Dangiras Mačiulis and Darius Staliūnas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antanas Smetona Gimė 1874 M

Antanas Smetona gimė 1874 m. rugpjūčio 10 d. Užulėnio kaime (dab. Ukmergės r.) gausioje neturtingų valstiečių šeimoje. Mokėsi Tau- jėnų pradinėje mokykloje, privačiai – Ukmergėje ir Liepojoje, 1893 m. baigė Palangos progimnaziją. 1896 m. buvo pašalintas iš Mintaujos (dab. Jelgava, Latvija) gimnazijos, nes kartu su kitais lietuviais nepa- kluso reikalavimui, kad katalikai kasdienę maldą mokykloje skaitytų rusiškai. 1897 m. eksternu baigė Peterburgo 9-ąją gimnaziją. Studijavo Peterburgo universiteto Teisės fakultete, priklausė slaptai lietuvių stu- dentų draugijai. Gavęs teisininko diplomą, A. Smetona 1902 m. atvyko į Vilnių, dir- bo advokato padėjėju, vėliau – banke. Jis greit iškilo kaip vienas akty- viausių lietuvių tautinio judėjimo dalyvių. Priklausė Lietuvių demok- ratų partijai. Buvo 1905 m. gruodžio 4–5 d. vykusio Didžiojo Vilniaus Seimo narys, pirmininkavo jo posėdžiui, kuriame svarstytas Lietuvos autonomijos klausimas. A. Smetona dalyvavo daugelio lietuviškų vi- suomeninių, kultūros, švietimo organizacijų – „Aušros“, „Ryto“, „Rū- ANTANAS SMETONA tos“, Lietuvių mokslo ir Lietuvių dailės draugijų – veikloje. Talkino 1874 08 10–1944 01 09 rengiant lietuviškus leidinius: redagavo laikraščius „Vilniaus žinios“, „Lietuvos ūkininkas“, „Viltis“, 1914–1924 m. – žurnalą „Vairas“, paren- gė informacinių ir publicistinių straipsnių tautinės veiklos klausimais. Smetonų šeimos butas Vilniuje buvo lietuvių inteligentų susibūrimų ir diskusijų vieta. Pirmojo pasaulinio karo metais Vilniuje pradėjusi veikti Lietuvių draugija nukentėjusiesiems dėl karo šelpti greit tapo ne tik labdaros organizacija, bet ir lietuvių politinės veiklos centru. Nuo pat įkūrimo organizacijoje dirbęs, o 1914 m. pabaigoje jos Centro komiteto vado- vu tapęs A. Smetona rūpinosi, kad kraštą okupavusios Vokietijos val- džios sprendimai kuo mažiau alintų Lietuvos žmones. 1916 m. kartu su Steponu Kairiu ir Jurgiu Šauliu dalyvavo Trečiajame pavergtųjų tautų kongrese. -

Vincas Kudirka, Martynas Jankus, Jonas Šliūpas and the Making of Modern Lithuania Charles C

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Summer 2013 Lithuanians in the Shadow of Three Eagles: Vincas Kudirka, Martynas Jankus, Jonas Šliūpas and the Making of Modern Lithuania Charles C. Perrin Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Perrin, Charles C., "Lithuanians in the Shadow of Three Eagles: Vincas Kudirka, Martynas Jankus, Jonas Šliūpas and the Making of Modern Lithuania." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LITHUANIANS IN THE SHADOW OF THREE EAGLES: VINCAS KUDIRKA, MARTYNAS JANKUS, JONAS ŠLIŪPAS AND THE MAKING OF MODERN LITHUANIA by CHARLES PERRIN Under the Direction of Hugh Hudson ABSTRACT The Lithuanian national movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was an international phenomenon involving Lithuanian communities in three countries: Russia, Germany and the United States. To capture the international dimension of the Lithuanian na- tional movement this study offers biographies of three activists in the movement, each of whom spent a significant amount of time living in one of -

Lithuanian Dialectology Profiles: Problems and Findings”, Aims to Demonstrate a Wide Range of Studies Within Lithuanian Dialectology

