(Sasl) in a Bilingual-Bicultural Approach in Education of the Deaf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Ugandan Sign Language

Communicating with your deaf child in... Ugandan Sign Language Book One 1 Contents 3 Contents 5 Introduction 6 Chapters 47 Notes 2 6 Chapter 1 Greetings and Courtesy 10 Chapter 2 Friends and Family 13 Chapter 3 Fingerspelling and Numbers 16 Chapter 4 Going Shopping 24 Chapter 5 The World and Far Away 31 Chapter 6 Children’s Rights 36 Chapter 7 Health 42 Chapter 8 Express Yourself 3 4 Introduction This book is for parents, carers, guardians and families with a basic knowledge of Ugandan Sign Language (USL) who want to develop their USL skills to communicate at a more advanced level with their deaf children using simple phrases and sentences. This is the second edition of the book, first published in 2013 now with added amends and content following consultation with users. We want this book to: • Empower families to improve their communication skills • Ensure deaf children are included in their family life and in their communities • Empower deaf children to express their own views and values and develop the social skills they need to lead independent lives • Allow deaf children to fulfil their potential How to use this book Sign language is a visual language using gesture, body movements and facial expressions to communicate. This book has illustrated pictures to show you how to sign different words. The arrows show you the hand movements needed to make the sign correctly. This book is made up of eight chapters, each covering different topic areas. Each chapter has a section on useful vocabulary followed by activities to enable you to practise phrases using the words learned in the chapter. -

Iconicity As a Pervasive Force in Language: Evidence from Ghanaian Sign

Iconicity as a pervasive force in language: Evidence from Ghanaian Sign Language and Adamorobe Sign Language By Mary Edward A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Brighton for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities University of Brighton 2021 Abstract In this dissertation, I investigate various manifestations of iconicity and how these are demonstrated in the visual-spatial modality, focusing specifically on Ghanaian Sign Language (GSL) and Adamorobe Sign Language (AdaSL). The dissertation conducts three main empirical analyses comparing GSL and AdaSL. The data for the analyses were elicited from deaf participants using lexical elicitation and narrative tasks. The first study considers iconicity in GSL and AdaSL lexical items. This study additionally compares the iconic strategies used by signers to those produced in gestures by hearing non-signers in the surrounding communities. The second study investigates iconicity in the spatial domain, focusing on the iconic use of space to depict location, motion, action. The third study looks specifically at the use of, simultaneous constructions, and compares the use of different types of simultaneous constructions between the two sign languages. Finally, the dissertation offers a theoretical analysis of the data across the studies from a cognitive linguistics perspective on iconicity in language. The study on lexical iconicity compares GSL and AdaSL signers’ use of iconic strategies across five semantic categories: Handheld tools, Clothing & Accessories, Furniture & Household items, Appliances, and Nature. Findings are discussed with respect to patterns of iconicity across semantic categories, and with respect to similarities and differences between signs and gestures. -

