Downloaded From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inhoudsopgave

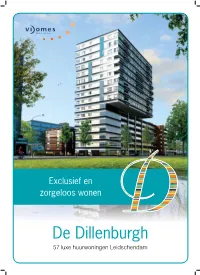

Inhoudsopgave 1. Leidschendam-Voorburg P 3 2. De Dillenburgh P 4 3. Wonen voor nu en in de toekomst P 6 4. Gebouwopzet P 8 5. Type woningen P 10 6. Uw woning in detail P 20 7. Verhuur informatie P 22 Bijlage: verhuurtekeningen 1. Leidschendam-Voorburg Leidschendam, sinds 2002 samengevoegd met de gemeente Voorburg, telt ongeveer 40.000 inwoners. Het voorzieningenniveau in de gemeente is hoog, zoals het grote winkelcentrum Leidsenhage, met veel grote en bekende winkels. Maar ook het historische oude winkelcentrum van Leidschendam. Ook zijn er verschillende sportgelegenheden, een zwembad en een bibliotheek. In de nabije omgeving zijn tal van recreatiemogelijkheden zoals, wandelen in natuurgebied de Horsten, zonnen en/of zwemmen in recreatiegebied Vlietland, een terrasje pakken bij het gezellige sluisje van Leidschendam. Ook kent de gemeente veel historische plekken zoals bijvoorbeeld de Molendriegang, gebouwd rond 1672. Er is een goede verbinding met openbaar vervoer; diverse bus- en tramverbindingen zijn op loopafstand gelegen. Met de auto bent u zo op de A4, A12 en A13. Leidschendam-Voorburg ligt zeer centraal in de de Randstad. Kortom, in Leidschendam-Voorburg is het heerlijk wonen. 3 Z Prins Frederiklaan . Voorzieningen zorg & welzijn maatschappelijke functie’s e.d. Entree Entree Binnentuin Prinsenhof Toren vrije sector woningen Bestaande bouw (renovatie) Lift Lift Johan Willem Frisolaan Voorbehoud bij situatietekening Dillenburgsingel De situatietekening is bedoeld om u een indruk te geven van de woonom- geving van De Dillenburg. Aan deze situatietekening kunnen geen rechten aan worden ontleend. De inrichting van de openbare ruimte (aanleg van wegen, groenvoorzieningen en parkeerplaatsen) is slechts een impressie. U dient er rekening mee te houden dat deze nog kunnen wijzigen. -

Quasi-Experimental Evidence on the Effect of Traffic Externalities on Housing Prices

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Ossokina, Ioulia; Verweij, Gerard Conference Paper Quasi-experimental evidence on the effect of traffic externalities on housing prices 51st Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "New Challenges for European Regions and Urban Areas in a Globalised World", 30 August - 3 September 2011, Barcelona, Spain Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: Ossokina, Ioulia; Verweij, Gerard (2011) : Quasi-experimental evidence on the effect of traffic externalities on housing prices, 51st Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "New Challenges for European Regions and Urban Areas in a Globalised World", 30 August - 3 September 2011, Barcelona, Spain, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/120072 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

