Nyira Near the Congo River, 1760 the Mikoni Crept

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NJE and SSH Client Suite

Sine Nomine Associates SSH Client Suite for CMS & NJE for Open Systems Neale Ferguson © 2019 Sine Nomine Associates Sine Nomine Associates CMS SSH Client Suite § Suite of tools: – Secure Copy: PSCP – Secure FTP: PSFTP – Secure Shell: PTERM § Modeled on Putty command line tools § Key generation § Uses public/private key pairs to eliminate the need for passwords § Compatible with modern OpenSSH releases § Not TLS 1.3 yet © 2007 SNA Sine Nomine Associates CMS SSH Client Suite § Supports: – Accessed SFS or minidisks – SFS specifications – Codepage translation © 2007 SNA Sine Nomine Associates PSCP § PSCP is a CMS implementation of the popular scp command available in many other environments. It provides a command-line client for encrypted file transfer between hosts originating from CMS to other machines pscp filea.text.a green.example.com:/u/walters/filea.text © 2007 SNA Sine Nomine Associates PSFTP § PSFTP is an interactive text-based client for the SSH-based SFTP (secure file transfer) protocol. It resembles the classic text-mode FTP client, with additional commands to handle the EBCDIC environment psftp –i private.ppk [email protected] © 2007 SNA Sine Nomine Associates PTERM § PTERM is a line-mode terminal emulator for the CMS SSH package. It provides a way to interact with a terminal session over an encrypted channel. PTERM operates only in line mode; it does not provide 3270 or VT100 emulation. It may be used to run a remote command or start an interactive session pterm [email protected] sh -c 'mycommand < inputfile' © 2007 SNA Sine Nomine Associates PUTTYGEN § PUTTYGEN is a tool to generate and manipulate SSH public and private key pairs. -

Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit Carried Our the Most Intensive Archaeological Investigation Yet Undertaken of Part of the East Midlands Countryside

THE MJ[Ll'O N KJE '1{NJE S PROJJE C 1' R. J. ZEEPVAT Between 1971 and 1991, the Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit carried our the most intensive archaeological investigation yet undertaken of part of the East Midlands countryside. This paper summarises the arch.aeo!Ggicallandscapes that can be constructed ji·om the results of this work, and assesses the methods employed to obtain them. Introduction Milton Keynes is underlain by beds of Oxford The new city of Milton Keynes covers an area Clay, which outcrop extensively on the west of some ninety square kilometres, straddling side of the Ouzel floodplain, which forms the the narrowest part of north Buckinghamshire, east side of the city. Much of this central area is with the counties of Bedfordshire and North• covered by glacial deposits of Boulder Clay, amptonshire to the south-east and north res• whilst both glacial and alluvial deposits of pectively (Fig. 1). Part of the reasoning behind gravel are found in the Ouse and Ouzel valleys. the choice of this location can be seen in its Rocky outcrops are mainly confined to areas situation on the principal natural 'corridor' bordering the O use valley. Soils in the area are linking the south-east to the Midlands and heavy, though lighter soils are found in areas of north, a route followed by all the major forms gravel subsoil, and drainage is generally poor of surface transport, ancient and modern. even in the riv·er valleys, which were prone to flooding until recent years. Until the designation of Milton Keynes, the area was devoted almost entirely to agri• Despite its situation on a major communica• culture. -

Bez Bjed Nost I Si Gur Nost Na Pr Vom Mje Stu!

