The Parliament's Public Relations in Terms of Political Journalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sovietinės Represijos Prieš Lietuvos Kariuomenės Karininkus

SOVIETINĖS REPRESIJOS PRIEŠ LIETUVOS KARIUOMENĖS KARININKUS Ats. plk. Andrius Tekorius Generolo Jono Žemaičio Lietuvos karo akademija Anotacija. Straipsnyje atskleistos sovietinių represijų prieš Lietuvos kariuome- nės karininkus priežastys, pobūdis ir mastas, pateikti duomenys apie represuotus Lietuvos krašto apsaugos ministrus ir karininkus. Pagrindiniai žodžiai: sovietinė okupacija, Lietuvos kariuomenė, Lietuvos ka- riuomenės karininkai, sovietinės represijos, šnipinėjimas, represuoti Lietuvos kari- ninkai ir krašto apsaugos ministrai. ĮVADAS Sovietinės okupacijos metais represijas patyrė didžioji mūsų tautos dalis. Okupantų buvo suimti, kalinti ir ištremti tūkstančiai Lietuvos gy- ventojų. Sovietinių represijų neišvengė ir Lietuvos karininkija. Ji tapo vienu pirmųjų sovietinių okupantų taikinių. Lietuvos karininkų1 sovietinių represijų tema Lietuvos istoriografi- joje nėra nauja. Šią temą įvairiais aspektais yra nagrinėję ir tyrimų re- zultatus skelbę Arvydas Anušauskas, Teresė Birutė Burauskaitė, Jonas Dobrovolskas, Stasys Knezys, Aras Lukšas, Algirdas Markūnas, Antanas Martinionis, Jonas Rudokas, Vytautas Jasulaitis, Gintautas Surgailis, Ro- mualdas Svidinskas, Antanas Tyla, Vytautas Zabielskas, Dalius Žygelis ir kiti. Sovietiniuose kalėjimuose ir lageriuose (priverčiamojo darbo stovy- klose) patirti išgyvenimai aprašyti Lietuvos kariuomenės karininkų Vik- toro Ašmensko, Antano Martinionio, Juozo Palukaičio, Jono Petruičio 1 Šiame straipsnyje Lietuvos karininkai skirstomi į tikrosios tarnybos karininkus, tar- navusius Lietuvos kariuomenėje -

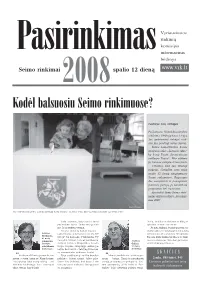

Rinkiminis Laikr 20.Pmd

Vyriausiosios rinkimø komisijos Pasirinkimas informacinis leidinys Seimo rinkimai 2008 spalio 12 dienà www.vrk.lt Kodël balsuosiu Seimo rinkimuose? Leidinys Tau, rinkëjau Po Lietuvos Nepriklausomybës atkûrimo 1990-øjø kovo 11-àjà, Jûs, gerbiamieji rinkëjai, rink- site jau penktàjá ðalies Seimà. Ðalies Konstitucijos 2-asis straipsnis sako: „Lietuvos valsty- bæ kuria Tauta. Suverenitetas priklauso Tautai“. Mes siûlome jà, Lietuvos valstybæ, ið tiesø kurti. Viliamës, kad Jûs, mielieji rinkëjai, iðreikðite savo valià spalio 12 dienà rengiamuose Seimo rinkimuose. Raginame Jus susipaþinti ir panagrinëti politiniø partijø, jø kandidatø programas bei nuostatas. Specialiai ðiems Seimo rinki- mams skirtas leidinys „Pasirinki- mas 2008“. ELTOS nuotr. Prie rinkimø balsadëþës susitiks skirtingø kartø atstovai. Jø balsai lems, kurie politikai pasidalys 141 vietà Seime. Tada supratau, kaip svarbu turëti Noriu, kad ðiuose rinkimuose bûtø at- pasirinkimo laisvæ. Dabar mes jà turi- spindëta ir mano nuomonë. me. Ir tai reikëtø vertinti. Jei mes, rinkëjai, bûsime pasyvûs, tu- Að savo mokiniø daþnai klausiu – rësime taikstytis su kitø sprendimu, kitø Faustas kam priklauso aukðèiausioji valdþia Lie- iðrinktais valdþios atstovais. Nesuprantu Meðkuotis, tuvoje? Jie man sako: Prezidentui, Vy- þmoniø, kurie keikia valdþià, nors rinki- 41 metø gimnazijos riausybei, Seimui. Tada að pasiûlau pa- Justinas muose nebalsuoja. Tikiu, kad galima pa- istorijos, þvelgti á Lietuvos Respublikos Konsti- Galinis, siekti teigiamø permainø. pilietiðkumo tucijà. 2-ajame straipsnyje aiðkiai pa- 21 metø mokytojas raðyta, kad Lietuvos valstybæ kuria Tau- studentas ta, suverenitetas priklauso Tautai. SKAIÈIUS: “Kai buvau 19 metø jaunuolis, tar- Taigi aukðèiausioji valdþia ðiandien “Manau, iðreikðti savo pilietinæ po- navau sovietø armijoje Kazachstane. priklauso bûtent mums, ðalies pilie- zicijà – bûtina. Planuoju pasiskaityti 2 mln. -