21. Bibliografía

BIBLIOGRAFÍA1121 A) Material impreso y/o digitalizado Abergel, R. (s. d.): L’enfant sourd et la psychomôtricite. Hommage à Pereire. Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du Certificat de capacité d‘orthophoniste (Memoria no publicada pre- sentada para la obtención del certificado de capacidad de ortofonista. Universidad Louis Pasteur. Facultad de Medicina. Strasbourg). Acquier, Marie-Laure (2000): «Los Tratados en prosa de Antonio López de Vega: aproxima- ción al discurso político en el siglo XVII», Cuadernos de Historia Moderna, n.º 24, 11-31, pp. 85-106. Aftonio, Elio Festo (1961): De metris, en H. Keil (ed.): Grammatici Latini, vol. VI, Hildes- heim, Olms; reimpr de la. 1.ª ed. de Leipzig, 1874, pp. 31-173. Aguado Díaz, A. L. (1995): Historia de las Deficiencias, Madrid, Escuela Libre Editorial (Col. Tesis y Praxis). Aguirre Lora, G. M. E. (dir./1993): Juan Amós Comenio: obra, andanzas, atmosferas en el IV centenario de su nacimiento. (1592-1992), Coyoacán, Centro de Estudios sobre la Universidad. Agulló y Cobo, Mercedes (1992): La imprenta y el comercio de libros en Madrid (siglos XVI- XVIII), Madrid, Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Ainscow, M. (2001): Desarrollo de escuelas inclusivas. Ideas propuestas y experiencias para mejorar las instituciones escolares, Madrid, Narcea. Alcuino de York (1851): Grammatica, en Frobenius (ed.): Opera omnia, en J.-P. Migne: Patro- logia Latina, vol. CI, Turnholti, Brepols, reimpr.de la 1.ª ed. de París, 1777, cols. 849-902. Aldea Vaquero, Quintín de (1986): España y Europa en el siglo XVII. Correspondencia de Saavedra Faxardo. 1631-1633, Madrid, CSIC. Alemán, Mateo (1609): Ortografía castellana, México, Jerónimo Balli. -

A Lexical Comparison of South African Sign Language and Potential Lexifier Languages

A lexical comparison of South African Sign Language and potential lexifier languages by Andries van Niekerk Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Masters in General Linguistics at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisors: Dr Kate Huddlestone & Prof Anne Baker Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Department of General Linguistics March, 2020 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Andries van Niekerk March 2020 Copyright © 2020 University of Stellenbosch All rights reserved 1 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT South Africa’s history of segregation was a large contributing factor for lexical variation in South African Sign Language (SASL) to come about. Foreign sign languages certainly had a presence in the history of deaf education; however, the degree of influence foreign sign languages has on SASL today is what this study has aimed to determine. There have been very limited studies on the presence of loan signs in SASL and none have included extensive variation. This study investigates signs from 20 different schools for the deaf and compares them with signs from six other sign languages and the Paget Gorman Sign System (PGSS). A list of lemmas was created that included the commonly used list of lemmas from Woodward (2003). -

The Two Hundred Years' War in Deaf Education

THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS' WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy By A. Tellings PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/146075 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2020-04-15 and may be subject to change. THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS* WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy By A. Tellings THE TWO HUNDRED YEARS' WAR IN DEAF EDUCATION A reconstruction of the methods controversy EEN WETENSCHAPPELIJKE PROEVE OP HET GEBIED VAN DE SOCIALE WETENSCHAPPEN PROEFSCHRIFT TER VERKRIJGING VAN DE GRAAD VAN DOCTOR AAN DE KATHOLIEKE UNIVERSITEIT NIJMEGEN, VOLGENS BESLUIT VAN HET COLLEGE VAN DECANEN IN HET OPENBAAR TE VERDEDIGEN OP 5 DECEMBER 1995 DES NAMIDDAGS TE 3.30 UUR PRECIES DOOR AGNES ELIZABETH JACOBA MARIA TELLINGS GEBOREN OP 9 APRIL 1954 TE ROOSENDAAL Dit onderzoek werd verricht met behulp van subsidie van de voormalige Stichting Pedon, NWO Mediagroep Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen PROMOTOR: Prof.Dr. A.W. van Haaften COPROMOTOR: Dr. G.L.M. Snik 1 PREFACE The methods controversy in deaf education has fascinated me since I visited the International Congress on Education of the Deaf in Hamburg (Germany) in 1980. There I was struck by the intemperate emotions by which the methods controversy is attended. This book is an attempt to understand what this controversy really is about I would like to thank first and foremost Prof.Wouter van Haaften and Dr. -

Typology of Signed Languages: Differentiation Through Kinship Terminology Erin Wilkinson

