Journal of San Diego History V 50, No 1&2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

Dissertation-Master Copy

Coloniality and Border(ed) Violence: San Diego, San Ysidro and the U-S///Mexico Border By Roberto Delgadillo Hernández A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Ramón Grosfoguel, Chair Professor José David Saldívar Professor Ignacio Chapela Professor Joseph Nevins Fall 2010 Coloniality and Border(ed) Violence: San Diego, San Ysidro and the U-S///Mexico Border © Copyright, 2010 By Roberto Delgadillo Hernández Abstract Coloniality and Border(ed) Violence: San Diego, San Ysidro and the U-S///Mexico Border By Roberto Delgadillo Hernández Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies University of California, Berkeley Professor Ramón Grosfoguel, Chair Considered the “World's Busiest Border Crossing,” the San Ysidro port of entry is located in a small, predominantly Mexican and Spanish-speaking community between San Diego and Tijuana. The community of San Ysidro was itself annexed by the City of San Diego in the mid-1950s, in what was publicly articulated as a dispute over water rights. This dissertation argues that the annexation was over who was to have control of the port of entry, and would in turn, set the stage for a gendered/racialized power struggle that has contributed to both real and symbolic violence on the border. This dissertation is situated at the crossroads of urban studies, border studies and ethnic studies and places violence as a central analytical category. As such, this interdisciplinary work is manifold. It is a community history of San Ysidro in its simultaneous relationship to the U-S///Mexico border and to the City of San Diego. -

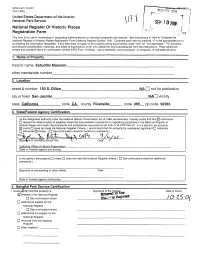

Ctffta Ignaljjre of Certifying Official/Title ' Daw (

NFS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register Of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the" National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Estudillo Mansion_____________________________________ other names/site number__________________________________________ 2. Location street & number 150 S. Dillon________________ NA CH not for publication city or town San Jacinto____________________ ___NAD vicinity state California_______ code CA county Riverside. code 065_ zip code 92583 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this 12 nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for -

Summer 2019, Volume 65, Number 2

The Journal of The Journal of SanSan DiegoDiego HistoryHistory The Journal of San Diego History The San Diego History Center, founded as the San Diego Historical Society in 1928, has always been the catalyst for the preservation and promotion of the history of the San Diego region. The San Diego History Center makes history interesting and fun and seeks to engage audiences of all ages in connecting the past to the present and to set the stage for where our community is headed in the future. The organization operates museums in two National Historic Districts, the San Diego History Center and Research Archives in Balboa Park, and the Junípero Serra Museum in Presidio Park. The History Center is a lifelong learning center for all members of the community, providing outstanding educational programs for schoolchildren and popular programs for families and adults. The Research Archives serves residents, scholars, students, and researchers onsite and online. With its rich historical content, archived material, and online photo gallery, the San Diego History Center’s website is used by more than 1 million visitors annually. The San Diego History Center is a Smithsonian Affiliate and one of the oldest and largest historical organizations on the West Coast. Front Cover: Illustration by contemporary artist Gene Locklear of Kumeyaay observing the settlement on Presidio Hill, c. 1770. Back Cover: View of Presidio Hill looking southwest, c. 1874 (SDHC #11675-2). Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Copy Edits: Samantha Alberts Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. -

1916 - the Missions and Missionaries of California, Index to Volumes II-IV, Zephyrin Engelhardt

