Edward B. Lewis 1918–2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIHAA Summer 1993

The Newsletter of the NIH Alumni Association Summer 1993 Vol. 5, No . 2 date Nobel Laureate Harold Varmus Nominated as 14th NIH Director Ruth Kirschstein Named Acting Director President Clinton on A ug. 3 announced his intention to nominate Dr. Harold Eliot Varmus as the 14th director of th e National Institutes of Health. A Senate confirmation process must precede Yarmus· taking over leadership of the institutes. Winner of the Nobel Prize in 1989 for his work in cancer research. Va1111us. 53. is a professor of microbi ology. biochemistry. and biophysics. and the American Cancer Society pro fessor vfmoh:cu/ur >1iro/O£)' iJI l/Je Uni versity of California, San Francisco. He is a leader in the stu dy of cancer causing genes called "oncogenes," and an intemationall-y fecogni:z.ed authof\t-y Dr. Ruth l. Kirschsteln , acting NIH director on retroviruses. the viruses that cause Dr. Harold E. Varmus , direclor-designale AIDS and many cancers in animnl.. FIC 25 Years Old In '93 Thirty-eight-year NIH veteran Dr. Research Festival '93 Schedule Ruth Kirschstein. director of NIGM S Scholars-in-Residence (See Director p. 6) NIHAA Members Invited Program Celebrates To Alumni Symposium In This Issue Tile fas\ morning ofNCH Rc:-.c;\rch Nursing cell/er /J1·1·111111•s Festival '93-Monday. Sept. 20-has This year. the Fogarty Intern ational 17th i11s1it11tc• 111 NII/ p. ? been designated National lnsritute of Center (FIC) is 25 years old . T he cen Greeri11gs from 1/,11 1w11• NII /AA prl'sidt'lll. Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Tltolll(IS .I. -

Advertising (PDF)

Neuroscience 2013 SEE YOU IN San Diego November 9 – 13, 2013 Join the Society for Neuroscience Are you an SfN member? Join now and save on annual meeting registration. You’ll also enjoy these member-only benefits: • Abstract submission — only SfN members can submit abstracts for the annual meeting • Lower registration rates and more housing choices for the annual meeting • The Journal of Neuroscience — access The Journal online and receive a discounted subscription on the print version • Free essential color charges for The Journal of Neuroscience manuscripts, when first and last authors are members • Free online access to the European Journal of Neuroscience • Premium services on NeuroJobs, SfN’s online career resource • Member newsletters, including Neuroscience Quarterly and Nexus If you are not a member or let your membership lapse, there’s never been a better time to join or renew. Visit www.sfn.org/joinnow and start receiving your member benefits today. www.sfn.org/joinnow membership_full_page_ad.indd 1 1/25/10 2:27:58 PM The #1 Cited Journal in Neuroscience* Read The Journal of Neuroscience every week to keep up on what’s happening in the field. s4HENUMBERONECITEDJOURNAL INNEUROSCIENCE s4HEMOSTNEUROSCIENCEARTICLES PUBLISHEDEACHYEARNEARLY in 2011 s )MPACTFACTOR s 0UBLISHEDTIMESAYEAR ,EARNMOREABOUTMEMBERAND INSTITUTIONALSUBSCRIPTIONSAT *.EUROSCIORGSUBSCRIPTIONS *ISI Journal Citation Reports, 2011 The Journal of Neuroscience 4HE/FlCIAL*OURNALOFTHE3OCIETYFOR.EUROSCIENCE THE HISTORY OF NEUROSCIENCE IN AUTOBIOGRAPHY THE LIVES AND DISCOVERIES OF EMINENT SENIOR NEUROSCIENTISTS CAPTURED IN AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL BOOKS AND VIDEOS The History of Neuroscience in Autobiography Series Edited by Larry R. Squire Outstanding neuroscientists tell the stories of their scientific work in this fascinating series of autobiographical essays. -

Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology

COLD SPRING HARBOR SYMPOSIA ON QUANTITATIVE BIOLOGY VOLUME XL COLD SPRING HARBOR SYMPOSIA 0 N Q UA NTITA T1VE BIOLO G Y Founded in 1933 by REGINALD G. HARRIS Director of the Biological Laboratory 1924 to 1936 Volume I (1933).Surface Phenomena Volume II (1934) Aspects of Growth Volume III (1935) Photochemical Reactions Volume IV (1936) Excitation Phenomena Volume V (1937) Internal Secretions Volume VI (1938) Protein Chemistry Volume VII (1939) Biological Oxidations Volume VIII (1940) Permeability and the Nature of Cell Membranes Volume IX (1941) Genes and Chromosomes: Structure and Organization Volume X (1942) The Relation of Hormones to Development Volume XI (1946) Heredity and Variation in Microorganisms Volume XII (1947) Nucleic Acids and Nucleoproteins Volume XIII (1948) Biological Applications of Tracer Elements Volume XIV (1949) Amino Acids and Proteins Volume XV (1950) Origin and Evolution of Man Volume XVI (1951) Genes and Mutations Volume XVII (1952) The Neuron Volume XVIII (1953) Viruses Volume XIX (1954) The Mammalian Fetus: Physiological Aspects of Development Volume XX (1955) Population Genetics: The Nature and Causes of Genetic Variability in Population Volume XXI (1956) Genetic Mechanisms: Structure and Function Volume XXII (1957) Population Studies: Animal Ecology and Demography Volume XXIII (1958) Exchange of Genetic Material: Mechanism and Consequences Volume XXIV (1959) Genetics and Twentieth Century Darwinism Volume XXV (1960) Biological Clocks Volume XXVI (1961) Cellular Regulatory Mechanisms Volume XXVII (1962) Basic -

A Correlation of Cytological and Genetical Crossing-Over in Zea Mays. PNAS 17:492–497

A CORRELATION OF CYTOLOGICAL AND GENETICAL CROSSING-OVER IN ZEA MAYS HARRIET B. CREIGHTON BARBARA MCCLINTOCK Botany Department Cornell University Ithaca, New York Creighton, H., and McClintock, B. 1931 A correlation of cytological and genetical crossing-over in Zea mays. PNAS 17:492–497. E S P Electronic Scholarly Publishing http://www.esp.org Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project Foundations Series –– Classical Genetics Series Editor: Robert J. Robbins The ESP Foundations of Classical Genetics project has received support from the ELSI component of the United States Department of Energy Human Genome Project. ESP also welcomes help from volunteers and collaborators, who recommend works for publication, provide access to original materials, and assist with technical and production work. If you are interested in volunteering, or are otherwise interested in the project, contact the series editor: [email protected]. Bibliographical Note This ESP edition, first electronically published in 2003 and subsequently revised in 2018, is a newly typeset, unabridged version, based on the 1931 edition published by The National Academy of Sciences. Unless explicitly noted, all footnotes and endnotes are as they appeared in the original work. Some of the graphics have been redone for this electronic version. Production Credits Scanning of originals: ESP staff OCRing of originals: ESP staff Typesetting: ESP staff Proofreading/Copyediting: ESP staff Graphics work: ESP staff Copyfitting/Final production: ESP staff © 2003, 2018 Electronic Scholarly Publishing Project http://www.esp.org This electronic edition is made freely available for educational or scholarly purposes, provided that this copyright notice is included. The manuscript may not be reprinted or redistributed for commercial purposes without permission. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

2004 Albert Lasker Nomination Form

albert and mary lasker foundation 110 East 42nd Street Suite 1300 New York, ny 10017 November 3, 2003 tel 212 286-0222 fax 212 286-0924 Greetings: www.laskerfoundation.org james w. fordyce On behalf of the Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation, I invite you to submit a nomination Chairman neen hunt, ed.d. for the 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards. President mrs. anne b. fordyce The Awards will be offered in three categories: Basic Medical Research, Clinical Medical Vice President Research, and Special Achievement in Medical Science. This is the 59th year of these christopher w. brody Treasurer awards. Since the program was first established in 1944, 68 Lasker Laureates have later w. michael brown Secretary won Nobel Prizes. Additional information on previous Lasker Laureates can be found jordan u. gutterman, m.d. online at our web site http://www.laskerfoundation.org. Representative Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards Program Nominations that have been made in previous years may be updated and resubmitted in purnell w. choppin, m.d. accordance with the instructions on page 2 of this nomination booklet. daniel e. koshland, jr., ph.d. mrs. william mccormick blair, jr. the honorable mark o. hatfied Nominations should be received by the Foundation no later than February 2, 2004. Directors Emeritus A distinguished panel of jurors will select the scientists to be honored. The 2004 Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards will be presented at a luncheon ceremony given by the Foundation in New York City on Friday, October 1, 2004. Sincerely, Joseph L. Goldstein, M.D. Chairman, Awards Jury Albert Lasker Medical Research Awards ALBERT LASKER MEDICAL2004 RESEARCH AWARDS PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION OF THE AWARDS The major purpose of these Awards is to recognize and honor individuals who have made signifi- cant contributions in basic or clinical research in diseases that are the main cause of death and disability. -

