Ultraconserved Elements in the Human Genome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HNRPH1 (HNRNPH1) (NM 005520) Human Tagged ORF Clone Product Data

OriGene Technologies, Inc. 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200 Rockville, MD 20850, US Phone: +1-888-267-4436 [email protected] EU: [email protected] CN: [email protected] Product datasheet for RC201834 HNRPH1 (HNRNPH1) (NM_005520) Human Tagged ORF Clone Product data: Product Type: Expression Plasmids Product Name: HNRPH1 (HNRNPH1) (NM_005520) Human Tagged ORF Clone Tag: Myc-DDK Symbol: HNRNPH1 Synonyms: hnRNPH; HNRPH; HNRPH1 Vector: pCMV6-Entry (PS100001) E. coli Selection: Kanamycin (25 ug/mL) Cell Selection: Neomycin This product is to be used for laboratory only. Not for diagnostic or therapeutic use. View online » ©2021 OriGene Technologies, Inc., 9620 Medical Center Drive, Ste 200, Rockville, MD 20850, US 1 / 6 HNRPH1 (HNRNPH1) (NM_005520) Human Tagged ORF Clone – RC201834 ORF Nucleotide >RC201834 ORF sequence Sequence: Red=Cloning site Blue=ORF Green=Tags(s) TTTTGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCGGCCGGGAATTCGTCGACTGGATCCGGTACCGAGGAGATCTGCC GCCGCGATCGCC ATGATGTTGGGCACGGAAGGTGGAGAGGGATTCGTGGTGAAGGTCCGGGGCTTGCCCTGGTCTTGCTCGG CCGATGAAGTGCAGAGGTTTTTTTCTGACTGCAAAATTCAAAATGGGGCTCAAGGTATTCGTTTCATCTA CACCAGAGAAGGCAGACCAAGTGGCGAGGCTTTTGTTGAACTTGAATCAGAAGATGAAGTCAAATTGGCC CTGAAAAAAGACAGAGAAACTATGGGACACAGATATGTTGAAGTATTCAAGTCAAACAACGTTGAAATGG ATTGGGTGTTGAAGCATACTGGTCCAAATAGTCCTGACACGGCCAATGATGGCTTTGTACGGCTTAGAGG ACTTCCCTTTGGATGTAGCAAGGAAGAAATTGTTCAGTTCTTCTCAGGGTTGGAAATCGTGCCAAATGGG ATAACATTGCCGGTGGACTTCCAGGGGAGGAGTACGGGGGAGGCCTTCGTGCAGTTTGCTTCACAGGAAA TAGCTGAAAAGGCTCTAAAGAAACACAAGGAAAGAATAGGGCACAGGTATATTGAAATCTTTAAGAGCAG TAGAGCTGAAGTTAGAACTCATTATGATCCACCACGAAAGCTTATGGCCATGCAGCGGCCAGGTCCTTAT -

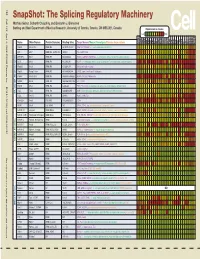

Snapshot: the Splicing Regulatory Machinery Mathieu Gabut, Sidharth Chaudhry, and Benjamin J

192 Cell SnapShot: The Splicing Regulatory Machinery Mathieu Gabut, Sidharth Chaudhry, and Benjamin J. Blencowe 133 Banting and Best Department of Medical Research, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 3E1, Canada Expression in mouse , April4, 2008©2008Elsevier Inc. Low High Name Other Names Protein Domains Binding Sites Target Genes/Mouse Phenotypes/Disease Associations Amy Ceb Hip Hyp OB Eye SC BM Bo Ht SM Epd Kd Liv Lu Pan Pla Pro Sto Spl Thy Thd Te Ut Ov E6.5 E8.5 E10.5 SRp20 Sfrs3, X16 RRM, RS GCUCCUCUUC SRp20, CT/CGRP; −/− early embryonic lethal E3.5 9G8 Sfrs7 RRM, RS, C2HC Znf (GAC)n Tau, GnRH, 9G8 ASF/SF2 Sfrs1 RRM, RS RGAAGAAC HipK3, CaMKIIδ, HIV RNAs; −/− embryonic lethal, cond. KO cardiomyopathy SC35 Sfrs2 RRM, RS UGCUGUU AChE; −/− embryonic lethal, cond. KO deficient T-cell maturation, cardiomyopathy; LS SRp30c Sfrs9 RRM, RS CUGGAUU Glucocorticoid receptor SRp38 Fusip1, Nssr RRM, RS ACAAAGACAA CREB, type II and type XI collagens SRp40 Sfrs5, HRS RRM, RS AGGAGAAGGGA HipK3, PKCβ-II, Fibronectin SRp55 Sfrs6 RRM, RS GGCAGCACCUG cTnT, CD44 DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.010 SRp75 Sfrs4 RRM, RS GAAGGA FN1, E1A, CD45; overexpression enhances chondrogenic differentiation Tra2α Tra2a RRM, RS GAAARGARR GnRH; overexpression promotes RA-induced neural differentiation SR and SR-Related Proteins Tra2β Sfrs10 RRM, RS (GAA)n HipK3, SMN, Tau SRm160 Srrm1 RS, PWI AUGAAGAGGA CD44 SWAP Sfrs8 RS, SWAP ND SWAP, CD45, Tau; possible asthma susceptibility gene hnRNP A1 Hnrnpa1 RRM, RGG UAGGGA/U HipK3, SMN2, c-H-ras; rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus -

Genetic and Pharmacological Approaches to Preventing Neurodegeneration

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Genetic and Pharmacological Approaches to Preventing Neurodegeneration Marco Boccitto University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Neuroscience and Neurobiology Commons Recommended Citation Boccitto, Marco, "Genetic and Pharmacological Approaches to Preventing Neurodegeneration" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 494. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/494 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/494 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Genetic and Pharmacological Approaches to Preventing Neurodegeneration Abstract The Insulin/Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 Signaling (IIS) pathway was first identified as a major modifier of aging in C.elegans. It has since become clear that the ability of this pathway to modify aging is phylogenetically conserved. Aging is a major risk factor for a variety of neurodegenerative diseases including the motor neuron disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). This raises the possibility that the IIS pathway might have therapeutic potential to modify the disease progression of ALS. In a C. elegans model of ALS we found that decreased IIS had a beneficial effect on ALS pathology in this model. This beneficial effect was dependent on activation of the transcription factor daf-16. To further validate IIS as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of ALS, manipulations of IIS in mammalian cells were investigated for neuroprotective activity. Genetic manipulations that increase the activity of the mammalian ortholog of daf-16, FOXO3, were found to be neuroprotective in a series of in vitro models of ALS toxicity. -

Aneuploidy: Using Genetic Instability to Preserve a Haploid Genome?

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science (Cancer Biology) Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Submitted by: Ramona Ramdath In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science Examination Committee Signature/Date Major Advisor: David Allison, M.D., Ph.D. Academic James Trempe, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: David Giovanucci, Ph.D. Randall Ruch, Ph.D. Ronald Mellgren, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: April 10, 2009 Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Ramona Ramdath University of Toledo, Health Science Campus 2009 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandfather who died of lung cancer two years ago, but who always instilled in us the value and importance of education. And to my mom and sister, both of whom have been pillars of support and stimulating conversations. To my sister, Rehanna, especially- I hope this inspires you to achieve all that you want to in life, academically and otherwise. ii Acknowledgements As we go through these academic journeys, there are so many along the way that make an impact not only on our work, but on our lives as well, and I would like to say a heartfelt thank you to all of those people: My Committee members- Dr. James Trempe, Dr. David Giovanucchi, Dr. Ronald Mellgren and Dr. Randall Ruch for their guidance, suggestions, support and confidence in me. My major advisor- Dr. David Allison, for his constructive criticism and positive reinforcement. -

A Novel Resveratrol Analog: Its Cell Cycle Inhibitory, Pro-Apoptotic and Anti-Inflammatory Activities on Human Tumor Cells

A NOVEL RESVERATROL ANALOG : ITS CELL CYCLE INHIBITORY, PRO-APOPTOTIC AND ANTI-INFLAMMATORY ACTIVITIES ON HUMAN TUMOR CELLS A dissertation submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Boren Lin May 2006 Dissertation written by Boren Lin B.S., Tunghai University, 1996 M.S., Kent State University, 2003 Ph. D., Kent State University, 2006 Approved by Dr. Chun-che Tsai , Chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Bryan R. G. Williams , Co-chair, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. Johnnie W. Baker , Members, Doctoral Dissertation Committee Dr. James L. Blank , Dr. Bansidhar Datta , Dr. Gail C. Fraizer , Accepted by Dr. Robert V. Dorman , Director, School of Biomedical Sciences Dr. John R. Stalvey , Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………….………v LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………….vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS….………………………………………………………….viii I INTRODUCTION….………………………………………………….1 Background and Significance……………………………………………………..1 Specific Aims………………………………………………………………………12 II MATERIALS AND METHODS.…………………………………………….16 Cell Culture and Compounds…….……………….…………………………….….16 MTT Cell Viability Assay………………………………………………………….16 Trypan Blue Exclusive Assay……………………………………………………...18 Flow Cytometry for Cell Cycle Analysis……………..……………....……………19 DNA Fragmentation Assay……………………………………………...…………23 Caspase-3 Activity Assay………………………………...……….….…….………24 Annexin V-FITC Staining Assay…………………………………..…...….………28 NF-kappa B p65 Activity Assay……………………………………..………….…29 -