Investeren in De Toekomst

Investeren in de toekomst 1 De kracht van Brookland Brookland is een Nederlands familiebedrijf dat zich Wij zoeken steeds naar een optimale combinatie bezighoudt met het ontwikkelen, kopen en verkopen van de drie W’s: wonen, winkelen en werken. van nieuwe winkelcentra en wooncomplexen. Dit bevordert niet alleen het woongemak, maar Wij verzorgen zowel het financieel, technisch en verbetert ook de leefbaarheid van winkelgebieden. commercieel beheer alsmede de verhuur van de Bovendien leggen wij ons in toenemende mate woningen en winkels in onze portefeuille. toe op toekomstbestendig bouwen met oog voor Bij Brookland geloven wij dat hoge kwaliteit, duurzaamheid en energiezuinigheid. persoonlijke service en een gunstige huur prima Wilt u woon- of winkelruimte huren bij Brookland samengaan. Onze complexen bevinden zich voor- of weet u een interessante locatie voor een nieuw- namelijk in de Randstad, grofweg het gebied tussen bouwproject? Wij horen het graag. Kijk voor nieuwe Zaandam, Utrecht, de Moerdijkbrug en de Noord- projecten en het laatste nieuws op www.brookland.nl. zee kust. Investeren Wonen, in de winkelen en toekomst werken 2 3 Woon- en winkelconcepten Brookland ontwikkelt en beheert woon- en winkelconcepten waarin men wonen, winkelen en werken kan combineren. Dit bevordert niet alleen het woongemak, maar ook de leefbaarheid van winkelgebieden. Meer dan 50 locaties Parkeren Wij beheren ruim 120.000 m2 aan winkelruimte Wij hechten veel waarde aan comfortabel winkelen verdeeld over meer dan 50 winkellocaties in de en wonen. Dit betekent dat wij ons inzetten voor Randstad. Dit varieert van een winkel met een voldoende parkeerruimte – variërend van 40 tot vloeroppervlakte van 80 m2 tot complete winkel- 300 parkeerplaatsen – voor het winkelend publiek. -

Reglement Van De Gezamenlijke Regionale Klachtencommissie Van

Reglement van de gezamenlijke Regionale Klachtencommissie van Stichting Radius Leiden en Oegstgeest Stichting Pluspunt Leiderdorp Voorschoten Voor Elkaar Welzijnskompas Hillegom Lisse Stichting De Spil Kaag en Braassem Welzijn Teylingen 2 Uitgave: Regionale Klachtencommissie Vormgeving/druk: Secretariaat Stichting Radius Leiden, juni 2018 Inhoud Blz. Inleiding 4 Klachtrechtreglement 5 Artikel 1 - Begripsomschrijvingen 5 Artikel 2 - Samenstelling klachtencommissie 5 Artikel 3 - Wraking en verschoning 6 Artikel 4 - Indiening van de klacht 6 Artikel 5 - Behandeling van de klacht 7 Artikel 6 - Bijstand 8 Artikel 7 - Het verstrekken van inlichtingen 8 Artikel 8 - Inzagerecht 8 Artikel 9 - Beslissing klachtencommissie 8 Artikel 10 - Maatregelen bestuur/directie 9 Artikel 11 - Periodieke rapportage 9 Artikel 12 - Verslag 9 Artikel 13 - Bekendmaking klachtenregeling 9 Artikel 14 - Geheimhouding 9 Artikel 15 - Beschikbaar stellen faciliteiten 9 Artikel 16 - Kosten procedure 10 Artikel 17 - Bekorten termijnen 10 Artikel 18 - Vaststelling en wijziging van dit reglement 10 Artikel 19 - Aansprakelijkheid Artikel 20 - Slotbepalingen 10 3 Inleiding. De wet. Op grond van de Wet klachtrecht (1-8-1995) dienen welzijnsorganisaties een regeling te treffen voor de behandeling van klachten over gedrag van medewerkers jegens een klant. Deze regeling voorziet erin dat dergelijke klachten van klanten worden behandeld door een klachtencommissie. De klachtencommissie dient haar werkzaamheden te verrichten volgens een door deze commissie op te stellen reglement. Voorts geeft de wet een aantal voorschriften met betrekking tot de samenstelling van deze commissie en met betrekking tot de te volgen procedure bij de behandeling van de klachten. Het doel van de wet is allereerst gericht op een versterking van de rechtspositie van de klant. Maar de wetgever gaat er ook van uit dat een goede klachtenbehandeling een bijdrage zal leveren aan de kwaliteit van de zorg- en dienstverlening. -