Tauta Ruošiasi Sukilti

Lietuvių Fronto Bičiulių Europos Lietuvių Fronto Bičiulių Valdyba Vyr. Taryba Prof. dr. Zenonas Ivinskis (Vokietija), pirmi 6441 So. Washtenaw Avenue Chicago, Ill. 60629 ninkas 53 Bonn Am Hof 34 Dr. Kazys Ambrozaitis, Chesterton, Indiana Germany Dr. Kajetonas J. Čeginskas (Švedija), sekre Dr. Zigmas Brinkis, Los Angeles, California torius J. Barasas (Vokietija), iždininkas Dr. Petras Kisielius, Cicero, Illinois Alina Grinienė (Vokietija), biuletenio redak torė Dr. Antanas Klimas, Ro chester, New York Kun. Bronius Liubinas (Vokietija), ELI vedėjas Pilypas Narutis, Chicago, Il linois Levas Prapuolenis, Chicago, Illinois Dr. Antanas Razma, Joliet, Illinois J. A. V. ir Kanados Lietuvių Fronto Bičiulių Antanas Sabalis, Woodhaven, Centro Valdyba New York Juozas Mikonis, pirmininkas Leonardas Valiukas, Los An 24526 Chardon Road geles, California Cleveland, Ohio 44143 Lietuvių Fronto Bičiulių Dr. Juozas Skrinska, vicepirmininkas vyr. tarybai priklauso ir Dr. Česlovas Kuras, vicepirmininkas Kanadai LPB kraštų pirmininkai: Europos — prof. Zenonas Vladas Palubinskas, sekretorius Ivinskis, Amerikos — Juo zas Mikonis, Kanados — Juozas Žilionis, iždininkas — Vytautas Aušrotas ir “Į Vytautas Petrulis, iždo sekretorius Laisvę” redaktorius Juozas Kojelis. Vincas Akelaitis, biuletenio redaktorius Metinė “Į Laisvę” žurnalo prenumerata Australijoje, JAV-se ir Kanadoje — 5.00 doleriai, visur kitur — 3.00 doleriai; atskiro numerio kaina — 2.00 doleriai. Užsakymus ir prenumeratos mokestį siųsti administracijos adresu: Mr. Aleksas Kulnys 1510 East Merced -

