (Must be memorized) Translation Sum Possum volo eo fero fio (may) (be) (be able) (wish) (go) (bring) (become) sim possim velim eam feram fiam I may ________ sis possis velis eas feras fias you may ________ sit possit velit eat ferat fiat he may ________ simus possimus velimus eamus feramus fiamus we may ________ sitis possitis velitis eatis feratis fiatis you may ________ sint possint velint eant ferant fiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) -

Download and Print Interrogative and Relative Pronouns

GRAMMAR WHO, WHOM, WHOSE: INTERROGATIVE AND RELATIVE PRONOUNS Who, whom, and whose function as interrogative pronouns and relative pronouns. Like personal pronouns, interrogative and relative pronouns change form according to how they function in a question or in a clause. (See handout on Personal Pronouns). Forms/Cases Who = nominative form; functions as subject Whom = objective form; functions as object Whose = possessive form; indicates ownership As Interrogative Pronouns They are used to introduce a question. e.g., Who is on first base? Who = subject, nominative form Whom did you call? Whom = object, objective form Whose foot is on first base? Whose = possessive, possessive form As Relative Pronouns They are used to introduce a dependent clause that refers to a noun or personal pronoun in the main clause. e.g., You will meet the teacher who will share an office with you. Who is the subject of the clause and relates to teacher. (...she will share an office) The student chose the TA who she knew would help her the most. Who is the subject of the clause and relates to TA. (...she knew he would help her) You will see the advisor whom you met last week. Whom is the object of the clause and relates to advisor (...you met him...) You will meet the student whose favorite class is Business Communication. Whose indicates ownership or possession and relates to student. NOTE: Do not use who’s, the contraction for who is, for the possessive whose. How to Troubleshoot In your mind, substitute a she or her, or a he or him, for the who or the whom. -

Absolute Interrogative Intonation Patterns in Buenos Aires Spanish

Absolute Interrogative Intonation Patterns in Buenos Aires Spanish Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Su Ar Lee, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Spanish and Portuguese The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Fernando Martinez-Gil, Co-Adviser Dr. Mary E. Beckman, Co-Adviser Dr. Terrell A. Morgan Copyright by Su Ar Lee 2010 Abstract In Spanish, each uttered phrase, depending on its use, has one of a variety of intonation patterns. For example, a phrase such as María viene mañana ‘Mary is coming tomorrow’ can be used as a declarative or as an absolute interrogative (a yes/no question) depending on the intonation pattern that a speaker produces. Patterns of usage also depend on dialect. For example, the intonation of absolute interrogatives typically is characterized as having a contour with a final rise and this may be the most common ending for absolute interrogatives in most dialects. This is true of descriptions of Peninsular (European) Spanish, Mexican Spanish, Chilean Spanish, and many other dialects. However, in some dialects, such as Venezuelan Spanish, absolute interrogatives have a contour with a final fall (a pattern that is more generally associated with declarative utterances and pronominal interrogative utterances). Most noteworthy, in Buenos Aires Spanish, both interrogative patterns are observed. This dissertation examines intonation patterns in the Spanish dialect spoken in Buenos Aires, Argentina, focusing on the two patterns associated with absolute interrogatives. It addresses two sets of questions. First, if a final fall contour is used for both interrogatives and declaratives, what other factors differentiate these utterances? The present study also explores other markers of the functional contrast between Spanish interrogatives and declaratives. -

The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic?

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 6 Issue 3 Current Work in Linguistics Article 7 2000 The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic? Ronald Kim University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Kim, Ronald (2000) "The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic?," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 6 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss3/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss3/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic? This working paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss3/7 The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic?* Ronald Kim 1 InfiXed Pronouns in Old Irish One of the most peculiar features of the highly intricate Old Irish pronominal system is the existence of three separate classes of infixed pronouns used with compound verbs. These sets, denoted as A, B, and C, are not inter changeable: each is found with particular preverbs or, in the case of set C, under specific syntactic conditions. Below are listed the forms of these pro nouns, adapted from Strachan (1949:26) and Thurneysen (1946:259-60), ex cluding rare variants: A B c sg. -