Klasse Indeling Veldvoetbal Seizoen: 2021-2022 District West 2

Klasse indeling Veldvoetbal Seizoen: 2021-2022 District West 2 Jeugd Onder 7 1e Klasse ASW JO7-1 HWD JO7-1 Zoetermeer JO7-1 BMT JO7-1 HWD JO7-2 Zoetermeer JO7-2 BMT JO7-2 Leidschenveen JO7-1 Zoetermeer JO7-3 BSC '68 JO7-1 Leidschenveen JO7-2 Zoetermeer JO7-4 BVCB JO7-1 Leidschenveen JO7-3 Zuid West JO7-1 BVCB JO7-2 Leidschenveen JO7-4 Zwaluwen JO7-1 Be Fair JO7-1 Maense JO7-1 Zwaluwen JO7-2 Blauw-Zwart JO7-1 NOCKralingen JO7-1 sv Poortugaal JO7-1 Blauw-Zwart JO7-2 ODB JO7-1 sv Poortugaal JO7-2 Bolnes JO7-1 Ommoord JO7-1 v.v. Hekelingen JO7-1 Botlek JO7-1 Quick Steps JO7-1 v.v. Hekelingen JO7-2 Buytenpark JO7-1 RCL JO7-1 CVC Reeuwijk JO7-1 RDM JO7-1 CVC Reeuwijk JO7-2 REMO JO7-1 CVC Reeuwijk JO7-3 Rhoon JO7-1 Charlois, sv JO7-1 Rhoon JO7-2 Charlois, sv JO7-2 Rijnm/Hgvl.Sp. JO7-1 DSVP JO7-1 Rijnm/Hgvl.Sp. JO7-2 DSVP JO7-2 Rijnvogels JO7-1 DSVP JO7-3 Rockanje JO7-1 DSVP JO7-4 Roodenburg JO7-1 DVC JO7-1 Roodenburg JO7-2 DVC JO7-2 SVC'08 JO7-1 DVC JO7-3 SVC'08 JO7-2 DoCoS JO7-1 SVC'08 JO7-3 Duindorp sv JO7-1 SVC'08 JO7-4 Duindorp sv JO7-2 SVH JO7-1 FC IJsselmonde JO7-1 Scheveningen JO7-1 FC Vlotbrug JO7-1 Siveo '60 JO7-1 FC Vlotbrug JO7-2 Sparta (AV) JO7-1 FCB/FC Banlieue JO7-1 Sparta (AV) JO7-2 FCB/FC Banlieue JO7-2 Sparta (AV) JO7-3 Floreant JO7-1 Sparta (AV) JO7-4 Floreant JO7-2 Sporting Leiden JO7-1 Forum Sport JO7-1 Sporting Leiden JO7-2 Forum Sport JO7-2 Sporting Leiden JO7-3 Forum Sport JO7-3 St.Hooger JO7-1 Forum Sport JO7-4 TAC'90 JO7-1 Forum Sport JO7-5 VCS JO7-1 Full Speed JO7-1 Voorschoten'97 JO7-1 Full Speed JO7-2 Voorschoten'97 -

Quantifiers and Selection : on the Distribution of Quantifying Expressions in French, Dutch and English Doetjes, J.S

Quantifiers and Selection : on the distribution of quantifying expressions in French, Dutch and English Doetjes, J.S. Citation Doetjes, J. S. (1997, November 27). Quantifiers and Selection : on the distribution of quantifying expressions in French, Dutch and English. Holland Academic Graphics, Leiden. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/19731 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/19731 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Quantifiers and Selection Quantifiers and Selection On the Distribution of Quantifying Expressions in French, Dutch and English Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Dr. W.A. Wagenaar, hoogleraar in de faculteit der Sociale Wetenschappen, volgens besluit van het College van Dekanen te verdedigen op donderdag 27 november 1997 te klokke 15.15 uur door J ENNY S ANDRA D OETJES geboren te Leidschendam in 1965 Promotiecommissie promotor: Prof. dr. J.G. Kooij co-promotor: Dr. T.A. Hoekstra referent: Prof. dr. J.E.C.V. Rooryck overige leden: Dr. H. de Hoop (Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht) Prof. dr. H.E. de Swart (Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht) CIP-GEGEVENS KONINKLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Doetjes, Jenny Sandra Quantifiers and Selection — On the Distribution of Quantifying Expressions in French, Dutch and English / Jenny Sandra Doetjes. — The Hague : Holland Academic Graphics. — (HIL dissertations ; 32) Proefschrift Rijksuniversiteit Leiden. — Met lit. opg. ISBN NUGI 941 Trefw.: syntaxis, semantiek, kwantificatie ISBN © 1997 by Jenny Doetjes. -