3 Approved for publishing by the Scientific Council of the Institute of the Lithuanian Language Decree Protocol No. MT-50, dated 30 December 2020 Editorial Board: Danguolė Mikulėnienė (Editor-in-Chief) Lietuvių kalbos institutas Ana Stafecka LU Latviešu valodas institūts Miroslaw Jankowiak Akademie věd České republiky Edmundas Trumpa Latvijas universitāte Ilja Lemeškin Univerzita Karlova Special issue editor Violeta Meiliūnaitė Reviewers: Dalia Pakalniškienė Klaipėdos universitetas Liene Markus–Narvila Latvijas universitāte The bibliographic information about this publication is available in the National Bibliographic Data Bank (NBDB) of the Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania ISBN 978-609-411-279-9 DOI doi.org/10.35321/e-pub.8.problems-and-findings © Institute of the Lithuanian Language, 2020 © Violeta Meiliūnaitė, compilation, 2020 © Contributing authors, 2020 Contents PREFACE ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 6 DANGUOLĖ MIKULĖNIENĖ ISSUES OF PERIODIZATION: DIALECTOLOGICAL THOUGHT, METHODOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT AND IDEOLOGICAL TURNS ------------------------------------ 8 VIOLETA MEILIŪNAITĖ. STABILITY AND DYNAMICS OF (LITHUANIAN) DIALECTAL NETWORK 38 JURGITA JAROSLAVIENĖ.METHODOLOGICAL DIVERSITY AND COMPLEXITY IN COMPARATIVE EXPERIMENTAL SOUND RESEARCH --------------------------------------------------------------------- 50 RIMA BAKŠIENĖ.INSTRUMENTAL RESEARCH INTO THE QUALITATIVE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE VOCALISM VARIANTS IN THE SUBDIALECT OF ŠAKIAI ----------------------------------------- -

Rehabilitation and Extension of Water Supply and Sewage Collection Systems in Vilnius (Stages 1 and 2)

Summary sheet of measure No 2000/LT/16/P/PE/001: Measure title Rehabilitation and Extension of Water Supply and Sewage Collection Systems in Vilnius (Stages 1 and 2) Authority responsible for implementation Municipality of Vilnius City, Gedimino av. 9,Vilnius, Lithuania Mayor of Vilnius, Mr Roland Paksas Email [email protected] Final beneficiary SP UAB Vilniaus Vandenys Dominikonu st 11,Vilnius, Lithuania Mr. B. Meizutavicius, Director General E.mail [email protected] Description Vilnius is the capital of Lithuania with a population of 580,000. The main drinking water and sewage networks date from the start of the 20th century and are in need of immediate repair. The expansion of the drinking water supply networks, as well as replacement of the worn out pipelines and the construction of iron removal plants (within separate complementary projects) will contribute to compliance with the EU standards for drinking water by reducing the iron content from 0.25-1.2 to 0.05mg/l. Also, some 99 percent of the Vilnius inhabitants and industries will be connected to the water supply networks. It should be noted that this is the first stage of a long term plan, for which the feasibility work has already been completed, which will result in full compliance with both water quality and waste water Directives. Component 1 Rehabilitation of a total of approximately 80km of water mains in the districts of Antakalnis, Baltupiai, Fabijoniškes, Justiniskes, Kirtimai, Lazdynai, Paneriai, Pasilaiciai, Virsuliskes, Zirmunai and the Old Town by relining of approximately 73 km of pipes ranging from less than 200mm to 1000mm diameter and replacement of some 7kms of pipes are in the utility corridors Component 2 Extension of the water supply and sewerage networks to serve the outlying areas of Gineitiskes, Traku Voke, Tarande, Bajorai, Balsiai, Kairenai, Naujoji Vilnia and Riese. -

To View Online Click Here

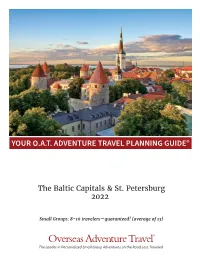

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® The Baltic Capitals & St. Petersburg 2022 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Enhanced! The Baltic Capitals & St. Petersburg itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: What I love about the little town of Harmi, Estonia, is that it has a lot of heart. Its residents came together to save their local school, and now it’s a thriving hub for community events. Harmi is a new partner of our Grand Circle Foundation, and you’ll live a Day in the Life here, visiting the school and a family farm, and sharing a farm-to-table lunch with our hosts. I love the outdoors and I love art, so my walk in the woods with O.A.T. Trip Experience Leader Inese turned into something extraordinary when she led me along the path called the “Witches Hill” in Lithuania. It’s populated by 80 wooden sculptures of witches, faeries, and spirits that derive from old pagan beliefs. You’ll go there, too (and I bet you’ll be as surprised as I was to learn how prevalent those pagan practices still are.) I was also surprised—and saddened—to learn how terribly the Baltic people were persecuted during the Soviet era. -

