Gene Expression During Normal and FSHD Myogenesis Tsumagari Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MKL1 (C) Antibody, Rabbit Polyclonal

Order: (888)-282-5810 (Phone) (818)-707-0392 (Fax) [email protected] Web: www.Abiocode.com MKL1 (C) Antibody, Rabbit Polyclonal Cat#: R2403-2 Lot#: Refer to vial Quantity: 100 ul Application: WB Predicted I Observed M.W.: 99 I 140 kDa Uniprot ID: Q969V6 Background: MKL/myocardin-like protein 1 (MKL1) is a transcriptional coactivator of serum response factor (SRF) with the potential to modulate SRF target genes. MKL1 suppresses TNF-induced cell death by inhibiting activation of caspases; its transcriptional activity is indispensable for the antiapoptotic function. MKL1 may up-regulate antiapoptotic molecules, which in turn inhibit caspase activation. Other Names: MKL/myocardin-like protein 1, Megakaryoblastic leukemia 1 protein, Megakaryocytic acute leukemia protein, Myocardin-related transcription factor A, MRTF-A, KIAA1438, MAL Source and Purity: Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were produced by immunizing animals with a GST-fusion protein containing the C-terminal region of human MKL1. Antibodies were purified by affinity purification using immunogen. Storage Buffer and Condition: Supplied in 1 x PBS (pH 7.4), 100 ug/ml BSA, 40% Glycerol, 0.01% NaN3. Store at -20 °C. Stable for 6 months from date of receipt. Species Specificity: Human Tested Applications: WB: 1:1,000-1:3,000 (detect endogenous protein*) *: The apparent protein size on WB may be different from the calculated M.W. due to modifications. For research use only. Not for therapeutic or diagnostic purposes. Abiocode, Inc., 29397 Agoura Rd., Ste 106, Agoura Hills, CA 91301 Order: (888)-282-5810 (Phone) (818)-707-0392 (Fax) [email protected] Web: www.Abiocode.com Product Data: kDa A B 250 150 100 75 50 37 Fig 1. -

List of Genes Associated with Sudden Cardiac Death (Scdgseta) Gene

List of genes associated with sudden cardiac death (SCDgseta) mRNA expression in normal human heart Entrez_I Gene symbol Gene name Uniprot ID Uniprot name fromb D GTEx BioGPS SAGE c d e ATP-binding cassette subfamily B ABCB1 P08183 MDR1_HUMAN 5243 √ √ member 1 ATP-binding cassette subfamily C ABCC9 O60706 ABCC9_HUMAN 10060 √ √ member 9 ACE Angiotensin I–converting enzyme P12821 ACE_HUMAN 1636 √ √ ACE2 Angiotensin I–converting enzyme 2 Q9BYF1 ACE2_HUMAN 59272 √ √ Acetylcholinesterase (Cartwright ACHE P22303 ACES_HUMAN 43 √ √ blood group) ACTC1 Actin, alpha, cardiac muscle 1 P68032 ACTC_HUMAN 70 √ √ ACTN2 Actinin alpha 2 P35609 ACTN2_HUMAN 88 √ √ √ ACTN4 Actinin alpha 4 O43707 ACTN4_HUMAN 81 √ √ √ ADRA2B Adrenoceptor alpha 2B P18089 ADA2B_HUMAN 151 √ √ AGT Angiotensinogen P01019 ANGT_HUMAN 183 √ √ √ AGTR1 Angiotensin II receptor type 1 P30556 AGTR1_HUMAN 185 √ √ AGTR2 Angiotensin II receptor type 2 P50052 AGTR2_HUMAN 186 √ √ AKAP9 A-kinase anchoring protein 9 Q99996 AKAP9_HUMAN 10142 √ √ √ ANK2/ANKB/ANKYRI Ankyrin 2 Q01484 ANK2_HUMAN 287 √ √ √ N B ANKRD1 Ankyrin repeat domain 1 Q15327 ANKR1_HUMAN 27063 √ √ √ ANKRD9 Ankyrin repeat domain 9 Q96BM1 ANKR9_HUMAN 122416 √ √ ARHGAP24 Rho GTPase–activating protein 24 Q8N264 RHG24_HUMAN 83478 √ √ ATPase Na+/K+–transporting ATP1B1 P05026 AT1B1_HUMAN 481 √ √ √ subunit beta 1 ATPase sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic ATP2A2 P16615 AT2A2_HUMAN 488 √ √ √ reticulum Ca2+ transporting 2 AZIN1 Antizyme inhibitor 1 O14977 AZIN1_HUMAN 51582 √ √ √ UDP-GlcNAc: betaGal B3GNT7 beta-1,3-N-acetylglucosaminyltransfe Q8NFL0 -

