International Airline Collaboration in Traffic Pools, Rate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Benjamins V. British European Airways

Finding a Cause of Action for Wrongful Death in the Warsaw Convention: Benjamins v. British European Airways I. INTRODUCTION The United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit decided in Benjamins v. British European Airways' that article 17 of the Warsaw Convention2 is self-executing. That is, the treaty alone, without additional legislative action, now creates a cause of action for wrongful death. The facts of the case are simple; on June 18, 1972, an airplane designed and manufactured by Hawker-Siddely Aviation, Ltd. and owned and operated by British European Airways departed for Brussels from London's Heathrow Airport. Soon thereafter, the plane crashed into a field, killing all 112 passengers. Abraham Benjamins, the spouse of one of the passengers, brought suit for wrongful death and baggage loss in the Eastern District of New York as representative of his wife's estate. Plaintiff was a Dutch citizen permanently residing in California. Defendants were British corporations with their principal places of business in the United Kingdom. The ticket on which the decedent was traveling had been purchased in Los Angeles. The original complaint alleged only diversity of citizenship as grounds for federal jurisdiction;3 because Benjamins, a resident alien, could not be diverse from an alien corporation,4 the complaint was dismissed. Benjamins' suit reached the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit after the district court, in an unreported decision, dismissed an amended complaint asserting federal question jurisdiction.5 The Second Circuit 1. 572 F.2d 913 (2d Cir. 1978). 2. Convention for the Unification of Certain Rules Relating to InternationalTransportation by Air, 49 Stat. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

No. 16673 SWEDEN and IRAN Air Transport Agreement

No. 16673 SWEDEN and IRAN Air Transport Agreement (with annex and related note). Signed at Tehran on 10 June 1975 Authentic texts of the Agreement and annex: Swedish, Persian and English. Authentic text of the related note: English. Registered by the International Civil Aviation Organization on 5 May 1978. SUÈDE et IRAN Accord relatif aux transports aériens (avec annexe et note connexe). Signé à Téhéran le 10 juin 1975 Textes authentiques de l©Accord et de l©annexe : su dois, persan et anglais. Texte authentique de la note connexe : anglais. Enregistr par l©Organisation de l©aviation civile internationale le 5 mai 1978. Vol. 1088,1-16673 1978_____United Nations — Treaty Series • Nations Unies — Recueil des Traités_____283 AIR TRANSPORT AGREEMENT1 BETWEEN THE GOVERNMENT OF THE KINGDOM OF SWEDEN AND THE IMPERIAL GOVERN MENT OF IRAN The Government of the Kingdom of Sweden and the Imperial Government of Iran, Being equally desirous to conclude an Agreement for the purpose of establishing and operating commercial air services between and beyond their respective terri tories, have agreed as follows: Article 1. DEFINITIONS For the purpose of the present Agreement, unless the context otherwise requires: à) The term "aeronautical authorities" means, in the case of Iran, the Depart ment General of Civil Aviation, and any person or body authorized to perform any functions at present exercised by the said Department General or similar functions, and, in the case of Sweden, the Board of Civil Aviation, and any person or body authorized to perform any functions at present exercised by the said Board or similar functions. -

Air Transport

The History of Air Transport KOSTAS IATROU Dedicated to my wife Evgenia and my sons George and Yianni Copyright © 2020: Kostas Iatrou First Edition: July 2020 Published by: Hermes – Air Transport Organisation Graphic Design – Layout: Sophia Darviris Material (either in whole or in part) from this publication may not be published, photocopied, rewritten, transferred through any electronical or other means, without prior permission by the publisher. Preface ommercial aviation recently celebrated its first centennial. Over the more than 100 years since the first Ctake off, aviation has witnessed challenges and changes that have made it a critical component of mod- ern societies. Most importantly, air transport brings humans closer together, promoting peace and harmo- ny through connectivity and social exchange. A key role for Hermes Air Transport Organisation is to contribute to the development, progress and promo- tion of air transport at the global level. This would not be possible without knowing the history and evolu- tion of the industry. Once a luxury service, affordable to only a few, aviation has evolved to become accessible to billions of peo- ple. But how did this evolution occur? This book provides an updated timeline of the key moments of air transport. It is based on the first aviation history book Hermes published in 2014 in partnership with ICAO, ACI, CANSO & IATA. I would like to express my appreciation to Professor Martin Dresner, Chair of the Hermes Report Committee, for his important role in editing the contents of the book. I would also like to thank Hermes members and partners who have helped to make Hermes a key organisa- tion in the air transport field. -