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of New Mexico University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Linguistics ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 7-1-2009 Typology of Signed Languages: Differentiation through Kinship Terminology Erin Wilkinson Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds Recommended Citation Wilkinson, Erin. "Typology of Signed Languages: Differentiation through Kinship Terminology." (2009). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds/40 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TYPOLOGY OF SIGNED LANGUAGES: DIFFERENTIATION THROUGH KINSHIP TERMINOLOGY BY ERIN LAINE WILKINSON B.A., Language Studies, Wellesley College, 1999 M.A., Linguistics, Gallaudet University, 2001 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Linguistics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico August, 2009 ©2009, Erin Laine Wilkinson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii DEDICATION To my mother iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Many thanks to Barbara Pennacchi for kick starting me on my dissertation by giving me a room at her house, cooking me dinner, and making Italian coffee in Rome during November 2007. Your endless support, patience, and thoughtful discussions are gratefully taken into my heart, and I truly appreciate what you have done for me. I heartily acknowledge Dr. William Croft, my advisor, for continuing to encourage me through the long number of months writing and rewriting these chapters. -

The Deaf of South Sudan the South Sudanese Sign Language Community South Sudan Achieved Its Independence in 2011 from the Republic of Sudan to Its North

Profile Year: 2015 People and Language Detail Report Language Name: South Sudan Sign Language ISO Language Code: not yet The Deaf of South Sudan The South Sudanese Sign Language Community South Sudan achieved its independence in 2011 from the Republic of Sudan to its north. Prior to that, Sudan suffered under two civil wars. The second, which began in 1976, pitted the Sudanese government against the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and lasted for over twenty years. These wars have led to significant suffering among the Sudanese and South Sudanese people, including major gaps in infrastructure development and significant displacement of various people groups. All of this war has traumatized the people of Sudan, and the Deaf in particular. The country appears to have a very small middle class, while a vast majority of its citizens are either very wealthy or extremely poor. The Deaf in South Sudan tend to be the poorest of the poor. Some cannot afford food and must stay at home with families (even though the home environ- ment often means that no one can communicate with them). There are currently no Deaf schools in South Sudan. Deaf schools are photo by DOOR International typically the center of language and cultural development for the Deaf of a country. A lack of Deaf schools means that there is a need for a central cultural organization among the Deaf. Deaf churches could function in this Primary Religion: role if they were well-established. There is currently only one Deaf church in Non-religious __________________________________________________ South Sudan. This church meets in Juba, and has fewer than 50 members. -

Deaf History Notes Unit 1.Pdf

Deaf History Notes by Brian Cerney, Ph.D. 2 Deaf History Notes Table of Contents 5 Preface 6 UNIT ONE - The Origins of American Sign Language 8 Section 1: Communication & Language 8 Communication 9 The Four Components of Communication 11 Modes of Expressing and Perceiving Communication 13 Language Versus Communication 14 The Three Language Channels 14 Multiple Language Encoding Systems 15 Identifying Communication as Language – The Case for ASL 16 ASL is Not a Universal Language 18 Section 2: Deaf Education & Language Stability 18 Pedro Ponce DeLeón and Private Education for Deaf Children 19 Abbé de l'Epée and Public Education for Deaf Children 20 Abbé Sicard and Jean Massieu 21 Laurent Clerc and Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet 23 Martha's Vineyard 24 The Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons 27 Unit One Summary & Review Questions 30 Unit One Bibliography & Suggested Readings 32 UNIT TWO - Manualism & the Fight for Self-Empowerment 34 Section 1: Language, Culture & Oppression 34 Language and Culture 35 The Power of Labels 35 Internalized Oppression 37 Section 2: Manualism Versus Oralism 37 The New England Gallaudet Association 37 The American Annals of the Deaf 38 Edward Miner Gallaudet, the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb, and the National Deaf-Mute College 39 Alexander Graham Bell and the American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf 40 The National Association of the Deaf 42 The International Convention of Instructors of the Deaf in Milan, Italy 44 -