Searching the Genomes of Inbred Mouse Strains for Incompatibilities That Reproductively Isolate Their Wild Relatives

Journal of Heredity 2007:98(2):115–122 ª The American Genetic Association. 2007. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/jhered/esl064 For permissions, please email: [email protected]. Advance Access publication January 5, 2007 Searching the Genomes of Inbred Mouse Strains for Incompatibilities That Reproductively Isolate Their Wild Relatives BRET A. PAYSEUR AND MICHAEL PLACE From the Laboratory of Genetics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706. Address correspondence to the author at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Identification of the genes that underlie reproductive isolation provides important insights into the process of speciation. According to the Dobzhansky–Muller model, these genes suffer disrupted interactions in hybrids due to independent di- vergence in separate populations. In hybrid populations, natural selection acts to remove the deleterious heterospecific com- binations that cause these functional disruptions. When selection is strong, this process can maintain multilocus associations, primarily between conspecific alleles, providing a signature that can be used to locate incompatibilities. We applied this logic to populations of house mice that were formed by hybridization involving two species that show partial reproductive isolation, Mus domesticus and Mus musculus. Using molecular markers likely to be informative about species ancestry, we scanned the genomes of 1) classical inbred strains and 2) recombinant inbred lines for pairs of loci that showed extreme linkage disequi- libria. By using the same set of markers, we identified a list of locus pairs that displayed similar patterns in both scans. These genomic regions may contain genes that contribute to reproductive isolation between M. domesticus and M. -

Wide-Scale Analysis of Human Functional Transcription Factor

Wide-Scale Analysis of Human Functional Transcription Factor Binding Reveals a Strong Bias towards the Transcription Start Site Yuval Tabach1,2, Ran Brosh2, Yossi Buganim2, Anat Reiner1, Or Zuk1, Assif Yitzhaky1, Mark Koudritsky1, Varda Rotter2 and Eytan Domany1,* 1Departments of Physics of Complex Systems and 2Molecular Cell Biology, The Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 76100, Israel *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Tel: +972-8-9343964 Fax: +972-8- 9344109 Running title: Binding Sites Location Bias Keywords: Transcription factor binding sites, location bias, cell cycle, NF-kB, promoter, Gene Ontology, TATA, myocardin 1 Summary Background: Elucidating basic principles that underlie regulation of gene expression by transcription factors (TFs) is a central challenge of the post-genomic era. Transcription factors regulate expression by binding to specific DNA sequences; such a binding event is functional when it affects gene expression. Functionality of a binding site is reflected in conservation of the binding sequence during evolution and in over represented binding in gene groups with coherent biological functions. Functionality is governed by several parameters such as the TF- DNA binding strength, distance of the binding site from the transcription start site (TSS), DNA packing, and more. Understanding how these parameters control functionality of different TFs in different biological contexts is an essential step towards identifying functional TF binding sites, a must for understanding regulation of transcription. Methodology/Principal Findings: We introduce a novel method to screen the promoters of a set of genes with shared biological function, against a precompiled library of motifs, and find those motifs which are statistically over-represented in the gene set. -

Bioinformatics Analyses of Genomic Imprinting

Bioinformatics Analyses of Genomic Imprinting Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades des Doktors der Naturwissenschaften der Naturwissenschaftlich-Technischen Fakultät III Chemie, Pharmazie, Bio- und Werkstoffwissenschaften der Universität des Saarlandes von Barbara Hutter Saarbrücken 2009 Tag des Kolloquiums: 08.12.2009 Dekan: Prof. Dr.-Ing. Stefan Diebels Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Volkhard Helms Priv.-Doz. Dr. Martina Paulsen Vorsitz: Prof. Dr. Jörn Walter Akad. Mitarbeiter: Dr. Tihamér Geyer Table of contents Summary________________________________________________________________ I Zusammenfassung ________________________________________________________ I Acknowledgements _______________________________________________________II Abbreviations ___________________________________________________________ III Chapter 1 – Introduction __________________________________________________ 1 1.1 Important terms and concepts related to genomic imprinting __________________________ 2 1.2 CpG islands as regulatory elements ______________________________________________ 3 1.3 Differentially methylated regions and imprinting clusters_____________________________ 6 1.4 Reading the imprint __________________________________________________________ 8 1.5 Chromatin marks at imprinted regions___________________________________________ 10 1.6 Roles of repetitive elements ___________________________________________________ 12 1.7 Functional implications of imprinted genes _______________________________________ 14 1.8 Evolution and parental conflict ________________________________________________ -

