Evidentiality and the Structure of Speech Acts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representation of Inflected Nouns in the Internal Lexicon

Memory & Cognition 1980, Vol. 8 (5), 415423 Represeritation of inflected nouns in the internal lexicon G. LUKATELA, B. GLIGORIJEVIC, and A. KOSTIC University ofBelgrade, Belgrade, Yugoslavia and M.T.TURVEY University ofConnecticut, Storrs, Connecticut 06268 and Haskins Laboratories, New Haven, Connecticut 06510 The lexical representation of Serbo-Croatian nouns was investigated in a lexical decision task. Because Serbo-Croatian nouns are declined, a noun may appear in one of several gram matical cases distinguished by the inflectional morpheme affixed to the base form. The gram matical cases occur with different frequencies, although some are visually and phonetically identical. When the frequencies of identical forms are compounded, the ordering of frequencies is not the same for masculine and feminine genders. These two genders are distinguished further by the fact that the base form for masculine nouns is an actual grammatical case, the nominative singular, whereas the base form for feminine nouns is an abstraction in that it cannot stand alone as an independent word. Exploiting these characteristics of the Serbo Croatian language, we contrasted three views of how a noun is represented: (1) the independent entries hypothesis, which assumes an independent representation for each grammatical case, reflecting its frequency of occurrence; (2) the derivational hypothesis, which assumes that only the base morpheme is stored, with the individual cases derived from separately stored inflec tional morphemes and rules for combination; and (3) the satellite-entries hypothesis, which assumes that all cases are individually represented, with the nominative singular functioning as the nucleus and the embodiment of the noun's frequency and around which the other cases cluster uniformly. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

Language in the USA

This page intentionally left blank Language in the USA This textbook provides a comprehensive survey of current language issues in the USA. Through a series of specially commissioned chapters by lead- ing scholars, it explores the nature of language variation in the United States and its social, historical, and political significance. Part 1, “American English,” explores the history and distinctiveness of American English, as well as looking at regional and social varieties, African American Vernacular English, and the Dictionary of American Regional English. Part 2, “Other language varieties,” looks at Creole and Native American languages, Spanish, American Sign Language, Asian American varieties, multilingualism, linguistic diversity, and English acquisition. Part 3, “The sociolinguistic situation,” includes chapters on attitudes to language, ideology and prejudice, language and education, adolescent language, slang, Hip Hop Nation Language, the language of cyberspace, doctor–patient communication, language and identity in liter- ature, and how language relates to gender and sexuality. It also explores recent issues such as the Ebonics controversy, the Bilingual Education debate, and the English-Only movement. Clear, accessible, and broad in its coverage, Language in the USA will be welcomed by students across the disciplines of English, Linguistics, Communication Studies, American Studies and Popular Culture, as well as anyone interested more generally in language and related issues. edward finegan is Professor of Linguistics and Law at the Uni- versity of Southern California. He has published articles in a variety of journals, and his previous books include Attitudes toward English Usage (1980), Sociolinguistic Perspectives on Register (co-edited with Douglas Biber, 1994), and Language: Its Structure and Use, 4th edn. -

Veridicality and Utterance Meaning

2011 Fifth IEEE International Conference on Semantic Computing Veridicality and utterance understanding Marie-Catherine de Marneffe, Christopher D. Manning and Christopher Potts Linguistics Department Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 {mcdm,manning,cgpotts}@stanford.edu Abstract—Natural language understanding depends heavily on making the requisite inferences. The inherent uncertainty of assessing veridicality – whether the speaker intends to convey that pragmatic inference suggests to us that veridicality judgments events mentioned are actual, non-actual, or uncertain. However, are not always categorical, and thus are better modeled as this property is little used in relation and event extraction systems, and the work that has been done has generally assumed distributions. We therefore treat veridicality as a distribution- that it can be captured by lexical semantic properties. Here, prediction task. We trained a maximum entropy classifier on we show that context and world knowledge play a significant our annotations to assign event veridicality distributions. Our role in shaping veridicality. We extend the FactBank corpus, features include not only lexical items like hedges, modals, which contains semantically driven veridicality annotations, with and negations, but also structural features and approximations pragmatically informed ones. Our annotations are more complex than the lexical assumption predicts but systematic enough to of world knowledge. The resulting model yields insights into be included in computational work on textual understanding. the complex pragmatic factors that shape readers’ veridicality They also indicate that veridicality judgments are not always judgments. categorical, and should therefore be modeled as distributions. We build a classifier to automatically assign event veridicality II. CORPUS ANNOTATION distributions based on our new annotations. -

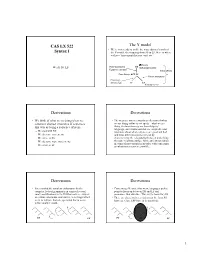

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras To cite this version: Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras. Romani Syntactic Typology. Yaron Matras; Anton Tenser. The Palgrave Handbook of Romani Language and Linguistics, Springer, pp.187-227, 2020, 978-3-030-28104- 5. 10.1007/978-3-030-28105-2_7. halshs-02965238 HAL Id: halshs-02965238 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02965238 Submitted on 13 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Romani syntactic typology Evangelia Adamou and Yaron Matras 1. State of the art This chapter presents an overview of the principal syntactic-typological features of Romani dialects. It draws on the discussion in Matras (2002, chapter 7) while taking into consideration more recent studies. In particular, we draw on the wealth of morpho- syntactic data that have since become available via the Romani Morpho-Syntax (RMS) database.1 The RMS data are based on responses to the Romani Morpho-Syntax questionnaire recorded from Romani speaking communities across Europe and beyond. We try to take into account a representative sample. We also take into consideration data from free-speech recordings available in the RMS database and the Pangloss Collection. -