Innehåll R E

S A S k o n c e r n e n s Å r s Innehåll r e d Affärsområde o 2 SAS koncernen v i 57 Hotels s Årets resultat 2 n Översikt, resultat och sammandrag 57 i SAS koncernen - styrmodell, styrfilosofi och nyckeltal 3 n g Översikt affärsområden 4 Varumärken, partners och hotellutveckling 59 & VD har ordet 6 Marknadsutsikter 60 H å Viktiga händelser 8 l l b a Kommersiell offensiv 9 r h Affärsidé, vision, mål & värderingar 10 e t s SAS koncernens strategier 11 61 Ekonomisk redovisning r e Turnaround 2005 13 d Förvaltningsberättelse 61 o Marknader & konkurrentanalys 15 v SAS koncernen i s Värde & tillväxt 16 n - Resultaträkning, inkl. kommentarer 66 i n På kundens villkor 18 - Resultat i sammandrag 67 g 2 Allianssamarbete 20 - Balansräkning, inkl. kommentarer 68 0 Kvalitet & säkerhet 22 0 - Förändring i eget kapital 69 4 - Kassaflödesanalys, inkl. kommentarer 70 23 Kapitalmarknaden - Redovisnings- och värderingsprinciper 71 Aktien 24 - Noter/tilläggsupplysningar 74 Ekonomisk tioårsöversikt inkl. kommentarer 26 SAS AB, moderbolaget, resultat- och balansräkning, Avkastningskrav & resultatkrav 28 kassaflödesanalys, förändring i eget kapital samt noter 88 Risker & känslighet 29 Förslag till vinstdisposition och Revisionsberättelse 90 Investeringar & kapitalbindning 31 Affärsområde 33 Scandinavian Airlines Businesses Scandinavian Airlines Danmark 36 91 Corporate Governance SAS Braathens 37 Ordföranden har ordet 94 Scandinavian Airlines Sverige 38 Styrelse & revisorer 95 Scandinavian Airlines International 39 SAS koncernens organisationsstruktur & legal struktur 96 Operationella nyckeltal - tioårsöversikt 40 Koncernledning 97 Historisk återblick 98 Affärsområde 41 Subsidiary & Affiliated Airlines På kundens Spanair 43 Widerøe 45 99 Hållbarhetsredovisning Blue1 46 SAS koncernens Hållbarhetsredovisning 2004 har villkor Business Economy Flex Economy airBaltic 47 granskats av koncernens externa revisorer. -

Milan Linate (LIN) J Ownership and Organisational Structure the Airport

Competition between Airports and the Application of Sfare Aid Rules Volume H ~ Country Reports Italy Milan Linate (LIN) J Ownership and organisational structure The airport is part of Gruppo SEA (Milan Airports). Ownership is 14.6% local government and 84.6% City of Milan. Other shareholders hold the remaining 0.8%. Privatisation (partial) was scheduled for the end of 2001 but was stopped after the events of 11th September. Now the proposed date is October 2002 but this has still to be finalised. Only 30% of the shareholding will be moved into the private sector with no shareholder having more than 5%. There are no legislative changes required. The provision of airport services is shared between ENAV (ATC), Italian police (police), SEA (security), ATA and SEA Handling (passenger and ramp handling), Dufntal (duty-free) and SEA Parking (car parking). There are no current environmental issues but, in the future, there is a possible night ban and charges imposed according to aircraft noise. 2 Type ofairpo Milan Linate is a city-centre (almost) airport that serves mainly the scheduled domestic and international market with a growing low-cost airline presence (Buzz, Go). There is very little charter and cargo traffic but some General Aviation. The airport is subject to traffic distribution rules imposed by the Italian government with the aim of 'encouraging' airlines to move to Malpensa. Traffic Data (2000) Domestic fíghts Scheduled Charter Total Terminal Passengers (arrivals) 2 103 341 _ 2 103 341 Terminal Passengers (departures) 2 084 008 -

The UK Domestic Air Transport System: How and Why Is It Changing?

