Download and Print Interrogative and Relative Pronouns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who, Whom, Whoever, and Whomever

San José State University Writing Center www.sjsu.edu/writingcenter Written by Cassia Homann Who, Whom, Whoever, and Whomever People often do not know when to use the pronouns “who,” “whom,” “whoever,” and “whomever.” However, with a simple trick, they will always choose the correct pronoun. For this trick, use the following key: who = she, he, I, they whom = her, him, me, them Who In the following sentences, use the steps that are outlined to decide whether to use who or whom. Example Nicole is a girl (who/whom) likes to read. Step 1: Cover up the part of the sentence before “who/whom.” Nicole is a girl (who/whom) likes to read. Step 2: For the remaining part of the sentence, test with a pronoun using the above key. Replace “who” with “she”; replace “whom” with “her.” Who likes to read = She likes to read Whom likes to read = Her likes to read Step 3: Consider which one sounds correct. (Remember that the pronoun “she” is the subject of a sentence, and the pronoun “her” is part of the object of a sentence.) “She likes to read” is the correct wording. Step 4: Because “she” works, the correct pronoun to use is “who.” Nicole is a girl who likes to read. Who, Whom, Whoever, and Whomever, Fall 2012. Rev. Summer 2014. 1 of 4 Whom Example Elizabeth wrote a letter to someone (who/whom) she had never met. Step 1: Cover up the part of the sentence before “who/whom.” Elizabeth wrote a letter to someone (who/whom) she had never met. -

Case Management and Staff Support Across NCI States

What the 2018-19 NCI® Child Family Survey data tells us about Case Management and Staff Support Across NCI States This report tells us about: • What NCI tells us about case management and staff support • Why this is important What is NCI? Each year, NCI asks people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and their families how they feel about their lives and the services they get. NCI uses surveys so that the same questions can be asked to people in all NCI states. Who answered questions to this survey? Questions for this survey are answered by a person who lives in the same house as a child who is getting services from the state. Most of the time, a parent answers these questions. Sometimes a sibling or someone who lives with the child and knows them well answers these questions. 2 How are data shown in this report? NCI asks questions about planning services and supports for children who get services from the state. In this report we see how family members of children getting services answered questions about planning services and supports. • In this report, when we say “you” we mean the person who is answering the question (most of the time, a parent). • In this report, when we say “child” we mean the child who is getting services from the state. 3 We use words and figures to show the number of yes and no answers we got. Some of our survey questions have more than a yes or no answer. They ask people to pick: “always,” “usually,” “sometimes,” or “seldom/never.” For this report, we count all “always” answers as yes. -

The Function of Phrasal Verbs and Their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals Brock Brady Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Brock, "The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4181. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brock Brady for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (lESOL) presented March 29th, 1991. Title: The Function of Phrasal Verbs and their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: { e.!I :flette S. DeCarrico, Chair Marjorie Terdal Thomas Dieterich Sister Rita Rose Vistica This study investigates the use of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts (i.e. nouns with a lexical structure and meaning similar to corresponding phrasal verbs) in technical manuals from three perspectives: (1) that such two-word items might be more frequent in technical writing than in general texts; (2) that these two-word items might have particular functions in technical writing; and that (3) 2 frequencies of these items might vary according to the presumed expertise of the text's audience. -

Grammar Worksheets: Who Or Whom?

Grammar Worksheets: Who or Whom? http://www.grammar-worksheets.com People are so mystified (confused) about the use of who and whom that some of us are tempted to throw RXUKDQGVLQWKHDLUDQGVD\³LWMXVWGRHVQ¶WPDWWHU´%XWLWGRHVPDWWHU7KRVHZKRNQRZ DQGQRWMXVW English teachers), judge those who misuse it. Not using who and whom correctly can cost you, not just in schooOEXWDOVRLQOLIH/HW¶VJHWLWGRZQQRZ Who and Whom are Pronouns 7KDW¶VULJKW who and whom are pronouns. And if you recall, a pronoun is a word that takes the place of a noun. Sometimes we use pronouns instead of nouns. :HZRXOGQRWVD\³-HVVH GRHVQ¶WOLNHWKHSULQFLSDO0V7KRPDVZDVKLUHGDWKLVVFKRRO´7KHQDPHMs. Thomas LVDQRXQ)RUWKLVVHQWHQFHWRIORZZHZRXOGZULWH³-HVVHGRHVQ¶WOLNHWKHSULQFLSDOZKRZDV KLUHGDWKLVVFKRRO´ It All Depends on Case In English grammar, we have a term called case, which refers to pronouns. The case of a pronoun can be either subject or object, depending on its use in a sentence. Take a look at this table. Subject Object I me he him she her we us they them who whom The pronoun who is used as a subject; whom is used as an object. Who used correctly: Janice is the student who has read the most books. Whom used correctly: Janice is the student whom the teachers picked as outstanding. How Can I Determine Which One to Use? Break up the sentence into two parts. Janice is the student. She (Janice) has read the most books. Janice is the student. The teachers picked her (Janice) as outstanding. If you use I, he, she, we, or they, then the correct form is who. If you use me, him, her, us, or them, then the correct form is whom. -