'We Zijn Kwetsbaar in Ons Eentje'

Interview Arno Korsten met De Volkskrant, 12 september 2014, p. 11. ‘We zijn kwetsbaar in ons eentje’ Bestuurlijke herindeling van gemeenten ligt gevoelig, maar achter de schermen krijgt samenwerking steeds vaker het karakter van een ambtelijke fusie Van onze verslaggever Bart Dirks VOORSCHOTEN/ DEN HAAG Jeroen Staatsen is burgemeester van de zelfstandige gemeente Voorschoten, maar zijn ambtenaren moet hij delen met burgemeester Jan Hoekema van Wassenaar. Per 1 januari 2013 zijn de twee gemeenten, elk met ongeveer 25.000 inwoners, ambtelijk gefuseerd. De ‘werkorganisatie Duivenvoorde’ staat in dienst van beide Zuid-Hollandse gemeenten. ‘We merkten dat we in ons eentje toch wat kwetsbaar werden’, zegt Staatsen. ‘Soms was een beleidsterrein een eenmanspost. Als de ambtenaar onderwijs ziek was, dan gingen de scholen bij wijze van spreken een week dicht.’ In 2012 besloten de buurgemeenten al samen te werken op terreinen als financiën, ict en personeelszaken. Sinds ruim anderhalf jaar zijn alle diensten geïntegreerd. Die ambtelijke fusie blijkt wel zo efficiënt. Hadden Voorschoten en Wassenaar hadden samen 400 formatieplaatsen, inmiddels is 10 procent van de ambtenaren wegbezuinigd. ‘Dat scheelt jaarlijks 2 à 3 miljoen euro’, rekent burgemeester Staatsen voor. ‘Daarnaast hebben we miljoenen en miljoenen bespaard op de inhuur van externe adviseurs. Dankzij onze gezamenlijke werkorganisatie hebben we van veel meer zaken verstand dan ieder voor zich.’ Variaties Vooral de laatste jaren gaat het hard met het aantal ambtelijke fusies, in tal van variaties. De Vereniging voor Nederlandse Gemeenten (VNG) telt uit de losse pols een stuk of dertig fusies waarbij tachtig gemeenten betrokken zijn. Uit een onderzoek in 2012 van het blad Binnenlands Bestuur bleek dat 81 procent van alle gemeenten nadenkt over vormen van gezamenlijke bedrijfsvoering. -

Indeling Van Nederland in 22 Grootstedelijke Agglomeraties En Stadsgewesten Gemeentelijke Indeling Van Nederland Op 1 Januari 2015

Indeling van Nederland in 22 grootstedelijke agglomeraties en stadsgewesten Gemeentelijke indeling van Nederland op 1 januari 2015 Legenda Gemeentegrens Stadsgewesten Grootstedelijke agglomeraties 0 5 10 15 20 Kilometers De namen van gemeenten met 100 000 of meer inwoners zijn kapitaal afgedrukt. Bij de gemeentegrenzen is geen rekening gehouden met het tot de gemeenten behorende buitenwater. Overzicht van de 22 stadsgewesten op 1 januari 2015 Overzicht van de 22 grootstedelijke agglomeraties op 1 januari 2015 01 Groningen 12 Leiden 01 Groningen 19 Eindhoven Bedum Katwijk Haren Eindhoven Ten Boer Leiden Groningen Geldrop-Mierlo Groningen Leiderdorp Son en Breugel Haren Noordwijk Veldhoven Leek Noordwijkerhout 02 Leeuwarden Waalre Marum Oegstgeest Noordenveld Teylingen Leeuwarden Tynaarlo Voorschoten 20 Geleen/Sittard Winsum Zoeterwoude Zuidhorn 03 Zwolle Beek Sittard-Geleen 13 ’s-Gravenhage Zwolle Stein 02 Leeuwarden Delft het Bildt 's-Gravenhage 04 Enschede 21 Heerlen Leeuwarden Leidschendam-Voorburg Leeuwarderadeel Midden-Delfland Enschede Brunssum Menameradiel Pijnacker-Nootdorp Heerlen Tytsjerksteradiel Rijswijk Kerkrade Wassenaar 05 Apeldoorn Landgraaf Westland 03 Zwolle Zoetermeer Apeldoorn 22 Maastricht Dalfsen Hattem 14 Rotterdam 06 Arnhem Maastricht Heerde Zwolle Albrandswaard Arnhem Barendrecht Rozendaal Brielle 04 Enschede Capelle aan den IJssel Hellevoetsluis 07 Nijmegen Borne Krimpen aan den IJssel Enschede Maassluis Nijmegen Hengelo Nissewaard Losser Ridderkerk Oldenzaal Rotterdam 08 Amersfoort Schiedam Vlaardingen Leusden 05 -

