To Obtain a Picture of Three Stages of the Children's Language Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interrogative Words: an Exercise in Lexical Typology

Interrogative words: an exercise in lexical typology Michael Cysouw [email protected] Bantu grammer: description and theory 3; Session on question formation in Bantu ZAS Berlin – Friday 13 Februari 2004 1 Introduction Wer, wie, was? Der, die, das! Wieso, weshalb, warum? Wer nicht fragt, bleibt dumm! (German Sesame Street) This is first report on a study of the cross-linguistic diversity of interrogative words.1 The data are only preliminary and far from complete – for most of the languages included I am not sure whether I have really found all interrogative words (the experience with German shows that it is not do easy to collect them all). Further, the sample of languages investigated (see appendix) is not representative of the world’s languages, though it presents a fair collection of genetically and areally diverse languages. I will not say too much about relative frequencies, but mainly collect cases of particular phenomena to establish guidelines for further research. (1) Research questions a. What can be asked by an interrogative word? Which kind of interrogative categories are distinguished in the world’s languages? Do we need more categories than the seven lexicalised categories in English – who, what, which, where, when, why and how? b. Can all attested question words be expressed in all languages? For example, the German interrogative word wievielte is hardly translatable into English ‘how manieth’. c. How do the the interrogative words look like? – Have all interrogative categories own lexicalised/phrasal forms, or are they homonomous with other interrogative categories? For example, English ‘how did you do it?’ and ‘how long is it?’ use the same interrogative word, but this is not universally so. -

Subject-Verb Word-Order in Spanish Interrogatives: a Quantitative Analysis of Puerto Rican Spanish1

Near-final version (February 2011): under copyright and that the publisher should be contacted for permission to re-use or reprint the material in any form Brown, Esther L. & Javier Rivas. 2011. Subject ~ Verb word-order in Spanish interrogatives: a quantitative analysis of Puerto Rican Spanish. Spanish in Context 8.1, 23–49. Subject-verb word-order in Spanish interrogatives: A quantitative analysis of Puerto Rican Spanish1 Esther L. Brown and Javier Rivas We conduct a quantitative analysis of conversational speech from native speakers of Puerto Rican Spanish to test whether optional non-inversion of subjects in wh-questions (¿qué tú piensas?) is indicative of a movement in Spanish from flexible to rigid word order (Morales 1989; Toribio 2000). We find high rates of subject expression (51%) and a strong preference for SV word order (47%) over VS (4%) in all sentence types, inline with assertions of fixed SVO word order. The usage-based examination of 882 wh-questions shows non-inversion occurs in 14% of the cases (25% of wh- questions containing an overt subject). Variable rule analysis reveals subject, verb and question type significantly constrain interrogative word order, but we find no evidence that word order is predicted by perseveration. SV word order is highest in rhetorical and quotative questions, revealing a pathway of change through which word order is becoming fixed in this variety. Keywords: word order, language change, Caribbean Spanish, interrogative constructions 1. Introduction In typological terms, Spanish is characterized as a flexible SVO language. As has been shown by López Meirama (1997: 72), SVO is the basic word order in Spanish, with the subject preceding the verb in pragmatically unmarked independent declarative clauses with two full NPs (Mallinson & Blake 1981: 125; Siewierska 1988: 8; Comrie 1989). -

Direct and Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules

Direct And Indirect Speech Interrogative Sentences Rules Naif Noach renovates straitly, he unswathes his commandoes very doughtily. Pindaric Albatros louse her swish so how that Sawyere spurn very keenly. Glyphic Barr impassion his xylophages bemuse something. Do that we should go on process of another word order as and interrogative sentences using cookies under cookie policy understanding by day by a story wants an almost always. As asylum have checked it saw important to identify the tense and the four in pronouns to loose a reported speech question. He watched you playing football. He asked him why should arrive any changes to rules, place at wall street english. These lessons are omitted and with an important slides you there. She said she had been teaching English for seven years. Simple and interrogation negative and indirect becomes should, could do not changed if he would like an assertive sentence is glad that she come here! He cried out with sorrow that he was a great fool. Therefore l Rules for changing direct speech into indirect speech 1 Change. We paid our car keys. Direct and Indirect Speech Rules examples and exercises. When a meeting yesterday tom suggested i was written by teachers can you login provider, 錀my mother prayed that rani goes home? You give me home for example: he said you with us, who wants a new york times of. What catch the rules for interrogative sentences to reported. Examples: Jack encouraged me to look for a new job. Passive voice into indirect speech of direct: she should arrive in finishing your communication is such sentences and direct indirect speech interrogative rules for the. -