Vilniaus Universitetas

VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETAS Audron ÷ Veilentien ÷ LIETUVOS RESPUBLIKOS SEIM Ų ĮTAKA UŽSIENIO POLITIKAI 1920–1927 METAIS Daktaro disertacija Humanitariniai mokslai, istorija (05 H) Vilnius, 2010 Disertacija ginama eksternu Mokslinis konsultantas: prof. dr. Zenonas Butkus (Vilniaus universitetas, humanitariniai mokslai, istorija – 05 H) 2 TURINYS ĮVADAS. 4 1. STEIGIAMOJO SEIMO IND öLIS Į LIETUVOS TARPTAUTIN öS PAD öTIES STABILIZACIJ Ą: 18 1.1. Parlamento kompetencija ir Lietuvos tarptautinio pripažinimo problemos 18 1.2. Seimo įtaka Taikos sutarties su Soviet ų Rusija rengimui ir jos ratifikavimas 41 1.3. Seimas ir santykiai su Lenkija: 59 1.3.1. Nutarimai Vilniaus klausimu. 59 1.3.2. Derybos su Lenkija ir Vilniaus lenk ų atstovais. 79 1.3.3. Lietuvos delegacijos veikla Briuselyje. 93 1.3.4. Hymanso projekt ų vertinimai. 114 1.4. Bendradarbiavimas su Baltijos šali ų parlamentais. 131 2. I SEIMO FRAKCIJ Ų NESUTARIM Ų POVEIKIS UŽSIENIO POLITIKAI. 145 3. II SEIMO DARBAI UŽSIENIO POLITIKOS SRITYJE : 161 3.1. Tarptautin ÷s orientacijos pakeitimas. 161 3.2. Klaip ÷dos krašto konvencijos ir integracijos vertinimai. 185 3.3. Santykiai su Didži ąja Britanija ir Baltijos šalimis. 202 3.4. Nes ÷kming ų deryb ų su Vatikanu ir Lenkija panaudojimas rinkimin ÷se kovose 214 4. III SEIMAS IR DIPLOMATIN öS IZOLIACIJOS PROBLEMOS: 230 4.1. Užsienio politikos klausimai Seime. 230 4.2. Užsienio reikal ų komisijos ind ÷lis rengiant Nepuolimo sutart į su SSRS ir jos ratifikavimas. 246 5. UŽSIENIO REIKAL Ų MINISTERIJOS BIUDŽETO FORMAVIMAS 262 IŠVADOS. 281 ŠALTINI Ų IR LITERAT ŪROS S ĄRAŠAS. 285 3 Į V A D A S Valstybingumo ir parlamentarizmo siekius išreišk ÷ beveik vis ų XIX a. -

(Pirmadienis) Rokiškio Krašto Muziejus Tyzenhauzų G

AUKŠTAITIJOS REGIONO PROGRAMA. 2017 metai BIRŽELIO 19–LIEPOS 30 D. Birželio 19 d. (pirmadienis) Rokiškio krašto muziejus Tyzenhauzų g. 5, Rokiškis, tel. (8 458) 31 512 16.00 Parodos „Kraštiečiai Lietuvos valstybės kūrėjai“ pristatymas. Dabartiniame Rokiškio rajone yra gimęs 1918 m. vasario 16-osios Nepriklausomybės Akto signataras, kunigas, ministras pirmininkas Vladas Mironas, ministrai pirmininkai Juozas Tubelis ir Antanas Tumėnas bei žymiausias Lietuvos Respublikos teisininkas, vienas iš Lietuvos nepriklausomybės atkūrimo sąjūdžio ideologų prof. Mykolas Romeris. Renginys nemokamas. Paroda „Kraštiečiai Lietuvos valstybės kūrėjai“ eksponuojama: Birželio 20–26 d. Panemunėlio universaliame daugiafunkciniame centre (Stoties g. 16, Panemunėlio sen., Rokiškio r.) Birželio 27 d.–liepos 4 d. Rokiškio rajono savivaldybės J. Keliuočio viešosios bibliotekos Pandėlio miesto filiale (Panemunio g. 23, Pandėlys, Rokiškio r. sav.) Liepos 4–10 d. Kriaunų istorijos muziejuje (Kriaunos, Rokiškio r.) Liepos 11–18 d. Rokiškio rajono savivaldybės J. Keliuočio viešosios bibliotekos Ragelių filiale (Ragelių g. 11, Ragelių k., Rokiškio r. sav.). Birželio 19–21 d. Lietuvos nacionalinė Martyno Mažvydo biblioteka Gedimino pr. 51, Vilnius, tel. (8 5) 249 7028. Tarptautinė paroda „Nepriklausomų valstybių – Lietuvos ir Latvijos – kūrėjai Mintaujos gimnazijoje“. Šiaulių „Aušros“ muziejaus ir G. Eliaso Jelgavos istorijos ir meno muziejaus (Latvija) parodoje pristatomi dviejų tautų (Lietuvos ir Latvijos) atstovai, kurie mokėsi Mintaujos gimnazijoje ir prisidėjo prie nepriklausomų valstybių kūrimo. Tai – Latvijos Respublikos prezidentai Janis Čakstė ir Albertas Kviesis, Lietuvos Respublikos Prezidentas Antanas Smetona, Lietuvos ministrai pirmininkai Mykolas Sleževičius, Vytautas Petrulis, Juozas Tūbelis, Vladas Mironas ir daugelis kitų asmenybių, darbu ir kūryba prisidėjusių prie abiejų šalių suklestėjimo. Paroda parengta lietuvių ir latvių kalbomis. Parodos lankymas nemokamas. Birželio 19–23 d. Kauno technologijos universiteto muziejus K. -