INTERVJU Ivan Bra jo vić, mi ni star sa o bra ća ja i po mor stva u Vla di Re pu bli ke Cr ne Go re Bez bjed nost i si gur nost na pr vom mje stu! PUT Plus: Ka ko oce nju je te ak tu el no Sve ze mlje re gi o na: Hr vat ska, Sr bi ja, sta nje u put noj pri vre di Cr ne Go re, kao Al ba ni ja, Ko so vo i dr, po sljed njih go di Ivan Bra jo vić, ro đen 1962. go di ne i osta lih ze ma lja s ko ji ma je Cr na Go ra u na vi še ula žu u una pr je đe nje sa o bra ćaj u Pod go ri ci, osnov nu i sred nju ško lu su sed skim od no si ma? ne in fra struk tu re, ali i raz voj de fi ni sa nih za vr šio je u Da ni lov gra du, a Gra đe vin tran sport nih ko ri do ra. Na rav no, ukup na ski fa kul tet, sa o bra ćaj ni smer (pro gla Ivan Bra jo vić: Po li tič ke, ge o graf ske ocje na bi bi la da se sta nje umno go me šen za naj bo ljeg stu den ta Gra đe vin i eko nom ske pro mje ne ko je su se de si le po pra vi lo, ali da je pred na ma još puno skog fa kul te ta), za vr šio je u Pod go ri ci. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

Evrop Ska Po Ve Lja O Lo Kal Noj Sa Mo U Pra Vi Kao in Stru Ment Za De Fi Ni Sa Nje I Za Šti Tu Prin Ci Pa Lo Kal Ne Sa Mo U Pra Ve

Dr Ve sna Alek sić* UDK: 061.1:352 Dr Mi lan Po ču ča** BIBLID: 0352-37.13(2008)25,101-106 EVROP SKA PO VE LJA O LO KAL NOJ SA MO U PRA VI KAO IN STRU MENT ZA DE FI NI SA NJE I ZA ŠTI TU PRIN CI PA LO KAL NE SA MO U PRA VE RE ZI ME: De cen tra li za ci ja fi skal nog si ste ma jed ne dr ža ve zah te va pru ža nje od go- vo ra na vi še pi ta nja. Naj zna čaj ni je pi ta nje, sva ka ko, je ras po de la jav nih ras ho da, jer se fi nan si ra nje od re đu je pre ma po tre ba ma. Ta ko đe, ne ma nje va žno pi ta nje je i ras po de la jav nih pri ho da. Zna čaj no je na ve sti ka ko u raz li či tim dr ža va ma de lu - ju raz li či ti fak to ri ko ji uti ču na stva ra nje dru štve no-po li tič kog i eko nom skog si - ste ma, a ta ko đe i na stva ra nje fi skal nog si ste ma. Evrop ska Po ve lja o lo kal noj sa- mo u pra vi pred sta vlja in stru ment za de fi ni sa nje i za šti tu prin ci pa lo kal ne auto no - mi je, i pred sta vlja je dan od stu bo va de mo kr a ti je ko ju Ve će Evro pe bra ni i raz vi ja kao te melj nu evrop sku vred nost. -

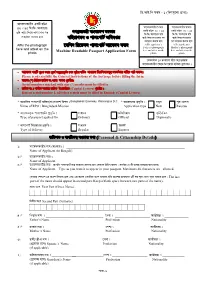

MRP Application Form

¢X.BC.¢f glj - 1 (¢he¡j¨−mÉ fÊ¡fÉ) A¡−hceL¡l£l HL¢V l¢Pe 55 ^ 45 ¢jx¢jx A¡L¡−ll A¡−hceL¡l£l ¢fa¡l A¡−hceL¡l£l j¡a¡l NZfÊS¡a¿»£ h¡wm¡−cn plL¡l HL¢V l¢Pe 30 ^ 25 HL¢V l¢Pe 30 ^ 25 R¢h A¡W¡ ¢c−u m¡N¡−e¡l fl ¢jx¢jx A¡L¡−ll R¢h ¢jx¢jx A¡L¡−ll R¢h paÉ¡ue Ll−a q−h h¢ql¡Nje J f¡p−f¡VÑ A¢dcçl A¡W¡ ¢c−u m¡N¡−e¡l fl A¡W¡ ¢c−u m¡N¡−e¡l paÉ¡ue Ll−a q−h fl paÉ¡ue Ll−a q−h Affix the photograph Affix applicant’s Affix applicant’s −j¢ne ¢l−Xhm f¡p−f¡VÑ A¡−hce glj Father’s photograph Mother’s photograph here and attest on the Machine Readable Passport Application Form here and attest on the here and attest on the photo photo photo −Lhmj¡œ 15 hvp−ll e£−Q AfË¡çhuú A¡−hceL¡l£l −r−œ Ef−l¡š² R¢hàu fË−u¡Se z • A¡−hce fœ¢V f¨lZ Ll¡l f¨−hÑ Ae¤NÊqf§hÑL −no fªù¡u h¢ZÑa p¡d¡le ¢e−cÑne¡pj§q paLÑa¡l p¢qa f¡W Ll²ez Please read carefully the General Instructions at the last page before filling the form. • a¡lL¡ (*) ¢Q¢q²a œ²¢jL ew …−m¡ AhnÉ f¨lZ£uz Serial numbers marked with star (*) marks must be filled in. -

