The State of Present-Day Domari in Jerusalem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arabic Sociolinguistics: Topics in Diglossia, Gender, Identity, And

Arabic Sociolinguistics Arabic Sociolinguistics Reem Bassiouney Edinburgh University Press © Reem Bassiouney, 2009 Edinburgh University Press Ltd 22 George Square, Edinburgh Typeset in ll/13pt Ehrhardt by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Stockport, Cheshire, and printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and East bourne A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 0 7486 2373 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 0 7486 2374 7 (paperback) The right ofReem Bassiouney to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Contents Acknowledgements viii List of charts, maps and tables x List of abbreviations xii Conventions used in this book xiv Introduction 1 1. Diglossia and dialect groups in the Arab world 9 1.1 Diglossia 10 1.1.1 Anoverviewofthestudyofdiglossia 10 1.1.2 Theories that explain diglossia in terms oflevels 14 1.1.3 The idea ofEducated Spoken Arabic 16 1.2 Dialects/varieties in the Arab world 18 1.2. 1 The concept ofprestige as different from that ofstandard 18 1.2.2 Groups ofdialects in the Arab world 19 1.3 Conclusion 26 2. Code-switching 28 2.1 Introduction 29 2.2 Problem of terminology: code-switching and code-mixing 30 2.3 Code-switching and diglossia 31 2.4 The study of constraints on code-switching in relation to the Arab world 31 2.4. 1 Structural constraints on classic code-switching 31 2.4.2 Structural constraints on diglossic switching 42 2.5 Motivations for code-switching 59 2. -

Analogy in Lovari Morphology

Analogy in Lovari Morphology Márton András Baló Ph.D. dissertation Supervisor: László Kálmán C.Sc. Doctoral School of Linguistics Gábor Tolcsvai Nagy MHAS Theoretical Linguistics Doctoral Programme Zoltán Bánréti C.Sc. Department of Theoretical Linguistics Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest Budapest, 2016 Contents 1. General introduction 4 1.1. The aim of the study of language . 4 2. Analogy in grammar 4 2.1. Patterns and exemplars versus rules and categories . 4 2.2. Analogy and similarity . 6 2.3. Neither synchronic, nor diachronic . 9 2.4. Variation and frequency . 10 2.5. Rich memory and exemplars . 12 2.6. Paradigms . 14 2.7. Patterns, prototypes and modelling . 15 3. Introduction to the Romani language 18 3.1. Discovery, early history and research . 18 3.2. Later history . 21 3.3. Para-Romani . 22 3.4. Recent research . 23 3.5. Dialects . 23 3.6. The Romani people in Hungary . 28 3.7. Dialects in Hungary . 29 3.8. Dialect diversity and dialectal pluralism . 31 3.9. Current research activities . 33 3.10. Research of Romani in Hungary . 34 3.11. The current research . 35 4. The Lovari sound system 37 4.1. Consonants . 37 4.2. Vowels . 37 4.3. Stress . 38 5. A critical description of Lovari morphology 38 5.1. Nominal inflection . 38 5.1.1. Gender . 39 5.1.2. Animacy . 40 5.1.3. Case . 42 5.1.4. Additional features. 47 5.2. Verbal inflection . 50 5.2.1. The present tense . 50 5.2.2. Verb derivation. 54 5.2.2.1. Transitive derivational markers . -

Map by Steve Huffman; Data from World Language Mapping System

Svalbard Greenland Jan Mayen Norwegian Norwegian Icelandic Iceland Finland Norway Swedish Sweden Swedish Faroese FaroeseFaroese Faroese Faroese Norwegian Russia Swedish Swedish Swedish Estonia Scottish Gaelic Russian Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Latvia Latvian Scots Denmark Scottish Gaelic Danish Scottish Gaelic Scottish Gaelic Danish Danish Lithuania Lithuanian Standard German Swedish Irish Gaelic Northern Frisian English Danish Isle of Man Northern FrisianNorthern Frisian Irish Gaelic English United Kingdom Kashubian Irish Gaelic English Belarusan Irish Gaelic Belarus Welsh English Western FrisianGronings Ireland DrentsEastern Frisian Dutch Sallands Irish Gaelic VeluwsTwents Poland Polish Irish Gaelic Welsh Achterhoeks Irish Gaelic Zeeuws Dutch Upper Sorbian Russian Zeeuws Netherlands Vlaams Upper Sorbian Vlaams Dutch Germany Standard German Vlaams Limburgish Limburgish PicardBelgium Standard German Standard German WalloonFrench Standard German Picard Picard Polish FrenchLuxembourgeois Russian French Czech Republic Czech Ukrainian Polish French Luxembourgeois Polish Polish Luxembourgeois Polish Ukrainian French Rusyn Ukraine Swiss German Czech Slovakia Slovak Ukrainian Slovak Rusyn Breton Croatian Romanian Carpathian Romani Kazakhstan Balkan Romani Ukrainian Croatian Moldova Standard German Hungary Switzerland Standard German Romanian Austria Greek Swiss GermanWalser CroatianStandard German Mongolia RomanschWalser Standard German Bulgarian Russian France French Slovene Bulgarian Russian French LombardRomansch Ladin Slovene Standard -

Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo Iouo

Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 1 A’ou [aou] Iouo China 2 Abai Sungai [abf] Iouo Malaysia 3 Abaza [abq] Iouo Russia, Turkey 4 Abinomn [bsa] Iouo Indonesia 5 Abkhaz [abk] Iouo Georgia, Turkey 6 Abui [abz] Iouo Indonesia 7 Abun [kgr] Iouo Indonesia 8 Aceh [ace] Iouo Indonesia 9 Achang [acn] Iouo China, Myanmar 10 Ache [yif] Iouo China 11 Adabe [adb] Iouo East Timor 12 Adang [adn] Iouo Indonesia 13 Adasen [tiu] Iouo Philippines 14 Adi [adi] Iouo India 15 Adi, Galo [adl] Iouo India 16 Adonara [adr] Iouo Indonesia Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Russia, Syria, 17 Adyghe [ady] Iouo Turkey 18 Aer [aeq] Iouo Pakistan 19 Agariya [agi] Iouo India 20 Aghu [ahh] Iouo Indonesia 21 Aghul [agx] Iouo Russia 22 Agta, Alabat Island [dul] Iouo Philippines 23 Agta, Casiguran Dumagat [dgc] Iouo Philippines 24 Agta, Central Cagayan [agt] Iouo Philippines 25 Agta, Dupaninan [duo] Iouo Philippines 26 Agta, Isarog [agk] Iouo Philippines 27 Agta, Mt. Iraya [atl] Iouo Philippines 28 Agta, Mt. Iriga [agz] Iouo Philippines 29 Agta, Pahanan [apf] Iouo Philippines 30 Agta, Umiray Dumaget [due] Iouo Philippines 31 Agutaynen [agn] Iouo Philippines 32 Aheu [thm] Iouo Laos, Thailand 33 Ahirani [ahr] Iouo India 34 Ahom [aho] Iouo India 35 Ai-Cham [aih] Iouo China 36 Aimaq [aiq] Iouo Afghanistan, Iran 37 Aimol [aim] Iouo India 38 Ainu [aib] Iouo China 39 Ainu [ain] Iouo Japan 40 Airoran [air] Iouo Indonesia 1 Asia No. Language [ISO 639-3 Code] Country (Region) 41 Aiton [aio] Iouo India 42 Akeu [aeu] Iouo China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, -

Salvation Linguist’

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 3. Editor: Peter K. Austin Language contact, language endangerment, and the role of the ‘salvation linguist’ YARON MATRAS Cite this article: Yaron Matras (2005). Language contact, language endangerment, and the role of the ‘salvation linguist’. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description, vol 3. London: SOAS. pp. 225-251 Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/043 This electronic version first published: July 2014 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Terms of use: http://www.elpublishing.org/terms Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Language contact, language endangerment, and the role of the ‘salvation linguist’ Yaron Matras 1. Preface In the first part of this paper I address concerns in respect of certain images and notions that surround the current agenda of the study of endangered -

Data Source : Todd M. Johnson, Ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014)