Gene Expression During Normal and FSHD Myogenesis Tsumagari Et Al

Gene expression during normal and FSHD myogenesis Tsumagari et al. Tsumagari et al. BMC Medical Genomics 2011, 4:67 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1755-8794/4/67 (27 September 2011) Tsumagari et al. BMC Medical Genomics 2011, 4:67 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1755-8794/4/67 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Gene expression during normal and FSHD myogenesis Koji Tsumagari1, Shao-Chi Chang1, Michelle Lacey2,3, Carl Baribault2,3, Sridar V Chittur4, Janet Sowden5, Rabi Tawil5, Gregory E Crawford6 and Melanie Ehrlich1,3* Abstract Background: Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy (FSHD) is a dominant disease linked to contraction of an array of tandem 3.3-kb repeats (D4Z4) at 4q35. Within each repeat unit is a gene, DUX4, that can encode a protein containing two homeodomains. A DUX4 transcript derived from the last repeat unit in a contracted array is associated with pathogenesis but it is unclear how. Methods: Using exon-based microarrays, the expression profiles of myogenic precursor cells were determined. Both undifferentiated myoblasts and myoblasts differentiated to myotubes derived from FSHD patients and controls were studied after immunocytochemical verification of the quality of the cultures. To further our understanding of FSHD and normal myogenesis, the expression profiles obtained were compared to those of 19 non-muscle cell types analyzed by identical methods. Results: Many of the ~17,000 examined genes were differentially expressed (> 2-fold, p < 0.01) in control myoblasts or myotubes vs. non-muscle cells (2185 and 3006, respectively) or in FSHD vs. control myoblasts or myotubes (295 and 797, respectively). Surprisingly, despite the morphologically normal differentiation of FSHD myoblasts to myotubes, most of the disease-related dysregulation was seen as dampening of normal myogenesis- specific expression changes, including in genes for muscle structure, mitochondrial function, stress responses, and signal transduction. -

Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes in Human Bladder Cancer Through Genome-Wide Gene Expression Profiling

521-531 24/7/06 18:28 Page 521 ONCOLOGY REPORTS 16: 521-531, 2006 521 Identification of differentially expressed genes in human bladder cancer through genome-wide gene expression profiling KAZUMORI KAWAKAMI1,3, HIDEKI ENOKIDA1, TOKUSHI TACHIWADA1, TAKENARI GOTANDA1, KENGO TSUNEYOSHI1, HIROYUKI KUBO1, KENRYU NISHIYAMA1, MASAKI TAKIGUCHI2, MASAYUKI NAKAGAWA1 and NAOHIKO SEKI3 1Department of Urology, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Kagoshima University, 8-35-1 Sakuragaoka, Kagoshima 890-8520; Departments of 2Biochemistry and Genetics, and 3Functional Genomics, Graduate School of Medicine, Chiba University, 1-8-1 Inohana, Chuo-ku, Chiba 260-8670, Japan Received February 15, 2006; Accepted April 27, 2006 Abstract. Large-scale gene expression profiling is an effective CKS2 gene not only as a potential biomarker for diagnosing, strategy for understanding the progression of bladder cancer but also for staging human BC. This is the first report (BC). The aim of this study was to identify genes that are demonstrating that CKS2 expression is strongly correlated expressed differently in the course of BC progression and to with the progression of human BC. establish new biomarkers for BC. Specimens from 21 patients with pathologically confirmed superficial (n=10) or Introduction invasive (n=11) BC and 4 normal bladder samples were studied; samples from 14 of the 21 BC samples were subjected Bladder cancer (BC) is among the 5 most common to microarray analysis. The validity of the microarray results malignancies worldwide, and the 2nd most common tumor of was verified by real-time RT-PCR. Of the 136 up-regulated the genitourinary tract and the 2nd most common cause of genes we detected, 21 were present in all 14 BCs examined death in patients with cancer of the urinary tract (1-7). -