An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church Under Communism Kathryn Burns Union College - Schenectady, NY

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 More Catholic than the Pope: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism Kathryn Burns Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the European History Commons Recommended Citation Burns, Kathryn, "More Catholic than the Pope: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism" (2013). Honors Theses. 638. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/638 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “More Catholic than the Pope”: An Analysis of Polish Devotion to the Catholic Church under Communism By Kathryn Burns ******************** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of History UNION COLLEGE June 2013 Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………..........................................1 Chapter I. The Roman Catholic Church‟s Influence in Poland Prior to World War II…………………………………………………………………………………………………...4 Chapter II. World War II and the Rise of Communism……………….........................................38 Chapter III. The Decline and Demise of Communist Power……………….. …………………..63 Chapter IV. Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….76 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..78 ii Abstract Poland is home to arguably the most loyal and devout Catholics in Europe. A brief examination of the country‟s history indicates that Polish society has been subjected to a variety of politically, religiously, and socially oppressive forces that have continually tested the strength of allegiance to the Catholic Church. -

EXPERIENCE of VILNIUS DISTRICT HEATING COMPANY Producer of Heat Operator of District Customer Care for the Heating Network Heat and Hot Water Services

EXPERIENCE OF VILNIUS DISTRICT HEATING COMPANY Producer of heat Operator of district Customer care for the heating network heat and hot water services The Company operates in The Company owns and The Company supplies heat competitive market and supplies operates district heating and hot water for the end heat and electricity from network in Vilnius. We provide customer. combined heat and power plant. peak load and reserve capacity to ensure the quality of service for final customer. Key facts Established in 1958 Vilnius Infrastructure and capacity: District heating substations, Revenues of 131m EUR units Total assets of 139m EUR The company is the largest 25% 741 Length of the network, km supplier of heat and hot water 26% in Lithuania 7 218 Connected buildings, units Šiauliai Panevėžys 33% Telšiai 483 752 Annual heat supply, Klaipėda 2 752 Verkiai 44 018 60 445 GWh Vilnius 146 254 851 68 548 Utena Santariškės 217 26% Jeruzalė Baltupiai Antakalnis 1 436 Pašilaičiai Fabijoniškės Tauragė Heat production Justiniškės 68 548 Šeškinė 1 751 Žirmūnai 504 (by own sources), GWh Pilaitė Viršuliškės Šnipiškės Žvėrynas Naujoji Vilnia 2 916 Karoliniškės Kaunas Senamiestis 209 066 Naujamiestis 598 Grigiškės Rasos 31% Lazdynai Marijampolė Vilnius Number of clients Vilkpėdė 230 212 781 Naujininkai 19 992 Paneriai Source: Lithuanian central 83 heat supply sector review, 2018 Alytus 50% Hot water Heat supply, (GWh) 258 000 meters, units Total number of clients Heat comes VŠT part in total structure Lenth of heat networks, km 54% from RES of all heating companies -

Lithuanians and Poles Against Communism After 1956. Parallel Ways to Freedom?

Lithuanians and Poles against Communism after 1956. Parallel Ways to Freedom? The project has been co-financed by the Department of Public and Cultural Diplomacy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs within the competition ‘Cooperation in the field of public diplomacy 2013.’ The publication expresses only the views of the author and must not be identified with the official stance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The book is available under the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0, Poland. Some rights have been reserved to the authors and the Faculty of International and Po- litical Studies of the Jagiellonian University. This piece has been created as a part of the competition ‘Cooperation in the Field of Public Diplomacy in 2013,’ implemented by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2013. It is permitted to use this work, provided that the above information, including the information on the applicable license, holders of rights and competition ‘Cooperation in the field of public diplomacy 2013’ is included. Translated from Polish by Anna Sekułowicz and Łukasz Moskała Translated from Lithuanian by Aldona Matulytė Copy-edited by Keith Horeschka Cover designe by Bartłomiej Klepiński ISBN 978-609-8086-05-8 © PI Bernardinai.lt, 2015 © Jagiellonian University, 2015 Lithuanians and Poles against Communism after 1956. Parallel Ways to Freedom? Editet by Katarzyna Korzeniewska, Adam Mielczarek, Monika Kareniauskaitė, and Małgorzata Stefanowicz Vilnius 2015 Table of Contents 7 Katarzyna Korzeniewska, Adam Mielczarek, Monika Kareniauskaitė, Małgorzata -

