23491 1961 DAT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoirs on the History, Folk-Lore, and Distribution of The

' *. 'fftOPE!. , / . PEIHCETGIT \ rstC, juiv 1 THEOLOGICAL iilttTlKV'ki ' • ** ~V ' • Dive , I) S 4-30 Sect; £46 — .v-..2 SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/memoirsonhistory02elli ; MEMOIRS ON THE HISTORY, FOLK-LORE, AND DISTRIBUTION RACESOF THE OF THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES OF INDIA BEING AN AMPLIFIED EDITION OF THE ORIGINAL SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF INDIAN TERMS, BY THE J.ATE SIR HENRY M. ELLIOT, OF THE HON. EAST INDIA COMPANY’S BENGAL CIVIL SEBVICB. EDITED REVISED, AND RE-ARRANGED , BY JOHN BEAMES, M.R.A.S., BENGAL CIVIL SERVICE ; MEMBER OP THE GERMAN ORIENTAL SOCIETY, OP THE ASIATIC SOCIETIES OP PARIS AND BENGAL, AND OF THE PHILOLOGICAL SOCIBTY OP LONDON. IN TWO VOLUMES. YOL. II. LONDON: TRUBNER & CO., 8 and 60, PATERNOSTER ROWV MDCCCLXIX. [.All rights reserved STEPHEN AUSTIN, PRINTER, HERTFORD. ; *> »vv . SUPPLEMENTAL GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE NORTH WESTERN PROVINCES. PART III. REVENUE AND OFFICIAL TERMS. [Under this head are included—1. All words in use in the revenue offices both of the past and present governments 2. Words descriptive of tenures, divisions of crops, fiscal accounts, like 3. and the ; Some articles relating to ancient territorial divisions, whether obsolete or still existing, with one or two geographical notices, which fall more appro- priately under this head than any other. —B.] Abkar, jlLT A distiller, a vendor of spirituous liquors. Abkari, or the tax on spirituous liquors, is noticed in the Glossary. With the initial a unaccented, Abkar means agriculture. Adabandi, The fixing a period for the performance of a contract or pay- ment of instalments. -

Perspectives of Caste Census: Why It Is Needed Today?

Perspectives of Caste Census: Why it is needed today? By Premendra Priyadarshi1 Up to 1931, the Census of India included caste too. This practice was abandoned in 1941 because of protests by the nationalists, and also because it was considered worthless, misleading and a waste of time and energy. Column for religion was continued till 2001 census. Thereafter it was felt to be divisive and abandoned from 2011 census. Yet recently, there have been demands in political establishment for and against the caste census and the Union Government seems to be succumbing to pressures. It is desirable that we examine the perspectives of caste census. Why caste abandoned from census in 1941 The most important reason for abandonment of caste census was the ‗worthlessness‘ of the whole exercise because of inconsistency in caste names, which were not fixed and varied between districts, and with time, high incidence of unreliability of individuals‘ statement about caste etc. The Census Commissioner of India for 1931, J.H. Hutton noted, ―Sorting for caste is really worthless unless nomenclature is sufficiently fixed to render the resulting totals close and reliable approximations. Had caste terminology the stability of religious returns, caste sorting might be worthwhile. With the fluidity of current appellations it is certainly not… 227,000 Ambattans have become 10,000, Navithan, Nai, Nai Brahman, Navutiyan, Pariyari claim about 140,000—all terms unrecorded or untabulated in 1921.‖1 Only explanation for this could be that most of the Ambattans of 1921 changed into some other caste. Similarly, the number of Marathas in Central Provinces and Berar increased from 93,901 in 1911, to 206,144 in 1921.2 This more than 110% increase in number can be explained by the mass mobilization of Kunbis (Kurmi-s) to Marathas during the period. -

CASTE SYSTEM in INDIA Iwaiter of Hibrarp & Information ^Titntt

CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of iWaiter of Hibrarp & information ^titntt 1994-95 BY AMEENA KHATOON Roll No. 94 LSM • 09 Enroiament No. V • 6409 UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF Mr. Shabahat Husaln (Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY & INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1995 T: 2 8 K:'^ 1996 DS2675 d^ r1^ . 0-^' =^ Uo ulna J/ f —> ^^^^^^^^K CONTENTS^, • • • Acknowledgement 1 -11 • • • • Scope and Methodology III - VI Introduction 1-ls List of Subject Heading . 7i- B$' Annotated Bibliography 87 -^^^ Author Index .zm - 243 Title Index X4^-Z^t L —i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. Shabahat Husain (Chairman), who inspite of his many pre Qoccupat ions spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step, during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher Mr. Hasan Zamarrud, Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for the encourage Cment that I have always received from hijft* during the period I have ben associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respect teachers of my department professor, Mohammadd Sabir Husain, Ex-Chairman, S. Mustafa Zaidi, Reader, Mr. M.A.K. Khan, Ex-Reader, Department of Library & Information Science, A.M.U., Aligarh. I also want to acknowledge Messrs. Mohd Aslam, Asif Farid, Jamal Ahmad Siddiqui, who extended their 11 full Co-operation, whenever I needed. -