Mouse Srsf7 Knockout Project (CRISPR/Cas9)

https://www.alphaknockout.com Mouse Srsf7 Knockout Project (CRISPR/Cas9) Objective: To create a Srsf7 knockout Mouse model (C57BL/6J) by CRISPR/Cas-mediated genome engineering. Strategy summary: The Srsf7 gene (NCBI Reference Sequence: NM_146083.2 ; Ensembl: ENSMUSG00000024097 ) is located on Mouse chromosome 17. 8 exons are identified, with the ATG start codon in exon 1 and the TGA stop codon in exon 8 (Transcript: ENSMUST00000063417). Exon 3~8 will be selected as target site. Cas9 and gRNA will be co-injected into fertilized eggs for KO Mouse production. The pups will be genotyped by PCR followed by sequencing analysis. Note: Exon 3 starts from about 29.41% of the coding region. Exon 3~8 covers 70.73% of the coding region. The size of effective KO region: ~3889 bp. The KO region does not have any other known gene. Page 1 of 9 https://www.alphaknockout.com Overview of the Targeting Strategy Wildtype allele 5' gRNA region gRNA region 3' 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Legends Exon of mouse Srsf7 Knockout region Page 2 of 9 https://www.alphaknockout.com Overview of the Dot Plot (up) Window size: 15 bp Forward Reverse Complement Sequence 12 Note: The 2000 bp section upstream of Exon 3 is aligned with itself to determine if there are tandem repeats. No significant tandem repeat is found in the dot plot matrix. So this region is suitable for PCR screening or sequencing analysis. Overview of the Dot Plot (down) Window size: 15 bp Forward Reverse Complement Sequence 12 Note: The 2000 bp section downstream of stop codon is aligned with itself to determine if there are tandem repeats. -

Open Data for Differential Network Analysis in Glioma

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Open Data for Differential Network Analysis in Glioma , Claire Jean-Quartier * y , Fleur Jeanquartier y and Andreas Holzinger Holzinger Group HCI-KDD, Institute for Medical Informatics, Statistics and Documentation, Medical University Graz, Auenbruggerplatz 2/V, 8036 Graz, Austria; [email protected] (F.J.); [email protected] (A.H.) * Correspondence: [email protected] These authors contributed equally to this work. y Received: 27 October 2019; Accepted: 3 January 2020; Published: 15 January 2020 Abstract: The complexity of cancer diseases demands bioinformatic techniques and translational research based on big data and personalized medicine. Open data enables researchers to accelerate cancer studies, save resources and foster collaboration. Several tools and programming approaches are available for analyzing data, including annotation, clustering, comparison and extrapolation, merging, enrichment, functional association and statistics. We exploit openly available data via cancer gene expression analysis, we apply refinement as well as enrichment analysis via gene ontology and conclude with graph-based visualization of involved protein interaction networks as a basis for signaling. The different databases allowed for the construction of huge networks or specified ones consisting of high-confidence interactions only. Several genes associated to glioma were isolated via a network analysis from top hub nodes as well as from an outlier analysis. The latter approach highlights a mitogen-activated protein kinase next to a member of histondeacetylases and a protein phosphatase as genes uncommonly associated with glioma. Cluster analysis from top hub nodes lists several identified glioma-associated gene products to function within protein complexes, including epidermal growth factors as well as cell cycle proteins or RAS proto-oncogenes. -

