Bernice Garcia Gutierrez: My Name Is Bernice Garcia Gutierrez and Today Is May 13, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master's

Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of Global Studies Jerónimo Arellano, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Global Studies by Sarah Mabry August 2018 Transculturalism in Chicano Literature, Visual Art, and Film Copyright by Sarah Mabry © 2018 Dedication Here I acknowledge those individuals by name and those remaining anonymous that have encouraged and inspired me on this journey. First, I would like to dedicate this to my great grandfather, Jerome Head, a surgeon, published author, and painter. Although we never had the opportunity to meet on this earth, you passed along your works of literature and art. Gleaned from your manuscript entitled A Search for Solomon, ¨As is so often the way with quests, whether they be for fish or buried cities or mountain peaks or even for money or any other goal that one sets himself in life, the rewards are usually incidental to the journeying rather than in the end itself…I have come to enjoy the journeying.” I consider this project as a quest of discovery, rediscovery, and delightful unexpected turns. I would like mention one of Jerome’s six sons, my grandfather, Charles Rollin Head, a farmer by trade and an intellectual at heart. I remember your Chevy pickup truck filled with farm supplies rattling under the backseat and a tape cassette playing Mozart’s piano sonata No. 16. This old vehicle metaphorically carried a hard work ethic together with an artistic sensibility. -

Labor Rights Community Mobilization

Labor Rights Community Mobilization Working Conditions Immigration Health Education Occupational Safety Empowerment Living Conditions Environmental Justice 2 017 ANNUAL REPORT Empowering Farmworkers to Transform Our Food System ROM the desk of the President Dear friends, President Trump and his Cabinet began to act on their promised radical de-regulation to benefit Farmworker Justice is pleased to review the impact of businesses at the expense of workers, consumers and this vital organization during 2017. the environment. He supported large tax cuts for rich The Board of Directors and staff are driven by a vision people and huge reductions in government programs, of a future in which all farmworkers, their families including cutting off access to health care for millions and their communities thrive. of people. We help farmworkers in their struggles for better Harsh immigration enforcement separated farmworker workplace practices, fair government policies and families and instilled fear in farmworker communities, programs, improved health and access to health care, exacerbating the problems caused by our broken and a responsible food system. immigration system. Immigration policy and guestworker programs Farmworker Justice vowed to fight back against remain a high priority because the large majority proposals by Trump and an unfriendly Congress and, of the nation’s 2.4 million farmworkers are while the battles are not over, we helped stop some of immigrants. Harsh immigration enforcement is the serious harm they sought to inflict. hurting farmworkers, more than one-half of whom are In addition, we have assisted many affirmative undocumented. Employers increasingly are using the efforts, including farmworker organizing, state- abusive agricultural guestworker program. -

Centro Cultural De La Raza Archives CEMA 12

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Online items available Guide to the Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives CEMA 12 Finding aid prepared by Project director Sal Güereña, principle processor Michelle Wilder, assistant processors Susana Castillo and Alexander Hauschild June, 2006. Collection was processed with support from the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS). Updated 2011 by Callie Bowdish and Clarence M. Chan University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 (805) 893-8563 [email protected] © 2006 Guide to the Centro Cultural de la CEMA 12 1 Raza Archives CEMA 12 Title: Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 12 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 83.0 linear feet(153 document boxes, 5 oversize boxes, 13 slide albums, 229 posters, and 975 online items)Online items available Date (inclusive): 1970-1999 Abstract: Slides and other materials relating to the San Diego artists' collective, co-founded in 1970 by Chicano poet Alurista and artist Victor Ochoa. Known as a center of indigenismo (indigenism) during the Aztlán phase of Chicano art in the early 1970s. (CEMA 12). Physical location: All processed material is located in Del Norte and any uncataloged material (silk screens) is stored in map drawers in CEMA. General Physical Description note: (153 document boxes and 5 oversize boxes).Online items available creator: Centro Cultural de la Raza http://content.cdlib.org/search?style=oac-img&sort=title&relation=ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Access Restrictions None. -

University of California, Santa Barbara Davidson Library Department of Special Collections California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives

University of California, Santa Barbara Davidson Library Department of Special Collections California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives GUIDE TO THE SALVADOR ROBERTO TORRES PAPERS 1934-2009 (bulk 1962-2002) Collection Number: CEMA 38. Size Collection: 10.5 linear feet (21 boxes), ten albums of 2,590 slides, and audiovisual materials. Acquisition Information: Donated by Salvador Roberto Torres, Dec. 12, 1998. Access restrictions: None. Use Restriction: Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained. Processing Information: Principal processor Susana Castillo, 2002-2003 (papers) and Benjamin Wood, 2004- 2006 (slides). Supported by the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS). Location: Del Norte. BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Salvador Roberto Torres is a Chicano (Mexican American) artist, born in El Paso Texas, on July 3, 1936. He is considered to be an important and influential figure in the Chicano art movement, owing as much to his art as to his civic work as a cultural activist. Torres’ primary media are painting and mural painting. Selected exhibitions that have included his work are “Califas: Chicano Art and Culture in California” (University of California, Santa Cruz, 1981), “Salvador Roberto Torres” (Hyde Gallery, Grossmont College, San Diego, 1988), the nationally touring “Chicano Art: Resistance and Affirmation: 1965-1985”, (Wight Art Gallery, UCLA, 1990-1993), “International Chicano Art Exhibition” (San Diego, 1999), “Viva la Raza Art Exhibition” (San Diego Repertory Theater Gallery, 2000), and “Made in California: 1900-2000” (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2000). -

Chicano Park and the Chicano Park Murals a National Register Nomination

CHICANO PARK AND THE CHICANO PARK MURALS A NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION Josie S. Talamantez B.A., University of California, Berkeley, 1975 PROJECT Submitted in partial satisfaction of The requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HISTORY (Public History) at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2011 CHICANO PARK AND THE CHICANO PARK MURALS A NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION A Project by Josie S. Talamantez Approved by: _______________________________, Committee Chair Dr. Lee Simpson _______________________________, Second Reader Dr. Patrick Ettinger _______________________________ Date ii Student:____Josie S. Talamantez I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and this Project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the Project. ______________________, Department Chair ____________________ Aaron Cohen, Ph.D. Date Department of History iii Abstract of CHICANO PARK AND THE CHICANO PARK MURALS A NATIONAL REGISTER NOMINATION by Josie S. Talamantez Chicano Park and the Chicano Park Murals Chicano Park is a 7.4-acre park located in San Diego City’s Barrio Logan beneath the east-west approach ramps of the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge where the bridge bisects Interstate 5. The park was created in 1970 after residents in Barrio Logan participated in a “takeover” of land that was being prepared for a substation of the California Highway Patrol. Barrio Logan the second largest barrio on the West Coast until national and state transportation and urban renewal public policies, of the 1950’s and 1960’s, relocated thousands of residents from their self-contained neighborhood to create Interstate 5, to rezone the area from residential to light industrial, and to build the San Diego-Coronado Bay Bridge. -

The Relation of Gloria Anzaldúa's Mestiza Consciousness to Mexican American Performance A

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 10-26-2010 Visualizando la Conciencia Mestiza: The Relation of Gloria Anzaldúa’s Mestiza Consciousness to Mexican American Performance and Poster Art Maria Cristina Serrano University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Serrano, Maria Cristina, "Visualizando la Conciencia Mestiza: The Relation of Gloria Anzaldúa’s Mestiza Consciousness to Mexican American Performance and Poster Art" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/3591 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Visualizando la Conciencia Mestiza: The Relation of Gloria Anzaldúa’s Mestiza Consciousness to Mexican American Performance and Poster Art by Maria Cristina Serrano A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Adriana Novoa, Ph.D. Ylce Irizarry, Ph.D. Date of Approval: October 26, 2010 Chicano/a, border art, immigration, hybridity, borderlands Copyright © 2010, Maria Cristina Serrano Table of Contents -

Chicano Studies Research Center Annual Report 2018-2019 Submitted by Director Chon A. Noriega in Memory of Leobardo F. Estrada

Chicano Studies Research Center Annual Report 2018-2019 Submitted by Director Chon A. Noriega In memory of Leobardo F. Estrada (1945-2018) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE 3 HIGHLIGHTS 5 II. DEVELOPMENT REPORT 8 III. ADMINISTRATION, STAFF, FACULTY, AND ASSOCIATES 11 IV. ACADEMIC AND COMMUNITY RELATIONS 14 V. LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE 26 VI. PRESS 43 VII. RESEARCH 58 VIII. FACILITIES 75 APPENDICES 77 2 I. DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE The UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center (CSRC) was founded in 1969 with a commitment to foster multi-disciplinary research as part of the overall mission of the university. It is one of four ethnic studies centers within the Institute of American Cultures (IAC), which reports to the UCLA Office of the Chancellor. The CSRC is also a co-founder and serves as the official archive of the Inter-University Program for Latino Research (IUPLR, est. 1983), a consortium of Latino research centers that now includes twenty-five institutions dedicated to increasing the number of scholars and intellectual leaders conducting Latino-focused research. The CSRC houses a library and special collections archive, an academic press, externally-funded research projects, community-based partnerships, competitive grant and fellowship programs, and several gift funds. It maintains a public programs calendar on campus and at local, national, and international venues. The CSRC also maintains strategic research partnerships with UCLA schools, departments, and research centers, as well as with major museums across the U.S. The CSRC holds six (6) positions for faculty that are appointed in academic departments. These appointments expand the CSRC’s research capacity as well as the curriculum in Chicana/o and Latina/o studies across UCLA. -