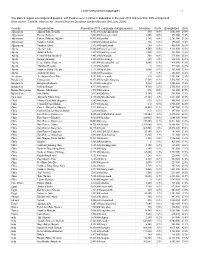

Least evangelized megapeoples 1 The globe’s largest unevangelized peoples: 247 Peoples over 1 million in population in the year 2015 and less than 50% evangelized. Data source : Todd M. Johnson, ed., World Christian Database (Leiden/Boston: Brill, July, 2014). Country People Name Population 2015 Language Autoglossonym Christians Chr% Evangelized Ev% Afghanistan Afghani Tajik (Tadzhik) 8,002,000 tajiki-afghanistan 800 0.0% 1,601,000 20.0% Afghanistan Hazara (Berberi) 2,604,000 hazaragi central 1,000 0.0% 574,000 22.0% Afghanistan Pathan (Pukhtun, Afghani) 11,995,000 pashto 2,400 0.0% 2,761,000 23.0% Afghanistan Southern Pathan 1,600,000 paktyan-pashto 320 0.0% 198,000 12.4% Afghanistan Southern Uzbek 2,590,000 özbek south 260 0.0% 466,000 18.0% Algeria Algerian Arab 23,684,000 jaza'iri general 9,500 0.0% 9,128,000 38.5% Algeria Arabized Berber 1,219,000 jaza'iri general 1,200 0.1% 544,000 44.6% Algeria Central Shilha (Beraber) 1,483,000 ta-mazight 300 0.0% 378,000 25.5% Algeria Hamyan Bedouin 2,836,000 hassaniyya 280 0.0% 582,000 20.5% Algeria Lesser Kabyle (Eastern) 1,002,000 tha-qabaylith east 5,000 0.5% 421,000 42.0% Algeria Shawiya (Chaouia) 2,129,000 shawiya 0 0.0% 479,000 22.5% Algeria Southern Shilha (Shleuh) 1,113,000 ta-shelhit 1,000 0.1% 363,000 32.6% Algeria Tajakant Bedouin 1,666,000 hassaniyya 0 0.0% 262,000 15.8% Azerbaijan Azerbaijani (Azeri Turk) 8,182,000 azeri north 820 0.0% 2,701,000 33.0% Bangladesh Chittagonian 13,475,000 bangla-chittagong 17,500 0.1% 5,542,000 41.1% Bangladesh Rangpuri (Rajbansi) 10,170,000 rajbangshi -

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afghan, Tajik in Afghanistan Aimaq in Afghanistan

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Afghan, Tajik in Afghanistan Aimaq in Afghanistan Population: 10,831,000 Population: 1,632,000 World Popl: 11,236,800 World Popl: 2,129,300 Total Countries: 3 Total Countries: 5 People Cluster: Tajik People Cluster: Persian Main Language: Dari Main Language: Aimaq Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.01% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.01% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Complete Bible Scripture: Translation Needed www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Chuck Holton Source: Tomas Balkus "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Hazara in Afghanistan Pashtun, Northern in Afghanistan Population: 3,981,000 Population: 2,813,000 World Popl: 4,753,700 World Popl: 29,660,600 Total Countries: 8 Total Countries: 18 People Cluster: Persian People Cluster: South Asia Muslim - Pashtun Main Language: Hazaragi Main Language: Pashto, Northern Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.03% Evangelicals: 0.01% Chr Adherents: 0.03% Chr Adherents: 0.01% Scripture: Portions Scripture: Complete Bible Source: Anonymous www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Jeremy Weate "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Pashtun, Southern in Afghanistan Turkmen in Afghanistan Population: 9,881,000 -

On Romani Origins and Identity

ON ROMANI ORIGINS AND IDENTITY Ian Hancock The Romani Archives and Documentation Center The University of Texas at Austin 1 “A geneticist’s summary of [our] data would describe the Gypsies as a conglomerate of Asian populations . unambiguous proof of the Indian ancestry of the Gypsies comes from three genetic marker systems . found on the same ancestral chromosomal background in Gypsy, Indian and Pakistani subjects. While confirming the centuries-old linguistic theory of the Indian origins is no great triumph for modern genetic research, the major, unexpected and most significant result of these studies is the strong evidence of the common descent of all Gypsies regardless of declared group identity, country of residence and rules of endogamy . The Gypsy group was born in Europe. All marker systems suggest that the earliest splits occurred 20 to 24 generations ago, i.e . from the late 13 th century onwards” (Kalaydjieva et al ., 2005:1085-6). 2 hose of you familiar with my work know that it has taken a circuitous route over the years T in an ongoing effort to refine it, and no doubt it will be modified further as it continues. Thus in my earliest writing I supported a fifth-century exodus from India and accepted the established three-way Rom-Dom-Lom split; I no longer do. I argued for a wholly non-“Aryan” ancestry, but no longer believe this to have been the case nor, indeed, that “Aryan” is even a genetically relevant label. I saw the migration from India to Anatolia as having been a slow one, consisting of a succession of military encounters with different non-Indian populations; I no longer think that it happened in that way. -

