Intimate Partner Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Have You Ever? Oh, When?

Activate: Games for Learning American English Game 9: Have You Ever…? Oh, When? Have You Ever…? Oh, When? gives students practice with common conversational moves by asking and telling about past experiences. The teacher may want to explain the use of the present perfect and the meaning of “ever” in “have you ever.” Instructions 1. Have students (the players) sit in groups of 3–4. 2. Determine who goes first and progress clockwise or counter-clockwise. 3. Each player rolls the dice in turn. 4. On their turns, the players move their game pieces along the path according to the number of spaces indicated by the dice. 5. On the space where they land, the players read the question aloud. 6. The players respond to their question. If the answer is “yes,” players should say the last time they did the activity. If the answer is “no,” players should tell something that they have done that is related. 7. The game continues until one or all players reach the ‘Finish’ space. “Player Talk” in Have You Ever…? Oh, When? Cue “Player Talk” Have you ever No I haven’t, but I have swum in an ocean. (Simple swum in a river? response) Have you ever Yes, I have. The last time was when I visited my aunt. I watched a baseball saw a game on TV. (Complex response) game? 27 Activate: Games for Learning American English Game Squares START: WE’RE SO READY! 1. Have you ever swum in a river? 2. Have you ever watched a baseball game? 3. -

Welsh Physics Teachers Conference Brecon 2021 a Blended Approach #Breconconf2021

Welsh Physics Teachers Conference Brecon 2021 A Blended Approach #BreconConf2021 Friday 8th to Friday 15th October 2021 For all teachers of Physics… join the Welsh Physics Teachers Conference Brecon 2021, this year between 8th – 15th October 2021. A fabulous free week of presentations and workshops for teachers, technicians and PGCE students with opportunities to network with colleagues. We will offer workshops shows and presentations between 1.30pm and 3pm each afternoon and 4pm until 8pm each evening Monday – Friday, as well as a quiz, a trek and workshops at an Alpaca Farm in the Brecon Beacons on Saturday morning (10:30am – 3.30pm), an opportunity to discuss the relationship between Physics and faith, networking opportunities with colleagues from Ireland and New Zealand – and a virtual tour of Penderyn Whisky Distillery in the heart of the Brecon Beacons. Please join us for a full week of workshops and inspiring lectures, which include: ‘Materials in Action’ (Dr Diane Aston, IOM3); ‘The Digital Century’ (Professor Neil Stansfield, National Physical Laboratory); ‘From cat skin to submarines – soft materials that are a bit of a stretch’ (Professor Helen F Gleeson, Leeds University) and ‘From Deep Space to Deep Impact: bringing the solar system down to Earth’ (Professor Paul Roche, Cardiff University). Workshops will include: ‘Keeping up the Momentum’; ’Physics, weather and forecasting’; ‘Tones, Tines and Tings’ and ‘What alpacas and other animals can teach us about Physics’. Technicians are welcome to attend all the events and we will also be hosting a technicians event: ‘The Physics Prep Room’ on Thursday 14th October. FREE registration via Eventbrite is at welshphysicsteachersconference2021.eventbrite.co.uk Please encourage colleagues from other schools and organisations to attend. -

Jazz Quartess Songlist Pop, Motown & Blues

JAZZ QUARTESS SONGLIST POP, MOTOWN & BLUES One Hundred Years A Thousand Years Overjoyed Ain't No Mountain High Enough Runaround Ain’t That Peculiar Same Old Song Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Sexual Healing B.B. King Medley Signed, Sealed, Delivered Boogie On Reggae Woman Soul Man Build Me Up Buttercup Stop In The Name Of Love Chasing Cars Stormy Monday Clocks Summer In The City Could It Be I’m Fallin’ In Love? Superstition Cruisin’ Sweet Home Chicago Dancing In The Streets Tears Of A Clown Everlasting Love (This Will Be) Time After Time Get Ready Saturday in the Park Gimme One Reason Signed, Sealed, Delivered Green Onions The Scientist Groovin' Up On The Roof Heard It Through The Grapevine Under The Boardwalk Hey, Bartender The Way You Do The Things You Do Hold On, I'm Coming Viva La Vida How Sweet It Is Waste Hungry Like the Wolf What's Going On? Count on Me When Love Comes To Town Dancing in the Moonlight Workin’ My Way Back To You Every Breath You Take You’re All I Need . Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic You’ve Got a Friend Everything Fire and Rain CONTEMPORARY BALLADS Get Lucky A Simple Song Hey, Soul Sister After All How Sweet It Is All I Do Human Nature All My Life I Believe All In Love Is Fair I Can’t Help It All The Man I Need I Can't Help Myself Always & Forever I Feel Good Amazed I Was Made To Love Her And I Love Her I Saw Her Standing There Baby, Come To Me I Wish Back To One If I Ain’t Got You Beautiful In My Eyes If You Really Love Me Beauty And The Beast I’ll Be Around Because You Love Me I’ll Take You There Betcha By Golly -