Transcriptional Recapitulation and Subversion Of

Open Access Research2007KaiseretVolume al. 8, Issue 7, Article R131 Transcriptional recapitulation and subversion of embryonic colon comment development by mouse colon tumor models and human colon cancer Sergio Kaiser¤*, Young-Kyu Park¤†, Jeffrey L Franklin†, Richard B Halberg‡, Ming Yu§, Walter J Jessen*, Johannes Freudenberg*, Xiaodi Chen‡, Kevin Haigis¶, Anil G Jegga*, Sue Kong*, Bhuvaneswari Sakthivel*, Huan Xu*, Timothy Reichling¥, Mohammad Azhar#, Gregory P Boivin**, reviews Reade B Roberts§, Anika C Bissahoyo§, Fausto Gonzales††, Greg C Bloom††, Steven Eschrich††, Scott L Carter‡‡, Jeremy E Aronow*, John Kleimeyer*, Michael Kleimeyer*, Vivek Ramaswamy*, Stephen H Settle†, Braden Boone†, Shawn Levy†, Jonathan M Graff§§, Thomas Doetschman#, Joanna Groden¥, William F Dove‡, David W Threadgill§, Timothy J Yeatman††, reports Robert J Coffey Jr† and Bruce J Aronow* Addresses: *Biomedical Informatics, Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH 45229, USA. †Departments of Medicine, and Cell and Developmental Biology, Vanderbilt University and Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Nashville, TN 37232, USA. ‡McArdle Laboratory for Cancer Research, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA. §Department of Genetics and Lineberger Cancer Center, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, USA. ¶Molecular Pathology Unit and Center for Cancer Research, Massachusetts deposited research General Hospital, Charlestown, MA 02129, USA. ¥Division of Human Cancer Genetics, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, Ohio 43210-2207, USA. #Institute for Collaborative BioResearch, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721-0036, USA. **University of Cincinnati, Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Cincinnati, OH 45267, USA. ††H Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Tampa, FL 33612, USA. ‡‡Children's Hospital Informatics Program at the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology (CHIP@HST), Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 1 Name Class Description SU-8 CAN SU-8 Homo sapiens apoptosis related protein APR-4 mRNA, partial cds. AF144054 Apoptosis [AF144054] 3,300 BM023129 ie79h07.x1 Melton Normalized Human Islet 4 N4-HIS 1 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:5673444 3' similar to SW:BUB3_MOUSE Q9WVA3 MITOTIC CHECKPOINT PROTEIN BM023129 Cell cycle BUB3 ;, mRNA sequence [BM023129] 0.332 TAGLN2 Differentiation Homo sapiens transgelin 2 (TAGLN2), mRNA [NM_003564] 3.349 HSPC065 Heat shock Homo sapiens HSPC065 protein (HSPC065), mRNA [NM_014157] 3.102 Homo sapiens chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 19 (CCL19), mRNA CCL19 Ligand [NM_006274] 3.800 THC2045396 Membrane O00429 (O00429) Dynamin-like protein, partial (16%) [THC2045396] 0.131 AW075437 xb23c01.x1 NCI_CGAP_Kid13 Homo sapiens cDNA clone IMAGE:2577120 3' similar to WP:C17G10.8 CE16861 FAT-3: AW075437 Metabolism ALCOHOL DEHYDROGENASE ;, mRNA sequence [AW075437] 0.314 Homo sapiens 3-hydroxyanthranilate 3,4-dioxygenase (HAAO), mRNA HAAO Metabolism [NM_012205] 4.733 3.885 Homo sapiens abhydrolase domain containing 9 (ABHD9), mRNA ABHD9 Metabolism [NM_024794] 3.689 NPEPL1 Metabolism Homo sapiens aminopeptidase-like 1 (NPEPL1), mRNA [NM_024663] 3.837 4.054 Homo sapiens pyridoxine 5'-phosphate oxidase (PNPO), mRNA PNPO Metabolism [NM_018129] 3.978 Homo sapiens solute carrier family 27 (fatty acid transporter), member SLC27A1 Metabolism 1 (SLC27A1), mRNA [NM_198580] 3.066 RIB2_HUMAN (P04844) Dolichyl-diphosphooligosaccharide--protein glycosyltransferase 63 kDa subunit precursor (Ribophorin II) (RPN-II) THC2159243 -

Ultraconserved Elements Are Associated with Homeostatic Control of Splicing Regulators by Alternative Splicing and Nonsense-Mediated Decay

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 24, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Ultraconserved elements are associated with homeostatic control of splicing regulators by alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated decay Julie Z. Ni,1 Leslie Grate,1 John Paul Donohue,1 Christine Preston,2 Naomi Nobida,2 Georgeann O’Brien,2 Lily Shiue,1 Tyson A. Clark,3 John E. Blume,3 and Manuel Ares Jr.1,2,4 1Center for Molecular Biology of RNA and Department of Molecular, Cell, and Developmental Biology, University of California at Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, California 95064, USA; 2Hughes Undergraduate Research Laboratory, University of California at Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, California 95064, USA; 3Affymetrix, Inc., Santa Clara, California 95051, USA Many alternative splicing events create RNAs with premature stop codons, suggesting that alternative splicing coupled with nonsense-mediated decay (AS-NMD) may regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. We tested this idea in mice by blocking NMD and measuring changes in isoform representation using splicing-sensitive microarrays. We found a striking class of highly conserved stop codon-containing exons whose inclusion renders the transcript sensitive to NMD. A genomic search for additional examples identified >50 such exons in genes with a variety of functions. These exons are unusually frequent in genes that encode splicing activators and are unexpectedly enriched in the so-called “ultraconserved” elements in the mammalian lineage. Further analysis show that NMD of mRNAs for splicing activators such as SR proteins is triggered by splicing activation events, whereas NMD of the mRNAs for negatively acting hnRNP proteins is triggered by splicing repression, a polarity consistent with widespread homeostatic control of splicing regulator gene expression.