Vilniaus Pedagoginis Universitetas Istorijos Fakultetas Lietuvos Istorijos Katedra Ii Lietuvos Seimas 1923

VILNIAUS PEDAGOGINIS UNIVERSITETAS ISTORIJOS FAKULTETAS LIETUVOS ISTORIJOS KATEDRA Raimundas Trinkūnas Lietuvos lokalinės istorijos specialybės II kurso magistrantas II LIETUVOS SEIMAS 1923 -1926 M. Magistro darbas Magistrantas ___________________ (parašas) Raimundas Trinkūnas Leidžiama ginti: Darbo vadovas __________________ (parašas) IF Dekanas __________________ Prof. habl. dr. Liudas Truska (parašas) Doc. dr. Eugenijus Jovaiša darbo įteikimo data: ______________ Registracijos numeris: _____________ Vilnius, 2007 PATVIRTINIMAS APIE ATLIKTO DARBO SAVARANKIŠKUMĄ Patvirtinu, kad įteikiamas magistro darbas „II Lietuvos Seimas 1923 – 1926 m.“: 1. Autoriaus atliktas savarankiškai, jame nėra pateikta kitų autorių medžiagos kaip savos, nenurodant tikrojo šaltinio. 2. Nebuvo to paties autoriaus pristatytas ir gintas kitoje mokymo įstaigoje Lietuvoje ar užsienyje. 3. Nepateikia nuorodų į kitus darbus, jeigu jų medžiaga nėra naudota darbe. 4. Pateikia visą naudotos literatūros sąrašą. Raimundas_Trinkūnas___ _______________ (studento vardas, pavardė) (parašas) 2 TURINYS ĮVADAS ................................................................................................................. 4 I. POLITINĖ SITUACIJA II SEIMO RINKIMŲ IŠVAKARĖSE ............ 10 II. II. SEIMO RINKIMAI: 1. Rinkimai ............................................................................................ 13 2. Rinkimų rezultatai – balsų pasiskirstymas ...................................... 19 3. Kiekybinė ir kokybinė naujojo Seimo sudėtis ................................. -