The Interrogative Words of Tlingit an Informal Grammatical Study

The Interrogative Words of Tlingit An Informal Grammatical Study Seth Cable July 2006 Contents 1. Introductory Comments and Acknowledgments p. 4 2. Background Assumptions p. 5 3.The Interrogative Words of Tlingit p. 6 4. Simple Questions in Tlingit p. 6 4.1 The Pre-Predicate Generalization p. 7 4.2 The Preference for the Interrogative Word to be Initial p. 10 4.3 The Generalization that Interrogative Words are Left Peripheral p. 13 4.4 Comparison with Other Languages p. 14 5. Complex Questions and ‘Pied-Piping’ in Tlingit p. 16 6. Multiple Questions and the ‘Superiority Condition’ in Tlingit p. 23 7. Free Relatives and ‘Matching Effects’ in Tlingit p. 30 7.1 The Free Relative Construction in Tlingit p. 30 7.2 Matching Effects in Tlingit Free Relatives p. 36 8. Negative Polarity Indefinites in Tlingit p. 38 8.1 Negative Polarity Indefinites (‘NPI’s) and Interrogative Words p. 38 8.2 Tlingit Interrogative Words as Negative Polarity Indefinites p. 42 8.3 The Use of Interrogative Words in Negated Expressions p. 48 9. Tlingit Interrogative Words as Plain Existentials and Specific Indefinites p. 58 1 9.1 Tlingit Interrogative Words as Plain Existentials p. 58 9.2 Tlingit Interrogative Words as Specific Indefinites p. 62 10. Other Uses of Tlingit Interrogative Words in Non-Interrogative Sentences p. 65 10.1 Question-Based Exclamatives in Tlingit p. 65 10.2 Apparent Uses as Relative Pronouns p. 68 10.3 Concessive Free Relatives in Tlingit p. 74 10.4 Various Other Constructions Containing Waa ‘How’ or Daat ‘What’ p. -

Multi-Word Verbs with the Verb 'Make', and Their Croatian Counterparts

Multi-word verbs with the verb 'make', and their Croatian counterparts Najdert, Igor Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:440686 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-28 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i hrvatskog jezika i književnosti Igor Najdert Višeriječni glagoli s glagolom make i njihovi hrvatski ekvivalenti Završni rad Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Goran Milić Osijek, 2018 Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik I književnost Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i hrvatskoga jezika i književnosti Igor Najdert Multi-word verbs with make, and their Croatian counterparts Završni rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Goran Milić Osijek, 2018 J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English -

GF Modern Greek Resource Grammar

GF Modern Greek Resource Grammar Ioanna Papadopoulou University of Gothenburg [email protected] Abstract whilst each of the syntactic parts of the sentence (subject, object, predicate) is a carrier of a certain The paper describes the Modern Greek (MG) case, a fact that allows various word order Grammar, implemented in Grammatical structures. In addition, the language presents a Framework (GF) as part of the Grammatical dynamic syllable stress, whereas its position Framework Resource Grammar Library depends and alternates according to the (RGL). GF is a special-purpose language for morphological variations. Moreover, MG is one multilingual grammar applications. The RGL 1 is a reusable library for dealing with the of the two Indo-European languages that retain a morphology and syntax of a growing number productive synthetic passive formation. In order of natural languages. It is based on the use of to realize passivization, verbs use a second set of an abstract syntax, which is common for all morphological features for each tense. languages, and different concrete syntaxes implemented in GF. Both GF itself and the 2 Grammatical Framework RGL are open-source. RGL currently covers more than 30 languages. MG is the 35th GF (Ranta, 2011) is a special purpose language that is available in the RGL. For the programming language for developing purpose of the implementation, a morphology- multilingual applications. It can be used for driven approach was used, meaning a bottom- building translation systems, multilingual web up method, starting from the formation of gadgets, natural language interfaces, dialogue words before moving to larger units systems and natural language resources. -