D. D. Kosambi History and Society

D. D. KOSAMBI ON HISTORY AND SOCIETY PROBLEMS OF INTERPRETATION DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF BOMBAY, BOMBAY PREFACE Man is not an island entire unto himself nor can any discipline of the sciences or social sciences be said to be so - definitely not the discipline of history. Historical studies and works of historians have contributed greatly to the enrichment of scientific knowledge and temper, and the world of history has also grown with and profited from the writings in other branches of the social sciences and developments in scientific research. Though not a professional historian in the traditional sense, D. D. Kosambi cre- ated ripples in the so-called tranquil world of scholarship and left an everlasting impact on the craft of historians, both at the level of ideologi- cal position and that of the methodology of historical reconstruction. This aspect of D. D. Kosambi s contribution to the problems of historical interpretation has been the basis for the selection of these articles and for giving them the present grouping. There have been significant developments in the methodology and approaches to history, resulting in new perspectives and giving new meaning to history in the last four decades in India. Political history continued to dominate historical writings, though few significant works appeared on social history in the forties, such as Social and Rural Economy of North- ern India by A. N. Bose (1942-45); Studies in Indian Social Polity by B. N. Dutt (1944), and India from Primitive Communism to Slavery by S. A. Dange (1949). It was however with Kosambi’s An Introduction to the study of Indian History (1956), that historians focussed their attention more keenly on modes of production at a given level of development to understand the relations of production - economic, social and political. -

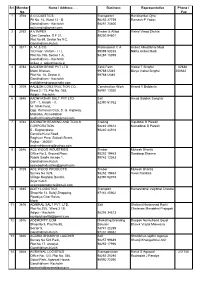

Srl. Member No. Name / Address . . . Business Representative Phone

Srl. Member Name / Address . Business Representative Phone / No. Fax 1 3768 A G LOGISTICS Transporter Harishankar Ojha Plt No. 16, Ward 12 - B, 98252 27739 Ramesh P Yadav Gandhidham - Kachchh 98251 74800 [email protected] 2 3762 A V IMPEX Timber & Allied Vishal Vinod Shukla Ojas Complex, S F 21, 98250 84501 Plot No 69, Sector No 9 C, Gandhidham Kutch 3 3511 A. M. & CO. Professional C A Aniket Alkeshbhai Modi 1st Floor, Vikram - I I I, 99099 58338 Nikita Aniket Modi Plot No.155, Sector 1 A, 94283 10399 Gandhidham - Kachchh [email protected] 4 3783 AADESH BRINE PVT LTD Tank Farm Vishal T Singhvi 02836 Maitri Bhavan, 9978812345 Divya Vishal Singhvi 250662 Plot No. 18, Sector 8, 9978812345 Gandhidham - Kachchh [email protected] 5 3709 AADESH CONSTRUCTION CO. Construction Work Anand V Baldania Ward 2 / 13, Plot No. 365, 98981 13020 Adipur - Kachchh 6 3645 AADHYASHRI SALT PVT LTD Salt Amad Siddhik Sanghar G F - 1, Aarohi - 3, 82380 61762 Nr. Nikki Ford, Opp. Karnavati Club, S. G. Highway, Makarba, Ahmedabad [email protected] 7 3784 AADINATH BEARING AND TOOLS Trading Vipulbhai B Parekh CORPORATION 98242 49614 Kamalbhai B Parekh 5 - Raghuvipara, 98240 44918 Garedia Kuva Road, Raghuvir Para, Sidivali Street, Rajkot - 360001 [email protected] 8 3546 ACE WOOD INDUSTRIES Timber Mukesh Bhartia Office No 3, Ground Floor, 98252 19463 Sandeep Sharma Riddhi Siddhi Arcade 1, 99743 12343 Gandhidham Kutch [email protected] 9 3729 ACE WOOD PRODUCTS Timber Mukesh Bhartia Survey No 32/9, 98252 19463 Vivek Harlalka Village Meghpar Borichi, 82380 02078 Anjar Kutch [email protected] 10 3585 ADITY LOGISTICS Transport Rameshbhai Valjibhai Chavda Shop No 13, Balaji Shopping, 97142 45902 Pipadiya Char Rasta, Morbi 11 3616 ADMIRAL SALT PVT. -

Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES CASTE, KINSHIP AND SEX RATIOS IN INDIA Tanika Chakraborty Sukkoo Kim Working Paper 13828 http://www.nber.org/papers/w13828 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 March 2008 We thank Bob Pollak, Karen Norberg, David Rudner and seminar participants at the Work, Family and Public Policy workshop at Washington University for helpful comments and discussions. We also thank Lauren Matsunaga and Michael Scarpati for research assistance and Cassie Adcock and the staff of the South Asia Library at the University of Chicago for their generous assistance in data collection. We are also grateful to the Weidenbaum Center and Washington University (Faculty Research Grant) for research support. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2008 by Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Caste, Kinship and Sex Ratios in India Tanika Chakraborty and Sukkoo Kim NBER Working Paper No. 13828 March 2008 JEL No. J12,N35,O17 ABSTRACT This paper explores the relationship between kinship institutions and sex ratios in India at the turn of the twentieth century. Since kinship rules varied by caste, language, religion and region, we construct sex-ratios by these categories at the district-level using data from the 1901 Census of India for Punjab (North), Bengal (East) and Madras (South). -