Dangiras Mačiulis and Darius Staliūnas

STUDIEN zur Ostmitteleuropaforschung 32 Dangiras Mačiulis and Darius Staliūnas Lithuanian Nationalism and the Vilnius Question, 1883-1940 Dangiras Mačiulis and Darius Staliūnas, Lithuanian Nationalism and the Vilnius Question, 1883-1940 STUDIEN ZUR OSTMITTELEUROPAFORSCHUNG Herausgegeben vom Herder-Institut für historische Ostmitteleuropaforschung – Institut der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft 32 Dangiras Mačiulis and Darius Staliūnas Lithuanian Nationalism and the Vilnius Question, 1883-1940 VERLAG HERDER-INSTITUT · MARBURG · 2015 Bibliografi sche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografi e; detaillierte bibliografi sche Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar Diese Publikation wurde einem anonymisierten Peer-Review-Verfahren unterzogen. This publication has undergone the process of anonymous, international peer review. © 2015 by Herder-Institut für historische Ostmitteleuropaforschung – Institut der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft, 35037 Marburg, Gisonenweg 5-7 Printed in Germany Alle Rechte vorbehalten Satz: Herder-Institut für historische Ostmitteleuropaforschung – Institut der Leibniz-Gemeinschaft, 35037 Marburg Druck: KN Digital Printforce GmbH, Ferdinand-Jühlke-Straße 7, 99095 Erfurt Umschlagbilder: links: Cover of the journal „Trimitas“ (Trumpet) of the Riflemen’s Union of Lithuania. Trimitas, 1930, no. 41 rechts: The fi rst watch of Lithuanian soldiers at the tower of Gediminas Castle. 10 28 1939. LNM ISBN 978-3-87969-401-3 Contents Introduction -

1. Fabrikas Kaip Moderniosios Architektūros Pirmavaizdis

UDK 72(474.5)(091) Dr-166 Knygos leidimą finansavo Lietuvos mokslo taryba pagal Nacionalinę lituanistikos plėtros 2009–2015 metų programą (Sutarties Nr. LIT-9-39) Knyga leidžiama bendradarbiaujant su Vilniaus universitetu RECENZENTAI Dr. Dangiras Mačiulis Doc. dr. Vaidas Petrulis KALBOS REDAKTORIUS Nerijus Šepetys VERTĖJAS Į ANGLŲ K. Jurij Dobriakov ANGLŲ K. REDAKTORIUS Joseph Everatt VAIZDŲ REDAKTORĖ Jurga Dovydėnaitė KNYGOS DIZAINERIS Linas Gliaudelis MAKETUOTOJA Eglė Jurkūnaitė © Marija Drėmaitė, 2016 © Leidykla LAPAS, 2016 www.leidyklalapas.lt ISBN 978-609-95484-4-9 TURINYS PRATARMĖ 11 ĮVADAS. PRAMONĖ IR MODERNIZMAS 15 1. FABRIKAS KAIP MODERNIOSIOS ARCHITEKTŪROS PIRMAVAIZDIS 31 Technologinė modernizacija 31 Našumo ir valdymo modernizacija 35 Estetinė problema: utilitarumas vs dekoras 38 Racionalusis fabrikas kaip modernybės simbolis 42 2. LIETUVOS INDUSTRIALIZACIJA IR INDUSTRIALIZUOTOJAI 49 Rusijos imperijos palikimas 51 Nauji iššūkiai – Lietuvos pramonės kryptys 57 Profesinė specializacija: kas ir kaip projektuoja modernią įmonę 65 Techninė kultūra ir mokslinė vadyba 70 Naujų įmonių statyba ir reglamentavimas 75 3. „MAISTO IR DAR MAISTO“: ŽEMĖS ŪKIO PRAMONĖS PASTATAI 81 Reikia modernizuoti žemės ūkio pramonę 83 „Elevatorius būtina statyti tuojaus“: eksportinės agropramonės organizavimas 86 Ponas Lietūkis plečiasi 92 Pienocentras – per pienines modernizuojama Lietuva 102 „Sukiaulinkime Lietuvą“: skerdyklos, šaldyklos ir bekonai 131 „Cukrus duoda jėgos!“: bendrovė Lietuvos cukrus ir cukraus fabrikai 152 4. PRAMONĖS MODERNĖJIMAS – TARP -