The UK domestic air transport system: how and why is it changing? Future of Mobility: Evidence Review Foresight, Government Office for Science The UK domestic air transport system: how and why is it changing? The UK domestic air transport system: how and why is it changing? Dr Lucy Budd Reader in Air Transport, Loughborough University Professor Stephen Ison Professor of Transport Policy, Loughborough University February 2019 This review has been commissioned as part of the UK government’s Foresight Future of Mobility project. The views expressed are those of the author and do not represent those of any government or organisation. This document is not a statement of government policy. This report has an information cut-off date of September 2018. The UK domestic air transport system: how and why is it changing? Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Scope of the review ............................................................................................................................. 4 Scale and operational characteristics of UK domestic air transport ...................................................... 4 Development and regulation of UK domestic air transport .................................................................... 5 Trends in UK domestic -

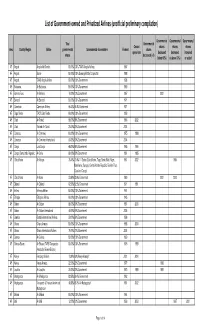

List of Government-Owned and Privatized Airlines (Unofficial Preliminary Compilation)

List of Government-owned and Privatized Airlines (unofficial preliminary compilation) Governmental Governmental Governmental Total Governmental Ceased shares shares shares Area Country/Region Airline governmental Governmental shareholders Formed shares operations decreased decreased increased shares decreased (=0) (below 50%) (=/above 50%) or added AF Angola Angola Air Charter 100.00% 100% TAAG Angola Airlines 1987 AF Angola Sonair 100.00% 100% Sonangol State Corporation 1998 AF Angola TAAG Angola Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1938 AF Botswana Air Botswana 100.00% 100% Government 1969 AF Burkina Faso Air Burkina 10.00% 10% Government 1967 2001 AF Burundi Air Burundi 100.00% 100% Government 1971 AF Cameroon Cameroon Airlines 96.43% 96.4% Government 1971 AF Cape Verde TACV Cabo Verde 100.00% 100% Government 1958 AF Chad Air Tchad 98.00% 98% Government 1966 2002 AF Chad Toumai Air Tchad 25.00% 25% Government 2004 AF Comoros Air Comores 100.00% 100% Government 1975 1998 AF Comoros Air Comores International 60.00% 60% Government 2004 AF Congo Lina Congo 66.00% 66% Government 1965 1999 AF Congo, Democratic Republic Air Zaire 80.00% 80% Government 1961 1995 AF Cofôte d'Ivoire Air Afrique 70.40% 70.4% 11 States (Cote d'Ivoire, Togo, Benin, Mali, Niger, 1961 2002 1994 Mauritania, Senegal, Central African Republic, Burkino Faso, Chad and Congo) AF Côte d'Ivoire Air Ivoire 23.60% 23.6% Government 1960 2001 2000 AF Djibouti Air Djibouti 62.50% 62.5% Government 1971 1991 AF Eritrea Eritrean Airlines 100.00% 100% Government 1991 AF Ethiopia Ethiopian -

British Airways Profile

SECTION 2 - BRITISH AIRWAYS PROFILE OVERVIEW British Airways is the world's second biggest international airline, carrying more than 28 million passengers from one country to another. Also, one of the world’s longest established airlines, it has always been regarded as an industry-leader. The airline’s two main operating bases are London’s two main airports, Heathrow (the world’s biggest international airport) and Gatwick. Last year, more than 34 million people chose to fly on flights operated by British Airways. While British Airways is the world’s second largest international airline, because its US competitors carry so many passengers on domestic flights, it is the fifth biggest in overall passenger carryings (in terms of revenue passenger kilometres). During 2001/02 revenue passenger kilometres for the Group fell by 13.7 per cent, against a capacity decrease of 9.3 per cent (measured in available tonne kilometres). This resulted in Group passenger load factor of 70.4 per cent, down from 71.4 per cent the previous year. The airline also carried more than 750 tonnes of cargo last year (down 17.4 per cent on the previous year). The significant drop in both passengers and cargo carried was a reflection of the difficult trading conditions resulting from the weakening of the global economy, the impact of the foot and mouth epidemic in the UK and effects of the September 11th US terrorist attacks. An average of 61,460 staff were employed by the Group world-wide in 2001-2002, 81.0 per cent of them based in the UK. -

PROTOCOL at the Moment of Signing the Agreement Between the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Government Of