Between National and Academic Agendas Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940

BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Other titles in the same series Södertörn Studies in History Git Claesson Pipping & Tom Olsson, Dyrkan och spektakel: Selma Lagerlöfs framträdanden i offentligheten i Sverige 1909 och Finland 1912, 2010. Heiko Droste (ed.), Connecting the Baltic Area: The Swedish Postal System in the Seventeenth Century, 2011. Susanna Sjödin Lindenskoug, Manlighetens bortre gräns: tidelagsrättegångar i Livland åren 1685–1709, 2011. Anna Rosengren, Åldrandet och språket: En språkhistorisk analys av hög ålder och åldrande i Sverige cirka 1875–1975, 2011. Steffen Werther, SS-Vision und Grenzland-Realität: Vom Umgang dänischer und „volksdeutscher” Nationalsozialisten in Sønderjylland mit der „großgermanischen“ Ideologie der SS, 2012. Södertörn Academic Studies Leif Dahlberg och Hans Ruin (red.), Fenomenologi, teknik och medialitet, 2012. Samuel Edquist, I Ruriks fotspår: Om forntida svenska österledsfärder i modern historieskrivning, 2012. Jonna Bornemark (ed.), Phenomenology of Eros, 2012. Jonna Bornemark och Hans Ruin (eds), Ambiguity of the Sacred, 2012. Håkan Nilsson (ed.), Placing Art in the Public Realm, 2012. Lars Kleberg and Aleksei Semenenko (eds), Aksenov and the Environs/Aksenov i okrestnosti, 2012. BETWEEN NATIONAL AND ACADEMIC AGENDAS Ethnic Policies and ‘National Disciplines’ at the University of Latvia, 1919–1940 PER BOLIN Södertörns högskola Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image, taken from Latvijas Universitāte Illūstrācijās, p. 10. Gulbis, Riga, 1929. Cover: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson and Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Studies in History 13 ISSN 1653-2147 Södertörn Academic Studies 51 ISSN 1650-6162 ISBN 978-91-86069-52-0 Contents Foreword ...................................................................................................................................... -

Memellander/Klaipėdiškiai Identity and German Lithuanian Relations

Identiteto raida. Istorija ir dabartis Vygantas Vareikis Memellander/Klaipėdiškiai Identity and German Lithuanian Relations in Lithuania Minor in the Nine teenth and Twentieth centuries Santrauka XXa. lietuviųistoriografijoje retai svarstytiKl.aipėdos krašto gyventojų(klaipėdiškių/memelende rių), turėjusių dvigubą, panašų į elzasiečių, identitetą klausimai. Paprastai šioji grnpėtapatinama su lietuviais, o klaipėdiškių identiteto reiškinys, jų politinė orientacijaXX a. pirmojepusėje aiškinami kaip aktyvios vokietinimo politikos bei lietuvių tautinės sąmonės silpnumo padariniai. Straipsnyje nagrinėjami klausimai: kaipPrūsijoje (Vokietijoje) gyvenęlietuviai, išlaikydamikalbą ir identiteto savarankiškumą, vykstant akultūracijai, perėmė vokiečių kultūros vertybes ir socialines konvencijas; kokie politiniai veiksniai formavo Prūsijos lietuvių identitetą ir kaip skirtingas Prūsijos (ir Klaipėdos krašto) lietuviškumas veikė Didžiosios Lietuvos lietuvių pažiūras. l. The history of Lithuania and Lithuania Living in a German state the Mažlietuvis was Minor began to follow divergent courses when, naturally prevailed upon to integrate into state during the Middle Ages, the Teutonic Knights political life and naturally became bilingual in conquered the tribes that dwelt on the eastern German and Lithuanian. Especially after the shores of the Baltic Sea. Lithuanians living in industrialisation and modernization of Prussia the lands governed by the Order and then by the Mažlietuvis was bilingual. This bilingualism the dukes of Prussia (after 1525) were -