ND to Increase Minority

Chilling out ACCENT: Sarcastic Slap Colder Tuesday with a40 per cent chance of snow showers 0 ^ High 25 to 30. Very cold at night with a 40 percent chance VIEWPOINT: SMC Election Endorsement of snow showers. VOL. XXI, NO. 96 TUESDAY, FEBRUARY 23, 1988 the independent newspaper serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's ND to increase minority aid By CHRIS BEDNARSKI tee said would enhance all News Editor aspects of minority undergrad uate and graduate life at Notre Notre Dame will seek signif Dame. icant increases in minority en The Univeristy will also in rollment in the next four years crease the number of minority through formation of a $12 mil faculty members, O’Meara lion endowment fund forsaid. Fourteen new faculty pos minority financial aid, Univeritions will be targeted sity President Father Edward primarily for blacks, Hispanics Malloy announced Monday. and American Indians. The money, which Provost In certain disciplines such as Timothy O’Meara said is engineering and science, already available, will help the however, where there are few University increase the num minority professors, he said ber of minority freshman from women may be hired to in the present 11 percent to 15 per crease their presence on the cent by 1992. Minority graduate faculty. “The primary enrollment, presently five per objective, however, is with cent, will double, he said. minorities,” he said. “ I have great confidence in The University will also the steps to be taken,” Malloy create academic support sys said at the afternoon press contems for minorities to help stu ference. -

APPLICATION for UNITED STATES MARSHAL Date

APPLICATION FOR UNITED STATES MARSHAL Date: _________________________ 1. Name: __________________________________________________________________ (List any other names you have used and the dates.) 2. Specific Judicial District Sought: Southern District Central District Northern District Eastern District 3. Business/Government Title: _________________________________________________ Firm/Office: _____________________________________________________________ Address: ________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ City County State Zip Phone: (____) ______________________ Fax: (____) __________________________ E-Mail: ___________________________ 4. Residence Address: _______________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ City County State Zip Phone: (____) ______________________ Fax: (____) __________________________ 5. Date of Birth: ______________________ Place of Birth: ________________________ 6. Ethnicity (Optional): ______________________ Gender: ___M ___F 7. Driver’s License No: ___________________ 1 8. Are you a registered voter? ___ Yes ___ No County: __________________________ List all current and past political party affiliations, with date: ______________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ 9. Identify your Member of Congress: ________________________________________________________________ -

Executive Director Applicants

Executive Director Applicants Requisition - 41000868-51254429-20120822091506 ( EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR-ELECTIONS COMMISSION ) Applicant - DIANE GUILLEMETTE Applicant Profile Including Qualifying Questions EEO & Veterans' Preference Information Layoff Status: No Claiming Veterans' Preference (A)?: Not Set Current Employee of Agency (A)?: No Florida Resident (A)?: No Previous Promotional Appointment (A)?: No Prescreening (Score: 88%) Desired Screen-In Screen- # Question Response Answer Question? out 1. This position is located in Yes Yes No No Tallahassee, Florida. Are you willing to work in Tallahassee? 2. The salary range for this position is Yes Yes No No $80,000.00 - $112,000.00. Are you willing to accept a salary in this range? 3. Do you have a Juris Doctor from a Yes Yes No No law school accredited by the American Bar Association? 4. Are you presently a member in Yes Yes No No good standing with the Florida Bar Association? 5. Have you ever been disciplined by No Yes No No the Florida Bar or another state bar? 6. If yes, please explain the offense N/A No No and any resulting disciplinary action? If no, please respond N/A. 7. How many years of professional 21 >= 5 No No experience in the practice of law (criminal and civil) do you have? 8. How many years of professional 8.5 No No experience in the practice of Florida administrative law do you have? 9. Please describe your Florida Counsel to multiple Florida boards. Rule No No administrative law experience. promulgation. Administrator for Agency for Persons with Disabilities DOAH hearings. DOAH litigation with all positions. 10. -