PROTOCOL At the moment of signing the Agreement between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Kingdom of Sweden for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with respect to Taxes on Income, the undersigned have agreed that the following provisions shall form an intergral part of the Agreement. To Articles 8 and 13 1. The provisions of Article 9 of the Agreement on Maritime Transport between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of Sweden signed at Beijing on the 18th of January 1975 shall not be affected by the Agreement. 2. When applying the Agreement the air transport consortium Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) shall be regarded as having its head office in Sweden but the provisions of paragraph 1 of Article 8 and paragraph 3 of Article 13 shall apply only to that part of its profits as corresponds to the participation held in that consortium by AB Aerotransport (ABA), the Swedish partner of Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) . To Article 12 For purposes of paragraph 3 of Article 12 it is understood that, in the case of payments received as a consideration for the use of or the right to use industrial, commercial or scientific equipment, the tax shall be imposed on 70 per cent of the gross amount of such payments. To Article 15 It is understood that where a resident of Sweden derives remuneration in respect of an employment exercised aboard an aircraft operated in international traffic by the air transport consortium Scandinavian Airlines System (SAS) such remuneration shall be taxable only in Sweden. -

Focus 40.Pdf

16894/Flight Safety cover 29/8/08 10:38 Page 1 ON COMMERCIAL AVIATION SAFETY AUTUMN 2000 This issue of focus sponsored by: THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE ISSUE 40 UNITED KNIGDOM FLIGHT SAFETY COMMITTEE ISSN 1335-1523 16894/Flight Safety 24pgr 29/8/08 10:40 Page 1 The Official Publication of THE UNITED KINGDOM FLIGHT SAFETY COMMITTEE ISSN: 1335-1523 AUTUMN 2000 ON COMMERCIAL AVIATION SAFETY FOCUS on Commercial Aviation Safety contents is published quarterly by The UK Flight Safety Committee. Editorial 2 Editorial Office: Ed Paintin Chairman’s Column 3 The Graham Suite Fairoaks Airport, Chobham, Woking, Surrey. GU24 8HX Is My Top Management 4 Tel: 01276-855193 Fax: 855195 “Safety Management Orientated”? e-mail: [email protected] Mike Overall Web Site: www.ukfsc.co.uk Office Hours: 0900-1630 Monday-Friday Crew Resource Management 7 Advertisement Sales Office: Stalled at a Crossroads and Seeking to Interpret the Markers Andrew Phillips Pieter Hemsley Andrew Phillips Partnership 39 Hale Reeds CRM? .....It’s For The Birds! 1 0 Farnham, Surrey. GU9 9BN Tel: 01252-712434 Mobile: 0836-677377 Corporate Killing - Directors Liabilities 1 1 FOCUS on Commercial Aviation Safety is Steven Kay QC circulated to commercial pilots, flight engineers and air traffic control officers holding current licences. It is also Book Review 1 3 available on subscription to organisations Human Factors in Multi-Crew Flight Operations or individuals at a cost of £12 (+p&p) per annum. The Quality Choice 1 5 Alan Munro FOCUS is produced solely for the purpose of improving flight safety and, unless copyright is indicated, articles may Leading the Way Towards Safer Flying 1 8 be reproduced providing that the source Dave Wright of material is acknowledged. -

A Critique of the C.A.A. Studies on Air Traffic Generation in the United States G

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 20 | Issue 2 Article 3 1953 A Critique of the C.A.A. Studies on Air Traffic Generation in the United States G. Roger Mayhill Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation G. Roger Mayhill, A Critique of the C.A.A. Studies on Air Traffic Generation in the United States, 20 J. Air L. & Com. 158 (1953) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol20/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. A CRITIQUE OF THE C.A.A. STUDIES ON AIR TRAFFIC GENERATION IN THE UNITED STATES By G. ROGER MAYHILL Assistant Professor of Economics and Air Transportation, Pur- due University; B.S., Purdue, 1932; M.A., University of Illinois, 1935; Ph.D., University of Illinois, 1942; M.B.A., New York Univer- sity, 1952 - Lieut. U.S.N.R. - Joint author, Air Traffic Potentials in the New York Garment Industry, 1946. T HE basic work of D'Arcy Harvey and other C.A.A. pioneers in air traffic generation has more important and farreaching significance than often is realized. This observation is true because these studies are being used: (1) As the economic basis for the Natonal Airport Plan; (2) As a decisive element in the installation of landing aids, towers and radar instruments at airports; (3) As a definite factor in establshing new airways; (4) As a guide for deciding the need for new airline routes; and (5) As an important consideration in the present proposed air- line consolidation cases.