Lietuvos Metrastis

LIETUVOS ISTORIJOS INSTITUTAS LIETUVOS ISTORIJOS METRASTIS 1997 metai Vilnius 1998 / /"\, INSTITUTE O~F LITHUANIAN HISTORY THE YEAR-BOOK OF LITHUANIAN HISTORY 1997 VILNIUS 1998 INSTITUT FUR LITAUISCHE GESCHICHTE JAHRBUCH FUR LITAUISCHE GESCHICHTE 1997 VILNIUS 1998 UDK 947.45 Li 237 Redakcine komisija Vytautas MERKYS (pirm.), Antanas TYLA (pirm. pavaquotojas), Vaeys MILIUS, Gediminas RUDIS, Rita STRAZDtJNAITE (sekretore), Gintautas ZABIELA Redakcin6s komisijos adresas: Kraziu g. 5, 2001 Vilnius I§leista Lietuvos jstorijos instituto uzsakymu ISSN 0202-3342 ISBN 8896-34-025-X ISSN 0202-3342 LIETUVOS ISTORIJOS METRASTIS.1997 METAI. VILNIUS,1998 THE YEAR-BOOK OF LITHUANIAN HISTORY.1997. VILNIUS,1998 RECENZIJOS, APZVALGOS, AINOTACIJOS Eugenijus S v e t i k a s. Apkalai su Birdies simboliu Lietuvoje kontrreformaci- jos laikotarpio pradzioje. -Lituanistica. -1997. -Nr.1(29). -P. 28-34; Kap§e- lip apkalai su litito simboliu Lietuvoje XV a. antrojoje puseje. - Lituanistica. - 1997. -Nr. 2(30). -P. 20-29. Eugenijaus Svetiko straipsniai apie senkapiuose rastus dirzu ir piniginiu apka- lus - aktualtis, turiningi, ta6iau kai kurie juose i5d6styti vertinimai kelia abejoniu. Pameginsime jas i§sakyti. Dirzu apkaluose pavaizduotoje §irdziu eiluteje autorius link?s izvelgti penkiu §ventu Jezaus Kristaus Zaizdu motyva, sieja juos su j6zuitu kontrreformacijos pra- dzioje skleistu Dievo Ktino kultu, su religingumo skatinimu skleidziant smulkius daiktus su kulto esm? vaizduojan6iu simboliu. Pirmiausia pastebesime, kad dirzas nera smulkus daiktas. Be to, brangus, ypa6 gamintas mieste. Abejotina ir tai, kad visi apkalai yra XVI a. VIII-IX de§imtme6io. Pats autorius pasteb6jo, kad Alytaus kapinyno kape Nr. 526 ir Rum§i§kiu kapinyno kape Nr. 184 rasta po tris Aleksan- dro Jogailai6io denarus. -

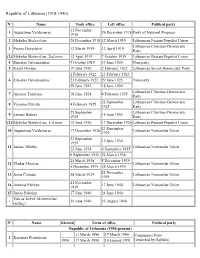

List of Prime Ministers of Lithuania

Republic of Lithuania (1918-1940) Nº Name Took office Left office Political party 11 November 1 Augustinas Voldemaras 26 December 1918 Party of National Progress 1918 2 Mykolas Sleževičius 26 December 1918 12 March 1919 Lithuanian Peasant Populist Union Lithuanian Christian-Democratic 3 Pranas Dovydaitis 12 March 1919 12 April 1919 Party (2) Mykolas Sleževičius, 2nd term 12 April 1919 7 October 1919 Lithuanian Peasant Populist Union 4 Ernestas Galvanauskas 7 October 1919 19 June 1920 Non-party 5 Kazys Grinius 19 June 1920 2 February 1922 Lithuanian Social-Democratic Party 2 February 1922 23 February 1923 6 Ernestas Galvanauskas 23 February 1923 29 June 1923 Non-party 29 June 1923 18 June 1924 Lithuanian Christian-Democratic 7 Antanas Tumėnas 18 June 1924 4 February 1925 Party 25 September Lithuanian Christian-Democratic 8 Vytautas Petrulis 4 February 1925 1925 Party 25 September Lithuanian Christian-Democratic 9 Leonas Bistras 15 June 1926 1925 Party (2) Mykolas Sleževičius, 3rd term 15 June 1926 17 December 1926 Lithuanian Peasant Populist Union 23 September 10 Augustinas Voldemaras 17 December 1926 Lithuanian Nationalist Union 1929 23 September 12 June 1934 1929 11 Juozas Tūbelis Lithuanian Nationalist Union 12 June 1934 6 September 1935 6 September 1935 24 March 1938 24 March 1938 5 December 1939 12 Vladas Mironas Lithuanian Nationalist Union 5 December 1939 28 March 1939 21 November 13 Jonas Černius 28 March 1939 Lithuanian Nationalist Union 1939 21 November 14 Antanas Merkys 17 June 1940 Lithuanian Nationalist Union 1939 15 Justas -

