Lockwood, Samuel D 1825-1848

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coles Family Papers 1458 Finding Aid Prepared by Amanda Fellmeth

Coles Family Papers 1458 Finding aid prepared by Amanda Fellmeth. Last updated on November 09, 2018. Historical Society of Pennsylvania 2010 Coles Family Papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................5 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - Coles Family Papers Summary Information Repository Historical Society of Pennsylvania Creator Coles, Edward, 1786-1868. Title -

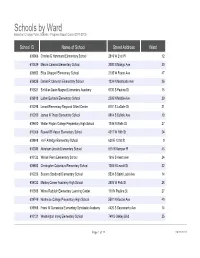

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

A Letter from Jefferson to Edward Coles

Educational materials were developed through the Making Master Teachers in Howard County Program, a partnership between Howard County Public School System and the Center for History Education at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Teacher Page: Resource Sheet #09 Source: Letter From Thomas Jefferson to Edward Coles. Monticello: August 25, 1814, Jefferson’s Farm Book. Note: Edward Coles was born into a wealthy slave-owning family in Albemarle County, Virginia. Coles studied at the College of William & Mary and was convinced that slavery was wrong. He sought for many years to find a way to free the slaves he inherited from his father; one of the wealthiest men in what was then the western frontier of Virginia. He became the second governor of Illinois, serving from 1822 to 1826. He was influential in opposing a movement to make Illinois a slave state in its early years. He often corresponded with Jefferson at Monticello. Document Analysis: 1. How does Jefferson feel about slaves and African-Americans when considering their capabilities as citizens? Jefferson equates African-Americans to children, unable to take care of themselves and destined to become a burden to society as free persons. 2. How does Jefferson react to the possibility that, if slavery is abolished, inter-racial offspring (amalgamation) may occur? It would be a horrible condition, one that which “no lover of his country, no lover of excellence in the human character can innocently consent.” 3. What does Jefferson believe that slaves will do, if they are not used actively as laborers? Non-working slaves could create a problem for the society at large. -

Former Governors of Illinois

FORMER GOVERNORS OF ILLINOIS Shadrach Bond (D-R*) — 1818-1822 Illinois’ first Governor was born in Maryland and moved to the North - west Territory in 1794 in present-day Monroe County. Bond helped organize the Illinois Territory in 1809, represented Illinois in Congress and was elected Governor without opposition in 1818. He was an advo- cate for a canal connecting Lake Michigan and the Illinois River, as well as for state education. A year after Bond became Gov ernor, the state capital moved from Kaskaskia to Vandalia. The first Illinois Constitution prohibited a Governor from serving two terms, so Bond did not seek reelection. Bond County was named in his honor. He is buried in Chester. (1773- 1832) Edward Coles (D-R*) — 1822-1826 The second Illinois Governor was born in Virginia and attended William and Mary College. Coles inherited a large plantation with slaves but did not support slavery so he moved to a free state. He served as private secretary under President Madison for six years, during which he worked with Thomas Jefferson to promote the eman- cipation of slaves. He settled in Edwardsville in 1818, where he helped free the slaves in the area. As Governor, Coles advocated the Illinois- Michigan Canal, prohibition of slavery and reorganization of the state’s judiciary. Coles County was named in his honor. He is buried in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (1786-1868) Ninian Edwards (D-R*) — 1826-1830 Before becoming Governor, Edwards was appointed the first Governor of the Illinois Territory by President Madison, serving from 1809 to 1818. Born in Maryland, he attended college in Pennsylvania, where he studied law, and then served in a variety of judgeships in Kentucky. -

