GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super Chief – El Capitan See Page 4 for Details

AUGUST- lyerlyer SEPTEMBER 2020 Ready for Boarding! Late 1960s Combined Super Chief – El Capitan see page 4 for details FLYER SALE ENDS 9-30-20 Find a Hobby Shop Near You! Visit walthers.com or call 1-800-487-2467 WELCOME CONTENTS Chill out with cool new products, great deals and WalthersProto Super Chief/El Capitan Pages 4-7 Rolling Along & everything you need for summer projects in this issue! Walthers Flyer First Products Pages 8-10 With two great trains in one, reserve your Late 1960s New from Walthers Pages 11-17 Going Strong! combined Super Chief/El Capitan today! Our next HO National Model Railroad Build-Off Pages 18 & 19 Railroads have a long-standing tradition of getting every last WalthersProto® name train features an authentic mix of mile out of their rolling stock and engines. While railfans of Santa Fe Hi-Level and conventional cars - including a New From Our Partners Pages 20 & 21 the 1960s were looking for the newest second-generation brand-new model, new F7s and more! Perfect for The Bargain Depot Pages 22 & 23 diesels and admiring ever-bigger, more specialized freight operation or collection, complete details start on page 4. Walthers 2021 Reference Book Page 24 cars, a lot of older equipment kept rolling right along. A feature of lumber traffic from the 1960s to early 2000s, HO Scale Pages 25-33, 36-51 Work-a-day locals and wayfreights were no less colorful, the next run of WalthersProto 56' Thrall All-Door Boxcars N Scale Pages 52-57 with a mix of earlier engines and equipment that had are loaded with detail! Check out these layout-ready HO recently been repainted and rebuilt. -

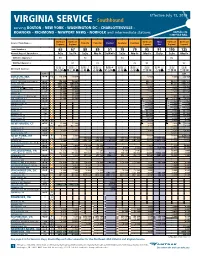

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

40Thanniv Ersary

Spring 2011 • $7 95 FSharing tihe exr periencste of Fastest railways past and present & rsary nive 40th An Things Were Not the Same after May 1, 1971 by George E. Kanary D-Day for Amtrak 5We certainly did not see Turboliners in regular service in Chicago before Amtrak. This train is In mid April, 1971, I was returning from headed for St. Louis in August 1977. —All photos by the author except as noted Seattle, Washington on my favorite train to the Pacific Northwest, the NORTH back into freight service or retire. The what I considered to be an inauspicious COAST LIMITED. For nearly 70 years, friendly stewardess-nurses would find other beginning to the new service. Even the the flagship train of the Northern Pacific employment. The locomotives and cars new name, AMTRAK, was a disappoint - RR, one of the oldest named trains in the would go into the AMTRAK fleet and be ment to me, since I preferred the classier country, had closely followed the route of dispersed country wide, some even winding sounding RAILPAX, which was eliminat - the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804, up running on the other side of the river on ed at nearly the last moment. and was definitely the super scenic way to the Milwaukee Road to the Twin Cities. In addition, wasn’t AMTRAK really Seattle and Portland. My first association That was only one example of the serv - being brought into existence to eliminate with the North Coast Limited dated to ices that would be lost with the advent of the passenger train in America? Didn’t 1948, when I took my first long distance AMTRAK on May 1, 1971. -

Issue of Play on October 4 & 5 at the "The 6 :,53"