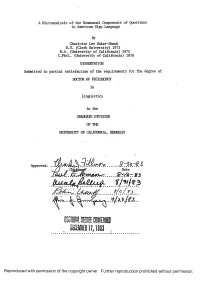

Iffls G E M M E U . IW EB17J8S3

A M icroanalysis o f the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language By Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk B.S. (Clark U niversity) 1972 M.A. O Jniversity o f C alifornia) 1975 C.Phil. (University of California) 1978 DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Approved: Date IfflSGEMMEU . IWEB17J8S3 \ Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. A Microanalysis of the Nonmanual Components of Questions in American Sign Language C opyright © 1983 by Charlotte Lee Baker-Shenk Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ....................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements .................................................................................. v ii List of Figures .................................................................................... x List of Photographs ..................................... x ii List of Drawings .......................................................................................x i i i Transcription Conventions .................................................... iv C hapter I - EXPERIENCES OF DEAF PEOPLE IN A HEARING WORLD ................................................. 1 1.0 Formal education of deaf people: historical review •• 1 1.1 -

The Development of Education for Deaf People

1 Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people The development of education for deaf people Legacy of the Past The book Legacy of the Past (Some aspects of the history of blind educa- tion, deaf education, and deaf-blind education with emphasis on the time before 1900) contains three chapters: Chapter 1: The development of education for blind people Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people Chapter 3: The development of education for deaf-blind people In all 399 pp. An internet edition of the whole book in one single document would be very unhandy. Therefore, I have divided the book into three documents (three inter- netbooks). In all, the three documents contain the whole book. Legacy of the Past. This Internetbook is Chapter 2: The development of education for deaf people. Foreword In his Introduction the author expresses very clearly that this book is not The history of blind education, deaf education and deaf-blind education but some aspects of their history of education with emphasis on the time before 1900. Nevertheless - having had the privilege of reading it - my opinion is that this volume must be one of the most extensive on the market today regarding this part of the history of special education. For several years now I have had the great pleasure of working with the author, and I am not surprised by the fact that he really has gone to the basic sources trying to find the right answers and perspectives. Who are they - and in what ways have societies during the centuries faced the problems? By going back to ancient sources like the Bible, the Holy Koran and to Nordic Myths the author gives the reader an exciting perspective; expressed, among other things, by a discussion of terms used through our history. -

Meaning of Deaf Empowerment

Meaning of Deaf Empowerment Exploring Development and Deafness in Namibia Iðunn Ása Óladóttir Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í þróunarfræðum Félagsvísindasvið Meaning of Deaf Empowerment Exploring Development and Deafness in Namibia Iðunn Ása Óladóttir Lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í þróunarfræðum Leiðbeinendur: Davíð Bjarnason og Jónína Einarsdóttir Félags- og mannvísindadeild Félagsvísindasvið Háskóla Íslands Júní 2014 Ritgerð þessi er lokaverkefni til MA–gráðu í þróunarfræðum og er óheimilt að afrita ritgerðina á nokkurn hátt nema með leyfi rétthafa. © Iðunn Ása Óladóttir 2014 Reykjavík, Ísland 2014 Abstract Empowerment is a recent and a popular concept within international development studies which emphasizes people-centered approaches where the beneficiaries in developing countries are seen as active participants rather than merely being passive recipients of aid. The aim of this research is to explore the influence of development programs on empowerment of Deaf individuals based a fieldwork that took place in Namibia from September to October 2012 through the Centre for Communication and Deaf Studies (CCDS) in Windhoek. The focus was in part on a development project of the Icelandic International Development Agency (ICEIDA) which was carried out in 2006-2010 in Namibia. The research followed participation observation with qualitative methodology based on interviews, conversations and interaction with the group of participants. The results suggest that despite some great improvements in field of deafness in Namibia, the fact remains that Deaf in Namibia are still excluded from education to a large extent. The educational system does not fully recognize the needs of Deaf pupils and the access to interpreters remains a barrier. It was concluded that despite the willingness among specialists in Namibia there is still a lack within the strict system of Namibia to allow for exceptions when it comes to put things in action.