Multilingualism, the Needs of the Institutions of the European Community

COMMISSION Bruxelles le, 30 juillet 1992 DES COMMUNAUTÉS VERSION 4 EUROPÉENNES SERVICE DE TRADUCTION Informatique SdT-02 (92) D/466 M U L T I L I N G U A L I S M The needs of the Institutions of the European Community Adresse provisoire: rue de la Loi 200 - B-1049 Bruxelles, BELGIQUE Téléphone: ligne directe 295.00.94; standard 299.11.11; Telex: COMEU B21877 - Adresse télégraphique COMEUR Bruxelles - Télécopieur 295.89.33 Author: P. Alevantis, Revisor: Dorothy Senez, Document: D:\ALE\DOC\MUL9206.wp, Produced with WORDPERFECT for WINDOWS v. 5.1 Multilingualism V.4 - page 2 this page is left blanc Multilingualism V.4 - page 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 0. INTRODUCTION 1. LANGUAGES 2. CHARACTER RÉPERTOIRE 3. ORDERING 4. CODING 5. KEYBOARDS ANNEXES 0. DEFINITIONS 1. LANGUAGES 2. CHARACTER RÉPERTOIRE 3. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION CONCERNING ORDERING 4. LIST OF KEYBOARDS REFERENCES Multilingualism V.4 - page 4 this page is left blanc Multilingualism V.4 - page 5 0. INTRODUCTION The Institutions of the European Community produce documents in all 9 official languages of the Community (French, English, German, Italian, Dutch, Danish, Greek, Spanish and Portuguese). The need to handle all these languages at the same time is a political obligation which stems from the Treaties and cannot be questionned. The creation of the European Economic Space which links the European Economic Community with the countries of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) together with the continuing improvement in collaboration with the countries of Central and Eastern Europe oblige the European Institutions to plan for the regular production of documents in European languages other than the 9 official ones on a medium-term basis (i.e. -

Cyrillic # Version Number

############################################################### # # TLD: xn--j1aef # Script: Cyrillic # Version Number: 1.0 # Effective Date: July 1st, 2011 # Registry: Verisign, Inc. # Address: 12061 Bluemont Way, Reston VA 20190, USA # Telephone: +1 (703) 925-6999 # Email: [email protected] # URL: http://www.verisigninc.com # ############################################################### ############################################################### # # Codepoints allowed from the Cyrillic script. # ############################################################### U+0430 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER A U+0431 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER BE U+0432 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER VE U+0433 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER GE U+0434 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER DE U+0435 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER IE U+0436 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZHE U+0437 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ZE U+0438 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER II U+0439 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHORT II U+043A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KA U+043B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EL U+043C # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EM U+043D # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EN U+043E # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER O U+043F # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER PE U+0440 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ER U+0441 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER ES U+0442 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TE U+0443 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER U U+0444 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER EF U+0445 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER KHA U+0446 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER TSE U+0447 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER CHE U+0448 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHA U+0449 # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER SHCHA U+044A # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER HARD SIGN U+044B # CYRILLIC SMALL LETTER YERI U+044C # CYRILLIC -