I the 'It, 980 6:53 OCTOBER !li AMTRAK... ... now serving BRYAN and LOVELAND ... returns to INDIA,NAPOLIS then turns em away Amtrak's LAKE SHORE LIMITED With appropriate "first trip" is now making regular stops inaugural festivities, Amtrak every day at BRYAN in north introduced daily operation of western Ohio. The westbound its new HOOSIER STATE on the train stops at 11:34am and 1st of October between IND the eastbound train stops at IANAPOLIS and CHICAGO. Sev 8:15pm. eral OARP members were on the Amtrak's SHENANDOAH inaugural trip, including Ray is now stopping daily at a Kline, Dave Marshall and Nick new station stop in suburban Noe. Complimentary champagne Cincinnati. The eastbound was served to all passengers SHENANDOAH stops at LOVELAND and Amtrak public affairs at 7:09pm and the westbound representatives passed out train stops at 8:15am. A m- Amtrak literature. One of trak began both new stops on the Amtrak reps was also pas Sunday, October 26th. Sev sing out OARP brochures! [We eral OARP members were on don't miss an opportunity!] hand at both stations as the Our members reported that the "first trains" rolled in. inaugural round trip was a OARP has supported both new good one, with on-time oper station stops and we are ation the whole way. Tracks glad they have finally come permit 70mph speeds much of about. Both communities are the way and the only rough supportive of their new Am track was noted near Chicago. trak service. How To Find Amtrak held another in its The Station Maps for both series of FAMILY DAYS with BRYAN qnd LOVELAND will be much equipment on public dis fopnd' inside this issue of play on October 4 & 5 at the "the 6 :,53". -

PRIIA Report

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2020 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2020) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2020 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A. -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Regional Rail Service the Vermont Way

DRAFT Regional Rail Service The Vermont Way Authored by Christopher Parker and Carl Fowler November 30, 2017 Contents Contents 2 Executive Summary 4 The Budd Car RDC Advantage 5 Project System Description 6 Routes 6 Schedule 7 Major Employers and Markets 8 Commuter vs. Intercity Designation 10 Project Developer 10 Stakeholders 10 Transportation organizations 10 Town and City Governments 11 Colleges and Universities 11 Resorts 11 Host Railroads 11 Vermont Rail Systems 11 New England Central Railroad 12 Amtrak 12 Possible contract operators 12 Dispatching 13 Liability Insurance 13 Tracks and Right-of-Way 15 Upgraded Track 15 Safety: Grade Crossing Upgrades 15 Proposed Standard 16 Upgrades by segment 16 Cost of Upgrades 17 Safety 19 Platforms and Stations 20 Proposed Stations 20 Existing Stations 22 Construction Methods of New Stations 22 Current and Historical Precedents 25 Rail in Vermont 25 Regional Rail Service in the United States 27 New Mexico 27 Maine 27 Oregon 28 Arizona and Rural New York 28 Rural Massachusetts 28 Executive Summary For more than twenty years various studies have responded to a yearning in Vermont for a regional passenger rail service which would connect Vermont towns and cities. This White Paper, commissioned by Champ P3, LLC reviews the opportunities for and obstacles to delivering rail service at a rural scale appropriate for a rural state. Champ P3 is a mission driven public-private partnership modeled on the Eagle P3 which built Denver’s new commuter rail network. Vermont’s two railroads, Vermont Rail System and Genesee & Wyoming, have experience hosting and operating commuter rail service utilizing Budd cars. -

Amtrak Chicago Area Update

Amtrak Chicago Area Update Amtrak will operate modified schedules for Chicago Hub Services on Tuesday, Jan. 28, following conversations with freight railroads that host Amtrak trains to and from Chicago and in consultation with state transportation departments that sponsor the services. These cancelations are designed to maintain service on most routes while reducing exposure of Amtrak passengers, crews and rail equipment to extreme weather conditions. Passengers are urged to heed the warnings of local officials to use caution making their way to and from stations and to expect delays in bitter cold, gusty winds and blowing snow. A range of tools - including Amtrak.com, smartphone apps and calls to 800-USA-RAIL - are available to assist in travel planning and to provide train status information. The following Amtrak Chicago Hub Services will not be available on Tuesday, Jan. 28: Lincoln Service Trains 300, 301, 306 & 307 are canceled. (Trains 302, 303, 304 & 305 and Trains 21/321 & 22/322 will maintain service on the Chicago-St. Louis corridor) Hiawatha Service Trains 329, 332, 333, 336, 337 & 340 are canceled. (Trains 330, 331, 334, 335, 338, 339, 341 & 342 will maintain service on the Chicago-Milwaukee corridor) Wolverine Service Trains 350 & 355 are canceled. (Trains 351, 352, 353 & 354 will maintain service on the Chicago-Ann Arbor-Detroit/Pontiac corridor) Illinois Zephyr & Carl Sandburg Trains 380 & 381 are canceled. (Amtrak is awaiting word from BNSF Railway Co. regarding service by Trains 382 & 383 on the Chicago-Galesburg-Quincy corridor on Tuesday, Jan. 28. The route was closed by BNSF late Sunday night, leading Trains 380, 381, 382 & 383 to be canceled on Monday, Jan. -

