Caragiale and Gusti: Sociological Intersections CARAGIALE and GUSTI: SOCIOLOGICAL INTERSECTIONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Critical Appreciations Concerning the Dramaturgy and Sketches of I

Annals of the „Constantin Brâncuși” University of Târgu Jiu, Letter and Social Science Series, 4/2015 CRITICAL APPRECIATIONS CONCERNING THE DRAMATURGY AND SKETCHES OF I. L. CARAGIALE Associate Professor Ph D, Mirabela Rely Odette CURELAR “Constantin Brâncuşi” University of Târgu-Jiu ABSTRACT: LITERARY CRITICISM AS FROM POMPILIU CONSTANTINESCU, G. CALINESCU VIANU TUDOR SERBAN CIOCULESCU, ALEXANDRU PIRU AND CONTINUING SILVIAN IOSIFESCU ION CONSTANTINESCU, V. FANACHE AND OTHERS AT LEAST AS VALUABLE FIXES CARAGIALE'S WORK AND CHARACTER BALKAN PERSPECTIVE CARAGIALE AUTHOR APPRECIATED AS A MASTER OF HUMOR BY USING PHILOSOPHICAL GESTURES. THE WRITER COMES BACK WITH "POLITICS", STATED TALKING BANTER HIS GENIUS CONSISTING OF MUCALIT, WHICH AWAKENS THE ADMIRATION. IN LITERARY CRITICISM IN THE LAST QUARTER CENTURY, CARAGIALE'S CHARACTER EMERGES AS A "LEGENDARY" CHARACTER, A KIND OF URBAN PĂCALĂ. KEY WORDS: CRITICISM, THE MORALIST, TYPOLOGICAL CHARACTER, ENIGMATICAL COMIC, COMIC ATMOSPHERE. Caragiale's work projects a real world, described in terms of often unreal or concealed by its weaknesses in order to contemplation of reality with a self-ironic elegance. Caragiale may be defined as a moralist, that a writer concerned about the man's character and morals in his social relations "political animal," as Aristotel understood him the human in the city (polis). From this derives political leader of his trilogy thread comic: A Stormy Night, Cone Leonida face to Reactionaries and The Lost Letter. Caragiale views man in society no longer sees in nature, man sees in the interdependence of its social, but not interdependent cosmic human of the mountains, the hills, the plains of the Danube, by the sea, and so on It is sensitive to social categories, clearly distinguishes categorical language, captures the conflicting interests, connections and conflicts of ideas in the social life. -

Book of Abstracts

ANNALES UNIVERSITATIS APULENSIS. SERIES PHILOLOGICA, no. 17, issue 3 / 2016 STUDII DE CULTURĂ ŞI LITERATURĂ / CULTURE AND LITERATURE STUDIES EDITORIALUL ŞI LITERATURA: STRATEGII ŞI TEHNICI Drd. DRAGOȘ ZOLTAN BAKO Universitatea „Lucian Blaga” din Sibiu Abstract: The persuasiveness that a journalist can achieve in relation with his readers, through writing, is invariably connected to the act of creation. The linguistic strategies have determined a classification according to the type of language used in the editorials of the following journalists: an intellectualised language in Andrei Pleşu’s case (given by the value and aim of the addressability), a pamphlet language in the case of Mircea Dinescu, a raw language specific to Cristian Tudor Popescu, cautious language in Mircea Cărtărescu’s case. Starting from the idea that the image constructs itself in the form of analysis, somewhere between symbol and sign (Durand, 1977:34), the editorial often uses so-called systems of image, which know two fundamental types of expression: ideatic and mediatic (LULL, 1999: 15). Thus, the images are constructed by resorting to the “vibrant forms” of reality, that are sometimes shocking, a form of the interweaving of the literary and the cultural within the publicistic text. Keywords: editorial; persuasiveness; language; image; publicistic; literary PRIMELE ARTICOLE ROMÂNEȘTI DESPRE POSTMODERNISM Drd. ROBERT CINCU Universitatea „Babeș-Bolyai” Cluj-Napoca Abstract: The paper analyses some of the first Romanian theoretical articles focused on the topic of postmodernism. My aim is to identify common features among these texts and to establish their role in the larger context of Romanian culture in general. I will focus mainly on two texts dating from the early 70’s, respectively from the early 80’s (authors: Andrei Brezianu, Nicolae Manolescu). -