(2012) Perspectival Discourse Referents for Indexicals* Maria

To appear in Proceedings of SULA 7 (2012) Perspectival discourse referents for indexicals* Maria Bittner Rutgers University 0. Introduction By definition, the reference of an indexical depends on the context of utterance. For ex- ample, what proposition is expressed by saying I am hungry depends on who says this and when. Since Kaplan (1978), context dependence has been analyzed in terms of two parameters: an utterance context, which determines the reference of indexicals, and a formally unrelated assignment function, which determines the reference of anaphors (rep- resented as variables). This STATIC VIEW of indexicals, as pure context dependence, is still widely accepted. With varying details, it is implemented by current theories of indexicali- ty not only in static frameworks, which ignore context change (e.g. Schlenker 2003, Anand and Nevins 2004), but also in the otherwise dynamic framework of DRT. In DRT, context change is only relevant for anaphors, which refer to current values of variables. In contrast, indexicals refer to static contextual anchors (see Kamp 1985, Zeevat 1999). This SEMI-STATIC VIEW reconstructs the traditional indexical-anaphor dichotomy in DRT. An alternative DYNAMIC VIEW of indexicality is implicit in the ‘commonplace ef- fect’ of Stalnaker (1978) and is formally explicated in Bittner (2007, 2011). The basic idea is that indexical reference is a species of discourse reference, just like anaphora. In particular, both varieties of discourse reference involve not only context dependence, but also context change. The act of speaking up focuses attention and thereby makes this very speech event available for discourse reference by indexicals. Mentioning something likewise focuses attention, making the mentioned entity available for subsequent dis- course reference by anaphors. -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Prosodic Focus∗

Prosodic Focus∗ Michael Wagner March 10, 2020 Abstract This chapter provides an introduction to the phenomenon of prosodic focus, as well as to the theory of Alternative Semantics. Alternative Semantics provides an insightful account of what prosodic focus means, and gives us a notation that can help with better characterizing focus-related phenomena and the terminology used to describe them. We can also translate theoretical ideas about focus and givenness into this notation to facilitate a comparison between frameworks. The discussion will partly be structured by an evaluation of the theories of Givenness, the theory of Relative Givenness, and Unalternative Semantics, but we will cover a range of other ideas and proposals in the process. The chapter concludes with a discussion of phonological issues, and of association with focus. Keywords: focus, givenness, topic, contrast, prominence, intonation, givenness, context, discourse Cite as: Wagner, Michael (2020). Prosodic Focus. In: Gutzmann, D., Matthewson, L., Meier, C., Rullmann, H., and Zimmermann, T. E., editors. The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Semantics. Wiley{Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781118788516.sem133 ∗Thanks to the audiences at the semantics colloquium in 2014 in Frankfurt, as well as the participants in classes taught at the DGFS Summer School in T¨ubingen2016, at McGill in the fall of 2016, at the Creteling Summer School in Rethymnos in the summer of 2018, and at the Summer School on Intonation and Word Order in Graz in the fall of 2018 (lectures published on OSF: Wagner, 2018). Thanks also for in-depth comments on an earlier version of this chapter by Dan Goodhue and Lisa Matthewson, and two reviewers; I am also indebted to several discussions of focus issues with Aron Hirsch, Bernhard Schwarz, and Ede Zimmermann (who frequently wanted coffee) over the years. -

Against Logical Form

Against logical form Zolta´n Gendler Szabo´ Conceptions of logical form are stranded between extremes. On one side are those who think the logical form of a sentence has little to do with logic; on the other, those who think it has little to do with the sentence. Most of us would prefer a conception that strikes a balance: logical form that is an objective feature of a sentence and captures its logical character. I will argue that we cannot get what we want. What are these extreme conceptions? In linguistics, logical form is typically con- ceived of as a level of representation where ambiguities have been resolved. According to one highly developed view—Chomsky’s minimalism—logical form is one of the outputs of the derivation of a sentence. The derivation begins with a set of lexical items and after initial mergers it splits into two: on one branch phonological operations are applied without semantic effect; on the other are semantic operations without phono- logical realization. At the end of the first branch is phonological form, the input to the articulatory–perceptual system; and at the end of the second is logical form, the input to the conceptual–intentional system.1 Thus conceived, logical form encompasses all and only information required for interpretation. But semantic and logical information do not fully overlap. The connectives “and” and “but” are surely not synonyms, but the difference in meaning probably does not concern logic. On the other hand, it is of utmost logical importance whether “finitely many” or “equinumerous” are logical constants even though it is hard to see how this information could be essential for their interpretation. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics.