Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coles Family Papers 1458 Finding Aid Prepared by Amanda Fellmeth

Coles Family Papers 1458 Finding aid prepared by Amanda Fellmeth. Last updated on November 09, 2018. Historical Society of Pennsylvania 2010 Coles Family Papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................5 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 - Page 2 - Coles Family Papers Summary Information Repository Historical Society of Pennsylvania Creator Coles, Edward, 1786-1868. Title -

Image Credits, the Making of African

THE MAKING OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY: VOL. I, 1500-1865 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION The Making of African American Identity: Vol. I, 1500-1865 IMAGE CREDITS Items listed in chronological order within each repository. ALABAMA DEPT. of ARCHIVES AND HISTORY. Montgomery, Alabama. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Physical and Political Map of the Southern Division of the United States, map, Boston: William C. Woodbridge, 1843; adapted to Woodbridges Geography, 1845; map database B-315, filename: se1845q.sid. Digital image courtesy of Alabama Maps, University of Alabama. ALLPORT LIBRARY AND MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS. State Library of Tasmania. Hobart, Tasmania (Australia). WEBSITE Reproduced by permission of the Tasmanian Archive & Heritage Office. —Mary Morton Allport, Comet of March 1843, Seen from Aldridge Lodge, V. D. Land [Tasmania], lithograph, ca. 1843. AUTAS001136168184. AMERICAN TEXTILE HISTORY MUSEUM. Lowell, Massachusetts. WEBSITE Reproduced by permission. —Wooden snap reel, 19th-century, unknown maker, color photograph. 1970.14.6. ARCHIVES OF ONTARIO. Toronto, Ontario, Canada. WEBSITE In the public domain; reproduced courtesy of Archives of Ontario. —Letter from S. Wickham in Oswego, NY, to D. B. Stevenson in Canada, 12 October 1850. —Park House, Colchester, South, Ontario, Canada, refuge for fugitive slaves, photograph ca. 1950. Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F2076-16-6. —Voice of the Fugitive, front page image, masthead, 12 March 1854. F 2076-16-935. —Unidentified black family, tintype, n.d., possibly 1850s; Alvin D. McCurdy fonds, F 2076-16-4-8. ASBURY THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY. Wilmore, Kentucky. Permission requests submitted. –“Slaves being sold at public auction,” illustration in Thomas Lewis Johnson, Twenty-Eight Years a Slave, or The Story of My Life in Three Continents, 1909, p. -

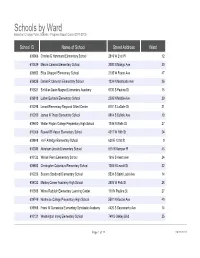

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012)

Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) School ID Name of School Street Address Ward 609966 Charles G Hammond Elementary School 2819 W 21st Pl 12 610539 Marvin Camras Elementary School 3000 N Mango Ave 30 609852 Eliza Chappell Elementary School 2135 W Foster Ave 47 609835 Daniel R Cameron Elementary School 1234 N Monticello Ave 26 610521 Sir Miles Davis Magnet Elementary Academy 6730 S Paulina St 15 609818 Luther Burbank Elementary School 2035 N Mobile Ave 29 610298 Lenart Elementary Regional Gifted Center 8101 S LaSalle St 21 610200 James N Thorp Elementary School 8914 S Buffalo Ave 10 609680 Walter Payton College Preparatory High School 1034 N Wells St 27 610056 Roswell B Mason Elementary School 4217 W 18th St 24 609848 Ira F Aldridge Elementary School 630 E 131st St 9 610038 Abraham Lincoln Elementary School 615 W Kemper Pl 43 610123 William Penn Elementary School 1616 S Avers Ave 24 609863 Christopher Columbus Elementary School 1003 N Leavitt St 32 610226 Socorro Sandoval Elementary School 5534 S Saint Louis Ave 14 609722 Manley Career Academy High School 2935 W Polk St 28 610308 Wilma Rudolph Elementary Learning Center 110 N Paulina St 27 609749 Northside College Preparatory High School 5501 N Kedzie Ave 40 609958 Frank W Gunsaulus Elementary Scholastic Academy 4420 S Sacramento Ave 14 610121 Washington Irving Elementary School 749 S Oakley Blvd 25 Page 1 of 28 09/23/2021 Schools by Ward Based on Chicago Public Schools - Progress Report Cards (2011-2012) 610352 Durkin Park Elementary School -

Virginia Historical Society the CENTER for VIRGINIA HISTORY

Virginia Historical Society THE CENTER FOR VIRGINIA HISTORY ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2004 ANNUAL MEETING, 23 APRIL 2005 Annual Report for 2004 Introduction Charles F. Bryan, Jr. President and Chief Executive Officer he most notable public event of 2004 for the Virginia Historical Society was undoubtedly the groundbreaking ceremony on the first of TJuly for our building expansion. On that festive afternoon, we ushered in the latest chapter of growth and development for the VHS. By turning over a few shovelsful of earth, we began a construction project that will add much-needed programming, exhibition, and storage space to our Richmond headquarters. It was a grand occasion and a delight to see such a large crowd of friends and members come out to participate. The representative individuals who donned hard hats and wielded silver shovels for the formal ritual of begin- ning construction stood in for so many others who made the event possible. Indeed, if the groundbreaking was the most important public event of the year, it represented the culmination of a vast investment behind the scenes in forward thinking, planning, and financial commitment by members, staff, trustees, and friends. That effort will bear fruit in 2006 in a magnifi- cent new facility. To make it all happen, we directed much of our energy in 2004 to the 175th Anniversary Campaign–Home for History in order to reach the ambitious goal of $55 million. That effort is on track—and for that we can be grateful—but much work remains to be done. Moreover, we also need to continue to devote resources and talent to sustain the ongoing programs and activities of the VHS. -

1823 Journal of General Convention

Journal of the Proceedings of the Bishops, Clergy, and Laity of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America in a General Convention 1823 Digital Copyright Notice Copyright 2017. The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America / The Archives of the Episcopal Church All rights reserved. Limited reproduction of excerpts of this is permitted for personal research and educational activities. Systematic or multiple copy reproduction; electronic retransmission or redistribution; print or electronic duplication of any material for a fee or for commercial purposes; altering or recompiling any contents of this document for electronic re-display, and all other re-publication that does not qualify as fair use are not permitted without prior written permission. Send written requests for permission to re-publish to: Rights and Permissions Office The Archives of the Episcopal Church 606 Rathervue Place P.O. Box 2247 Austin, Texas 78768 Email: [email protected] Telephone: 512-472-6816 Fax: 512-480-0437 JOURNAL .. MTRJI OJr TllII "BISHOPS, CLERGY, AND LAITY O~ TIU; PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCH XII TIIJ! UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Xif A GENERAL CONVENTION, Held in St. l'eter's Church, in the City of Philadelphia, from the 20th t" .the 26th Day of May inclusive, A. D. 1823. NEW· YORK ~ PlllNTED BY T. lit J. SWURDS: No. 99 Pearl-street, 1823. The Right Rev. William White, D. D. of Pennsylvania, Pre siding Bishop; The Right Rev. John Henry Hobart, D. D. of New-York, The Right Rev. Alexander Viets Griswold, D. D. of the Eastern Diocese, comprising the states of Maine, New Hampshire, Massachusct ts, Vermont, and Rhode Island, The Right Rev. -

C:\Users\User1\Documents

Date:June 3,2021 Last Web Update:September 2,2020 WHITLOCK FAMILY RESEARCH - PRINTED & ORIGINAL SOURCES R0001/20 Research by Wilfred John Whitlock - Whitlocks of Langtree, Devon to 1968 R0002/7 Whitlocks of Devon research by J.R. Powell Nov.1910 R0002A/5 Whitlocks of Warkleigh, Langtree, Parkham, Devon from Kate Johnson (nee Whitlock) June 1968 R0003/6 Photocopies of Whitelocke entries in Biographical Dictionary R0004/1 Whitlocks of Warkleigh with connection to Whitlocks of Illinois by Frank M. Whitlock 1936 R0004A/1 Whitlocks of Warkleigh descent from John Lake of Bradmore (Bodleian Library:Rawl D 287) R0004B/1 Whitlocks of Warkleigh descent from John Lake from Visitation of Devon (edit J.L. Vivian. Exeter 1895) R0005/4 Letter from M.M. Johns to Elmo Ashton re Whitlocks of Langtree, Devon R0006/2 Biography of Brand Whitlock (1869-1934) R0007/3 Whitlocks of Devon parish register extracts R0008/1 Biography of Percy Whitlock (1903-1946) from Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians from M.M. Johns R0009/1 Letter Dd. June 7,1906 from J. Stanley Wedlock of Stanley Bridge, P.E.I.. to John Whitlock of Holdsworthy (sic), Devon R0010/3 Whitlock extracts from Biographical Dictionaries from J.E.I. Wyatt R0011/2 Alumni Oxonienses, The Members of the University of Oxford, 1500-1714 by Joseph Foster from Ruth Spalding R0012/1 Biographical sketch of Thomas Whitlock (1806-1875)'s life by Rev.W.C.Beer R0013/54 Whitlocks of Berkshire descent from John Whitlock & Agnes De la Beche (M about 1454) from J. Wyatt 1969 R0014/ (renumbered) R0015/1 Newspaper clipping re 50th Wedding Anniversary of Mr. -

A Study of English As a Subject in the Curriculum of the College of William and Mary

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1982 A study of English as a subject in the curriculum of the College of William and Mary Jane Agnew Brown College of William & Mary - School of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Jane Agnew, "A study of English as a subject in the curriculum of the College of William and Mary" (1982). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539618324. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.25774/w4-g0qz-df68 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material subm itted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. -

The History of the College of William and Mary from Its Foundation, 1693

1693 - 1870 m 1m mmtm m m m&NBm iKMi Sam On,•'.;:'.. m '' IIP -.•. m : . UBS . mm W3m BBSshsR iillltwlll ass I HHH1 m '. • ml §88 BmHRSSranH M£$ Sara ,mm. mam %£kff EARL GREGG SWEM LIBRARY THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY IN VIRGINIA Presented By Dorothy Dickinson PIPPEN'S a BOOI^ a g OllD STORE, 5j S) 60S N. Eutaw St. a. BALT WORE. BOOES EOUOE' j ESCHANQED. 31 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/historyofcollege1870coll 0\JI.LCkj£ THE HISTORY College of William and Mary From its Foundation, 1693, to 1870. BALTIMOKE: Printed by John Murphy & Co. Publishers, Booksellers, Printers and Stationers, 182 Baltimore Street. 1870. Oath of Visitor, I. A. B., do golemnly promise and swear, that I will truly and faith- fully execute the duties of my office, as a vistor of William and Mary College, according to the best of my skill and judgment, without favour, affection or partiality. So help me God. Oath of President or Professor. I, do swear, that I will well and truly execute the duties of my office of according to the best of my ability. So help me God. THE CHARTER OF THE College of William and Mary, In Virginia. WILLIAM AND MARY, by the grace of God, of England, Scot- land, France and Ireland, King and Queen, defenders of the faith, &c. To all to whom these our present letters shall come, greeting. Forasmuch as our well-beloved and faithful subjects, constituting the General Assembly of our Colony of Virginia, have had it in their minds, and have proposed -

John Stewart Bryan

I944-] OBITUARIES 123 the Class of 1877. Immediately after the death of each member Dr. Allen would bring into my office in the Harvard University Archives the neatly finished docket of the man's correspondence and a formal obituary. It was always with a pleasant word, and never with bitterness or resentment at the ravages of time, that he handed his friends' papers to the University's Charon. After a short sickness Dr. Allen died in Brookline on July 12, 1944. He is survived by a niece, Mrs. Francis P. Coffin, of Schenectady. C. K. S. JOHN STEWART BRYAN John Stewart Bryan, Virginia newspaper publisher and former president of the College of William and Mary, died at Richmond, Virginia, October 16, 1944. He was born at Brook Hill in Henrico County, October 23, 1871, the son of Joseph and Isobel Lamont (Stewart) Bryan. His father, during the War, was one of Mosby's famous raiders and inculcated his son with the Confederate tradition. His boy- hood was spent at Brook Hill and at Laburnum, the estate near Richmond where his father built a home in 1885. After a school education in Richmond and Alexandria, he attended the University of Virginia where he received the degree of A.M. in 1893. He then entered Harvard Law School, to acquire his LL.B. in 1897. Although he studied to become a lawyer, Mr. Bryan soon developed other interests. In 1900 he became associated with his father in publishing the Richmond Times-Dispatch, and in 1908, upon his father's death, he was chosen publisher of the paper. -