The Impeachment and Removal of Governor Rod Blagojevich

A JUST CAUSE The Impeachment and Removal of Governor Rod Blagojevich Bernard H. Sieracki Foreword by Jim Edgar Southern Illinois University Press Carbondale Contents Foreword ix Jim Edgar Prologue 1 1. The Crisis Erupts 6 2. Cause for Impeachment 19 3. The House Investigation 33 4. The Impeachment Resolution 85 5. Senate Preparations 105 6. The Trial 113 7. The Last Day 160 Epilogue 190 Notes 195 Index 209 Gallery starting on page 95 Prologue n Tuesday, December 9, 2008, a gray dawn arrived over Illinois, bringing an intermittent rain and a chill in the air. It was one of Othose damp, early winter days when the struggle between fall and winter seems finally resolved, and people go on with a sense of acceptance. There was nothing special about the dawning of this day, but that would rapidly change. In the early morning hours an FBI arrest team arrived at the Chicago home of Governor Rod Blagojevich and took him quickly into custody. The arrest was conducted like a raid. The governor was not given advance warning or the courtesy of being able to turn himself in; rather, he was snatched in the night like a common criminal. Wearing a jogging suit and handcuffs, the stunned governor was photographed being led away by federal agents. Word of the governor’s arrest quickly spread throughout the state and began a political crisis that would grip Illinois for the next seven weeks and three days. 1 Prologue With helicopters hovering overhead, broadcasting events on live televi- sion, news crews followed the caravan of police and federal vehicles trans- porting the governor through the streets of Chicago, first to a federal lockup facility on the city’s near west side and then downtown to federal court. -

Sources of Mormon History in Illinois, 1839-48: an Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University

BIBLIOGRAPHIC CONTRIBUTIONS NO. Sources of Mormon History in Illinois, 1839-48: An Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University Compiled by STANLEY B. KIMBALL 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, 1966 The Library SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Carbondale—Edwardsville Bibliographic Contributions No. 1 SOURCES OF MORMON HISTORY IN ILLINOIS, 1839-48 An Annotated Catalog of the Microfilm Collection at Southern Illinois University 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, 1966 Compiled by Stanley B. Kimball Central Publications Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois ©2014 Southern Illinois University Edwardsville 2nd edition, revised and enlarged, May, 1966 FOREWORD In the course of developing a book and manuscript collection and in providing reference service to students and faculty, a univeristy library frequently prepares special bibliographies, some of which may prove to be of more than local interest. The Bibliographic Contributions series, of which this is the first number, has been created as a means of sharing the results of such biblio graphic efforts with our colleagues in other universities. The contribu tions to this series will appear at irregular intervals, will vary widely in subject matter and in comprehensiveness, and will not necessarily follow a uniform bibliographic format. Because many of the contributions will be by-products of more extensive research or will be of a tentative nature, the series is presented in this format. Comments, additions, and corrections will be welcomed by the compilers. The author of the initial contribution in the series is Associate Professor of History of Southern Illinois University, Edwardsville, Illinois. He has been engaged in research on the Nauvoo period of the Mormon Church since he came to the university in 1959 and has published numerous articles on this subject. -

The Expansion of Democracy in the Jacksonian Era

“THE INTERESTS OF THE MANY”: THE EXPANSION OF DEMOCRACY IN THE JACKSONIAN ERA An Online Professional Development Seminar from the Florida Virtual School and the National Humanities Center Assigned Readings Notes by Reeve Huston Associate Professor of History Duke University The following assigned texts are incorporated in the notes below. • New York voting requirements, 1777 • Petition of citizens of Richmond (VA) to state constitutional convention, 1829-30 • Warren Dutton, standard argument against expanded suffrage, 1820 • New York convention on voting, 1821 • Letter from Edward Patchell to Andrew Jackson • Letter from Martin Van Buren to Thomas Ritchie, 1827 • Thomas Ford, History of Illinois, 1854 • New York Democratic State Committee, “Plan of Organization,” 1844 • Cartoon: Rich v. Poor, Satan v. Liberty NOTES AND ASSIGNED TEXTS Re-establishing and Extending Partisan Democracy Nobody had ever seen anything like it. For the entire previous day, people had poured into Washington, D.C., to see their new president, Andrew Jackson, sworn in. By ten in the morning of the inauguration, the streets were jammed. Up to this point, presidential inaugurations had been quiet affairs. Now, according to Margaret Bayard Smith, the wife of a Maryland senator and a leading member of the capital’s gentry, the streets were jammed with fancy carriages and farmer’s carts, “filled with women and children, some in finery and some in rags.” After the new president swore his oath and gave his speech, a long procession of “country men, farmers, gentlemen, . boys, women and children, black and white” followed him to the White House and descended upon the presidential reception. -

Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 21 (2012-2013) Issue 4 Article 6 May 2013 Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary Terry L. Meyers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Repository Citation Terry L. Meyers, Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary, 21 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 1215 (2013), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol21/iss4/6 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THINKING ABOUT SLAVERY AT THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY Terry L. Meyers* I. POST-RECONSTRUCTION AND ANTE-BELLUM Distorting, eliding, falsifying . a university’s memory can be as tricky as a person’s. So it has been at the College of William and Mary, often in curious ways. For example, those delving into its history long overlooked the College’s eighteenth century plantation worked by slaves for ninety years to raise tobacco.1 Although it seems easy to understand that omission, it is harder to understand why the College’s 1760 affiliation with a school for black children2 was overlooked, or its president in 1807 being half-sympathetic to a black man seeking to sit in on science lectures,3 or its awarding an honorary degree to the famous English abolitionist Granville Sharp in 1791,4 all indications of forgotten anti-slavery thought at the College. To account for these memory lapses, we must look to a pivotal time in the late- nineteenth and early-twentieth century when the College, Williamsburg, and Virginia * Chancellor Professor of English, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, [email protected]. -

The Letters of Thomas Jefferson

THE LETTERS OF THOMAS JEFFERSON The World of Thomas Jefferson as revealed in some of his 19,000+ letters This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA Thomas Jefferson: •“If you want to understand my life, read the letters I received and the letters I wrote.” IMPORTANT ANNOUNCEMENT! There are no written notes for this class but… This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA-NC WHILE WE’RE WAITING… • I’M GOING TO GIVE YOU A GREAT DEAL OF INFORMATION ABOUT JEFFERSON BUT…. •DON’T WORRY! This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY • I’M GOING TO PUT THIS ENTIRE CLASS ONLINE AFTER WE FINISH SO FEEL FREE TO TAKE NOTES OR NOT AS YOU WISH. • IF YOU HAVE FOLLOW-UP COMMENTS OR QUESTIONS FOR ME AFTER TODAY, YOU CAN REACH ME AT • [email protected] FIRST THE FACTS! • 1. Thomas Jefferson really, really liked books. The third president, after his retirement, sold his library TEN FACTS of 6,500 volumes to the Library of ABOUT Congress after it was ransacked by THOMAS the British. Jefferson needed the cash to pay off debts, but he started JEFFERSON buying more books. "I cannot live without books," he told John Adams. 2. Jefferson the economist. Jefferson was deeply engaged in economic theory, which he learned to love during his time in France. He was a friend and translator to leading European theorists; he believed in the free market policies; and he opposed bank notes as currency. • 3. Jefferson the architect. He designed the rotunda for the University of Virginia, his own home at Monticello, and the Virginia State Capitol in Richmond. -

Edward Coles Emancipation Leader Sunday, Feb. 18, 2 P.M. MCHS

Madison County Historical Society MCHS News Jan 2018 Opening Doors to Madison County History Vol. 6 No. 1 January, 2013 Vol. 1, No. 1 715 N Main Street Edward Coles MCHS CELEBRATES Edwardsville, IL Emancipation Leader 62025 ILLINOIS BICENTENNIAL Sunday, Feb. 18, 2 p.m. On Dec. 3, 1818, Illinois became the twenty-first Archival Library state in the United States of America. In celebration Hours: Madison County Archival Library of the state’s 200th anniversary, the MCHS News will Wed-Fri 9 am - 4 pm Museum Superintendent Jon Parkin place an emphasis on early Illinois and Madison Sunday 1 pm - 4 pm will present a program on Edward Coles County history for our six 2018 issues. at the Madison County Archival Library This month’s articles, by Museum Superinten- Group Tours Available on Sunday, Feb. 18 at 2 p.m.. dent Jon Parkin, explore how land was distributed in Many historians believe that if not for the territory, the economic panic of 1819 and early Museum : Edward Coles, Illinois may not have stagecoach routes. Later this year the newsletter will The museum is been a free state. His contributions to explore the Illinois Centennial Celebration of 1918, currently closed for renovation Illinois history are remembered in Abraham Lincoln in Madison County, the Old Six Madison County with a memorial in- Mile House in Granite City, and other stories in stalled on Route 157 by the State of celebration of the state’s Bicentennial anniversary. Phone: Illinois in 1929 and with a Illinois State 618-656-7569 Historical Society marker on the grounds EARLY ILLINOIS SETTLEMENT of the Manny Jackson Center on North By Jon Parkin, Museum Superintendent Main Street in Edwardsville. -