P. Dovydaitis Ir III Lietuvos Vyriausybė 1919 M. Kovo 12–1919 M

https://doi.org/10.24101/logos.2019.48 Gauta 2019 07 18 VAIDOTAS A. VAIčAITIS Vilniaus universitetas, Lietuva Vilnius university, Lithuania P. DOVYDAITIS IR III LIETuVOS VYRIAuSYbė 1919 M. KOVO 12–1919 M. bALAnDŽIO 12 D. Pranas Dovydaitis and the 3rd Lithuanian Government (March 12, 1919–April 12, 1919) SuMMARY This article analyzes the personality of the interwar Lithuanian social activist prof. Pranas Dovydaitis. The first paragraphs of the article show the conditions under which his personality was formed and the domestic and international conditions that pushed him to the center of most important political events in Lithuania (still under the czarist regime) in the second decade of twentieth century. The second part of the article analyzes the domestic and international conditions under which the third Cabinet of Ministers in 1919 was formed, which was briefly led by Pranas Dovydaitis as Prime Minister. The article also focuses on the composition and spheres of activity of the Third Lithuanian Cabinet of Ministers, as well as showing the political conditions that led to its resignation after a month of work. The article concludes with a summary and a note that prof. Dovy- daitis and four other members of his Government were arrested and expelled from Lithuania by the Soviet authorities in 1940–1941. Dovydaitis himself was shot in the nKVD prison in 1942 in Sverdlovsk, Russia. SAnTRAuKA Šiame straipsnyje atskleidžiama vieno žymiausių tarpukario Lietuvos visuomenės veikėjų prof. Prano Do- vydaičio asmenybė. Pirmose straipsnio dalyse parodoma, kokiomis sąlygomis formavosi jo asmenybė ir kokios vidaus bei tarptautinės aplinkybės lėmė, kad XX a. antrajame dešimtmetyje jis atsidūrė svarbiausių politinių įvykių, vykusių Lietuvos teritorijoje, sūkuryje. -

Lietuvos Bankas 1922-1943 Metais

Vladas TERLECKAS LIETUVOS BANKAS 1922-1943 METAIS Vladas TERLECKAS LIETUVOS BANKAS 1922-1943 METAIS Kūrimo ir veiklos studija Vilnius 1997 UDK 336.7(474.5)(091) Te-115 Recenzavo dr. G. Nausėda ir V. Andriuškevičius Redagavo E. Vilkauskienė ISBN 9986-651-15-8 © V. Terleckas, 1997 ISBN 978-609-8204-04-9 (online) TURINYS ĮŽA NG A ................................................................................4 I dalis LIETUVOS BANKO ISTORIJA........................................ 7 1. Lietuvos banko įsteigimas................................................. 9 1.1. Įstatymo projektai...........................................................9 1.2. Diskusijos Seime dėl įstatymo..................................... 12 1.3. Banko įsteigimas........................................................... 18 2. Banko statusas ir organizaciniai pagrindai....................27 3. Banko įstatymo, struktūros ir vadovų pasikeitimai......46 4. Dukartinis banko likvidavimas....................................... 63 4.1. Inkorporavimas į SSRS valstybinį banką...................63 4.2. Atkūrimas ir pakartotinis likvidavimas....................... 73 4.3. Lito ir Lietuvos banko kūrėjų likimai......................... 84 II dalis LIETUVOS BANKO VEIKLOS BRUOŽAI.................. 93 1. Veiklos barai..................................................................... 94 2. Kreditavimo organizavimas............................................ 99 3. Kredito politika: tikslai, priemonės ir pokyčiai........... 109 3.1. Kredito politikos formavimasis................................