1 Supporting Information for a Microrna Network Regulates

Supporting Information for A microRNA Network Regulates Expression and Biosynthesis of CFTR and CFTR-ΔF508 Shyam Ramachandrana,b, Philip H. Karpc, Peng Jiangc, Lynda S. Ostedgaardc, Amy E. Walza, John T. Fishere, Shaf Keshavjeeh, Kim A. Lennoxi, Ashley M. Jacobii, Scott D. Rosei, Mark A. Behlkei, Michael J. Welshb,c,d,g, Yi Xingb,c,f, Paul B. McCray Jr.a,b,c Author Affiliations: Department of Pediatricsa, Interdisciplinary Program in Geneticsb, Departments of Internal Medicinec, Molecular Physiology and Biophysicsd, Anatomy and Cell Biologye, Biomedical Engineeringf, Howard Hughes Medical Instituteg, Carver College of Medicine, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA-52242 Division of Thoracic Surgeryh, Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada-M5G 2C4 Integrated DNA Technologiesi, Coralville, IA-52241 To whom correspondence should be addressed: Email: [email protected] (M.J.W.); yi- [email protected] (Y.X.); Email: [email protected] (P.B.M.) This PDF file includes: Materials and Methods References Fig. S1. miR-138 regulates SIN3A in a dose-dependent and site-specific manner. Fig. S2. miR-138 regulates endogenous SIN3A protein expression. Fig. S3. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in Calu-3 cells. Fig. S4. miR-138 regulates endogenous CFTR protein expression in primary human airway epithelia. Fig. S5. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HeLa cells. Fig. S6. miR-138 regulates CFTR expression in HEK293T cells. Fig. S7. HeLa cells exhibit CFTR channel activity. Fig. S8. miR-138 improves CFTR processing. Fig. S9. miR-138 improves CFTR-ΔF508 processing. Fig. S10. SIN3A inhibition yields partial rescue of Cl- transport in CF epithelia. -

Transcriptome and DNA Methylation Analyses of the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying with Longissimus Dorsi Muscles at Different Stages of Development in the Polled Yak

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Transcriptome and DNA Methylation Analyses of the Molecular Mechanisms Underlying with Longissimus dorsi Muscles at Different Stages of Development in the Polled Yak Xiaoming Ma 1,2, Congjun Jia 1,2, Min Chu 1,2, Donghai Fu 1,2 , Qinhui Lei 1,2, Xuezhi Ding 1,2, Xiaoyun Wu 1,2, Xian Guo 1,2, Jie Pei 1,2, Pengjia Bao 1,2, Ping Yan 1,* and Chunnian Liang 2,* 1 Animal Science Department, Lanzhou Institute of Husbandry and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lanzhou 730050, China; [email protected] (X.M.); [email protected] (C.J.); [email protected] (M.C.); [email protected] (D.F.); [email protected] (Q.L.); [email protected] (X.D.); [email protected] (X.W.); [email protected] (X.G.); [email protected] (J.P.); [email protected] (P.B.) 2 Key Laboratory for Yak Genetics, Breeding, and Reproduction Engineering of Gansu Province, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Lanzhou 730050, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (P.Y.); [email protected] (C.L.); Tel.: +86-0931-2115288 (P.Y.); +86-0931-2115271 (C.L.) Received: 29 October 2019; Accepted: 21 November 2019; Published: 26 November 2019 Abstract: DNA methylation modifications are implicated in many biological processes. As the most common epigenetic mechanism DNA methylation also affects muscle growth and development. The majority of previous studies have focused on different varieties of yak, but little is known about the epigenetic regulation mechanisms in different age groups of animals. -