Serban Cioculescu

Viaţa lui I.L. Caragiale Şerban Cioculescu (7 septembrie 1902 – 25 iunie 1988) este unul dintre cei mai importanţi critici şi istorici ai literaturii române. A absolvit Facultatea de Litere şi Filozofie la Bucureşti şi a studiat filologia romanică la Sorbona şi la École Pratique des Hautes Études din Paris. Publicist redutabil, a colaborat la Vremea, Vitrina literară, România literară, Revista Fundaţiilor Regale, Lumea, Viaţa Românească, Gazeta literară, Cahiers roumains d’ études litteraires, Manuscrip tum. A editat revistele Viaţa univer - sitară şi Kalende, alături de VIadimir Streinu, Pompiliu Constantinescu şi Tudor Şoimaru. A fost redactor-şef la Viaţa Românească între 1965 şi 1967. În 1935 editează Corespondenţa dintre I.L. Caragiale şi Paul Zarifopol (1905– 1912), urmată de: Viaţa lui I.L. Caragiale (1940; ed. a II-a, revăzută, 1969), Aspecte lirice contemporane (1942), Istoria literaturii române moderne, vol. I, în colaborare cu Vl. Streinu şi T. Vianu (1944; ed. a II-a, 1985), Dimitrie Anghel. Viaţa şi opera (1945), Introducere în poezia lui Tudor Arghezi (1946; ed. revăzută, 1971), Curs de istoria literaturii române moderne. Literatura militantă (1947), Varietăţi critice (1966), I.L. Caragiale (1967), Medalioane franceze (1971), Aspecte literare contemporane. 1932–1947 (1972), Itinerar critic, vol. I–V (1973–1989), Amintiri (1973; ed. a II-a, 1981), Caragialiana (1974; ed. a II-a, 1987), Viaţa lui I.L. Caragiale. Caragialiana (1977), Pro - zatori români. De la Mihail Kogălniceanu la Mihail Sadoveanu (1977), Poeţi români (1982), Introducere în opera lui Dimitrie Anghel (1983), Introduction à la poésie de Tudor Arghezi (1983), Argheziana (1985), Eminesciana (1985), Dialoguri literare (1987). ŞERBAN CIOCULESCU Viaţa lui I.L.Caragiale Redactor: Anca Lăcătuş Coperta: Ioana Nedelcu Tehnoredactor: Manuela Măxineanu Corector: Cristina Jelescu DTP: Radu Dobreci Tipărit la C.N.I. -

Textual Transpositions and Identity Games in I.L. Caragiale's Late

Textual Transpositions and Identity Games in I.L. Caragiale’s Late Writings ∗ Doris MIRONESCU Key-words: cultural identity , irony , ambivalence , Balkan literature , textual transposition The first critical edition of I.L. Caragiale’s Works , initiated by Paul Zarifopol in 1930 at “Cultura Na ţional ă” Publishing House, opens with the famous photo of the author taken in Berlin, in which Caragiale sits cross-legged, oriental-style, on a similarly themed rug, dressed in Balkanic garb, wearing a fez and white long socks, posing evidently for the camera with his chin resting on his closed hand and his eyes gazing intently to the right. But, even in these carefully asorted Levantine surroundings, one cannot fail to notice that behind the posing artist there is a heavily stacked library, filled with thick manuscripts that seem to overflow. The image is, therefore, twice symbolic: on the one hand, because in it Caragiale seems to claim to be returning to the “ethnic roots” that he often reclaimed polemically, orally and in writing, precisely to contradict the partisans of a ridiculous and violent Romanian nationalism; on the other hand, because this return takes place in the foreground of a library, or better yet of literature 1. Caragiale’s entire work is characterized by a frequent use of intertextual procedures, but these appear to become even more often in his last period of creation, in Berlin (1905–1912). The critics have long remarked that “Caragiale drew a character face for himself” (Tomu ş 1977: 340) but he exploited it especially now, in the later years at Berlin, to present himself under the largely known name “nenea Iancu” ( Ţal!.. -