1 the Eugene D. Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese Library

The Eugene D. Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese Library Bibliography: with Annotations on marginalia, and condition. Compiled by Christian Goodwillie, 2017. Coastal Affair. Chapel Hill, NC: Institute for Southern Studies, 1982. Common Knowledge. Duke Univ. Press. Holdings: vol. 14, no. 1 (Winter 2008). Contains: "Elizabeth Fox-Genovese: First and Lasting Impressions" by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. Confederate Veteran Magazine. Harrisburg, PA: National Historical Society. Holdings: vol. 1, 1893 only. Continuity: A Journal of History. (1980-2003). Holdings: Number Nine, Fall, 1984, "Recovering Southern History." DeBow's Review and Industrial Resources, Statistics, etc. (1853-1864). Holdings: Volume 26 (1859), 28 (1860). Both volumes: Front flyleaf: Notes OK Both volumes badly water damaged, replace. Encyclopedia of Southern Baptists. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1958. Volumes 1 through 4: Front flyleaf: Notes OK Volume 2 Text block: scattered markings. Entrepasados: Revista De Historia. (1991-2012). 1 Holdings: number 8. Includes:"Entrevista a Eugene Genovese." Explorations in Economic History. (1969). Holdings: Vol. 4, no. 5 (October 1975). Contains three articles on slavery: Richard Sutch, "The Treatment Received by American Slaves: A Critical Review of the Evidence Presented in Time on the Cross"; Gavin Wright, "Slavery and the Cotton Boom"; and Richard K. Vedder, "The Slave Exploitation (Expropriation) Rate." Text block: scattered markings. Explorations in Economic History. Academic Press. Holdings: vol. 13, no. 1 (January 1976). Five Black Lives; the Autobiographies of Venture Smith, James Mars, William Grimes, the Rev. G.W. Offley, [and] James L. Smith. Documents of Black Connecticut; Variation: Documents of Black Connecticut. 1st ed. ed. Middletown: Conn., Wesleyan University Press, 1971. Badly water damaged, replace. -

A Letter from Jefferson to Edward Coles

Educational materials were developed through the Making Master Teachers in Howard County Program, a partnership between Howard County Public School System and the Center for History Education at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. Teacher Page: Resource Sheet #09 Source: Letter From Thomas Jefferson to Edward Coles. Monticello: August 25, 1814, Jefferson’s Farm Book. Note: Edward Coles was born into a wealthy slave-owning family in Albemarle County, Virginia. Coles studied at the College of William & Mary and was convinced that slavery was wrong. He sought for many years to find a way to free the slaves he inherited from his father; one of the wealthiest men in what was then the western frontier of Virginia. He became the second governor of Illinois, serving from 1822 to 1826. He was influential in opposing a movement to make Illinois a slave state in its early years. He often corresponded with Jefferson at Monticello. Document Analysis: 1. How does Jefferson feel about slaves and African-Americans when considering their capabilities as citizens? Jefferson equates African-Americans to children, unable to take care of themselves and destined to become a burden to society as free persons. 2. How does Jefferson react to the possibility that, if slavery is abolished, inter-racial offspring (amalgamation) may occur? It would be a horrible condition, one that which “no lover of his country, no lover of excellence in the human character can innocently consent.” 3. What does Jefferson believe that slaves will do, if they are not used actively as laborers? Non-working slaves could create a problem for the society at large. -

Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 0 MB No 1024-0018 (R11v. Aug. 2002) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This fo1m 1s for use m nomlnatino or r911ues\ing det.ormln"Ot.ons for 1nd ..wu111 ~ies ooo dtsmas see tnslTvQJons In How to CompJele I/le NaliOfl'al Register of Hl~onc Plncos R()9'sfrQ/lon Fom, (Nauonal Reglsler f3ulleun 16A). Compl11te ooch llem t>y mark1119 • (' ,,, th~ appmpr101e tx>ic 01 by eniertng ine 1mo11narion ruqut:Stect It any Item doc,!> nol ctpply to 11\e !)foe>efty be!OQ documeoiea. enrer "NIN for ·not appllcabln • For functions, archllecturol das~lfrcabon m111c,wls . 1111tJ areas of signtflcaoce, entef onlyca1esones ana subcategones from lhe1ns1n1cuons. Placeaddtuonai i,(lbie<- ar,d nana11,-e11oms O"\ conUnuooon :lheets (NPS Form 10-000a} Use-a 1ypew,,1e·. wore processor. or comput~r. to c:omolele all items =~"""""~-~--==:;::~=-================================================================================ 1. Name of Property =-===-========:r::=:::::==:::c:: ___ c:::=--- ------""-~--=c:::::-::::========================:======================= 2. Location not for publication__ x_ c,ly or town r----------------- vicinity N/A state Virginia code _V_A__ county Suny code ----21p code--- =-==== =:d======== ==-::====-=-=-=-====-====------------------====== 3. State/Federal Agency Certification ====-=,..-- ---- ------ As lhe designated authOnty under lhe Nallonal Hlstonc PraseMttron Act as amef'lded. I nereby cart.lfy that this~ nom1na11on __ request ror determination or eligibillly meets the documeotaUoo standards for registenng properties rn the National Register of Histonc Places and meets tne procedural and professlonat requirements set rorth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my Clpinion Uie proper;y .JS,_, meots __ does no1 meet the Natlonal Rag1s1ar Crtterm.