Chronology of Illinois History 20,000 B.C.E.-8,000 B.C.E

CHRONOLOGY OF ILLINOIS HISTORY 20,000 B.C.E.-8,000 B.C.E. — Paleo-Indians migrate into Illinois. They gather wild plants and hunt animals, including the giant bison, wooly mammoth and mastodon. 8,000-1,000 B.C.E. — During the Archaic Period, Illinois inhabitants cultivate plants and create specialized tools for hunting and fishing. 700-1500 — Mississippian Native American culture builds large planned towns with flat- topped temple mounds along rivers. Near present-day Collinsville, 120 mounds are built in a city with a population of more than 20,000. Monks Mound is the largest prehistoric earthen construction in North America. Extraction of salt from Saline County begins. 1655 — The Iroquois invade Illinois and defeat the Illini. Native American wars continue sporadically for 120 years. 1673 — The Illiniwek (tribe of men), a Native American confederation consisting of Cahokias, Kaskaskias, Mitchagamies, Peorias and Tamaroas, encounter French ex plor - ers who refer to the people and country as “Illinois.” Frenchmen Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet descend the Mississippi to Arkansas and return to Lake Michigan by way of the Illinois River. 1680 — La Salle builds Fort Creve coeur on the Illinois River near pres ent Peoria. SEPTEMBER — The Iroquois chase the Illini from Illinois. Twelve hundred Tamaroas are tortured and killed. 1682 — La Salle builds Fort St. Louis on Starved Rock. 1691-92 — Tonti and La Forest build the second Fort St. Louis, better known as Fort Pimitoui, on Lake Peoria. 1696 — Jesuit priest Francois Pinet organizes the Mission of the Guardian Angel, the first permanent place of worship in the pre-Chicago wilderness. -

Groundbreaking Ceremony: June 12, 1971 Governors State University

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship University Anniversaries & Historical Documents University Archives 6-12-1971 Groundbreaking Ceremony: June 12, 1971 Governors State University Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/anniv Recommended Citation Governors State University, "Groundbreaking Ceremony: June 12, 1971" (1971). University Anniversaries & Historical Documents. Paper 45. http://opus.govst.edu/anniv/45 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Anniversaries & Historical Documents by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 7969 Governors State University Park Forest South, Illinois 60466 OL O PROGRAM Music Thornton Community College Jazz Band Mr. Don Kramer, Director Invocation Rev. David L. Brecht, 0. S. A., Academic Dean, Tolentine College The National Anthem Welcome Dr. William E. Engbretson, President, Governors State University Speakers Mr. Kenneth E. Koenig, Village President Park Forest South, Illinois Rep. John J. Houlihan, Illinois State Legislature Sen. Jack E. Walker, Illinois State Legislature Dr. Geraldine Williams, Director of Academic Development, College of Business and Public Service Louise Bigott, student Samuel DeBose, student Mr. Royal A. Stipes, Jr., Chairman, Board of Governors of State Colleges and Universities Address The Honorable Richard B. Ogilvie, Governor, State of Illinois Groundbreaking Box Luncheon BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF STATE Governors State University was estab- COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES lished by the State of Illinois on July 17, 1969, as a new model, upper division and graduate institution of higher learning.