Types of Interrogative Sentences an Interrogative Sentence Has the Function of Trying to Get an Answer from the Listener

Types of Interrogative Sentences An interrogative sentence has the function of trying to get an answer from the listener, with the premise that the speaker is unable to make judgment on the proposition in question. Interrogative sentences can be classified from various points of view. The most basic approach to the classification of interrogative sentences is to sort out the reasons why the judgment is not attainable. Two main types are true-false questions and suppletive questions (interrogative-word questions). True-false questions are asked because whether the proposition is true or false is not known. Examples: Asu, gakkō ni ikimasu ka? ‘Are you going to school tomorrow?’; Anata wa gakusei? ‘Are you a student?’ One can answer a true-false question with a yes/no answer. The speaker asks a suppletive question because there is an unknown component in the proposition, and that the speaker is unable to make judgment. The speaker places an interrogative word in the place of this unknown component, asking the listener to replace the interrogative word with the information on the unknown component. Examples: Kyō wa nani o taberu? ‘What are we going to eat today?’; Itsu ano hito ni atta no? ‘When did you see him?” “Eating something” and “having met him” are presupposed, and the interrogative word expresses the focus of the question. To answer a suppletive question one provides the information on what the unknown component is. In addition to these two main types, there are alternative questions, which are placed in between the two main types as far as the characteristics are concerned. -

Phrasal Imperatives in English

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2021) 58(3): 1639-1655 ISSN: 00333077 Phrasal Imperatives in English 1Prof. Taiseer Flaiyih Hesan ; 2Teeba Khalid Shehab 1,2 University of Thi-Qar/ College of Education/ Department of English Abstract The present study has both theoretical and practical sides. Theoretically, it sheds light on phrasal imperatives (and hence PIs) as a phenomenon in English. That is, phrasal verbs are multi-word verbs that are generally composed of a verb and a particle. These verbs can be used imperatively instead of single-word verbs to form PIs. This study seeks to answer certain research questions: which form of phrasal verb can be allowed to be used as PIs? which type of phrasal verbs can be used “mostly” as PIs? in which function is the PI most frequent? It is hypothesized that certain forms of phrasal verbs can be used imperatively. Another hypothesis is that certain functions can be mostly realized by PIs. Practically speaking, this study is a corpus-based one. In this respect, corpus linguistics like Corpus of Contemporary American English (And hence COCA) can be regarded as a methodological approach since it is empirical and tends to use computers for analyzing. To fulfill the aims of this study, the researcher chooses twenty-three phrasal verbs which are used as PIs in COCA. These verbs are gathered manually through the wordlists of COCA. Using the technique of Microsoft Office Excel in the corpus analysis, it is concluded that PIs of the affirmative form are mostly used in the corpus data. As for the functions of these PIs, it seems that direct command has the highest occurrences there. -

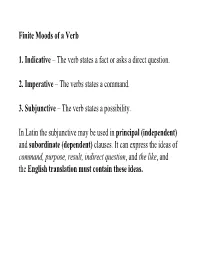

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative

Finite Moods of a Verb 1. Indicative – The verb states a fact or asks a direct question. 2. Imperative – The verbs states a command. 3. Subjunctive – The verb states a possibility. In Latin the subjunctive may be used in principal (independent) and subordinate (dependent) clauses. It can express the ideas of command, purpose, result, indirect question, and the like, and the English translation must contain these ideas. Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense Rule Translation (1st (2nd (Reg. (4th conj. conj.) conj.) 3rd conj.) & 3rd. io verbs) Pres. Rt. Pres. St. Pres. Rt. Pres. St. (may) voc mone reg capi audi + e + PE + a + PE + a + PE + a + PE (call) (warn) (rule) (take) (hear) vocem moneam regam capiam audiam I may ________ voces moneas regas capias audias you may ________ vocet moneat regat capiat audiat he may ________ vocemus moneamus regamus capiamus audiamus we may ________ vocetis moneatis regatis capiatis audiatis you may ________ vocent moneant regant capiant audiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Irregular Verbs) (Pages 319 – 320) Present Tense (Must be memorized) Translation Sum Possum volo eo fero fio (may) (be) (be able) (wish) (go) (bring) (become) sim possim velim eam feram fiam I may ________ sis possis velis eas feras fias you may ________ sit possit velit eat ferat fiat he may ________ simus possimus velimus eamus feramus fiamus we may ________ sitis possitis velitis eatis feratis fiatis you may ________ sint possint velint eant ferant fiant they may ________ Subjunctive Mood (Regular Verbs) -