TNO-FEL Den Haag

TNO Fysisch en Elektronisch Laboratorium Routebeschrijving TNO-FEL Den Haag TNO-FEL Oude Waalsdorperweg 63 2597 AK Den Haag GPS 52° 06' 34" N 04° 19' 38" E Telefoon 070 374 00 00 [email protected] Met de auto Met het openbaar vervoer Uit de richting Amsterdam (A4) Vanaf NS-station Den Haag HS Afrit 8: N14 richting Leidschendam/Voorburg/Den Haag Verkeerslichten linksaf richting Wassenaar Tijdens de spitsuren 6,7 km rechtdoor richting Den Haag/Scheveningen Neem aan de achterzijde van het station spitsbus 28. Het eindpunt is TNO. Ter hoogte van een wit viaduct ziet u aan uw rechterhand de toren van TNO Verkeerslichten rechtsaf Buiten de spitsuren Nogmaals rechtsaf Neem de trein naar NS-station Den Haag CS. Volg een van de routes zoals hierna TNO ligt aan het einde van de weg, links beschreven. Uit de richting Amsterdam (A44) Vanaf NS-station Den Haag CS Neem na Schiphol de A44 naar Den Haag/Wassenaar Bij Wassenaar gaat de A44 over in de N44 Tijdens de spitsuren Volg de N44 richting Wassenaar-Zuid/Den Haag Neem tram 2 of 6 richting Leidschendam. Stap uit bij de tweede halte 'Oostinje'. Na 5 km rechtsaf, vlak voor het steenrode viaduct tegenover motel Bijhorst Neem aan de overkant van de straat bij de halte Juliana van Stolberglaan spitsbus De weg volgen richting Den Haag/Scheveningen 28. Het eindpunt is TNO. Ter hoogte van een wit viaduct ziet u aan uw rechterhand de toren van TNO Verkeerslichten rechtsaf Buiten de spitsuren Nogmaals rechtsaf Neem tram 2 of 6 richting Leidschendam. -

Verkeersplan 2017

2017 Verkeersplan 2017 Visie op een veilig, leefbaar en bereikbaar Voorschoten TITEL RAPPORT Ruimte voor een subtitel onder de koptekst versie 2.0 | december 2016 2 Samenvatting De gemeente Voorschoten streeft er naar de ideale woon- en leefomgeving te zijn en blijven. Veiligheid, leefbaarheid en bereikbaarheid vormen elementen die hier in belangrijke mate aan bijdragen. In ons verkeersbeleid richten wij ons daarbij op het verbeteren van: 1. Verkeersveiligheid 2. Leefbaarheid 3. Bereikbaarheid In ons verkeersbeleid maken we daarbij onderscheid tussen verschillende soorten verkeer, te weten voetgangers, fietsverkeer, openbaar vervoer, gemotoriseerd verkeer en tenslotte het parkeren. Het Verkeersplan Voorschoten bouwt voort op de eerder opgestelde Toekomstvisie Voorschoten 2025 en is opgesteld in een gezamenlijk proces met de economische visie, woonvisie en structuurvisie. Hierbij is nadrukkelijk gezocht naar input vanuit de samenleving. 3 Inhoudsopgave Samenvatting ........................................................................................................................................... 3 1 Inleiding ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2 De situatie in Voorschoten .............................................................................................................. 6 3 Beleidsachtergronden ................................................................................................................... 10 4 -