Transforming Lives

Brooklyn College Foundation Annual Report 2007–2008 Transforming Lives The First Step The doors to Brooklyn College are the doors to opportunity. Compared with other institutions of higher education, a great many of our students shoulder substantial responsibilities, and many are the first in their family to attend college. Diverse in background, interests, and ambition, they share the certainty that higher education is the way to a productive and rewarding future. For many, that future will be secured with the help of the Brooklyn College Foundation Dear Friends of Brooklyn College For students—past and present—Brooklyn College stands as a gateway to a rewarding life. They come because they want to become effective leaders in their chosen profession and engaged citizens of the world. They come because they have heard of our commitment to academic quality and to helping them reach their goals. This commitment is at the heart of who we are and what we do. We have held firm to this principle throughout my presidency and, as I leave Brooklyn College this summer, I am especially proud of what we have done together to give it life and to sustain it. Last fall, we admitted a freshman class larger and better than the year before and we were joined by forty new faculty members, bringing the number of scholars and artists we have recruited over the last nine years to 273, more than half the teaching faculty and more than we appointed in the previous three decades. We also welcomed a new Provost, Dr. William A. Tramontano, who brings proven leadership in initiating and implementing new academic programs. -

Advertising (PDF)

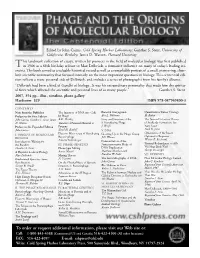

Edited by John Cairns, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; Gunther S. Stent, University of California, Berkeley; James D. Watson, Harvard University his landmark collection of essays, written by pioneers in the field of molecular biology, was first published T in 1966 as a 60th birthday tribute to Max Delbrück, a formative influence on many of today’s leading sci- entists. The book served as a valuable historical record as well as a remarkable portrait of a small, pioneering, close- knit scientific community that focused intensely on the most important questions in biology. This centennial edi- tion reflects a more personal side of Delbrück, and includes a series of photographs from his family’s albums. “Delbrück had been a kind of Gandhi of biology...It was his extraordinary personality that made him the spiritu- al force which affected the scientific and personal lives of so many people.” —Gunther S. Stent 2007, 394 pp., illus., timeline, photo gallery Hardcover $29 ISBN 978-087969800-3 CONTENTS Note from the Publisher The Injection of DNA into Cells Bacterial Conjugation Quantitatitve Tumor Virology Preface to the First Edition by Phage Elie L. Wollman H. Rubin John Cairns, Gunther S. Stent, James A.D. Hershey Story and Structure of the The Natural Selection Theory D. Watson Transfer of Parental Material to λ Transducing Phage of Antibody Formation; Ten Preface to the Expanded Edition Progeny J. Weigle Years Later John Cairns Lloyd M. Kozloff V. DNA Niels K. Jerne Electron Microscopy of Developing Growing Up in the Phage Group Cybernetics of the Insect I. ORIGINS OF MOLECULAR Optomotor Response BIOLOGY Bacteriophage J.D. -

Chromosomal Theory and Genetic Linkage

362 Chapter 13 | Modern Understandings of Inheritance 13.1 | Chromosomal Theory and Genetic Linkage By the end of this section, you will be able to do the following: • Discuss Sutton’s Chromosomal Theory of Inheritance • Describe genetic linkage • Explain the process of homologous recombination, or crossing over • Describe chromosome creation • Calculate the distances between three genes on a chromosome using a three-point test cross Long before scientists visualized chromosomes under a microscope, the father of modern genetics, Gregor Mendel, began studying heredity in 1843. With improved microscopic techniques during the late 1800s, cell biologists could stain and visualize subcellular structures with dyes and observe their actions during cell division and meiosis. With each mitotic division, chromosomes replicated, condensed from an amorphous (no constant shape) nuclear mass into distinct X-shaped bodies (pairs of identical sister chromatids), and migrated to separate cellular poles. Chromosomal Theory of Inheritance The speculation that chromosomes might be the key to understanding heredity led several scientists to examine Mendel’s publications and reevaluate his model in terms of chromosome behavior during mitosis and meiosis. In 1902, Theodor Boveri observed that proper sea urchin embryonic development does not occur unless chromosomes are present. That same year, Walter Sutton observed chromosome separation into daughter cells during meiosis (Figure 13.2). Together, these observations led to the Chromosomal Theory of Inheritance, which identified chromosomes as the genetic material responsible for Mendelian inheritance. Figure 13.2 (a) Walter Sutton and (b) Theodor Boveri developed the Chromosomal Theory of Inheritance, which states that chromosomes carry the unit of heredity (genes). -

