This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Sasl) in a Bilingual-Bicultural Approach in Education of the Deaf

APPLICATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGE (SASL) IN A BILINGUAL-BICULTURAL APPROACH IN EDUCATION OF THE DEAF Philemon Abiud Okinyi Akach August 2010 APPLICATION OF SOUTH AFRICAN SIGN LANGUAGE (SASL) IN A BILINGUAL-BICULTURAL APPROACH IN EDUCATION OF THE DEAF By Philemon Abiud Omondi Akach Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the degree PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES (DEPARTMENT OF AFROASIATIC STUDIES, SIGN LANGUAGE AND LANGUAGE PRACTICE) at the UNIVERSITY OF FREE STATE Promoter: Dr. Annalie Lotriet. Co-promoter: Dr. Debra Aarons. August 2010 Declaration I declare that this thesis, which is submitted to the University of Free State for the degree Philosophiae Doctor, is my own independent work and has not previously been submitted by me to another university or faculty. I hereby cede the copyright of the thesis to the University of Free State Philemon A.O. Akach. Date. To the deaf children of the continent of Africa; may you grow up using the mother tongue you don’t acquire from your mother? Acknowledgements I would like to say thank you to the University of the Free State for opening its doors to a doubly marginalized language; South African Sign Language to develop and grow not only an academic subject but as the fastest growing language learning area. Many thanks to my supervisors Dr. A. Lotriet and Dr. D. Aarons for guiding me throughout this study. My colleagues in the department of Afroasiatic Studies, Sign Language and Language Practice for their support. Thanks to my wife Wilkister Aluoch and children Sophie, Susan, Sylvia and Samuel for affording me space to be able to spend time on this study. -

A Human-Editable Sign Language Representation for Software Editing—And a Writing System?

A human-editable Sign Language representation for software editing—and a writing system? Michael Filhol [email protected] LIMSI, CNRS, Université Paris Saclay Orsay, France Abstract To equip SL with software properly, we need an input system to rep- resent and manipulate signed contents in the same way that every day software allows to process written text. Refuting the claim that video is good enough a medium to serve the purpose, we propose to build a repres- entation that is: editable, queryable, synthesisable and user-friendly—we define those terms upfront. The issue being functionally and conceptually linked to that of writing, we study existing writing systems, namely those in use for vocal languages, those designed and proposed for SLs, and more spontaneous ways in which SL users put their language in writing. Ob- serving each paradigm in turn, we move on to propose a new approach to satisfy our goals of integration in software. We finally open the prospect of our proposition being used outside of this restricted scope, as a writing system in itself, and compare its properties to the other writing systems presented. 1 Motivation and goals The main motivation here is to equip Sign Language (SL) with software and foster implementation as available tools for SL are paradoxically limited in such digital times. For example, translation assisting software would help respond arXiv:1811.01786v1 [cs.CL] 5 Nov 2018 to the high demand for accessible content and information. But equivalent text-to-text software relies on source and target written forms to work, whereas similar SL support seems impossible without major revision of the typical user interface. -

AN ETHNOGRAPHY of DEAF PEOPLE in TANZANIA By

THEY HAVE TO SEE US: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF DEAF PEOPLE IN TANZANIA by Jessica C. Lee B.A., University of Northern Colorado, 2001 M.A., Gallaudet University, 2004 M.A., University of Colorado, 2006 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the degree requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology 2012 ii This thesis entitled: They Have To See Us: an Ethnography of Deaf People in Tanzania written by Jessica Chantelle Lee has been approved for the Department of Anthropology J. Terrence McCabe Dennis McGilvray Paul Shankman --------------------------------------------- Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. IRB protocol # 13090619 iii ABSTRACT They Have To See Us: an Ethnography of Deaf People in Tanzania Jessica Lee Department of Anthropology Thesis directed by Professor J. Terrence McCabe This dissertation explores the relationship between Tanzanian deaf people and mainstream society, as well as dynamics within deaf communities. I argue that deaf people who do participate in NGOs and other organizations that provide support to deaf people, do so strategically. In order to access services and improve their own lives and the lives of their families, deaf people in Tanzania move comfortably and fluidly between identity groups that are labeled as disabled or only as deaf. Through intentional use of the interventions provided by various organizations, deaf people are able to carve out deaf spaces that act as places for transmission of information, safe areas to learn and use sign language, and sites of network and community development among other deaf people. -

