Flatin, Bruce A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caritasverband Für Das Bistum Erfurt E.V

Caritasverband für das Bistum Erfurt e.V. Tätigkeitsbericht für den Berichtszeitraum 01.01.2015 - 31.12.2015 der Beratungsinitiative SED-Unrecht der Caritasregion Mittelthüringen in Erfurt und Saalfeld Caritasverband für das Bistum Erfurt e.V. Caritasverband Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Allgemeine Angaben zur Beratungsstelle 3 1.1. Name und Anschrift des Trägers 3 1.2. Namen und Anschriften der Beratungsstellen 3 1.3. Personelle Besetzung im Berichtsjahr, Arbeitszeit/Woche 5 1.4. Finanzierung, fachliche Betreuung und Konzeption des Dienstes 5 2. Beratungsarbeit 6 2.1. Schwerpunkte – Entwicklungen - Veränderungen 6 2.2. Strafrechtliche Rehabilitierung nach StrRehaG 7 2.3. Berufliche Rehabilitierung nach BerRehaG 8 2.4. Verwaltungsrechtliche Rehabilitierung nach VwRehaG 9 2.5. Anträge und Anfragen zur Akteneinsicht in die Stasi-Unterlagen beim Bundesbe- auftragten 10 2.6. Unterstützung bei der Schicksalsaufklärung/Vermisstensuche 10 2.7. Zusammenarbeit mit der Thüringer Anlaufstelle für ehemalige Heimkinder der DDR 11 2.8. Einblicke in unsere Beratungsarbeit 11 3. Statistik 15 3.1. Gesamtübersichten 2015 15 3.2. Mobile Beratung in den Landkreisen und kreisfreien Städten 16 3.3. Beratung von Betroffenen in den Beratungsstellen 17 3.4. Schwerpunkte unserer Arbeit 18 4. Netzwerk- und Gremienarbeit 18 4.1. Regionale und überregionale Netzwerkarbeit 18 4.2. Team- und Leitungsberatungen 18 5. Supervision und Fortbildung 19 5.1. Supervision und Fallbesprechung 19 5.2. Fortbildung 19 6. Öffentlichkeitsarbeit 20 7. Schlussbemerkungen 21 Anhang: Beratungsstellenschild Seite: 2 Caritasverband für das Bistum Erfurt e.V. Caritasverband 1. Allgemeine Angaben 1.1. Name und Anschrift des Trägers Caritasverband für das Bistum Erfurt e.V. Wilhelm-Külz-Str. 33 99084 Erfurt Telefon: 0361 6729-0 Telefax: 0361 6729-122 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: www.dicverfurt.caritas.de 1.2. -

Mfs-Handbuch —

Anatomie der Staatssicherheit Geschichte, Struktur und Methoden — MfS-Handbuch — Bitte zitieren Sie diese Online-Publikation wie folgt: Monika Tantzscher: Hauptabteilung VI: Grenzkontrollen, Reise- und Touristenverkehr (MfS-Handbuch). Hg. BStU. Berlin 2005. http://www.nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0292-97839421300731 Mehr Informationen zur Nutzung von URNs erhalten Sie unter http://www.persistent-identifier.de/ einem Portal der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek. Vorbemerkung Mit dem Sturz der SED-Diktatur forderte die Demokratiebewegung in der ehemaligen DDR 1989/90 auch die Öffnung der Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes. Das Stasi- Unterlagen-Gesetz (StUG), am 20. Dezember 1991 mit breiter Mehrheit vom Parlament des vereinten Deutschlands verabschiedet, schaffte dafür die Grundlage. Zu den Aufgaben des Bundesbeauftragten für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik gehört die »Aufarbeitung der Tätig- keit des Staatssicherheitsdienstes durch Unterrichtung der Öffentlichkeit über Struktur, Methoden und Wirkungsweise des Staatssicherheitsdienstes« (§ 37 StUG). Dazu trägt dieses Kompendium »Anatomie der Staatssicherheit« bei. Das vorliegende Handbuch lie- fert die grundlegenden Informationen zu Geschichte und Struktur des wichtigsten Macht- instruments der SED. Seit 1993 einer der Schwerpunkte der Tätigkeit der Abteilung Bildung und Forschung, gelangen die abgeschlossenen Partien des MfS-Handbuches ab Herbst 1995 als Teilliefe- rungen zur Veröffentlichung. Damit wird dem aktuellen Bedarf -

Was War Die Stasi?