NONVIOLENT RESISTANCE in LITHUANIA a Story of Peaceful Liberation

NONVIOLENT RESISTANCE IN LITHUANIA A Story of Peaceful Liberation Grazina Miniotaite The Albert Einstein Institution www.aeinstein.org 2 CONTENTS Acknowledgments Introduction Chapter 1: Nonviolent Resistance Against Russification in the Nineteenth Century The Goals of Tsarism in Lithuania The Failure of Colonization The Struggle for the Freedom of Religion The Struggle for Lithuanian Press and Education Chapter 2: Resistance to Soviet Rule, 1940–1987 An Overview Postwar Resistance The Struggle for the Freedom of Faith The Struggle for Human and National Rights The Role of Lithuanian Exiles Chapter 3: The Rebirth From Perestroika to the Independence Movement Test of Fortitude The Triumph of Sajudis Chapter 4: Towards Independence The Struggle for Constitutional Change Civil Disobedience Step by Step The Rise of Reactionary Opposition Chapter 5: The Struggle for International Recognition The Declaration of Independence Independence Buttressed: the Battle of Laws First Signs of International Recognition The Economic Blockade The January Events Nonviolent Action in the January Events International Reaction 3 Chapter 6: Towards Civilian-Based Defense Resistance to the “Creeping Occupation” Elements of Civilian-Based Defense From Nonviolent Resistance to Organized Civilian-Based Defense The Development of Security and Defense Policy in Lithuania since 1992 Concluding Remarks Appendix I Appeal to Lithuanian Youth by the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania Appendix II Republic in Danger! Appendix III Appeal by the Government of the Republic -

Standartizuotų Testų Organizavimas Ir Vykdymas

„Galimybės siekiant ugdymo kokybės“ 2015-11-10, KAUNAS Šiuolaikinis ugdymas ,, ... Svarbiausia dėmesį sutelkti į mokinio 2015.11.10 asmenybės ugdymą, į jo paties aktyvų, sąmoningą mokymąsi, suteikiant mokiniui tinkamą paramą, kad jis išsiugdytų gyvenimui svarbių kompetencijų ...“ Kompetencijų ugdymas. Metodinė knyga mokytojui. 2 Projektas „Pagrindinio ugdymo pirmo koncentro (5 – 8 kl.) mokinių esminių kompetencijų ugdymas“ (Vilnius, 2012, psl. 8) Kompetencija - tam tikros srities ţinių, gebėjimų ir nuostatų visuma, įrodytas gebėjimas atlikti uţduotis, veiksmus pagal sutartus reikalavimus. • Mokyklai keliamas uţdavinys padėti išsiugdyti tiek bendrąsias, tiek dalykines kompetencijas; • Dalykų turinys turi padėti mokiniams ugdytis bendrąsias 2015.11.10 kompetencijas; • Kiekviena šalis sudaro kiek kitokį bendrųjų kompetencijų sąrašą, o mokyklos jį interpretuoja ir pritaiko savo mokiniams. (R. Hipkins, 2006, Europos Parlamento ir Tarybos rekomendacija (2005/0221(COD) • Visos bendrosios kompetencijos nėra izoliuotos, jos susijusios... 3 Kompetencijų ugdymas. Metodinė knyga mokytojui. Projektas „Pagrindinio ugdymo pirmo koncentro (5 – 8 kl.) mokinių esminių kompetencijų ugdymas“ (Vilnius, 2012, psl. 10) Kasdieniai iššūkiai: • ... • Skirtinga motyvacija. 2015.11.10 • Skirtingi mokymosi stiliai. • Skirtingi pasiekimų lygiai. • ... • Kaip sudaryti galimybę kiekvienam siekti paţangos ? 4 Pagrindiniai į kompetencijas orientuoto mokymosi bruoţai • Mokymasis yra aktyvus kuriamasis procesas... • Mokymasis yra sukauptų ţinių ir gebėjimų siejimas... 2015.11.10