Journal of San Diego History V 50, No 1&2

T HE J OURNAL OF SANDIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/ SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 IRIS H. W. ENGSTRAND MOLLY MCCLAIN Editors COLIN FISHER DAWN M. RIGGS Review Editors MATTHEW BOKOVOY Contributing Editor Published since 1955 by the SAN DIEGO HISTORICAL SOCIETY Post Office Box 81825, San Diego, California 92138 ISSN 0022-4383 T HE J OURNAL OF SAN DIEGO HISTORy VOLUME 50 ■ WINTER/SPRING 2004 ■ NUMBERS 1 & 2 Editorial Consultants Published quarterly by the MATTHEW BOKOVOY San Diego Historical Society at University of Oklahoma 1649 El Prado, Balboa Park, San Diego, California 92101 DONALD C. CUTTER Albuquerque, New Mexico A $50.00 annual membership in the San WILLIAM DEVERELL Diego Historical Society includes subscrip- University of Southern California; Director, Huntington-USC Institute on California tion to The Journal of San Diego History and and the West the SDHS Times. Back issues and microfilm copies are available. VICTOR GERACI University of California, Berkeley Articles and book reviews for publication PHOEBE KROPP consideration, as well as editorial correspon- University of Pennsylvania dence should be addressed to the ROGER W. LOTCHIN Editors, The Journal of San Diego History University of North Carolina Department of History, University of San at Chapel Hill Diego, 5998 Alcala Park, San Diego, CA NEIL MORGAN 92110 Journalist DOYCE B. NUNIS, JR. All article submittals should be typed and University of Southern California double spaced, and follow the Chicago Manual of Style. Authors should submit four JOHN PUTMAN San Diego State University copies of their manuscript, plus an electronic copy, in MS Word or in rich text format ANDREW ROLLE (RTF). -

Copyright by Ann Marie Leimer 2005

Copyright by Ann Marie Leimer 2005 The Dissertation Committee for Ann Marie Leimer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Performing the Sacred: The Concept of Journey in Codex Delilah Committee: _________________________________ Amelia Malagamba, Supervisor _________________________________ Jacqueline Barnitz _________________________________ Richard R. Flores _________________________________ Julia E. Guernsey _________________________________ Ann Reynolds Performing the Sacred: The Concept of Journey in Codex Delilah by Ann Marie Leimer, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2005 This dissertation is lovingly dedicated to the memory of Cleofas Mena, Partera y Curandera of Crystal City, Texas 1886 – 1970 and to her grandson Jesús Manuel Mena Garza Acknowledgements Many people have helped me bring the dissertation to fruition. There are no words to adequately recognize the patience and support provided by my husband Jesús during the years I worked on this project. His unending thoughtfulness and ready wit enlivened the process. I drew inspiration from my step-daughters Estrella and Esperanza and my granddaughters Marissa and the newly emerged Ava. I would like to thank my parents, Tom and Rachel, and my brothers and sisters and their families for their love and kind words of encouragement. I would also like to thank the extended Garza family for their many kindnesses and welcome embrace. I want to recognize the late Miriam Castellan del Solar, Daniel del Solar, Karen Hirst, Elizabeth Rigalli, Dr. -