DEAD-Box RNA Helicases in Cell Cycle Control and Clinical Therapy

cells Review DEAD-Box RNA Helicases in Cell Cycle Control and Clinical Therapy Lu Zhang 1,2 and Xiaogang Li 2,3,* 1 Department of Nephrology, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan 430060, China; [email protected] 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, 200 1st Street, SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA 3 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Mayo Clinic, 200 1st Street, SW, Rochester, MN 55905, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-507-266-0110 Abstract: Cell cycle is regulated through numerous signaling pathways that determine whether cells will proliferate, remain quiescent, arrest, or undergo apoptosis. Abnormal cell cycle regula- tion has been linked to many diseases. Thus, there is an urgent need to understand the diverse molecular mechanisms of how the cell cycle is controlled. RNA helicases constitute a large family of proteins with functions in all aspects of RNA metabolism, including unwinding or annealing of RNA molecules to regulate pre-mRNA, rRNA and miRNA processing, clamping protein complexes on RNA, or remodeling ribonucleoprotein complexes, to regulate gene expression. RNA helicases also regulate the activity of specific proteins through direct interaction. Abnormal expression of RNA helicases has been associated with different diseases, including cancer, neurological disorders, aging, and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) via regulation of a diverse range of cellular processes such as cell proliferation, cell cycle arrest, and apoptosis. Recent studies showed that RNA helicases participate in the regulation of the cell cycle progression at each cell cycle phase, including G1-S transition, S phase, G2-M transition, mitosis, and cytokinesis. -

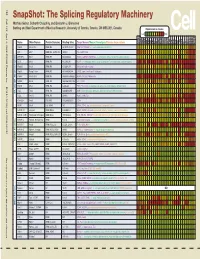

Snapshot: the Splicing Regulatory Machinery Mathieu Gabut, Sidharth Chaudhry, and Benjamin J

192 Cell SnapShot: The Splicing Regulatory Machinery Mathieu Gabut, Sidharth Chaudhry, and Benjamin J. Blencowe 133 Banting and Best Department of Medical Research, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M5S 3E1, Canada Expression in mouse , April4, 2008©2008Elsevier Inc. Low High Name Other Names Protein Domains Binding Sites Target Genes/Mouse Phenotypes/Disease Associations Amy Ceb Hip Hyp OB Eye SC BM Bo Ht SM Epd Kd Liv Lu Pan Pla Pro Sto Spl Thy Thd Te Ut Ov E6.5 E8.5 E10.5 SRp20 Sfrs3, X16 RRM, RS GCUCCUCUUC SRp20, CT/CGRP; −/− early embryonic lethal E3.5 9G8 Sfrs7 RRM, RS, C2HC Znf (GAC)n Tau, GnRH, 9G8 ASF/SF2 Sfrs1 RRM, RS RGAAGAAC HipK3, CaMKIIδ, HIV RNAs; −/− embryonic lethal, cond. KO cardiomyopathy SC35 Sfrs2 RRM, RS UGCUGUU AChE; −/− embryonic lethal, cond. KO deficient T-cell maturation, cardiomyopathy; LS SRp30c Sfrs9 RRM, RS CUGGAUU Glucocorticoid receptor SRp38 Fusip1, Nssr RRM, RS ACAAAGACAA CREB, type II and type XI collagens SRp40 Sfrs5, HRS RRM, RS AGGAGAAGGGA HipK3, PKCβ-II, Fibronectin SRp55 Sfrs6 RRM, RS GGCAGCACCUG cTnT, CD44 DOI 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.010 SRp75 Sfrs4 RRM, RS GAAGGA FN1, E1A, CD45; overexpression enhances chondrogenic differentiation Tra2α Tra2a RRM, RS GAAARGARR GnRH; overexpression promotes RA-induced neural differentiation SR and SR-Related Proteins Tra2β Sfrs10 RRM, RS (GAA)n HipK3, SMN, Tau SRm160 Srrm1 RS, PWI AUGAAGAGGA CD44 SWAP Sfrs8 RS, SWAP ND SWAP, CD45, Tau; possible asthma susceptibility gene hnRNP A1 Hnrnpa1 RRM, RGG UAGGGA/U HipK3, SMN2, c-H-ras; rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus -

Co-Occupancy by Multiple Cardiac Transcription Factors Identifies

Co-occupancy by multiple cardiac transcription factors identifies transcriptional enhancers active in heart Aibin Hea,b,1, Sek Won Konga,b,c,1, Qing Maa,b, and William T. Pua,b,2 aDepartment of Cardiology and cChildren’s Hospital Informatics Program, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA 02115; and bHarvard Stem Cell Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138 Edited by Eric N. Olson, University of Texas Southwestern, Dallas, TX, and approved February 23, 2011 (received for review November 12, 2010) Identification of genomic regions that control tissue-specific gene study of a handful of model genes (e.g., refs. 7–10), it has not been expression is currently problematic. ChIP and high-throughput se- evaluated using unbiased, genome-wide approaches. quencing (ChIP-seq) of enhancer-associated proteins such as p300 In this study, we used a modified ChIP-seq approach to define identifies some but not all enhancers active in a tissue. Here we genome wide the binding sites of these cardiac TFs (1). We show that co-occupancy of a chromatin region by multiple tran- provide unbiased support for collaborative TF interactions in scription factors (TFs) identifies a distinct set of enhancers. GATA- driving cardiac gene expression and use this principle to show that chromatin co-occupancy by multiple TFs identifies enhancers binding protein 4 (GATA4), NK2 transcription factor-related, lo- with cardiac activity in vivo. The majority of these multiple TF- cus 5 (NKX2-5), T-box 5 (TBX5), serum response factor (SRF), and “ binding loci (MTL) enhancers were distinct from p300-bound myocyte-enhancer factor 2A (MEF2A), here referred to as cardiac enhancers in location and functional properties. -

Anti-EIF2C1 / AGO1 Antibody (ARG63916)

Product datasheet [email protected] ARG63916 Package: 100 μg anti-EIF2C1 / AGO1 antibody Store at: -20°C Summary Product Description Goat Polyclonal antibody recognizes EIF2C1 / AGO1 Tested Reactivity Hu Predict Reactivity Ms, Rat, Dog Tested Application IHC-P, WB Specificity This product is not expected to cross-react with EIF2C2, EIF2C3 and EIF2C4. Host Goat Clonality Polyclonal Isotype IgG Target Name EIF2C1 / AGO1 Antigen Species Human Immunogen C-KNASYNLDPYIQEF Conjugation Un-conjugated Alternate Names GERP95; Q99; eIF2C 1; EIF2C; EIF2C1; Argonaute RISC catalytic component 1; Argonaute1; Protein argonaute-1; hAgo1; Putative RNA-binding protein Q99; eIF-2C 1; Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2C 1 Application Instructions Application table Application Dilution IHC-P 2.5 µg/ml WB 0.3 - 1 µg/ml Application Note WB: Recommend incubate at RT for 1h. IHC-P: Antigen Retrieval: Steam tissue section in Citrate buffer (pH 6.0). * The dilutions indicate recommended starting dilutions and the optimal dilutions or concentrations should be determined by the scientist. Calculated Mw 97 kDa Properties Form Liquid Purification Purified from goat serum by ammonium sulphate precipitation followed by antigen affinity chromatography using the immunizing peptide. Buffer Tris saline (pH 7.3), 0.02% Sodium azide and 0.5% BSA Preservative 0.02% Sodium azide Stabilizer 0.5% BSA www.arigobio.com 1/3 Concentration 0.5 mg/ml Storage instruction For continuous use, store undiluted antibody at 2-8°C for up to a week. For long-term storage, aliquot and store at -20°C or below. Storage in frost free freezers is not recommended. Avoid repeated freeze/thaw cycles. -

Aneuploidy: Using Genetic Instability to Preserve a Haploid Genome?

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science (Cancer Biology) Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Submitted by: Ramona Ramdath In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science Examination Committee Signature/Date Major Advisor: David Allison, M.D., Ph.D. Academic James Trempe, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: David Giovanucci, Ph.D. Randall Ruch, Ph.D. Ronald Mellgren, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: April 10, 2009 Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Ramona Ramdath University of Toledo, Health Science Campus 2009 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandfather who died of lung cancer two years ago, but who always instilled in us the value and importance of education. And to my mom and sister, both of whom have been pillars of support and stimulating conversations. To my sister, Rehanna, especially- I hope this inspires you to achieve all that you want to in life, academically and otherwise. ii Acknowledgements As we go through these academic journeys, there are so many along the way that make an impact not only on our work, but on our lives as well, and I would like to say a heartfelt thank you to all of those people: My Committee members- Dr. James Trempe, Dr. David Giovanucchi, Dr. Ronald Mellgren and Dr. Randall Ruch for their guidance, suggestions, support and confidence in me. My major advisor- Dr. David Allison, for his constructive criticism and positive reinforcement.