ALGEMENE TOELICHTING Sinds Medio 2012 Vormen De Gemeenten

ALGEMENE TOELICHTING Sinds medio 2012 vormen de gemeenten Leidschendam-Voorburg, Wassenaar, Voorschoten, Lansingerland, Pijnacker-Nootdorp en Zoetermeer de arbeidsmarktregio Zuid-Holland Centraal. Een van de doelstellingen van het Actieplan Zuid-Holland Centraal (ZHC) is het versterken en harmoniseren van de werkgeversdienstverlening. De zes gemeenten streven in dat kader onder andere naar het zoveel mogelijk op elkaar afstemmen van de re-integratie instrumenten. Binnen de managementgroep werkgeversbenadering van de ZHC-gemeenten is de wens uitgesproken om regionaal het palet aan instrumenten dat accountmanagers bij de werkgeversbenadering kunnen inzetten af te stemmen. Belangrijk onderdeel is afstemming van de voorwaarden voor en de hoogte van de loonkostensubsidies Wet werk en bijstand (WWB). Het vaststellen van het re-integratiebeleid dient lokaal plaats te vinden. Het regionale voorstel ten aanzien van de loonkostensubsidies wordt daarom in het beleid van Pijnacker-Nootdorp opgenomen door middel van het vaststellen van de eerste wijziging Uitvoeringsbesluit re-integratie 2012 gemeente Pijnacker-Nootdorp. Ten opzichte van het oorspronkelijk uitvoeringsbesluit re-integratie 2012 betekent dit concreet aanpassing van artikel 2, zevende lid van het uitvoeringsbesluit re-integratie. In het oorspronkelijke uitvoeringsbesluit re- integratie is een eenmalige loonkostensubsidie van € 4.500 opgenomen bij een dienstverband van minimaal 6 maanden. Met deze eerste wijziging wordt om dit gewijzigd in: - een eenmalige loonkostensubsidie van € 4.000 in de situatie van een halfjaarcontract - een eenmalige loonkostensubsidie van € 7.500 in de situatie van een jaarcontract of langer Het uniformeren van beleid ten aanzien van loonkostensubsidies draagt bij aan het verbeteren van de werkgeversdienstverlening in de regio. Een werkgever wil zo snel mogelijk een geschikte kandidaat vinden voor zijn vacature. -

Future Mayor Tunneling Projects in the Netherlands, 2013-2020

CONGRESS OF THE ITALIAN TUNNELLING SOCIETY “ TUNNELLING AND UNDERGROUND SPACE IN EUROPE DEVELOPMENT ” Bologna, 17, 18,19 October 2013 Future mayor tunneling projects in the Netherlands, 2013-2020 M. Lipsius, P. Jovanovic Movares Nederland B.V., Utrecht, the Netherlands ABSTRACT: The tunneling industry in the Netherlands has a long history concerning immerse tunnels as well as cut & cover tunnels. In the last 20 years the shield driven tunneling technology (TBM) has been successfully introduced in the Netherlands where the soil condition is very poor. Some of challenging projects ware successfully finished such as: high speed line tunnel Green Heart, till 2006 the biggest in the world, metro Amsterdam, 3 TBM tunnels at Betuweroute, Rotterdam to German border etc. The experience gained with the tunneling projects in the past has created the possibilities for the new projects in the Netherlands. This paper deals with the upcoming mayor tunneling highway projects in the Netherlands in the period 2013-2020 such as: Rotterdamse baan at the Hague, Rijnlandroute at the Voorschoten, Leiden and East-gate tunnel to Brainpark at Laarbeek. All these tunnels have similarities concerning their function , construction method and efficiency to their environment. Engineering company Movares showed that these tunnels are technically and financially feasible. The estimated limited higher cost of the bored tunnels makes them a attractive alternative on regular tunneltypes. 1 Introduction New infrastructure requires appropriate adjustment to its environment. Both in urban and in rural areas is often considerable public resistance present against the new highways. People really do not want to hear, see and smell the traffic which lead to creation of pressure on the planning and processes.