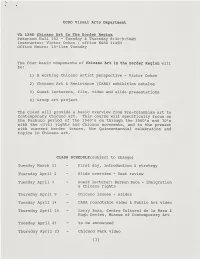

UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art

- UCSD Visual Arts Department VA 128D Chicano Art In The Border Region Peterson Hall 102 - Tuesday & Thursday 8:30-9:50AM Instructor: Victor Ochoa / office H&SS 1145D Office Hours: 10-11am Tuesday The four basic components of Chicano Art in the Border Region will be: 1) A working Chicano artist perspective - Victor Ochoa 2) Chicano Art & Resistance (CARA) exhibition catalog 3) Guest lecturers, film, video and slide presentations 4) Group art project The class will provide a basic overview from Pre-Colombian art to Contemporary Chicano art. This course will specifically focus on the Pachuco period of the 1940's on through the 1960's and 70's with the civil rights and Chicano movements, and to the present with current border issues, the Quincentennial celebration and topics in Chicana art. CLASS SCHEDULE(subject to change) Tuesday March 31 First day, introduction & strategy Thursday April 2 Slide overview - Text review Tuesday April 7 Guest lecturer: Herman Baca - immigration & Chicano rights Thursday April 9 - Chicano issues - slides Tuesday April 14 - CARA roundtable video & Public Art video Thursday April 16 - Larry Baza, Centro Cultural de la Raza & Hugh Davies, Museum of Contemporary Art Tuesday April 21 - to be announced Thursday April 23 - Chicano Park video [1] VA 128D(cont.) Saturday April 25 - Chicano Park Day - required field trip Tuesday April 28 - Issac Artenstein - "Mi Otro Yo" & video potpourri Thursday April 30 - Ireina Cervantes: personal work, Chicanas & Frida (Midterm due) Tuesday May 5 - David Avalos & BAW/TAF the -

Americans in the 1990S: Politics, Policies, and Perceptions

Mexican Americans in the 1990s: Politics, Policies, and Perceptions Item Type Book Authors Garcia, Juan R.; Gelsinon, Thomas Publisher Mexican American Studies & Research Center, The University of Arizona (Tucson, AZ) Journal Perspectives in Mexican American Studies Rights Copyright © Arizona Board of Regents Download date 28/09/2021 13:47:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/624835 Mexican American Studies ; MEXICAN AMERICANS IN THE 1990s: POLITICS, POLICIES, AND PERCEPTIONS Perspectives in Mexican American Studies is an ongoing series devoted to Chicano /a research. Focusing on Mexican Americans as a national group, Perspectives features articles and essays that cover research from the pre - Colombian era to the present. All selections published in Perspectives are refereed. Perspectives is published by the Mexican American Studies & Research Center at the University of Arizona and is distributed by the University of Arizona Press, 1230 N. Park Avenue, Tucson, Arizona 85719. Individual copies are $15. Subscriptions to Perspectives (2 issues) are $25 for individuals and $35 for institutions. Foreign individual subscriptions are $28 and foreign institu- tional subscriptions are $44. For subscription orders, contact the Mexican American Studies & Research Center, Economics Building, Room 208, the University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721 -0023. Manuscripts and inquiries should be sent to Professor Juan R. García, De- partment of History, the University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721. For additional information, call MASRC Publications (520) 621 -7551. Perspectives is abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. Copyright@ 1997 by The Arizona Board of Regents. All rights reserved. ISSN 0889 -8448 ISBN 0- 939363 -06 -2 PERSPECTIVES IN MEXICAN AMERICAN STUDIES Volume 6 1997 Mexican American Studies & Research Center The University of Arizona Tucson MEXICAN AMERICANS IN THE 1990s: POLITICS, POLICIES, AND PERCEPTIONS Editor Juan R. -

Global Migration and Economic Change in Woodburn, Oregon

21 st Century Rural Life at the End of the Oregon Trail: Global Migration and Economic Change In Woodburn, Oregon by Edward Kissam [email protected] with Lynn Stephen Anna Garcia October 8, 2006 Aguirre Division, JBS International 555 Airport Blvd. – Suite 400, Burlingame, California 94010 This material is based upon work supported by the Cooperative State Research, Education, and Extension Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture under Agreement No. 2001-36201-11286. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Acknowledgments Over the 5 years we conducted the New Pluralism study in Woodburn, Oregon, a wide range of people supported the project in diverse ways—in planning this study, conducting research, and in commenting on interim reports. I would like first of all to thank the project research team for their tireless and dedicated work on the Woodburn Community Case Study. Anna Garcia joined me in conducting the initial field research in Woodburn during the summer of 2002 and subsequently provided field research supervision survey activities throughout 2003, as well as ongoing field in-depth field research of her own. Lynn Stephen of the University of Oregon was a marvelous collaborator and skilled field researcher. In addition to conducting a number of key interviews herself, she recruited and worked closely with us in supervising a skilled team of researchers drawn from her students at the University of Oregon. Rachel Hansen, from the graduate program in Anthropology at the University of Oregon was a real pioneer in the study, conducting our first interviews in Woodburn during the spring of 2003 under very challenging circumstances.