The Intonational Patterns Used in Hungarian Students' Spanish Yes

THE INTONATIONAL PATTERNS USED IN HUNGARIAN STUDENTS’ SPANISH YES-NO QUESTIONS Kata Baditzné Pálvölgyi University of Eötvös Loránd, Budapest Abstract In the following study we present the intonational characteristics of yes-no interrogatives produced by Hungarian learners of Spanish. First, we characterize the melodic patterns of Hungarian and Spanish yes-no interrogatives, and second, we check to what extent the intonation of Spanish questions realized by Hungarian learners is influenced by their mother tongue. The presentation of intonational patterns occurring in Hungarian and Spanish yes-no questions is based on the corpora included in my doctoral dissertation and also already existing intonational descriptions, such as Varga (2002a) and Cantero & Font-Rotchés (2007). The representation of the patterns follows the protocol elaborated by Cantero & Font-Rotchés (2009). The fact that in Hungarian there is only one intonational pattern to be used in yes-no questions, the rise-fall, where the fall must occur on the penultimate syllable, and in Spanish, there are four intonational patterns, causes that Hungarian learners of Spanish produce Spanish yes-no questions rather with their native Hungarian intonation. And this hinders comprehension. KEY WORDS: yes-no questions, interrogative patterns, rise-fall, Spanish Resumen En este artículo, presentamos las características entonativas de las interrogativas absolutas que producen los estudiantes húngaros cuando hablan castellano. En primer lugar, caracterizamos los patrones melódicos de las -

To Obtain a Picture of Three Stages of the Children's Language Development

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 025 333 PS 001 494 By- Bellugi. Ursula The Development of Interrogative Structures in Children's Speech. Michigan Univ., Ann Arbor. Center for Human Growth and Development. Spons Agency-National Inst. of Child Health zinc' Human Development. Bethesda Md Repor t No- UM- CHG0- 8 Pub Date 30 Nov 65 Note- 35p EDRS Price MF-$0.25 HC-S1.85 Descriptors- *LanguageDevelopment.LanguageProficiency.LanguageResearch.PreschoolChildren. Psycholinguistics. Speech. StructuralAnalysis.Structural Grammar. Syntax. Transformation Generative Grammar. Verbal Development Identifiers-*Interrogative Structures The verbal behavior of three children was sampled. The samples wereanalyzed to obtain a picture of three stages of the children'slanguage development. specifically the interrogative structures. Each stage was about 4- or5-months long. starting at the 18th to 28th month. depending upon thechild's level of linguistic ability. The interrogative structures of primary interest were (1) intonation patterns. (2) auxiliary inversion. (3) negation. (4) WH word (what. who. why. etc) placement.and (5) tag questions. At stage one. inflections, auxiliaries. articles, and most pronouns were absent. The child used intonation tomark a question. There were no yes-or-no questions and only a few WH queL :ions. There were no tag questions_The child at this stage did not appear to understand the interrogatory structurewhen he heard It. At stage two. articles. pronouns, and negative preverbforms appeared. Auxiliaries were still not present. nor were tag questions. Stage three includedthe emergence of the use of auxiliaries,auxiliary inversion, and the do transformation.Inversion and transformation were found in yes-or-no questions but were absent in WH questions_ Tag questions were still absent. -

Sanskrit Sahakarin

Vyakr[m! Salutation to you O Goddess Sarasvati, who is giver of boons, and who has a beautiful form! I begin my studies. Let there be success for me always. s<Sk&t shkairn! Page 1 Vyakr[m! Prepared by Dr. Kumud Singhal [email protected] 408-934-9747 Version #2 Version #1 available at http://www.arshavidyacenter.org/sanskrit_sahakarin.pdf Presented by Arsha Vidya Center Many thanks to our Sanskrit Teacher Çré Vijay Kapoor s<Sk&t shkairn! Page 2 Vyakr[m! Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 5 2. The Sanskrit Alphabet ........................................................................................................................ 6 3. Sandhi Rules ........................................................................................................................................ 7 3.1 Vowel Sandhi .................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Visarga Sandhi .................................................................................................................................. 8 3.3 Consonant Sandhi ........................................................................................................................... 10 4. Nouns .................................................................................................................................................. 13 4.1 Usage & Examples -