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Franciscan Publications Spanish Viceroyalty [AD 1542/1769-1821] 2-14-2019 1916 - The Missions and Missionaries of California, Index to Volumes II-IV, Zephyrin Engelhardt Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_spa_2 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, Law Commons, Life Sciences Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation "1916 - The Missions and Missionaries of California, Index to Volumes II-IV, Zephyrin Engelhardt" (2019). Franciscan Publications. 12. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/hornbeck_spa_2/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Spanish Viceroyalty [AD 1542/1769-1821] at Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Franciscan Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T C 1/ v-snmne v *<t) \^H A Slsd. -^V^^^NV^ SraS^^iL' \\yfr THE, FBANOISOAN MISSIONS E THE MISSIONS AND MISSIONARIES OF CALIFORNIA BY FR. ZEPHYRIN ENGELHARDT, O. F. M. AUTHOR OF <p I "The Franciscans in California" "The Franciscans in Arizona" ' ' ' ' The Holy JXCan of Santa Clara INDEX TO VOLS. II -IV ' El alma de la hUtoria es la verdad sencilla. Pal6u, Prol. de la Vida SUPERIORUM PERMISSU ST. PETER'S GmTO 816 SOUTH C CHICAGO, SAN FRANCISCO, CAL. THE JAMES H. BARRY COMPANY 1916 COPYRIGHT BY ZEPHYRIN ENGELHARDT is m TO ST. ANTHONY OF PADUA In a work of this kind, notwithstanding scrupu- lous care, it is scarcely possible to avoid all mistakes. It is hoped, however, that errors may not be so nu- merous nor so important as to cause difficulties. -

The Soviet Critique of a Liberator's

THE SOVIET CRITIQUE OF A LIBERATOR’S ART AND A POET’S OUTCRY: ZINOVII TOLKACHEV, PAVEL ANTOKOL’SKII AND THE ANTI-COSMOPOLITAN PERSECUTIONS OF THE LATE STALINIST PERIOD by ERIC D. BENJAMINSON A THESIS Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts March 2018 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Eric D. Benjaminson Title: The Soviet Critique of a Liberator’s Art and a Poet’s Outcry: Zinovii Tolkachev, Pavel Antokol’skii and the Anti-Cosmopolitan Persecutions of the Late Stalinist Period This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of History by: Julie Hessler Chairperson John McCole Member David Frank Member and Sara D. Hodges Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded: March 2018 ii © 2018 Eric D. Benjaminson iii THESIS ABSTRACT Eric D. Benjaminson Master of Arts Department of History March 2018 Title: The Soviet Critique of a Liberator’s Art and a Poet’s Outcry: Zinovii Tolkachev, Pavel Antokol’skii and the Anti-Cosmopolitan Persecutions of the Late Stalinist Period This thesis investigates Stalin’s post-WW2 anti-cosmopolitan campaign by comparing the lives of two Soviet-Jewish artists. Zinovii Tolkachev was a Ukrainian artist and Pavel Antokol’skii a Moscow poetry professor. Tolkachev drew both Jewish and Socialist themes, while Antokol’skii created no Jewish motifs until his son was killed in combat and he encountered Nazi concentration camps; Tolkachev was at the liberation of Majdanek and Auschwitz. -

San Diego County Historical Treasures

SAN DIEGO COUNTY Campo Stone Store Whaley House Wilderness Gardens HISTORICAL Vallecito Stage Station the county courthouse for a while, and it even served as a Wilderness Gardens (Sickler Mill) County Rd. S2 billiard hall, ballroom, and general store. As if that weren't 14209 Highway 76 TREASURES P.O. Box 502 enough history for one building, it has a reputation as one of the Pala, CA 92059 most haunted houses in the nation; sightings number about a Julian, CA 92036 760-742-1631 half-dozen ghosts, including one of a dog. The interior is being 760-765-1188 elegantly restored to its 1850s appearance. In 1881 the Sickler brothers built a grist mill along the San Luis Rey River to process grain for the area’s farmers. The stone One of the most welcome sights to 19th-century passen- Tours of the house are available. Visit the gift shop in the wheels for the 30-foot-tall mill were made in France and took six gers on the arduous journey across the Colorado Desert restored 1869 Victorian cottage. There are also several other months to make the journey. The mill was the first of its kind in was the Vallecito Stage Station. Today, a 1934 restoration notable historic buildings in the Whaley Complex. of that sod building reminds us of the perils of travel in northern San Diego County. When look at the rock foundation those times. The building also served as an important stop California State Historic Landmark. and iron wheel that remain from the original structure, you can on the “Jackass” mail line and the southern emigrant caravans. -