WAS WAR DIE STASI? EINBLICKE IN DAS MINISTERIUM FÜR STAATSSICHERHEIT DER DDR KARSTEN DÜMMEL | MELANIE PIEPENSCHNEIDER (HRSG.) 5., ÜBERARB. AUFLAGE 2014 ISBN 978-3-95721-066-1 www.kas.de INHALT 7 | VORWORT Melanie Piepenschneider | Karsten Dümmel 11 | „SCHILD UND SCHWERT DER SED” – WAS WAR DIE STASI? Karsten Dümmel 15 | EROBERUNG UND KONSOLIDIERUNG DER MACHT – ZWEI PHASEN IN DER GESCHICHTE DER STASI Siegfried Reiprich 22 | ÜBERWACHUNG Karsten Dümmel 26 | STRAFEN OHNE STRAFRECHT – FORMEN NICHT-STRAFRECHTLICHER VERFOLGUNG IN DER DDR Hubertus Knabe 28 | ZERSETZUNGSMASSNAHMEN Hubertus Knabe 35 | AUSREISEPRAXIS VON STASI UND MINISTERIUM DES INNERN Karsten Dümmel 39 | STASI UND FREIKAUF Karsten Dümmel 44 | GEPLANTE ISOLIERUNGSLAGER DER STASI Thomas Auerbach 5., überarb. Auflage (nach der 4. überarb. und erweiterten Auflage) 50 | BEISPIEL: DER OPERATIVE VORGANG VERRÄTER Wolfgang Templin Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne Zustimmung der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. 64 | STASI VON INNEN – DIE MITARBEITER unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Wolfgang Templin Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. 69 | HAUPTAMTLICHE MITARBEITER Jens Gieseke © 2014, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin 76| INOFFIZIELLE MITARBEITER Helmut Müller-Enbergs Gestaltung: SWITSCH Kommunikationsdesign, Köln. Druck: Bonifatius GmbH, Paderborn. 80| GESELLSCHAFTLICHE MITARBEITER FÜR SICHERHEIT Printed in Germany. Helmut Müller-Enbergs -

Otto-Von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg

Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg Fakultät für Geistes-, Sozial- und Erziehungswissenschaften Institut für Soziologie Georg Köhler Zur Tätigkeit der K I Ein soziologischer Rekonstruktionsversuch zur Rolle und Stellung der Arbeitsrichtung I der Kriminalpolizei der DDR A r b e i t s b e r i c h t Nr. 6 Internet-Fassung Mai, Jahr ISSN-1615-8229 Zur Reihe der Arbeitsberichte Die „Arbeitsberichte“ des Instituts für Soziologie versammeln theoretische und empirische Beiträge, die im Rahmen von Forschungsprojekten und Qualifikationsvorhaben entstanden sind. Präsentiert werden Überlegungen sowohl zu einschlägigen soziologischen Bereichen als auch aus angrenzenden Fachgebieten. Die Reihe verfolgt drei Absichten: Erstens soll die Möglichkeit der unverzüglichen Vorabveröffentlichung von theoretischen Beiträgen, empirischen Forschungsarbeiten, Reviews und Überblicksarbeiten geschaffen werden, die für eine Publikation in Zeitschriften oder Herausgeberzwecken gedacht sind, dort aber erst mit zeitlicher Verzögerung erscheinen können. Zweitens soll ein Informations- und Diskussionsforum für jene Arbeiten geschaffen werden, die sich für eine Publikation in einer Zeitschrift oder Edition weniger eignen, z. B. Forschungsberichte und –dokumentationen, Thesen- und Diskussionspapiere sowie hochwertige Arbeiten von Studierenden, die in forschungsorientierten Vertiefungen oder im Rahmen von Beobachtungs- und Empiriepraktika entstanden. Drittens soll diese Reihe die Vielfältigkeit der Arbeit am Institut für Soziologie dokumentieren. Impressum: Magdeburg: Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Herausgeber: Die Lehrstühle für Soziologie der Fakultät für Geistes-, Sozial- und Erziehungswissenschaften an der Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg Anschrift: Institut für Soziologie der Otto-von-Guericke-Universität Magdeburg „Arbeitsberichte des Instituts“ Postfach 41 20 39016 Magdeburg Sämtliche Rechte verbleiben bei den Autoren und Autorinnen. Auflage: 150 Redaktion: Prof. Dr. Barbara Dippelhofer-Stiem Prof. Dr. Heiko Schrader Gedruckte Fassungen sind erhältlich im Institut für Soziologie. -