Călătorie Prin Arhiva Muzeului Naţional Al Literaturii Române Din Bucureşti

CĂLĂTORIE PRIN ARHIVA MUZEULUI NAŢIONAL AL LITERATURII ROMÂNE DIN BUCUREŞTI Ioana VASILOIU Muzeul Naţional al Literaturii Române, Bucureşti [email protected] Abstract: The National Museum of Romanian Literature Archive contains a rich heritage represented by manuscripts, letters, documents, original photographs, memorial items, and old Romanian books or periodicals. A journay into the archive of this public institution of culture, unique through its heritage value, is similar to an excursus into the deep memory of the history of literature, but also in the history of the European cultural values and, why not, an itinerary in the consciousness of humanity. Keywords: archive, manuscript, heritage, collection, museum, cultural memory Arhiva Muzeului Naţional al Literaturii Române din Bucureşti este un palimpsest. Ea conţine un bogat patrimoniu reprezentat de manuscrise (în formă definitivă sau variante), scrisori şi acte, fotografii originale, obiecte memoriale ale celor mai importanţi scriitori români, dar şi de cărţi vechi româneşti (unele cu dedicaţii, altele având însemnări de lectură) sau publicaţii periodice din secolele XIX şi XX. O călătorie în arhiva acestei instituţii publice de cultură, unică prin valoarea patrimoniului său, este un excurs în memoria profundă a istoriei literaturii române, dar şi în istoria valorilor culturale europene şi, de ce nu, un itinerar în conştiinţa umanităţii. Ideea constituirii unei arhive care să adune la un loc manuscrisele literare rămase de la scriitori a aparţinut editorului eminescian Dumitru Panaitescu Perpessicius, căruia i se datorează şi înfiinţarea Muzeului, la 1 iulie 1957. De la această dată arhiva s-a îmbogăţit enorm (fie prin donaţii primite de la scriitori sau de la descendenţii scriitorilor, fie prin oferte plătite) încât, astăzi, ea deţine peste 300.000 de piese structurate în 300 de colecţii (secolele XV-XX) de autor. -

Proquest Dissertations

LITERATURE, MODERNITY, NATION THE CASE OF ROMANIA, 1829-1890 Alexander Drace-Francis School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD June, 2001 ProQuest Number: U642911 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642911 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT The subject of this thesis is the development of a literary culture among the Romanians in the period 1829-1890; the effect of this development on the Romanians’ drive towards social modernization and political independence; and the way in which the idea of literature (as both concept and concrete manifestation) and the idea of the Romanian nation shaped each other. I concentrate on developments in the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (which united in 1859, later to form the old Kingdom of Romania). I begin with an outline of general social and political change in the Principalities in the period to 1829, followed by an analysis of the image of the Romanians in European public opinion, with particular reference to the state of cultural institutions (literacy, literary activity, education, publishing, individual groups) and their evaluation for political purposes. -

Proquest Dissertations

c A BIOGRAPHY OF MIRCEA ELIADE'S SPIRITUAL AND INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT FROM 1917 TO 1940 by Dennis A. Doeing Thesis presented to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Ph.D. in Religious Studies 0O*BIBf/ v [Ml UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA OTTAWA, CANADA, 1975 0 L.BRAKttS A CjD.A. Doeing, Ottawa, Canada, 1975 UMI Number: DC53829 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53829 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am very grateful to Dr. Reinhard Pummer, of the Department of Religious Studies of the University of Ottawa, who provided direc tion for this research. His insistence on exactness and coherency led to many revisions in the text, and his valuable comments helped me to realize the purpose and extent of this work. I am further indebted to Mr- Georges Tissot, of the University of Ottawa, and to Dr. Edward Zimmermann, of Ganisius College in Buffalo, for sug gestions concerning the general style and readability of the dis sertation. -