21. Bibliografía

BIBLIOGRAFÍA1121 A) Material impreso y/o digitalizado Abergel, R. (s. d.): L’enfant sourd et la psychomôtricite. Hommage à Pereire. Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du Certificat de capacité d‘orthophoniste (Memoria no publicada pre- sentada para la obtención del certificado de capacidad de ortofonista. Universidad Louis Pasteur. Facultad de Medicina. Strasbourg). Acquier, Marie-Laure (2000): «Los Tratados en prosa de Antonio López de Vega: aproxima- ción al discurso político en el siglo XVII», Cuadernos de Historia Moderna, n.º 24, 11-31, pp. 85-106. Aftonio, Elio Festo (1961): De metris, en H. Keil (ed.): Grammatici Latini, vol. VI, Hildes- heim, Olms; reimpr de la. 1.ª ed. de Leipzig, 1874, pp. 31-173. Aguado Díaz, A. L. (1995): Historia de las Deficiencias, Madrid, Escuela Libre Editorial (Col. Tesis y Praxis). Aguirre Lora, G. M. E. (dir./1993): Juan Amós Comenio: obra, andanzas, atmosferas en el IV centenario de su nacimiento. (1592-1992), Coyoacán, Centro de Estudios sobre la Universidad. Agulló y Cobo, Mercedes (1992): La imprenta y el comercio de libros en Madrid (siglos XVI- XVIII), Madrid, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Ainscow, M. (2001): Desarrollo de escuelas inclusivas. Ideas propuestas y experiencias para mejorar las instituciones escolares, Madrid, Narcea. Alcuino de York (1851): Grammatica, en Frobenius (ed.): Opera omnia, en J.-P. Migne: Patro- logia Latina, vol. CI, Turnholti, Brepols, reimpr.de la 1.ª ed. de París, 1777, cols. 849-902. Aldea Vaquero, Quintín de (1986): España y Europa en el siglo XVII. Correspondencia de Saavedra Faxardo. 1631-1633, Madrid, CSIC. Alemán, Mateo (1609): Ortografía castellana, México, Jerónimo Balli. -

The Two Hundred Years' War in Deaf Education

THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS' WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy By A. Tellings PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/146075 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2020-04-15 and may be subject to change. THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS* WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy By A. Tellings THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS' WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy EEN WETENSCHAPPELIJKE PROEVE OP HET GEBIED VAN DE SOCIALE WETENSCHAPPEN PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR AAN DE KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT NIJMEGEN, VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VAN DECANEN IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP 5 DECEMBER 1995 DES NAMIDDAGS TE 3.30 UUR PRECIES DOOR AGNES ELIZABETH JACOBA MARIA TELLINGS GEBOREN OP 9 APRIL 1954 TE ROOSENDAAL Dit onderzoek werd verricht met behulp van subsidie van de voormalige Stichting Pedon, NWO Mediagroep Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen PROMOTOR: Prof.Dr. A.W. van Haaften COPROMOTOR: Dr. G.L.M. Snik 1 PREFACE The methods controversy in deaf education has fascinated me since I visited the International Congress on Education of the Deaf in Hamburg (Germany) in 1980. There I was struck by the intemperate emotions by which the methods controversy is attended. This book is an attempt to understand what this controversy really is about I would like to thank first and foremost Prof.Wouter van Haaften and Dr. -