Behind the Berlin Wall.Pdf

BEHIND THE BERLIN WALL This page intentionally left blank Behind the Berlin Wall East Germany and the Frontiers of Power PATRICK MAJOR 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York Patrick Major 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Major, Patrick. -

Die “Bahnpolizei” Der DDR 1949–1989

Jana Birthelmer: Die „Bahnpolizei“ der DDR 1949-1989 27 Die “Bahnpolizei” der DDR 1949–1989 Strukturen und Aufgaben der Transportpolizei am Beispiel des Grenzbezirks Magdeburg Jana Birthelmer Für die Reisenden, die in der DDR mit dem Zug unterwegs waren, gehörten sie zum alltäglichen Bild: die Polizisten der “Trapo”, der Transportpolizei, zuständig für die Si- cherheit und Ordnung in den Zügen und auf den Bahnhöfen der Deutschen Reichsbahn. Im Volksmund als “Bahnpolizei” bezeichnet, fielen die Mitarbeiter dieses Dienstzwei- ges der Deutschen Volkspolizei in ihren blauen Uniformen häufig durch forsches und wenig fahrgastfreundliches Verhalten auf. In der historischen Forschung wurde die “Trapo” bisher eher stiefmütterlich behandelt1. Dabei ermöglicht die Untersuchung ih- rer Tätigkeit jedoch einen interessanten Zugang zum Alltag des Reise- und Fortbewe- gungsnetzes der DDR, ebenso wie in die Kontrolle eines Raums, in dem nicht nur DDR- Bürger aufeinander trafen, sondern den auch westdeutsche Reisende betraten: den Zug. Der Blick auf die Arbeit der Transportpolizisten macht deutlich, daß diese in ihrem All- tag nicht nur normale polizeiliche Aufgaben hatten, sondern auch Teil des Überwa- chungs- und Repressionsapparates der DDR waren. Dies läßt sich exemplarisch in be- sonderem Maße am Grenzbezirk Magdeburg nachverfolgen. So desolat sich die Lage in der Forschung zur Transportpolizei darstellt, so erweist sich die Quellenlage im Gegensatz dazu als hervorragend und sehr ergiebig. Außer dem na- hezu vollständig erhaltenen Bestand der Deutschen Volkspolizei und der Transportpo- lizei des Bezirks Magdeburg für die 1950er und 1960er sowie zahlreicher bisher noch nicht aufbereiteter Akten der 1980er Jahre, stehen auch Bestände des MfS zur Verfü- gung, insbesondere der Hauptabteilungen IX, VI und XIX. -

Vertiefung Zum Plakat "Urlaub Und Erholung"

Urlaub und Erholung Vertiefung Inhalt Einführung 1. Dokumente zu einschränkenden Bestimmungen • Definitionen im Wörterbuch der Staatssicherheit, 1985 • Die staatliche Regulierung des Reiseverkehrs 2. Dokumente der Stasi über angebliche Fluchtversuche • Informationsbedarf zu einem Ermittlungsverfahren, 27.8.1985 • Verhalten eines Zivilbeschäftigten der Armee im Ausland, 4.10.1984 2 „Stasi. Was war das?“ | Urlaub und Erholung | Vertiefung Einführung zum Tourismus der Einwohner der DDR Die Organisation von Reisen für Einwohner der DDR übernahmen hauptsächlich die staatlichen Betriebe und die Gewerkschaft. Wer nicht in deren Massenunterkünfte wollte, nutzte die staatlichen Campingplätze, Jugendherbergen, Wanderquartiere oder private Kontakte. Für Jugendliche gab es seit 1975 das Jugendreisebüro der Freien Deutschen Jugend (FDJ), für Kinder rund 100 „Pionierlager“ und an die 5.000 Betriebsferienlager. Der Aufenthalt in diesen Ferienla- gern war extrem günstig und kostete rund 2-4 Mark pro Woche. Für Privatreisen in das sozialistische Ausland, etwa nach Bulgarien, galt mehrheitlich ein Genehmigungsverfahren. Innerdeutsche Reisen waren mit dem Bau der Mauer 1961 so gut wie unmöglich geworden: Ab 1964 durften zwar DDR- Rentner zunächst unter strengen Auflagen, ab 1969 etwas einfacher eine Reise in den Westen beantragen. Da allerdings nur 70 Mark der DDR ausgeführt werden durften, waren für sie in der Regel nur Besuche bei Verwandten möglich. Zur finanziellen Unterstützung führte die Bundesrepublik Deutschland daher 1970 ein so genanntes „Begrüßungsgeld“ in Höhe von 30 DM der Bundesrepublik Deutschland für DDR-Bürger ein, das zweimal im Jahr in Anspruch genommen werden konnte. Als die DDR ab 1. Juli 1988 die erlaubte Geldausfuhr von 70 auf 15 Mark kürzte, wurde das Begrüßungs- geld der Bundesrepublik auf 100 DM erhöht, jedoch auf eine einmalige Inanspruchnahme pro Jahr beschränkt. -