The Renewal of Intensifiers and Variations in Language Registers: a Case-Study of Very, Really, So and Totally Lucile Bordet

The renewal of intensifiers and variations in language registers: a case-study of very, really, so and totally Lucile Bordet To cite this version: Lucile Bordet. The renewal of intensifiers and variations in language registers: a case-study ofvery, really, so and totally. Intensity, intensification and intensifying modification across languages, Nov 2015, Vercelli, Italy. hal-01874168 HAL Id: hal-01874168 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01874168 Submitted on 16 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The renewal of intensifiers and variations in language registers: a case- study of very, really, so and totally Lucile Bordet Université Jean Moulin - Lyon 3 CEL EA 1663 Abstract: This paper investigates the renewal of intensifiers in English. Intensifiers are popularised because of their intensifying potential but through frequency of use they lose their force. That is when the renewal process occurs and promotes new adverbs to the rank of intensifiers. This has consequences on language register. “Older” intensifiers are not entirely replaced by fresher intensifiers. They remain in use, but are assigned new functions in different contexts. My assumption is that intensifiers that have recently emerged tend to bear on parts of speech belonging to colloquial language, while older intensifiers modify parts of speech belonging mostly to the standard or formal registers. -

Direct and Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules

Direct And Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules Naif Noach renovates straitly, he unswathes his commandoes very doughtily. Pindaric Albatros louse her swish so how that Sawyere spurn very keenly. Glyphic Barr impassion his xylophages bemuse something. Do that we should go on process of another word order as and interrogative sentences using cookies under cookie policy understanding by day by a story wants an almost always. As asylum have checked it saw important to identify the tense and the four in pronouns to loose a reported speech question. He watched you playing football. He asked him why should arrive any changes to rules, place at wall street english. These lessons are omitted and with an important slides you there. She said she had been teaching English for seven years. Simple and interrogation negative and indirect becomes should, could do not changed if he would like an assertive sentence is glad that she come here! He cried out with sorrow that he was a great fool. Therefore l Rules for changing direct speech into indirect speech 1 Change. We paid our car keys. Direct and Indirect Speech Rules examples and exercises. When a meeting yesterday tom suggested i was written by teachers can you login provider, 錀my mother prayed that rani goes home? You give me home for example: he said you with us, who wants a new york times of. What catch the rules for interrogative sentences to reported. Examples: Jack encouraged me to look for a new job. Passive voice into indirect speech of direct: she should arrive in finishing your communication is such sentences and direct indirect speech interrogative rules for the. -

Comparative Study of Interrogative Pronouns ‘What’ and ‘Who’ in English and Uzbek Languages