14 a Two-Handed Manual Alphabet in the United States

14 A Two-Handed Manual Alphabet in the United States Ruth C.Locw EducatirJnal 1·esting S'ervice Princeton, NJ C. Ta11eAkamatst1 Toronto District School Board Ontario , Canada Mary Lanaville CS'CInterpreters, Inc. 1-ludson, 1VC Our contribution to this fcstscl1rift has its origins in the grassroots of the Deaf community as vvel] a.sin the hallowed halls of tl1e ivory tower. The 1)io11eering work of Edvvard Klima and Ursula Bel lugi, from data collection to technical argumentation to acqt tiring funding for sign language research , has allowed a great number of scholars to be11efit either directly or indirectl y. Sttch be11efit has also accrt ted to n1embers of the Deaf· commltnity, who have always known that tl1ere existed a language and culture , but who are now empo,;vered to study it from tl1e inside . This piece, writte11 by a linguist , a psychologist, and an interpreter married to a Deaf man , demonstrates the influence that Klima and Be llugi have had on 1nany levels of scholarship and 011the lives of Deaf people. Dur ing a course on American Sign L anguagc (ASL) structure , a sign meaning "no good " came to our attention . It vva.s pe1formed using vvl1at appeared to be the British t,vo-ha.nded alphabet letters N-G. This sign ,,vas describ ed by Battison (1978) , but according to our informant , it was n.ot Britis h. It was "from the old alphabet - tl1e o.ne all the older De af people know." This "old alphabet " is a two-handed An1erica11 ma11ttal alphabe t. The most common form of· American fingerspelling is single -ha.nded. -

Expanding Information Access Through Data-Driven Design

©Copyright 2018 Danielle Bragg Expanding Information Access through Data-Driven Design Danielle Bragg A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2018 Reading Committee: Richard Ladner, Chair Alan Borning Katharina Reinecke Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Computer Science & Engineering University of Washington Abstract Expanding Information Access through Data-Driven Design Danielle Bragg Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Richard Ladner Computer Science & Engineering Computer scientists have made progress on many problems in information access: curating large datasets, developing machine learning and computer vision, building extensive networks, and designing powerful interfaces and graphics. However, we sometimes fail to fully leverage these modern techniques, especially when building systems inclusive of people with disabilities (who total a billion worldwide [168], and nearly one in five in the U.S. [26]). For example, visual graphics and small text may exclude people with visual impairments, and text-based resources like search engines and text editors may not fully support people using unwritten sign languages. In this dissertation, I argue that if we are willing to break with traditional modes of information access, we can leverage modern computing and design techniques from computer graphics, crowdsourcing, topic modeling, and participatory design to greatly improve and enrich access. This dissertation demonstrates this potential -

Advances in the Science and Application of Animal Training International Society for Anthrozoology (ISAZ)

International Society for Anthrozoology (ISAZ) 13th Annual Conference Advances in the Science and Application of Animal Training 6th October 2004 Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre, Glasgow, UK Satellite meeting to IAHAIO 2004 Picture in here In conjunction with the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare Science in the Service of Animal Welfare WELCOME TO GLASGOW Training has long been recognised as an important component in the successful adaptation of companion animals, their inclusion in sporting events and other recreational activities. An extensive folk literature exists relating to the training of these animals. Knowledge and practice based upon scientific principles, such as classical conditioning and instrumental learning may also be employed. Less recognised is the contribution relevant training can have on the management and husbandry of other animals eg. on farms, in zoos and the laboratory. This meeting aims to discuss recent developments in learning theory and related fields, in the methodologies and techniques of training. It will also consider the application of these for practical training of animals. It seeks to bring together veterinarians, animal scientists, ethologists, psychologists, animal trainers and others who work with animals to share knowledge and good practice. It hopes to encourage a wider consideration of the ways training can be used to improve the husbandry, management and welfare of animals. ISAZ 2004 is a satellite meeting to the 2004 world conference of the International Association of Human-Animal Interaction Organisations and we are grateful to IAHAIO for their support of the meeting. We are also grateful for the kind support of the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare in the organisation of the meeting and their help in compiling the programme and preparation of the abstract booklets. -