Lageberichte Der Deutschen Volkspolizei Im Herbst 1989 ------Eine Chronik Der Wende Im Bezirk Neubrandenburg

1 Die Lageberichte der Deutschen Volkspolizei im Herbst 1989 ----------------------------------------------- Eine Chronik der Wende im Bezirk Neubrandenburg Mit einem Anhang: Studie über das Verhältnis von Volkspolizei und Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, dargestellt am Beispiel des Kampfes gegen die mecklenburgische Landeskirche 1945 - 1989 2 Die Lageberichte der Deutschen Volkspolizei im Herbst 1989. Eine Chronik der Wende im Bezirk Neubrandenburg. Mit einem Anhang: Studie über das Verhältnis von Volkspolizei und Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, dargestellt am Beispiel des Kampfes gegen die mecklenburgische Landeskirche. Herausgeber: Die Landesbeauftragte für Mecklenburg-Vorpommern für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, Jägerweg 2, 19053 Schwerin Bearbeiter: Georg Herbstritt Druck der ersten Auflage (1998): Druckhaus Kersten Koepcke & Co., Güstrow 2., durchgesehene Auflage, Schwerin 2009 (nur online als pdf-Datei verfügbar) ISBN der gedruckten Auflage (1998): 3-933255-07-4 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Einführung ................................................................................................. 5 Dokumententeil: Die Lageberichte der Deutschen Volkspolizei im Herbst 1989 ................... 13 Anhang: Studie über das Verhältnis von Volkspolizei und Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, dargestellt am Beispiel des Kampfes gegen die mecklenburgische Landeskirche ......................................................... 235 Das politisch-operative Zusammenwirken - eine -

Polizei Chip 38

D ) 00 DpUT gT2D©g2g7 Chip 38 \ Polizei Nr.1/1991 Schwerpunkt: Polizeilicher Neubeginn in den Ländern der ehemaligen DDR außerdem: Neues Verfassungsschutzgesetz Todesschüsse 1990 Staatsschutz Bürgerrechte & Polizei CILIP Preis: 10,-- DM Herausgeber: Verein zur Förderung des Instituts für Bürgerrechte & öffentliche Sicherheit Verlag: Bürgerrechte & Polizei (CILIP), Malteser Str. 74-100, 1/46 Redaktion + Gestaltung: Otto Diederichs Satz: Marion Osterholz Übersetzungen: Dave Hanis Druck: Buch- und Offset-Druck, Lothar Braut Berlin, April 1991 Vertrieb: Kirschkern Buchversand, Hohenzollerndamm 199, 1000 Berlin 31 (Buchhandelsbestellungen an die Redaktion) Einzelpreis: 10,-- DM/Jahresabonnement (3 Hefte): 24,-- DM/ Institutionsabonnement: 45,-- DM ISSN 0932-5409 Alle Rechte bei den Autoren Zitiervorschlag: Bürgerrechte & Polizei (CILIP), Heft 38 (1/91) Bürgerrechte & Polizei 38 Redaktionelle Vorbemerkung 4 Vereinigte deutsche Sicherheit, Wolf-Dieter Narr 6 Das Polizeiaufgabengesetz der DDR, Heiner Busch 12 Stand des Polizeiaufbaus in den neuen Ländern, Otto Diederichs 17 Fragebögen und Personalkommissionen, Otto Diederichs 22 Gewerkschaftliche Probleme/Chancen infolge des Neu- aufbaus der Polizei in den neuen Ländern, Hermann Lutz 28 Ein grüner Polizeipräsident in Brandenburg?, Otto Diederichs 31 Das Gemeinsame Landeskriminalamt der fünf neuen Länder, Bernhard Gill 34 Bundesgrenzschutz im Aufwind, Falco Werkentin 40 Das Spezialeinsatzkommando Brandenburg, Wolfgang Gast 47 Datenchaos im "Wilden Osten", Lena Schraut 49 Das polizeiliche Meldewesen in der DDR, Kirsten Paritong-Waldheim u.a 56 Staatsschutz - Plädoyer für die Auflösung, Thilo Weichert 61 Tödlicher Schußwaffeneinsatz 1990 71 Geheimdienstgesetze, Heiner Busch 75 Bundesverfassungsschutzgesetz - BVerfSchG (Dokumentation) 88 Chronologie, Kea Tielemann 95 Literatur 101 Summaries 109 3 Bürgerrechte & Polizei 38 Redaktionelle Vorbemerkung von Otto Diederichs Die in der vorigen Ausgabe angekündigten Veränderungen bei Bürgerrechte & Polizei/CILIP sind mit dem vorliegenden Heft umgesetzt. -