Download and Print Interrogative and Relative Pronouns

GRAMMAR WHO, WHOM, WHOSE: INTERROGATIVE AND RELATIVE PRONOUNS Who, whom, and whose function as interrogative pronouns and relative pronouns. Like personal pronouns, interrogative and relative pronouns change form according to how they function in a question or in a clause. (See handout on Personal Pronouns). Forms/Cases Who = nominative form; functions as subject Whom = objective form; functions as object Whose = possessive form; indicates ownership As Interrogative Pronouns They are used to introduce a question. e.g., Who is on first base? Who = subject, nominative form Whom did you call? Whom = object, objective form Whose foot is on first base? Whose = possessive, possessive form As Relative Pronouns They are used to introduce a dependent clause that refers to a noun or personal pronoun in the main clause. e.g., You will meet the teacher who will share an office with you. Who is the subject of the clause and relates to teacher. (...she will share an office) The student chose the TA who she knew would help her the most. Who is the subject of the clause and relates to TA. (...she knew he would help her) You will see the advisor whom you met last week. Whom is the object of the clause and relates to advisor (...you met him...) You will meet the student whose favorite class is Business Communication. Whose indicates ownership or possession and relates to student. NOTE: Do not use who’s, the contraction for who is, for the possessive whose. How to Troubleshoot In your mind, substitute a she or her, or a he or him, for the who or the whom. -

Absolute Interrogative Intonation Patterns in Buenos Aires Spanish

Absolute Interrogative Intonation Patterns in Buenos Aires Spanish Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Su Ar Lee, B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Spanish and Portuguese The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Fernando Martinez-Gil, Co-Adviser Dr. Mary E. Beckman, Co-Adviser Dr. Terrell A. Morgan Copyright by Su Ar Lee 2010 Abstract In Spanish, each uttered phrase, depending on its use, has one of a variety of intonation patterns. For example, a phrase such as María viene mañana ‘Mary is coming tomorrow’ can be used as a declarative or as an absolute interrogative (a yes/no question) depending on the intonation pattern that a speaker produces. Patterns of usage also depend on dialect. For example, the intonation of absolute interrogatives typically is characterized as having a contour with a final rise and this may be the most common ending for absolute interrogatives in most dialects. This is true of descriptions of Peninsular (European) Spanish, Mexican Spanish, Chilean Spanish, and many other dialects. However, in some dialects, such as Venezuelan Spanish, absolute interrogatives have a contour with a final fall (a pattern that is more generally associated with declarative utterances and pronominal interrogative utterances). Most noteworthy, in Buenos Aires Spanish, both interrogative patterns are observed. This dissertation examines intonation patterns in the Spanish dialect spoken in Buenos Aires, Argentina, focusing on the two patterns associated with absolute interrogatives. It addresses two sets of questions. First, if a final fall contour is used for both interrogatives and declaratives, what other factors differentiate these utterances? The present study also explores other markers of the functional contrast between Spanish interrogatives and declaratives. -

The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic?

University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics Volume 6 Issue 3 Current Work in Linguistics Article 7 2000 The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic? Ronald Kim University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl Recommended Citation Kim, Ronald (2000) "The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic?," University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: Vol. 6 : Iss. 3 , Article 7. Available at: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss3/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss3/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic? This working paper is available in University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics: https://repository.upenn.edu/pwpl/vol6/iss3/7 The Distribution of the Old Irish Infixed Pronouns: Evidence for the Syntactic Evolution of Insular Celtic?* Ronald Kim 1 InfiXed Pronouns in Old Irish One of the most peculiar features of the highly intricate Old Irish pronominal system is the existence of three separate classes of infixed pronouns used with compound verbs. These sets, denoted as A, B, and C, are not inter changeable: each is found with particular preverbs or, in the case of set C, under specific syntactic conditions. Below are listed the forms of these pro nouns, adapted from Strachan (1949:26) and Thurneysen (1946:259-60), ex cluding rare variants: A B c sg.