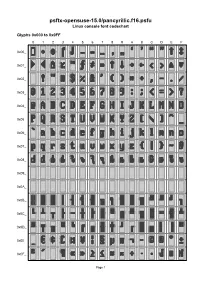

Psftx-Opensuse-15.0/Pancyrillic.F16.Psfu Linux Console Font Codechart

psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.psfu Linux console font codechart Glyphs 0x000 to 0x0FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x00_ 0x01_ 0x02_ 0x03_ 0x04_ 0x05_ 0x06_ 0x07_ 0x08_ 0x09_ 0x0A_ 0x0B_ 0x0C_ 0x0D_ 0x0E_ 0x0F_ Page 1 Glyphs 0x100 to 0x1FF 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 A B C D E F 0x10_ 0x11_ 0x12_ 0x13_ 0x14_ 0x15_ 0x16_ 0x17_ 0x18_ 0x19_ 0x1A_ 0x1B_ 0x1C_ 0x1D_ 0x1E_ 0x1F_ Page 2 Font information 0x017 U+221E INFINITY Filename: psftx-opensuse-15.0/pancyrillic.f16.p 0x018 U+2191 UPWARDS ARROW sfu PSF version: 1 0x019 U+2193 DOWNWARDS ARROW Glyph size: 8 × 16 pixels 0x01A U+2192 RIGHTWARDS ARROW Glyph count: 512 Unicode font: Yes (mapping table present) 0x01B U+2190 LEFTWARDS ARROW 0x01C U+2039 SINGLE LEFT-POINTING Unicode mappings ANGLE QUOTATION MARK 0x000 U+FFFD REPLACEMENT 0x01D U+2040 CHARACTER TIE CHARACTER 0x01E U+25B2 BLACK UP-POINTING 0x001 U+2022 BULLET TRIANGLE 0x002 U+25C6 BLACK DIAMOND, 0x01F U+25BC BLACK DOWN-POINTING U+2666 BLACK DIAMOND SUIT TRIANGLE 0x003 U+2320 TOP HALF INTEGRAL 0x020 U+0020 SPACE 0x004 U+2321 BOTTOM HALF INTEGRAL 0x021 U+0021 EXCLAMATION MARK 0x005 U+2013 EN DASH 0x022 U+0022 QUOTATION MARK 0x006 U+2014 EM DASH 0x023 U+0023 NUMBER SIGN 0x007 U+2026 HORIZONTAL ELLIPSIS 0x024 U+0024 DOLLAR SIGN 0x008 U+201A SINGLE LOW-9 QUOTATION 0x025 U+0025 PERCENT SIGN MARK 0x026 U+0026 AMPERSAND 0x009 U+201E DOUBLE LOW-9 QUOTATION MARK 0x027 U+0027 APOSTROPHE 0x00A U+2018 LEFT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x028 U+0028 LEFT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x00B U+2019 RIGHT SINGLE QUOTATION 0x029 U+0029 RIGHT PARENTHESIS MARK 0x02A U+002A ASTERISK -

Dentofacial Changes After Treatment with Prefabricated Functional Appliance T4CII