Arhive Personale Şi Familiale

Arhive personale şi familiale Vol. II Repertoriu arhivistic Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei ISBN 973-8308-08-9 Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei ARHIVELE NAŢIONALE ALE ROMÂNIEI Arhive personale şi familiale Vol. II Repertoriu arhivistic Autor: Filofteia Rînziş Bucureşti 2002 Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei ● Redactor: Alexandra Ioana Negreanu ● Indici de arhive, antroponimic, toponimic: Florica Bucur ● Culegere computerizată: Filofteia Rînziş ● Tehnoredactare şi corectură: Nicoleta Borcea ● Coperta: Filofteia Rînziş, Steliana Dănăilescu ● Coperta 1: Scrisori: Nicolae Labiş către Sterescu, 3 sept.1953; André Malraux către Jean Ajalbert, <1923>; Augustin Bunea, 1 iulie 1909; Alexandre Dumas, fiul, către un prieten. ● Coperta 4: Elena Văcărescu, Titu Maiorescu şi actriţa clujeană Maria Cupcea Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei CUPRINS Introducere ...................................................................... 7 Lista abrevierilor ............................................................ 22 Arhive personale şi familiale .......................................... 23 Bibliografie ...................................................................... 275 Indice de arhive ............................................................... 279 Indice antroponimic ........................................................ 290 Indice toponimic............................................................... 339 Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei Arhivele Nationale ale Romaniei INTRODUCERE Cel de al II-lea volum al lucrării Arhive personale şi familiale -

Mateiu Caragiale, Corespondenţa La Subjectivité Dans La Nouvelle Identité De La Science Économique Européenne Ecaterina

4 366 / 201 8() ISSN 1220 -6350 ISSN 1220 -6350 9 771220 635006 9 771220 635006 Mateiu Caragiale, Corespondenţa de Eugen Simion La subjectivité dans la nouvelle identité de la science économique européenne de Jaime Gil Aluja Ecaterina Andronescu: „Cultura şi învăţământul, sub lupă“ Fănuş Neagu, scriitor baroc de Aluniţa Cofan Faţa umană a civilizaţiilor de Caius Traian Dragomir Nr. 4 ( 366 ) / 201 8 Mihaela BURUGĂ secretariat de re d acţie CUPRINS 4/2018 FRAGMENTE CRITICE Eugen SIMION: Mateiu Caragiale. Corespondenţa Mateiu Caragiale. Correspondence . 3 A GÂNDI EUROPA Jaime Gil ALUJA: Subiectivitatea în noua identitate a ştiinţei economice europene La subjectivité dans la nouvelle identité de la science économique européenne . 10 INTERVIU Ecaterina ANDRONESCU: Cultura şi învăţământul sub lupă, interviu de Florian Saiu Culture and Education under the magnifying glass, Florian Saiu in dialogue with Ecaterina Andronescu . 17 SCRISOARE DE LA KÖLN Nicolae CORBEANU: Cine mai votează? Adolescenţii germani şi alegerile Who is voting? German Teens and Elections . 32 COMENTARII Aluniţa COFAN: Fănuş Neagu, scriitor baroc Fănuş Neagu, baroque writer . 35 Mădălina PETREA: Perspectiva realismului mitologic din Îngerul a strigat de Fănuş Neagu The Perspective of Mythological Realism in Îngerul a strigat by Fănuş Neagu. 41 Caius Traian DRAGOMIR: Faţa umană a civilizaţiilor The Human Face of Civilization . 49 1 Lucian CHIŞU, Viorica Ana CHIȘU: Comunicarea online în instituţii de învăţământ superior româneşti şi europene (II) Online communication in institutions of Romanian and European higher education (II) . 53 EMINESCU Valentin COȘEREANU: Cronologie Eminescu (V) Chronology of Eminescu (V) . 65 Ilustrăm acest număr cu lucrări ale artistului plastic Ștefan Popescu (1872-1948) 2 Fragmente critice Eugen SIMION Mateiu Caragiale. -