Cultural Resources Survey of the Melrose Drive Extension

Archaeological and Historical Resources Survey and Evaluation for the Melrose Drive Extension Project, Oceanside, California Prepared for: Seán Cárdenas, RPA Senior Project Manager HELIX Environmental Planning, Inc. 7578 El Cajon Boulevard, Suite 200 La Mesa, California 91941 Prepared by: Susan M. Hector, Ph.D. Principal Investigator Sinéad Ní Ghabhláin, Ph.D. Senior Archaeologist And Michelle Dalope Associate Archaeologist December 2009 2034 Corte Del Nogal Carlsbad, California 92011 (760) 804-5757 ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL RESOURCES SURVEY AND EVALUATION FOR THE MELROSE DRIVE EXTENSION PROJECT, OCEANSIDE, CALIFORNIA Submitted to: Seán Cárdenas, RPA Senior Project Manager HELIX Environmental Planning, Inc. 7578 El Cajon Boulevard, Suite 200 La Mesa, California 91941 Prepared by: Susan M. Hector, Ph.D. Principal Investigator Sinéad Ní Ghabhláin, Ph.D. Senior Archaeologist Michelle Dalope Associate Archaeologist ASM Affiliates, Inc. 2034 Corte Del Nogal Carlsbad, California 92011 December 2009 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................... 1 2. PROJECT AREA BACKGROUND ................................................... 5 ENVIRONMENT .................................................................................... 5 PREHISTORIC CULTURAL SEQUENCE .................................................... 6 Terminological Framework ..................................................................... 6 Human Occupation Prior to 11,500 B.P. ................................................... -

The Journal of San Diego History

Volume 51 Winter/Spring 2005 Numbers 1 and 2 • The Journal of San Diego History The Jour na l of San Diego History SD JouranalCover.indd 1 2/24/06 1:33:24 PM Publication of The Journal of San Diego History has been partially funded by a generous grant from Quest for Truth Foundation of Seattle, Washington, established by the late James G. Scripps; and Peter Janopaul, Anthony Block and their family of companies, working together to preserve San Diego’s history and architectural heritage. Publication of this issue of The Journal of San Diego History has been supported by a grant from “The Journal of San Diego History Fund” of the San Diego Foundation. The San Diego Historical Society is able to share the resources of four museums and its extensive collections with the community through the generous support of the following: City of San Diego Commission for Art and Culture; County of San Diego; foundation and government grants; individual and corporate memberships; corporate sponsorship and donation bequests; sales from museum stores and reproduction prints from the Booth Historical Photograph Archives; admissions; and proceeds from fund-raising events. Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. The paper in the publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Science-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Front cover: Detail from ©SDHS 1998:40 Anne Bricknell/F. E. Patterson Photograph Collection. Back cover: Fallen statue of Swiss Scientist Louis Agassiz, Stanford University, April 1906. -

COUNTERTERRORISM CENTER COUNTERTERRORISM 20-27 MARCH 2019 SPOTLIGHT DIGEST FBI Most Wanted Terrorist: Sajid Mir the Counterterrorism Digest Is a Compilation of |