Das Große Buch Der Transportpolizei Geschichten – Aufgaben – Uniformen Das Große Buch Der TRANSPORTPOLIZEI Das Große – Uniformen – Aufgaben Geschichten

Dieter Schulze Dieter Schulze Das große Buch der TRANSPORT- Schulze Dieter TRAPO POLIZEI Geschichten – Aufgaben – Uniformen Die Transportpolizei, kurz Trapo genannt, sorgte zwischen 1945 und 1990 in Ostdeutschland für Ordnung und Sicherheit auf dem Gelände der Deutschen Reichsbahn. Sie überwachte und kontrollierte das Schienennetz, die Bahnanlagen und Bahnhöfe, fungierte als Transport- begleiter, sicherte den Transitverkehr ab. Was vielen nicht bekannt ist: Sie war in der Tat eine Polizei innerhalb der Polizei – mit allen Gliederungen und Formationen. Erstmals gibt es eine fundierte, reich bebilderte Dokumentation über die Geschichte und TRANSPORTPOLIZEI Arbeit dieser besonderen, in der Historie einzigartigen Institution. Das große Buch der Transportpolizei Geschichten – Aufgaben – Uniformen Das große Buch der Das große – Uniformen – Aufgaben Geschichten edition berolina ISBN 978-3-95841-045-9 [D] 14,99 € [A] 15,50 € Dieter Schulze TRAPO Das große Buch der Transportpolizei Dieter Schulze, Jahrgang 1945, Diplom-Volkswirt, war von 1970 bis 2006 als Krimi- nalist tätig, u. a. als Leiter des Kommissariats Kriminaltechnik. Er gab sein kriminalis- tisches Wissen als Dozent für Kriminalistik und Kriminologie an der Hochschule der Sächsischen Polizei und von 2007 bis 2013 als Lehrbeauftragter an der Rechtswissen- schaftlichen Fakultät der Friedrich-Schiller-Universität in Jena im Fach »Kriminalistik für Juristen« weiter. Schulze ist Verfasser mehrerer Fachbuchreihen und Sachbücher, u. a. Das große Buch der Deutschen Volkspolizei. Geschichten – Aufgaben – Uniformen (edition berolina, 2016). Dieter Schulze TRAPO Das große Buch der Transportpolizei Geschichten Aufgaben Uniformen edition berolina 3 ISBN 978-3-95841-045-9 1. Auflage Alexanderstraße 1 10178 Berlin Tel. 01805/30 99 99 FAX 01805/35 35 42 (0,14 €/Min., Mobil max. -