Wonderful! 100: a Centennial Celebration Published September 18Th, 2019 Listen on Themcelroy.Family

Wonderful! 100: A Centennial Celebration Published September 18th, 2019 Listen on TheMcElroy.family [theme music plays] Rachel: Hi, this is Rachel McElroy. Griffin: [laughs] Yeah. Okay, Mario. Yeah, I'll hit you up at the after party. Okay, man. Yeah, I'll see you there. Hey, this is Griffin McElroy. Rachel: And this is Wonderful! Griffin: Sorry, it‘s just… [sighs] I know we gotta focus on the show. I know it‘s our big day, but… we‘re on the red carpet, and like… Rachel: Yeah. Griffin: It‘s hard—if Mario Lopez comes up and wants to hang out at the after party, babe, it‘s like, I‘ve made it! Rachel: I know, but let‘s not celebrate our hundredth episode before we‘ve actually recorded it. Griffin: Right, this is the red carpet before the event. We‘re about to go to the first screening of our hundredth episode. For all I know, it could be a disaster. Mario may not want to talk to me after the party, so I need to check that—cash that check. Shit, if this is the energy I bring to ep one hundred, Mario‘s definitely not gonna wanna talk to me. Rachel: [laughs] Griffin: I just wanna tell him what a good job he did playing Greg Louganis in that one Lifetime movie. Rachel: Aw, jeez. Griffin: In that one commercial I saw for it where he asked if there was a blood nipple. Rachel: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. Griffin: You love that anecdote. Rachel: Yeah. Griffin: Who are you looking forward to seeing today on the big red way? Rachel: Well, Wallace Shawn. -

Legal Journal

————— August 27, 2021 ~ Vol.————— 108 • No. 35 ~ Media, PA NOTICES TO THE BAR LEGAL NOTICES Calendar: Change of Name 23 DCBA Events 3 Charter Application Nonprofit 24 PBI Seminars 4 Classified Ads 25 DCBA/CLE Seminars Estate and Trust Notices 14 “Condo and Homeowners Fictitious Name 25 Association Law” 5 Foreign Corporation 25 ——— Judgments 28 ADR Voluntary Settlement Program 9 Service by Publication 26 Early Deadline for Legal Journal 9 Sheriff ’s Sales 31 Elder Law Handbooks 10 Italian Night 7 Judicial Retention Plebiscite 11 Nominations – DCBA Board of Directors 12 Press Club 6 Rise to the Occasion! 13 N.B. LEGAL JOURNAL EARLY DEADLINE AUGUST 30TH @ NOON FOR ISSUE DATED SEPTEMBER 10TH DELAWARE COUNTY LEGAL JOURNAL NOTICESDELAWARE TO THE BAR COUNTY LEGALVol. 108 JOURNALNo. 35 8/27/21 USPS 151-960 The Official Legal Newspaper of Delaware County — Reporting the Decisions of the Courts of Delaware County The 32nd Judicial District of Pennsylvania OWNED AND PUBLISHED BY DELAWARE COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION 2021 OFFICERS DIRECTORS Karen E. Friel Robert F. Kelly, Jr. Michael H. Hill President Craig B. Huffman Gregory Hurchalla Carrie A. Woody Past Presidents Steven R. Koense President Elect Jennifer L. Galante John P. McBlain Patrick T. Daley President, Young Lawyers’ Theresa Flanagan Murtagh Vice President Section Rachael L. Kemmey Lorraine M. Ramunno Jennifer M. DiPillo Daniel J. Siegel Treasurer Patricia H. Donnelly Michael J. Davey Hon. Frank T. Hazel Recording Secretary Patrick T. Henigan Mary J. Walk Corresponding Secretary Maureen Henry LEGAL JOURNAL COMMITTEE Ronald A. Amarant Hon. William C. Mackrides Editor: Matthew J. Bilker Jennifer H. -