UNCLASSIFIED US NATIONAL COUNTERTERRORISM CENTER COUNTERTERRORISM 20-27 MARCH 2019 SPOTLIGHT DIGEST FBI Most Wanted Terrorist: Sajid Mir The Counterterrorism Digest is a compilation of | UNCLASSIFIED open source publicly available press An Analysis of Suspected Christchurch, New Zealand, Attacker’s Manifesto 3 material, to include relevant commentary on issues related to terrorism and counterterrorism over the past seven days. It is produced every Wednesday, excluding holidays. The Counterterrorism Digest ON POINT contains situational awareness items detailing 1 ILLINOIS: Woman Pleads Guilty to Conspiring to Provide Material Support to on-going terrorism-related developments which may | Terrorism be of interest to security personnel. Comments and 7 2 NORTH CAROLINA: Man Found Guilty of Attempting to Support ISIS requests for information pertaining to articles featured in 3 CALIFORNIA: Mosque Targeted in Homage to Christchurch, New Zealand, Counterterrorism Digest may be directed to nctcpao@ Attack nctc.gov. 4 UNITED STATES: Department of State (DOS) Amends ISIS Terrorist Designation 5 WORLDWIDE: Al-Qa‘ida Leadership Calls to Avenge New Zealand Shootings Information contained in the Counterterrorism Digest 6 WORLDWIDE: Al-Qa‘ida Ideologue Analyzes Writings on New Zealand is subject to change as a situation further develops. Shooter’s Weapon The inclusion of a report in Counterterrorism Digest is 7 WORLDWIDE: ISIS Releases Al-Naba 174, Urges Reprisals for New Zealand not confirmation of its credibility nor does it imply the Attacks official -

Restoration of a San Diego Landmark Casa De Bandini, Lot 1, Block 451

1 Restoration of a San Diego Landmark BY VICTOR A. WALSH Casa de Bandini, Lot 1, Block 451, 2600 Calhoun Street, Old Town SHP [California Historical Landmark #72, (1932); listed on National Register of Historic Places (Sept. 3, 1971) as a contributing building] From the far side of the old plaza, the two-story, colonnaded stucco building stands in the soft morning light—a sentinel to history. Originally built 1827-1829 by Don Juan Bandini as a family residence and later converted into a hotel, boarding house, olive pickling factory, and tourist hotel and restaurant, the Casa de Bandini is one of the most significant historic buildings in the state.1 In April 2007, California State Parks and the new concessionaire, Delaware North & Co., embarked on a multi-million dollar rehabilitation and restoration of this historic landmark to return it to its appearance as the Cosmopolitan Hotel of the early 1870s. This is an unprecedented historic restoration, perhaps the most important one currently in progress in California. Few other buildings in the state rival the building’s scale or size (over 10,000 square feet) and blending of 19th-century Mexican adobe and American wood-framing construction techniques. It boasts a rich and storied history—a history that is buried in the material fabric and written and oral accounts left behind by previous generations. The Casa and the Don Bandini would become one of the most prominent men of his day in California. Born and educated in Lima, Peru and the son of a Spanish master trader, he arrived in San Diego around 1822.2 In 1827, Governor José María Echeandia granted him and, José Antonio Estudillo, his future father-in-law, adjoining house lots on the plaza, measuring “…100 varas square (or 277.5 x 277.5’) in common,….”3 Through his marriage to Dolores Estudillo and, after her death in 1833, to Refugio Argüello, the daughter of another influential Spanish Californio family, Bandini carved out an illustrious career as a politician, civic leader, and rancher. -

Hispanic-Americans and the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)

Southern Methodist University SMU Scholar History Theses and Dissertations History Spring 2020 INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) Carlos Nava [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_history_etds Recommended Citation Nava, Carlos, "INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939)" (2020). History Theses and Dissertations. 11. https://scholar.smu.edu/hum_sci_history_etds/11 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) Approved by: ______________________________________ Prof. Neil Foley Professor of History ___________________________________ Prof. John R. Chávez Professor of History ___________________________________ Prof. Crista J. DeLuzio Associate Professor of History INTERNATIONALISM IN THE BARRIOS: HISPANIC-AMERICANS AND THE SPANISH CIVIL WAR (1936-1939) A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of Dedman College Southern Methodist University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in History by Carlos Nava B.A. Southern Methodist University May 16, 2020 Nava, Carlos B.A., Southern Methodist University Internationalism in the Barrios: Hispanic-Americans in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) Advisor: Professor Neil Foley Master of Art Conferred May 16, 2020 Thesis Completed February 20, 2020 The ripples of the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) had a far-reaching effect that touched Spanish speaking people outside of Spain.