![Alfred Henry Sturtevant (1891–1970) [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2262/alfred-henry-sturtevant-1891-1970-1-862262.webp)

Alfred Henry Sturtevant (1891–1970) [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Alfred Henry Sturtevant (1891–1970) [1] By: Gleason, Kevin Keywords: Thomas Hunt Morgan [2] Drosophila [3] Alfred Henry Sturtevant studied heredity in fruit flies in the US throughout the twentieth century. From 1910 to 1928, Sturtevant worked in Thomas Hunt Morgan’s research lab in New York City, New York. Sturtevant, Morgan, and other researchers established that chromosomes play a role in the inheritance of traits. In 1913, as an undergraduate, Sturtevant created one of the earliest genetic maps of a fruit fly chromosome, which showed the relative positions of genes [4] along the chromosome. At the California Institute of Technology [5] in Pasadena, California, he later created one of the firstf ate maps [6], which tracks embryonic cells throughout their development into an adult organism. Sturtevant’s contributions helped scientists explain genetic and cellular processes that affect early organismal development. Sturtevant was born 21 November 1891 in Jacksonville, Illinois, to Harriet Evelyn Morse and Alfred Henry Sturtevant. Sturtevant was the youngest of six children. During Sturtevant’s early childhood, his father taught mathematics at Illinois College in Jacksonville. However, his father left that job to pursue farming, eventually relocating seven-year-old Sturtevant and his family to Mobile, Alabama. In Mobile, Sturtevant attended a single room schoolhouse until he entered a public high school. In 1908, Sturtevant entered Columbia University [7] in New York City, New York. As a sophomore, Sturtevant took an introductory biology course taught by Morgan, who was researching how organisms transfer observable characteristics, such as eye color, to their offspring. -

From Controlling Elements to Transposons: Barbara Mcclintock and the Nobel Prize Nathaniel C

454 Forum TRENDS in Biochemical Sciences Vol.26 No.7 July 2001 Historical Perspective From controlling elements to transposons: Barbara McClintock and the Nobel Prize Nathaniel C. Comfort Why did it take so long for Barbara correspondence. From these and other to prevent her controlling elements from McClintock (Fig. 1) to win the Nobel Prize? materials, we can reconstruct the events moving because their effects were difficult In the mid-1940s, McClintock discovered leading up to the 1983 prize*. to study when they jumped around. She genetic transposition in maize. She What today are known as transposable never had any inclination to pursue the published her results over several years elements, McClintock called ‘controlling biochemistry of transposition. and, in 1951, gave a famous presentation elements’. During the years 1945–1946, at Current understanding of how gene at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium, the Carnegie Dept of Genetics, Cold activity is regulated, of course, springs yet it took until 1983 for her to win a Nobel Spring Harbor, McClintock discovered a from the operon, François Jacob and Prize. The delay is widely attributed to a pair of genetic loci in maize that seemed to Jacques Monod’s 1960 model of a block of combination of gender bias and gendered trigger spontaneous and reversible structural genes under the control of an science. McClintock’s results were not mutations in what had been ordinary, adjacent set of regulatory genes (Fig. 2). accepted, the story goes, because women stable alleles. In the term of the day, they Though subsequent studies revealed in science are marginalized, because the made stable alleles into ‘mutable’ ones. -

Sriram, a 2016.Pdf

A mitochondrial ROS signal activates mitochondrial turnover and represses TOR during stress Ashwin Sriram Thesis submitted to the Newcastle University in candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Newcastle University Faculty of Medical Sciences Institute of Cellular and Molecular Biosciences 1 DECLARATION I certify that this thesis is my own work and I have correctly acknowledged the work of collaborators. I also declare that this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree or any other qualification at this or any other university. Ashwin Sriram July 2016 2 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research work was carried out at the Institute for Cell and Molecular Biosciences and the Institute for Ageing, Newcastle University, Campus for Ageing and Vitality, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom under the supervision of Dr. Alberto Sanz. I owe my deepest of gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Alberto Sanz for giving me an opportunity to carry out this research project in his lab under his esteemed guidance. I am deeply indebted to him especially for the confidence that he always placed in me, his encouragement and support throughout the work. He has contributed a lot to my development as a scientist. A special thanks for all the conversations regarding how science “works”. I would also like to thank him for teaching me most of the techniques that have been implemented in this thesis. I am very grateful to Dr. Filippo Scialo for all his support and help with many experiments that are a part of this thesis. I thank him for all the long discussions in the office and during coffee breaks.