REMUS ZĂSTROIU, Adevărul Literar Şi Artistic

DINATEliERUL UNUI DICŢIONAR AL LI1ERATURlJROMiÎNE* ADEVĂRUL LITERAR ŞI ARTISTIC REMUSZĂSTROru Revista a apărut la Bucureşti, săptămânal,de la 28 noiembrie 1920 până la 28 mai 1939. Este seria a doua a periodicului.Adevărul literar" (13 septembrie 1893 - 13 februarie 1895),dar nu mai are regimul unui suplimental cotidianului "Adevărul", ci trebuie socotită o publicaţie independentă, editată de gmpul de presă constituitîn jurul ziaruluititular, după ce, în august 1920, C. Mille renunţă la proprietateaasupra acestuia.Primele numere au ieşit sub conducereascriitomlui şi gazetaruluiEmil D. Fagure,până în mai 1921,când la direcţievine un alt scriitor şi gazetar cunoscut, A. de Herz. Pentru anii de început (1920-1925), structura şi aspectulgrafic rămân cele stabilite de Fagure, cu unele schimbări- rubrici,titulari de cronici etc. - cauzate de retragerea unor redactori sau colaboratorişi venirea altora noi. A. de Herz renunţă la direcţia revistei În prima parte a anului 1925 şi locul lui este luat de un tânăr gazetar şi prozator,Mihail Sevastos,format la Iaşi, în cercul "Vieţii româneşti", la a cărui revistă ucenicise. Sevastos reorganizează A.I.a., îi dă o înfăţişare grafică modernă şi iniţiază rubrici noi, pe care le încredinţează unor scriitori consacraţi (T. Arghezi, E. Lovinescu ş.a.) sau altora aflaţi la începutul carierei (G. Călinescu, AI. O. Teodoreanu ş.ă.) Nu se va modifica Însă orientarea politică şi socială, situată în continuarea aceleia democratice, imprimate de C. Mille, şi nici interesul neîntrerupt pentru viaţa culturală autohtonă şi, în primul rând, pentru literatura română şi pentru scriitorii care Încep să se impunădupă războiulmondial. Un articol de fond, care trece de obiceiîn revistă evenimenteleimportante ale unei săptămâni- fie politice, fie culturale-, deschidein mod obişnuitpagina întâi şi este semnat de ziarişti sau scriitori proveniţi din redacţia "Adevărului"sau din cercul celor apropiaţisub raportulideilor: C. -

Mircea Eliade (1938)