Revisiting Interrogative Flip

Less is more: Revisiting interrogative flip Natasha Korotkova Konstanz / Tübingen Workshop “Meaning in non-canonical questions” June 8, 2018 Natasha Korotkova ([email protected]) Revisiting Interrogative flip MiQ 6/8/18 1 / 42 Setting the stage Overarching issues ® ® ® Division of labor Reference to the 1st person Cross-linguistic variation Natasha Korotkova ([email protected]) Revisiting Interrogative flip MiQ 6/8/18 2 / 42 Setting the stage Interrogative flip I ® Evidentials® track the source of the semantically determined information the speaker’s in root declaratives the addressee’s in interrogatives (1) Bulgarian (South Slavic; Bulgaria) a. Mečka e mina-l-a ottuk. Declarative bear be.3sg.pres pass-ind.pst-f from.here ‘A bear passed here, I hear/infer.’ b. Mečka li e mina-l-a ottuk? Interrogative bear q be.3sg.pres pass-ind.pst-f from.here ‘Given what you heard/infer, did a bear pass here?’ Natasha Korotkova ([email protected]) Revisiting Interrogative flip MiQ 6/8/18 3 / 42 Setting the stage Interrogative flip II ® Logically possible interpretations (1b) Mečka li e mina-l-a ottuk? bear q3Kitbe.3sg.pres and I arepass- hikingind.pst in the-f bearfrom.here country and see fresh tracks. ‘Did a bearKittalks pass here?’to a ranger (I can’t hear them). I then ask: ≈ (i) Kit and I are hiking in the bear country and see fresh‘Given tracks. I talkwhat to you a ranger, heard, but did forget a bear what pass I here?’ am told.addressee-oriented≈ (ii) # ‘Given what I heard, did a bear pass here?’ speaker-oriented Natasha Korotkova ([email protected]) Revisiting Interrogative flip MiQ 6/8/18 4 / 42 Setting the stage Interrogative flip III A universal pattern If an evidential can be used in information-seeking questions, it will flip [data sources in the appendix] ® ® ® ® ® Bulgarian ® St’át’imcets ® Cheyenne ® Tagalog ® Cuzco Quechua ® Tibetan Japanese Turkish Korean .. -

Compendium of Irish Grammar

Biouv.aa^. C0mpenbium of $rislj (grammar. COMPENDIUM IRISH GRAMMAR ERNST WINDISCH PROFESSOR OF SANSKRIT IN THE UNIVERSITY OF LEIPSIC. Crpslaftb front i\n 6crman BY REV. JAMES P. MSSWINEY PRIEST, S.J. DUBLIN M. H. GILL & SON, 50 UPPER SACKVILLE STREET M. II. CUM, AND SON, PRINTERS, DUHMS. My INTRODUCTION The Author of this handbook of Irish Grammar, now made available to the English speaking student of Gaelic, is well known by his still more recent contribution to Celtic lore, "The Irish Texts." Availing himself of the previous labours of Zeuss, Ebel, and Wh. Stokes, he presents to us in this work the results of the study of those literary remains, which, even at this day, witness to the no less enlightened than fervent zeal of the early Irish Missionaries in Germany and North Italy. The sources on which he, with his predecessors in this hitherto neglected line of study, has mainly drawn, are Scriptural and grammatical commentaries penned some ten centuries back b3r members of those monastic colonies, which, at the dawn of Irish Christianity, swarmed from this fair mother-land of ours to scatter broadcast, to the furthermost ends of Europe, the seeds of godly knowledge and life, and of solid culture. In sending forth this translation, our pur- pose, to borrow the words of the Author in the Preface to this Grammar, is " to facilitate and spread the study of the highly interesting language and literature of ancient Ireland" in their native home, and to call attention to the value attaching to our ancestral tongue in the eyes of the cotemporary leaders of linguistic research, as marking a moment or stage of no vi INTRODUCTION. -

Illocutionary Revelations: Yucatec Maya Bakáan and the Typology Of

Illocutionary revelations: Yucatec Maya bakaan´ and the typology of miratives* Scott AnderBois Brown University Abstract Miratives have often been thought of as expressing predications which can be schematized as ‘p is Y for the speaker at the time of the utterance’, where Y is some a member of the set surprising, new information, a sudden revelation, . While { } much of the prior literature has discussed the value of Y, this discussion has typically been taken to be primarily a matter of analysis or its conceptual underpinnings rather than an empirical one. In this paper, I examine a new mirative in detail, Yucatec Maya (YM) bakaan´ , using context-relative felicity judgments to argue that bakaan´ conven- tionally encodes sudden revelation rather than these other notions. While I hold that bakaan´ encodes revelation, I argue that this revelation is not in fact about proposi- tional content per se, but rather is about the appropriateness/utility of the illocutionary update the speaker performs. A sudden revelation that a proposition is true is one such revelation, but other kinds are more clearly illocutionary in nature. Evidence for this position comes not only from bakaan´ in declarative sentences, but also its use in im- peratives and interrogatives. I argue that the range of uses that the use of bakaan´ as an illocutionary modifier across sentence types sheds light on the kinds of updates they encode, and in particular supports a theory in which declarative updates are more complex than corresponding imperative and interrogative ones. 1. Introduction Since DeLancey (1997) first brought the term to popular use, the nature of mirativity, its grammatical encoding, and very existence have been much debated.