CASE REPORT / PRIKAZ IZ PRAKSE Serbian Dental Journal, vol. 60, No 2, 2013 93 UDC: 616.314.25/.26-085 DOI: 10.2298/SGS1302093A Dentofacial Changes after Treatment with Prefabricated Functional Appliance T4CII Ema Aleksić1, Maja Lalić2, Jasmina Milić1, Mihajlo Gajić2, Zdenka Stojanović3 1Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Stomatology Pančevo, University Business Academy Novi Sad, Pančevo, Serbia; 2Department of Paediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Stomatology Pančevo, University Business Academy Novi Sad, Pančevo, Serbia; 3Clinic of Dentistry, Military Medical Academy, Belgrade, Serbia SUMMARY Introduction Functional maxillary orthodontics has a large number of different mobile devices with different effects on craniomandibular system and great capabilities in solving many orthodontic problems. The aim of this article was to show the effects of 9-month treatment of malocclusion class II, division 1 in a 14-year-old female patient using pre- fabricated functional appliance Trainer T4CII. Case Outline Skeletal distal relation, deep bite, increased overjet, narrowness and irregular position of upper and lower frontal teeth are indicated for orthodontic treatment with fixed appliance. After refusal of fixed appliance therapy, a female patient was proposed treatment with mobile orthodontic appliance. A pre-fabricated functional appliance Trainer T4CII was delivered to the patient. She was motivated and she was wearing appliance at night and 2-3 hours during the day. After 9 months of treatment there was a significant improvement in the position of upper and lower frontal teeth and reshaping of upper and lower dental arch, yet overbite and overjet were corrected. Conclusion Surprisingly good and fast improvement of all problems within class II, division 1 in a 14-year-old patient was achieved with prefabricated functional appliance Trainer T4CII. -

The Scorecyr Cyrillic Font for Use in Score Date: January 18, 2004 Version: 1.01 Author: Jan De Kloe

1 Title: The ScoreCyr Cyrillic font for use in Score Date: January 18, 2004 Version: 1.01 Author: Jan de Kloe Introduction The font ScoreCyr was assembled from an existing industry font and adapted for use in Score by Matanya Ophee. This is a description of the font’s characters and how to use them. Use of the font is based on a Standard Russian keyboard which has different layout than a Latin keyboard. To use the font conveniently you either need a Russian keyboard1 or use SipText with the Cyrillic extension. Without a Russian keyboard, working with this font is cumbersome but not impossible, and this document is a help. The SipText program shows a Russian Keyboard on the screen and it can be used as a layout help, or keys can be pushed with the mouse. In this document, Cyrillic characters are shown in Arial Bold to distinguish the script from Latin characters. The font How to use the font There is no phonetic or visual correspondence between Latin and Cyrillic keyboards. On top of that, Score does not show the Cyrillic graphic representation of text and it is not until printing that the user sees the result of Cyrillic text editing. Also, there are some common characters like comma and period for which the font has no provision without adaptation of FONTINIT.PSC and the simplest alternative is to switch to a Latin font such as Times-Roman for those characters. Given here is the modern Russian alphabet. The transliteration is according to the “modified Library of Congress” standard. -

Smisao Održive Kulture

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory Culture and Sustainable Development at Times of Crisis 39 Jelena Đurić Institut za fi lozofi ju i društvenu teoriju, Univerzitet u Beogradu, Beograd SMISAO ODRŽIVE KULTURE Shva ta nje1 smi sla odr ži ve kul tu re iz i sku je is tra ži va nje zna če nja ovog iz- ra za ko ja pro is ti ču iz nje go vih raz li či tih upo tre ba. Ovaj iz raz po či va na poj- mu odr ži vo sti ko ji se od no si na sva ki kul tur ni obra zac ko ji mo že iz nu tra da se ob na vlja, da se sa mo ob na vlja. On zna či isto što i kul tu ra odr ži vo sti s ob zi rom da odr ži vost ima ključ ni zna čaj, ma da nje no zna če nje ni je pr ven stve no eko- nom ske pri ro de. Da kle, kul tu ra ni je nu žno odr ži va uko li ko ima moć sa mo fi - nan si ra nja – to zna če nje je za pra vo neo dr ži vo sa sta no vi šta kul tu re u naj ši rem smi slu re či, kul tu re ko ja tek tre ba da se us po sta vi i da se po ka že odr ži vom u uslo vi ma po sto je će eko nom ske, eko lo ške i so ci jal ne kri ze.