Bstu / Abkürzungsverzeichnis

Abkürzungsverzeichnis Häufig verwendete Abkürzungen und Begriffe des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit Zusammengestellt und bearbeitet: Ralf Blum Rainer Eiselt (verantwortlicher Redakteur) Frank Joestel Klaus Richter (Leiter) Stephan Wolf Hans-Jürgen Zeidler Ein Gesamtverzeichnis und weitere lieferbare Publikationen erhalten Sie beim Bundesbeauftragten für die Un- terlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik, Abteilung Kommu- nikation und Wissen, 10106 Berlin E-Mail: [email protected] Tel.: 030 2324-8803 Fax: 030 2324-8809 Bestellungen und kostenlose Downloads vieler Publikationen auch unter: www.bstu.de Der Bundesbeauftragte für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen Deutschen Demokratischen Republik Abteilung Kommunikation und Wissen 10106 Berlin E-mail: [email protected] Abdruck und publizistische Nutzung sind nur mit Angabe des Verfassers und der Quelle sowie unter Beachtung der Bestimmungen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes gestattet. 12., geringfügig korrigierte Auflage Redaktion: Ralf Trinks Berlin 2020 ISBN 978-3-946572-47-3 Eine PDF-Version dieser Publikation ist unter der folgenden URN kostenlos abrufbar: urn:nbn:de: 0292-97839465724730 Inhalt Vorbemerkung zur 12. Auflage 5 Welche Abkürzungen wurden aufgenommen? 5 Zu den Anhängen 5 Hinweise für die Nutzung 6 1 Abkürzungen von A–Z 9 2 Anhänge 89 2.1 Römische Ziffern und Zahlen 90 2.2 Arabische Ziffern und Zahlen 94 2.3 Rechtsnormen mit Strafandrohungen 95 2.4 Allgemeine MfS-Vordrucke 106 2.5 Grundstrukturen des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit 110 2.5.1 MfS-Zentrale (1989) 110 2.5.2 Bezirksverwaltung (1989) 112 2.5.3 Kreisdienststelle (1989) 113 2.6 Erfassen, Registrieren, Speichern 114 2.6.1 Einleitung 114 2.6.2 Erfassungen und Registrierungen 114 2.6.3 Übersicht über die Entwicklung wesentlicher Erfassungen und Registrierungen des MfS 117 2.6.4 Informationsspeicher der Abteilung XII 122 2.6.5 Informationsspeicher der operativen Diensteinheiten 125 Literaturauswahl 129 Vorbemerkung zur 12. -

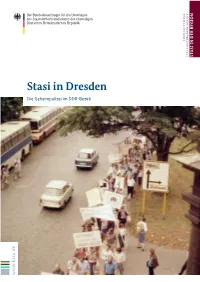

Stasi in Dresden. Die Geheimpolizei Im Ddr-Bezirk >> Einleitung 5

www.bstu.de Stasi in Dresden Stasi Die Geheimpolizei im DDR-Bezirk EINBLICKE IN DAS STASI-UNTERLAGEN-ARCHIV STASI IN DER REGION Peter Boeger, Elise Catrain (Hg.) Stasi in Dresden Die Geheimpolizei im DDR-Bezirk >> INHALTSVERZEICHNIS 3 Inhaltsverzeichnis Einleitung 4 »Stürzt die Regierung!« – der 17. Juni 1953 in Niesky 6 »Zutritt für Unbefugte verboten« – die Abschottung der Dresdner Stasi-Zentrale 12 Auf der Spur des Taxi-Agenten – Kalter Krieg in Kamenz 16 Augen und Ohren immer offen halten – das Spitzelnetz der Staatssicherheit 22 »Ich fordere die Umsiedlung!« – die Stasi bekämpft Ausreiseantragsteller 29 »Im Interesse und zum Schutz der Bürger«? – die Postkontrolle der Stasi 33 Staatsaffäre Opernpremiere – die Wiedereröffnung der Semper oper unter Stasi-Kontrolle 39 »Sportverräter« Kotte – die Stasi und der DDR-Fußball 43 Prag – Dresden – Hof: Sonderzüge in die Freiheit 49 Anmerkungen 56 Übersichten und Verzeichnisse 58 Die Dienststellen der Stasi im Bezirk Dresden 58 Struktur und Aufgaben der Stasi in Dresden 60 Kurzbiografien der Minister und der Leiter der Bezirksverwaltung Dresden 61 Abkürzungsverzeichnis 64 > Abbildung auf der Titelseite Stasi-Aktion ›Palme 87‹: Die Geheimpolizei beobachtet Teilnehmer am offiziell genehmigten Olof-Palme-Friedensmarsch auf dem Georgi- Dimitroff-Platz in Dresden (heute Schlossplatz). 1986 wird der schwedische Ministerpräsident Olof Palme, ein scharfer Kritiker des atomaren Wettrüstens, ermordet. Im September 1987 findet über mehrere Tage der Friedensmarsch durch die DDR statt, an dem auch politische ›Gegner‹ der SED teilnehmen. 18.9.1987 BStU, MfS, BV Dresden, AKG, Nr. 7634, Fo, Bl. 4 – Mitte 4 STASI IN DRESDEN. DIE GEHEIMPOLIZEI IM DDR-BEZIRK >> EINLEITUNG 5 > Der Zugang zu den Akten war eine zentrale Forderung der Demons tranten.