Municipal Security Disclosure

MUNICIPAL SECURITY DISCLOSURE FOR THE FISCAL YEAR ENDED SEPTEMBER 30, 2019 For the City of Miami Beach, Florida and The Miami Beach Redevelopment Agency (A Component Unit of the City of Miami Beach, Florida) MUNICIPAL SECURITY DISCLOSURE City of Miami Beach, Florida For the Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2019 Prepared by: The City of Miami Beach Finance Department 1700 Convention Center Drive, Miami Beach, Florida • 33139 Tel: (305) 673 – 7466 • Fax: (305) 673 – 7795 Last updated July 13, 2020 City of Miami Beach, Florida Report of Annual Financial Information For Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2019 This Report of Annual Financial Information is being filed with the Electronic Municipal Market Access (EMMA), a service of the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board (MSRB). The following is a list of all outstanding bonds and other obligations for the City of Miami Beach at September 30, 2019, in accordance with provisions regarding continuing disclosure set forth in: Outstanding Bonds Original Description Resolution Resolution Commitment Amount Number Date Date $22,500,000 Gulf Breeze Fixed Rate Loan, Series 1985E No. 2001-24500 June 26, 2001 August 1, 2001 (used to repay a portion of the outstanding principal from the Sunshine State Loan and renovation and improvement of two City owned golf courses and their related facilities), (“2001 Gulf Breeze Loan”) $62,465,000 General Obligation Bonds, Series 2003 (used No. 2003-25240 June 11, 2003 July 22, 2003 to improve neighborhood infrastructure in the City, consisting of streetscape and traffic calming measures, shoreline stabilization, Fire Safety Projects and Beaches Projects) (Note: The outstanding balance on the above City of Miami Beach, General Obligation Bonds, Series 2003 were fully refunded by the Series 2019 bonds at September 30, 2019.) $13,590,000 Water and Sewer Revenue Refunding Bonds, No. -

March 25, 2019 Volume 39

MARCH 25, 2019 ■■■■■■■■■■■ VOLUME 39 ■■■■■■■■■■ NUMBER 3 13 The Semaphore 17 David N. Clinton, Editor-in-Chief CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Southeastern Massachusetts…………………. Paul Cutler, Jr. “The Operator”………………………………… Paul Cutler III Cape Cod News………………………………….Skip Burton Boston Herald Reporter……………………… Jim South 24 Boston Globe & Wall Street Journal Reporters Paul Bonanno, Jack Foley Western Massachusetts………………………. Ron Clough Rhode Island News…………………………… Tony Donatelli “The Chief’s Corner”……………………… . Fred Lockhart Mid-Atlantic News……………………………. Doug Buchanan PRODUCTION STAFF Publication…………….………………… …. … Al Taylor Al Munn Jim Ferris Bryan Miller Web Page …………………..………………… Savery Moore Club Photographer……………………………. Joe Dumas The Semaphore is the monthly (except July) newsletter of the South Shore Model Railway Club & Museum (SSMRC) and any opinions found herein are those of the authors thereof and of the Editors and do not necessarily reflect any policies of this organization. The SSMRC, as a non-profit organization, does not endorse any position. Your comments are welcome! Please address all correspondence regarding this publication to: The Semaphore, 11 Hancock Rd., Hingham, MA 02043. ©2019 E-mail: [email protected] Club phone: 781-740-2000. Web page: www.ssmrc.org VOLUME 39 ■■■■■ NUMBER 3 ■■■■■ MARCH 2019 CLUB OFFICERS BILL OF LADING President………………….Jack Foley Vice-President…….. …..Dan Peterson Treasurer………………....Will Baker Book Review ........ ………12 Secretary……………….....Dave Clinton Chief’s Corner ...... ……. .3 Chief Engineer……….. .Fred Lockhart Contests ................ ……….3 Directors……………… ...Bill Garvey (’20) ……………………….. .Bryan Miller (‘20) Clinic……………..………3 ……………………… ….Roger St. Peter (’19) Editor’s Notes. ….….....….12 …………………………...Gary Mangelinkx (‘19) Members ............... …….....12 Memories .............. ………..4 th Potpourri ............... ..…..…..5 ON THE COVER: March 9-10 Show Running Extra....... .….……13 and Open House memories. (Photos by Joe Dumas) 2 FORM 19 ORDERS Fred Lockhart MARCH B.O.D. -