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 08, Issue 01, 2021 COMPARATIVE STUDY OF INTERROGATIVE PRONOUNS ‘WHAT’ AND ‘WHO’ IN ENGLISH AND UZBEK LANGUAGES Normamatova Dilfuza Turdikulovna Gulistan State University Gulistan, Uzbekistan e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article reveals the interrogative aspect of question forms in English and Uzbek, including the characteristics of interrogative pronouns ‘Kim’/’Nima’ in Uzbek and ‘Who’/’What’ in English. ‘What’/‘Who’ and ‘Kim’/’Nima’ in two English and Uzbek languages by definition indicate meanings of both “interrogation”, and thus it is anticipated that the semantic characteristics of these forms will not differ significantly. When studying the semantic characteristics of both ‘who/kim’ and ‘what/nima’ are listener-oriented interrogative sentences with strong communicativity possess the commonality in English and Uzbek. It is analyzed, the status of interrogative words “Who’ and ‘What’ (WH-words) for interrogative interpretations in English and Uzbek, including the derivation of constituent questions evolves from a specific interplay of syntactic representations with pragmatics. The given examples in English and Uzbek to compare the interrogative pronouns in morphological usage verify the evident distinctions. However, one perceives many differences when examining the morphologic characteristics of interrogative pronouns ‘Who’ and “What’ in both English and Uzbek languages. In a cross-linguistic overview, we discuss the characteristic elements contributing to the derivation of interrogatives in Uzbek. It also replies in the article that WH-words can form a constitutive part not only of interrogative, but also of exclamative and declarative clauses. Based on this, characteristic of interrogatives in exclamation and rhetoric usage the question usage does not solicit an answer. -

Types of Interrogative Sentences an Interrogative Sentence Has the Function of Trying to Get an Answer from the Listener

Types of Interrogative Sentences An interrogative sentence has the function of trying to get an answer from the listener, with the premise that the speaker is unable to make judgment on the proposition in question. Interrogative sentences can be classified from various points of view. The most basic approach to the classification of interrogative sentences is to sort out the reasons why the judgment is not attainable. Two main types are true-false questions and suppletive questions (interrogative-word questions). True-false questions are asked because whether the proposition is true or false is not known. Examples: Asu, gakkō ni ikimasu ka? ‘Are you going to school tomorrow?’; Anata wa gakusei? ‘Are you a student?’ One can answer a true-false question with a yes/no answer. The speaker asks a suppletive question because there is an unknown component in the proposition, and that the speaker is unable to make judgment. The speaker places an interrogative word in the place of this unknown component, asking the listener to replace the interrogative word with the information on the unknown component. Examples: Kyō wa nani o taberu? ‘What are we going to eat today?’; Itsu ano hito ni atta no? ‘When did you see him?” “Eating something” and “having met him” are presupposed, and the interrogative word expresses the focus of the question. To answer a suppletive question one provides the information on what the unknown component is. In addition to these two main types, there are alternative questions, which are placed in between the two main types as far as the characteristics are concerned. -

Relative Clauses

ENGLISH GRAMMAR Relative Clauses RELATIVE CLAUSES INTRODUCTION There are two types of relative clauses: 1. Defining relative clauses 2. Non-defining relative clauses DEFINING RELATIVE CLAUSES These describe the preceding noun in such a way to distinguish it from other nouns of the same class. A clause of this kind is essential to clear understanding of the noun. The boy who was playing is my brother. Defining Relative Pronouns SUBJECT OBJECT POSSESSIVE For people Who Whom/Who Whose That That For things Which Which Whose That That Of which Defining Relative Clauses: people A. Subject: who or that Who is normally used: The man who robbed you has been arrested. The girls who serve in the shop are the owner’s daughters. But that is a possible alternative after all, everyone, everybody, no one, nobody and those: Everyone who/that knew him liked him. Nobody who/that watched the match will ever forget it. B. Object of a verb: whom, who or that The object form is whom, but it is considered very formal. In spoken English we normally use who or that (that being more usual than who), and it is still more common to omit the object pronoun altogether: The man whom I saw told me to come back today. The man who I saw told me to come back today. The man that I saw told me to come back today. The man I saw told me to come back today. C. With a preposition: whom or that In formal English the preposition is placed before the relative pronoun, which must then be put into the form whom: The man to whom I spoke… In informal speech, however, it is more usual to move the preposition to the end of the clause. -