Deaf History Notes Unit 1.Pdf

Deaf History Notes by Brian Cerney, Ph.D. 2 Deaf History Notes Table of Contents 5 Preface 6 UNIT ONE - The Origins of American Sign Language 8 Section 1: Communication & Language 8 Communication 9 The Four Components of Communication 11 Modes of Expressing and Perceiving Communication 13 Language Versus Communication 14 The Three Language Channels 14 Multiple Language Encoding Systems 15 Identifying Communication as Language – The Case for ASL 16 ASL is Not a Universal Language 18 Section 2: Deaf Education & Language Stability 18 Pedro Ponce DeLeón and Private Education for Deaf Children 19 Abbé de l'Epée and Public Education for Deaf Children 20 Abbé Sicard and Jean Massieu 21 Laurent Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet 23 Martha's Vineyard 24 The Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons 27 Unit One Summary & Review Questions 30 Unit One Bibliography & Suggested Readings 32 UNIT TWO - Manualism & the Fight for Self-Empowerment 34 Section 1: Language, Culture & Oppression 34 Language and Culture 35 The Power of Labels 35 Internalized Oppression 37 Section 2: Manualism Versus Oralism 37 The New England Gallaudet Association 37 The American Annals of the Deaf 38 Edward Miner Gallaudet, the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, and the National Deaf-Mute College 39 Alexander Graham Bell and the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf 40 The National Association of the Deaf 42 The International Convention of Instructors of the Deaf in Milan, Italy 44 -

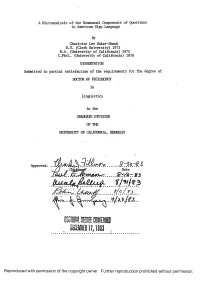

Iffls G E M M E U . IW EB17J8S3

A M icroanalysis o f the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language By Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk B.S. (Clark U niversity) 1972 M.A. O Jniversity o f C alifornia) 1975 C.Phil. (University of California) 1978 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Approved: Date IfflSGEMMEU . IWEB17J8S3 \ Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A Microanalysis of the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language C opyright © 1983 by Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements .................................................................................. v ii List of Figures .................................................................................... x List of Photographs ..................................... x ii List of Drawings .......................................................................................x i i i Transcription Conventions .................................................... iv C hapter I - EXPERIENCES OF DEAF PEOPLE IN A HEARING WORLD ................................................. 1 1.0 Formal education of deaf people: historical review •• 1 1.1 -

The Development of Education for Deaf People

1 Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people The development of education for deaf people Legacy of the Past The book Legacy of the Past (Some aspects of the history of blind educa- tion, deaf education, and deaf-blind education with emphasis on the time before 1900) contains three chapters: Chapter 1: The development of education for blind people Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people Chapter 3: The development of education for deaf-blind people In all 399 pp. An internet edition of the whole book in one single document would be very unhandy. Therefore, I have divided the book into three documents (three inter- netbooks). In all, the three documents contain the whole book. Legacy of the Past. This Internetbook is Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people. Foreword In his Introduction the author expresses very clearly that this book is not The history of blind education, deaf education and deaf-blind education but some aspects of their history of education with emphasis on the time before 1900. Nevertheless - having had the privilege of reading it - my opinion is that this volume must be one of the most extensive on the market today regarding this part of the history of special education. For several years now I have had the great pleasure of working with the author, and I am not surprised by the fact that he really has gone to the basic sources trying to find the right answers and perspectives. Who are they - and in what ways have societies during the centuries faced the problems? By going back to ancient sources like the Bible, the Holy Koran and to Nordic Myths the author gives the reader an exciting perspective; expressed, among other things, by a discussion of terms used through our history. -

Analysis of Notation Systems for Machine Translation of Sign Languages

Analysis of Notation Systems for Machine Translation of Sign Languages Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Science (Honours) of Rhodes University Jessica Jeanne Hutchinson Grahamstown, South Africa November 2012 Abstract Machine translation of sign languages is complicated by the fact that there are few stan- dards for sign languages, both in terms of the actual languages used by signers within regions and dialogue groups, and also in terms of the notations with which sign languages are represented in written form. A standard textual representation of sign languages would aid in optimising the translation process. This area of research still needs to determine the best, most efficient and scalable tech- niques for translation of sign languages. Being a young field of research, there is still great scope for introducing new techniques, or greatly improving on previous techniques, which makes comparing and evaluating the techniques difficult to do. The methods used are factors which contribute to the process of translation and need to be considered in an evaluation of optimising translation systems. This project analyses sign language notation systems; what systems exists, what data is currently available, and which of them might be best suited for machine translation purposes. The question being asked is how using a textual representation of signs could aid machine translation, and which notation would best suit the task. A small corpus of SignWriting data was built and this notation was shown to be the most accessible. The data was cleaned and run through a statistical machine translation system. The results had limitations, but overall are comparable to other translation systems, showing that translation using a notation is possible, but can be greatly improved upon.