Jerusalem Domari Yaron Matras University of Manchester

Chapter 23 Jerusalem Domari Yaron Matras University of Manchester Jerusalem Domari is the only variety of Domari for which there is comprehensive documentation. The language shows massive influence of Arabic in different areas of structure – quite possibly the most extensive structural impact of Arabic on any other language documented to date. Arabic influence on Jerusalem Domari raises theoretical questions around key concepts of contact-induced change as well as the relations between systems of grammar and the components of multilingual repertoires; these are dealt with briefly in the chapter, along with the notions of fusion, compartmentalisation of paradigms, and bilingual suppletion. 1 Historical development and current state Domari is a dispersed, non-territorial minority language of Indo-Aryan origin that is spoken by traditionally itinerant (peripatetic) populations throughout the Middle East. Fragmented attestations of the language place it as far north as Azer- baijan and as far south as Sudan. The self-appellation dōm is cognate with those of the řom (Roma or Romanies) of Europe and the lom of the Caucasus and eastern Anatolia. All three populations show linguistic resources of Indo-Aryan origin (which in the case of the Lom are limited to vocabulary), as well as traditions of a mobile service economy, and are therefore all believed to have descended from itinerant service castes in India known as ḍom. Some Domari-speaking popula- tions are reported to use additional names, including qurbāṭi (Syria and Lebanon), mıtrıp or karači (Turkey and northern Iraq) and bahlawān (Sudan), while the surrounding Arabic-speaking populations usually refer to them as nawar, ɣaǧar or miṭribiyya. -

Northern Domari Bruno Herin Inalco, IUF

Chapter 22 Northern Domari Bruno Herin Inalco, IUF This chapter provides an overview of the linguistic outcomes of contact between Arabic and Northern Domari. Northern Domari is a group of dialects spoken in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey. It remained until very recently largely un- explored. This article presents unpublished first-hand linguistic data collected in Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and Turkey. It focuses on the Beirut/Damascus variety, with references to the dialects spoken in northern Syria and southern Turkey. 1 Current state and historical development Domari is an Indic language spoken by the Doms in various countries of the Middle East. The Doms are historically itinerant communities who specialize in service economies. This occupational profile led the lay public to call them the Middle Eastern Gypsies. Common occupations are informal dentistry, metal- work, instrument crafting, entertainment and begging. Most claim Sunni Islam as their religion, with various degrees of syncretic practices. Although most have given up their semi-nomadic lifestyle and settled in the periphery of urban cen- tres, mobility is still a salient element in the daily lives of many Doms. The ethnonym Dom is mostly unknown to non-Doms, who refer to them with various appellations such as nawar, qurbāṭ or qarač. The Standard Arabic word ɣaǧar for ‘Gypsy’ is variably accepted by the Doms, who mostly understand with this term European Gypsies. All these appellations are exonyms and the only endonym found across all communities is dōm. Only the Gypsies of Egypt, it seems, use a reflex of ɣaǧar to refer to themselves. From the nineteenth century onwards, European travellers reported the exis- tence of Domari in the shape of word lists collected in the Caucasus, Iran, Iraq and the Levant (see Herin 2012 for a discussion of these sources). -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All People Groups & LR-Upgs of Eurasia

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-Unreached People Groups of Eurasia AGWM ed. Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net I give credit & thanks to Asia Harvest & Create International for permission to use their people group photos. 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all People Groups & LR-UPGs of Eurasia (India & South Asia = separate DPG) SUMMARY: 2,061 total People Groups; 1,462 LR-UPG (this DPG) LR-UPG = 2% or less Evangelical & 5% or less Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country Downloaded from www.joshuaproject.net September 2020 "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" Luke 10:2, Jesus told them, "The harvest is plentiful, but the workers are few. Ask the Lord of the harvest, therefore, to send out workers into his harvest field." Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commands us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. -

Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 Code for Comprehensive Coverage of Languages

© ISO 2003 — All rights reserved ISO TC 37/SC 2 N 292 Date: 2003-08-29 ISO/CD 639-3 ISO TC 37/SC 2/WG 1 Secretariat: ON Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages Codes pour la représentation de noms de langues ― Partie 3: Code alpha-3 pour un traitement exhaustif des langues Warning This document is not an ISO International Standard. It is distributed for review and comment. It is subject to change without notice and may not be referred to as an International Standard. Recipients of this draft are invited to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent rights of which they are aware and to provide supporting documentation. Document type: International Standard Document subtype: Document stage: (30) Committee Stage Document language: E C:\Documents and Settings\여동희\My Documents\작업파일\ISO\Korea_ISO_TC37\심의문서\심의중문서\SC2\N292_TC37_SC2_639-3 CD1 (E) (2003-08-29).doc STD Version 2.1 ISO/CD 639-3 Copyright notice This ISO document is a working draft or committee draft and is copyright-protected by ISO. While the reproduction of working drafts or committee drafts in any form for use by participants in the ISO standards development process is permitted without prior permission from ISO, neither this document nor any extract from it may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form for any other purpose without prior written permission from ISO. Requests for permission to reproduce this document for the purpose of selling it should be addressed as shown below or to ISO's member body in the country of the requester: [Indicate the full address, telephone number, fax number, telex number, and electronic mail address, as appropriate, of the Copyright Manger of the ISO member body responsible for the secretariat of the TC or SC within the framework of which the working document has been prepared.] Reproduction for sales purposes may be subject to royalty payments or a licensing agreement.