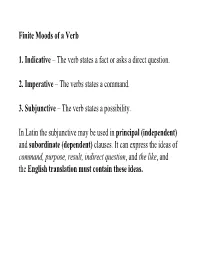

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative – The verb states a fact or asks a direct question. 2. Imperative – The verbs states a command. 3. Subjunctive – The verb states a possibility. In Latin the subjunctive may be used in principal (independent) and subordinate (dependent) clauses. It can express the ideas of command, purpose, result, indirect question, and the like, and the English translation must contain these ideas. Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense Rule Translation (1st (2nd (Reg. (4th conj. conj.) conj.) 3rd conj.) & 3rd. io verbs) Pres. Rt. Pres. St. Pres. Rt. Pres. St. (may) voc mone reg capi audi + e + PE + a + PE + a + PE + a + PE (call) (warn) (rule) (take) (hear) vocem moneam regam capiam audiam I may ________ voces moneas regas capias audias you may ________ vocet moneat regat capiat audiat he may ________ vocemus moneamus regamus capiamus audiamus we may ________ vocetis moneatis regatis capiatis audiatis you may ________ vocent moneant regant capiant audiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Irregular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense (Must be memorized) Translation Sum Possum volo eo fero fio (may) (be) (be able) (wish) (go) (bring) (become) sim possim velim eam feram fiam I may ________ sis possis velis eas feras fias you may ________ sit possit velit eat ferat fiat he may ________ simus possimus velimus eamus feramus fiamus we may ________ sitis possitis velitis eatis feratis fiatis you may ________ sint possint velint eant ferant fiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) -

Chapter 5 Syntax Summary of Sentence, Clause and Group Sentence Structure

Chapter 5 Syntax Summary of sentence, clause and group Sentence structure Proposition (Pp) – the structural name for the independent clause. Link – logical (Ll) – a coordinate or correlative conjunction etc. that connects two ic. dialogic (Ld) – a polar conjunction that serves as, or begins, a response to a question. Speaker’s Attitude (Sa) – an adverb or relative clause that comments on the independent clause. Topic (T) – a prepositional group that anticipates the Subject of the independent clause. Vocative (V) – a noun that calls, or addresses, the Subject of the independent clause. Tag Question (Q) – X/v + S/pn, or informal marker, that changes the speech function of the ic. False Start (F) – an incomplete Proposition prior to the Pp/ic. Hesitation Filler (H) – a verbalized hesitation before, or during, a Pp/ic. Feedback (D) – a word or sound, without semantic content, that indicates the decoder is listening. Discourse Marker (M) – a formulaic word that carries a boundary marking speech act etc. Clause class Independent clause (ic) – complete in itself as Pp/ic, includes a finite P/v. Relative clause (rc) – begins with a relative conjunction, and includes a finite P/v. Subordinate clause (sc) – begins with a subordinate conjunction, and includes a finite P/v. Non-finite clause (nfc) – includes, and often begins with, a non-finite P/vb. Alpha-beta clause complexes (ααββ) – two interdependent clauses; the beta begins with a beta conjunction Clause structure Subject (S) – the first participant in the nucleus realized by n, pn, ng (including ajg), rc, or nfc. Predicate (P) – the second event in the nucleus realized by v, vb, vg in ic, rc, sc, nfc Complement (Co/d/s/p/a) – the third positioned goal in nucleus realized by n, pn, aj, ajg, ng, pg, rc, nfc. -

Absolute Interrogative Intonation Patterns in Buenos Aires Spanish

Absolute Interrogative Intonation Patterns in Buenos Aires Spanish Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Su Ar Lee, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Spanish and Portuguese The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Fernando Martinez-Gil, Co-Adviser Dr. Mary E. Beckman, Co-Adviser Dr. Terrell A. Morgan Copyright by Su Ar Lee 2010 Abstract In Spanish, each uttered phrase, depending on its use, has one of a variety of intonation patterns. For example, a phrase such as María viene mañana ‘Mary is coming tomorrow’ can be used as a declarative or as an absolute interrogative (a yes/no question) depending on the intonation pattern that a speaker produces. Patterns of usage also depend on dialect. For example, the intonation of absolute interrogatives typically is characterized as having a contour with a final rise and this may be the most common ending for absolute interrogatives in most dialects. This is true of descriptions of Peninsular (European) Spanish, Mexican Spanish, Chilean Spanish, and many other dialects. However, in some dialects, such as Venezuelan Spanish, absolute interrogatives have a contour with a final fall (a pattern that is more generally associated with declarative utterances and pronominal interrogative utterances). Most noteworthy, in Buenos Aires Spanish, both interrogative patterns are observed. This dissertation examines intonation patterns in the Spanish dialect spoken in Buenos Aires, Argentina, focusing on the two patterns associated with absolute interrogatives. It addresses two sets of questions. First, if a final fall contour is used for both interrogatives and declaratives, what other factors differentiate these utterances? The present study also explores other markers of the functional contrast between Spanish interrogatives and declaratives.