Crescent Corridor Update

Crescent Corridor Update December 21st, 2016 US DOT Talking Freight Norfolk Southern Government Relations Norfolk Southern’s Network • NS operates approximately 20,000 route miles throughout 22 states and the District of Columbia • Engaged in the rail transportation of raw materials, intermediate products, and finished goods • Operates the most extensive intermodal network in the East and is a major transporter of coal and industrial products. • NYSE: NSC 2 NS Intermodal Network Growth Majority of growth has been over Corridors • Norfolk Southern has A Network of Key Corridors employed a “Corridor Albany Boston Detroit Strategy” focusing on four Bethlehem Chicago New York/New Jersey Harrisburg Philadelphia key principles: Columbus Greencastle • Market access Cincinnati • Length of haul Charlotte Memphis • Asset utilization Atlanta Birmingham • Productivity Shreveport New Orleans What is an Intermodal Facility? Intermodal Facility –A rail terminal for transferring freight from one transportation mode to another, either from truck‐to‐rail or rail‐to‐truck for the Crescent Corridor, without the handling of the freight itself when changing modes. NS’ Intermodal Network Norfolk Southern System Intermodal Terminal(s) Market Expansions thru 2010 Market Expansions thru 2012 IM Port Terminal TCS Terminals Total U.S. Intermodal Units (Originated Units) 16,000,000 14,000,000 12,000,000 10,000,000 8,000,000 6,000,000 4,000,000 2,000,000 0 *2016 is Jan-Nov annualized Source: AAR Crescent Corridor Pre-Project Influences • Norfolk Southern – Continued cooperation with long-haul truck carriers – Increase in freight trade between Northeast and South – Infrastructure enhancements for speed and capacity • Key Drivers for Private, Local, State, and Federal Partners – Increased highway congestion and vehicular emissions – Growing vehicle travel miles and congestion on I-81, I- 40, I-85, I-20, and I-76. -

Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations

Pursuant to Section 207 of the Passenger Rail Investment and Improvement Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-432, Division B): Quarterly Report on the Performance and Service Quality of Intercity Passenger Train Operations Covering the Quarter Ended June, 2019 (Third Quarter of Fiscal Year 2019) Federal Railroad Administration United States Department of Transportation Published August 2019 Table of Contents (Notes follow on the next page.) Financial Table 1 (A/B): Short-Term Avoidable Operating Costs (Note 1) Table 2 (A/B): Fully Allocated Operating Cost covered by Passenger-Related Revenue Table 3 (A/B): Long-Term Avoidable Operating Loss (Note 1) Table 4 (A/B): Adjusted Loss per Passenger- Mile Table 5: Passenger-Miles per Train-Mile On-Time Performance (Table 6) Test No. 1 Change in Effective Speed Test No. 2 Endpoint OTP Test No. 3 All-Stations OTP Train Delays Train Delays - Off NEC Table 7: Off-NEC Host Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Table 8: Off-NEC Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Train Delays - On NEC Table 9: On-NEC Total Host and Amtrak Responsible Delays per 10,000 Train-Miles Other Service Quality Table 10: Customer Satisfaction Indicator (eCSI) Scores Table 11: Service Interruptions per 10,000 Train-Miles due to Equipment-related Problems Table 12: Complaints Received Table 13: Food-related Complaints Table 14: Personnel-related Complaints Table 15: Equipment-related Complaints Table 16: Station-related Complaints Public Benefits (Table 17) Connectivity Measure Availability of Other Modes Reference Materials Table 18: Route Descriptions Terminology & Definitions Table 19: Delay Code Definitions Table 20: Host Railroad Code Definitions Appendixes A.