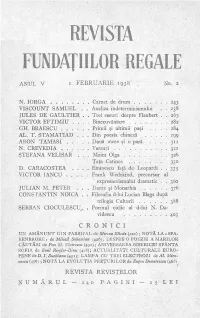

REV1STA FUNDATIILOR REGALE ANUL V FEBRUARIE 1938 NR. 2 . k N. IORGA Carnet de drum 243 VISCOUNT SAMUEL . Analiza indeterminismului . 258 JULES DE GAULTIER . Trei eseuri despre Flaubert . 265 VICTOR EFTIMIU . , Binecuvantare 282 GH. BRAESCU Primii i ultimii pasi . 284 AL. T. STAMATIAD . Din poesia chinezd 299 ARON TAMASI Douä mere si o par5 . 311 N. CREVEDIA . Versuri 321 STEFANA VELISAR . Maica Olga 326 Tata Catinca 330 D. CARACOSTEA . .-' . Eminescu fatà de Leopardi . 335 VICTOR IANCU . Frank Wedekind, precursor al expresionismului dramatic . 360 JULIAN M. PETER . Dante si Monarhia 376 CONSTANTIN NOICA . Filosofia d-lui Lucian Blaga dupà trilogia Culturii ^ SERBAN CIOCULESCU, . Poemul ciclic al d-lui N. Da- videscu 405 CRONICI UN AMANUNT DIN PARSIFAL de Mircea Eliade (422) ; NOTA LA .2 SPA- RENBROKE » de Mihail Sebastian (426); DESPRE 0 POEZIE A MARILOR CAUTARI de Pan M. Vizirescu (431) ; ANIVERSAREA BISERICEI SFANTA SOFIA de Emil Riegler-Dinu (446); ACTUALITATI CULTURALE EURO- PENE de D. I. Suchianu (451); LAMPA CU TREI ELECTROZI de Al. Miro- nescu (456) ; NOTA LA EVOLUTIA PRETURILOR de Eugen Demetrescu (46o) REVISTA REVISTELOR N U M A.RUL 2 4 o P A G I N I 2 5 LEI r REVISTA FUNDATIILOR REGALE REVISTA LUNARA DE LITERATURA, ARTA CULTURA GENERALA COMITETUL DE DIREC TIE! I. AL. BRATESCU-VOINESTI, 0. GOGA, D. GUSTI, E. RACOVITA, C. RADULESCU-MOTRU, I. SIMIONESCU Redactor fef: Redactoril PAUL ZARIFOPOL CAMIL PETRESCU (1.I 1.V.1934) RADU CIOCULESCU REDACTIAmilmmiliumminummiffillionolumnimillimuffintil BUCURESTI III 39, BULEVARDUL LASCAR CATARGI, 39 TELEFON 2 -40 -70 AD MINISTRATIA CENTRALA EDITURILOR FUNDATIILOR REGALE 22, STRADA LIPSCANI, 22 TELEFON 5 - 37 - 77 11111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111I ABONAMENTUL ANUAL LEI 3 o o PENTRU INSTITUTII 51 INTREPRINDERI PARTICULARE LEI L000 EXEMPLARUL 25 LEI , CONT CEC POSTAL NR, 1210 ABONAMENTELE SE POT FACE ACHITA PRIN ORICE . -

Tissus Et Accessoires Oubliés

LILIANA BURLACU TISSUS ET ACCESSOIRES OUBLIÉS. DE LA PANOPLIE VESTIMENTAIRE DʼUN ÉCRIVAIN « SENTIMENTAL » « La tenue absolument sans prétention : où il y de gêne, il nʼy pas de plaisir »1. Rien ne pourrait mieux caractériser lʼopinion sur la mode et lʼhabillement de lʼauteur de Momente [Moments] que « le dicton favori » de la « gracieuse madame Guvidi », le personnage féminin de sa nouvelle Om cu noroc! [Homme fortuné !]. Dʼune trajectoire rectiligne, celle-ci favorise, en exclusivité, le confort, à partir duquel Caragiale ne sʼécarte ni même dans la jeunesse, pendant son mandat dʼinspecteur, étant surpris, un jour de grand froid, avec lʼhabit emprunté ni vers la fin de sa vie, quand, à Berlin, « pour ses vêtements il nʼa aucune préoccupation, et il aimait ses habits vieillis »2. Il est possible que ce soit ici la raison pour laquelle la garde-robe du père nʼa jamais correspondu aux exigences vestimentaires du fils, Mateiu Caragiale. Pour sa flanelle « déchirée aux coudes » et pour ses « pantalons longs et serrés quʼil appelait “de cavalier” »3, Caragiale ressent le même attachement que celui de Diderot pour sa vieille robe de chambre4. Lʼauteur ne ressemble pourtant pas à son personnage réformateur du récit Reformă...[Réforme], Mihalache Cogălniceanu, qui, en privé, « il faut le savoir, nʼa pas coutume de porter ni robe de chambre, ni pantoufles »5. Au-delà de son caractère anecdotique, lʼemprunt des deux attributs de lʼintimité, la robe de chambre et les pantoufles, par le célibataire Caragiale, pendant la visite quʼil fait à lʼactrice Amelie Welner en absence de son mari, lʼacteur Constantin Nottara, ne peut que soutenir lʼhypothèse.