Song-Book.Pdf

1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Rockin’ Tunes Ain’t No Mountain High Enough 6 Sherman The Worm 32 Alice The Camel 7 Silly Billy 32 Apples And Bananas 7 Swimming, Swimming 32 Baby Jaws 8 Swing On A Star 33 Bananas, Coconuts & Grapes 8 Take Me Out To The Ball Game 33 Bananas Unite 8 The Ants Go Marching 34 Black Socks 8 The Bare Necessities 35 Best Day Of My Life 9 The Bear Song 36 Boom Chicka Boom 10 The Boogaloo 36 Button Factory 11 The Cat Came Back 37 Can’t Buy Me Love 11 The Hockey Song 38 Day O 12 The Moose Song 39 Down By The Bay 12 The Twinkie Song 39 Don’t Stop Believing 13 The Walkin’ Song 39 Fight Song 14 There’s A Hole In My Bucket 40 Firework 15 Three Bears 41 Forty Years On An Iceberg 16 Three Little Kittens 41 Green Grass Grows All Around 16 Through The Woods 42 Hakuna Matata 17 Tomorrow 43 Here Little Fishy 18 When The Red, Red Robin 43 Herman The Worm 18 Yeah Toast! 44 Humpty Dump 19 I Want It That Way 19 If I Had A Hammer 20 Campfire Classics If You Want To Be A Penguin 20 Is Everybody Happy? 21 A Whole New World 46 J. J. Jingleheimer Schmidt 21 Ahead By A Century 47 Joy To The World 21 Better Together 48 La Bamba/Twist And Shout 22 Blackbird 49 Let It Go 23 Blowin’ In The Wind 50 Mama Don’t Allow 24 Brown Eyed Girl 51 M.I.L.K. -

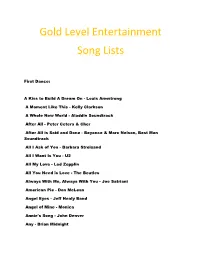

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour -

Creative Grantmaking

WINTER 2018 VOLUME XXXII ISSUE 1 THE VISIT OUR WEBSITE : www.catholicfoundation.com Creative Grantmaking ave you ever thought about facilitating creative grantmaking grantmaking with a creative flair? opportunities that truly reflect the specific H Last year, The Catholic philanthropic dreams you would like to see Foundation distributed more than 1,600 grants realized.” totaling nearly $18.3 million, with the vast Ray and Ruth Hemmig have partnered majority from funds established by individuals with The Catholic Foundation for their or families who determined the philanthropic charitable giving for more than a decade. intent for the grant recommendation. There They have recommended a number of is a huge need for general operating support creative grant ideas, including funding a for nonprofit organizations, and that is where professorship at the University of Texas at many grants are directed. However, there are Dallas (UTD) in honor of a dear friend and also opportunities to add some innovation to respected leader. When Ray owned a public conducted research and presented innovative your giving. company, he began working closely with concepts that truly resonated with Ray. “We’d like donors to know they can also Dr. Constantine “Connie” Konstans at “When we raised this idea as a possible make a difference with a different approach UTD’s Naveen Jindal School of Management recommendation from the fund we to their grantmaking,” said Vice President of on adult education opportunities for the established with The Catholic Foundation, Development Cheryl Mansour. “Our staff at executives serving on his corporate board. they didn’t blink at the challenge. -

Summer Camp Song Book

Summer Camp Song Book 05-209-03/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Numbers 3 Short Neck Buzzards ..................................................................... 1 18 Wheels .............................................................................................. 2 A A Ram Sam Sam .................................................................................. 2 Ah Ta Ka Ta Nu Va .............................................................................. 3 Alive, Alert, Awake .............................................................................. 3 All You Et-A ........................................................................................... 3 Alligator is My Friend ......................................................................... 4 Aloutte ................................................................................................... 5 Aouettesky ........................................................................................... 5 Animal Fair ........................................................................................... 6 Annabelle ............................................................................................. 6 Ants Go Marching .............................................................................. 6 Around the World ............................................................................... 7 Auntie Monica ..................................................................................... 8 Austrian Went Yodeling .................................................................