Annexure V - Caste Codes State Wise List of Castes

ANNEXURE V - CASTE CODES STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE TAMIL NADU CODE CASTE 1 ADDI DIRVISA 2 AKAMOW DOOR 3 AMBACAM 4 AMBALAM 5 AMBALM 6 ASARI 7 ASARI 8 ASOOY 9 ASRAI 10 B.C. 11 BARBER/NAI 12 CHEETAMDR 13 CHELTIAN 14 CHETIAR 15 CHETTIAR 16 CRISTAN 17 DADA ACHI 18 DEYAR 19 DHOBY 20 DILAI 21 F.C. 22 GOMOLU 23 GOUNDEL 24 HARIAGENS 25 IYAR 26 KADAMBRAM 27 KALLAR 28 KAMALAR 29 KANDYADR 30 KIRISHMAM VAHAJ 31 KONAR 32 KONAVAR 33 M.B.C. 34 MANIGAICR 35 MOOPPAR 36 MUDDIM 37 MUNALIAR 38 MUSLIM/SAYD 39 NADAR 40 NAIDU 41 NANDA 42 NAVEETHM 43 NAYAR 44 OTHEI 45 PADAIACHI 46 PADAYCHI 47 PAINGAM 48 PALLAI 49 PANTARAM 50 PARAIYAR 51 PARMYIAR 52 PILLAI 53 PILLAIMOR 54 POLLAR 55 PR/SC 56 REDDY 57 S.C. 58 SACHIYAR 59 SC/PL 60 SCHEDULE CASTE 61 SCHTLEAR 62 SERVA 63 SOWRSTRA 64 ST 65 THEVAR 66 THEVAR 67 TSHIMA MIAR 68 UMBLAR 69 VALLALAM 70 VAN NAIR 71 VELALAR 72 VELLAR 73 YADEV 1 STATE WISE LIST OF CASTES STATE MADHYA PRADESH CODE CASTE 1 ADIWARI 2 AHIR 3 ANJARI 4 BABA 5 BADAI (KHATI, CARPENTER) 6 BAMAM 7 BANGALI 8 BANIA 9 BANJARA 10 BANJI 11 BASADE 12 BASOD 13 BHAINA 14 BHARUD 15 BHIL 16 BHUNJWA 17 BRAHMIN 18 CHAMAN 19 CHAWHAN 20 CHIPA 21 DARJI (TAILOR) 22 DHANVAR 23 DHIMER 24 DHOBI 25 DHOBI (WASHERMAN) 26 GADA 27 GADARIA 28 GAHATRA 29 GARA 30 GOAD 31 GUJAR 32 GUPTA 33 GUVATI 34 HARJAN 35 JAIN 36 JAISWAL 37 JASODI 38 JHHIMMER 39 JULAHA 40 KACHHI 41 KAHAR 42 KAHI 43 KALAR 44 KALI 45 KALRA 46 KANOJIA 47 KATNATAM 48 KEWAMKAT 49 KEWET 50 KOL 51 KSHTRIYA 52 KUMBHI 53 KUMHAR (POTTER) 54 KUMRAWAT 55 KUNVAL 56 KURMA 57 KURMI 58 KUSHWAHA 59 LODHI 60 LULAR 61 MAJHE -

Review of Literature

Chapter 2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE Review of Literature Review of Literature Clothing reflects about one’s membership in a culture and of the many groups he/ she belongs or relates to within a culture. Costumes forms an important element amongst all the cultural expressions defining one’s identity in India. Eicher writes ethnic dress is a notable aspect of ethnicity. Again, Claus and Korom states that a folkloristic or an ethnographic study includes the study of culture, history and psychology. These represent the three fundamental dimensions in which expression exists. What forms and shapes any expression is the past (history, tradition), the outer context (Culture) and the inner motivation (psychology). And there are always other pertinent lines of inquiry- political structure, economics, geography and others (Claus P. and Korom F.,1991: 41). Therefore, the present chapter aims to take a preliminary glimpse of the factors coming under the purview of the subject under study. 2.1. Theoretical review 2.1.1. Accounts on Indian Cotton Textiles: History, trade, production and evolution 2.1.2. Salience of folk costumes and textiles in India 2.1.3. Gujarati textiles: Production, trade and consumption 2.1.4. Traditional draped garments of men in India 2.1.5. Geography and morphology of producers and patrons 2.1.5.1. The Locales: Geography and culture (Saurashtra, Kachchh, North Gujarat, Ahmedabad) 2.1.5.2. People: (Vankar, Barot, Vaniya, Bharward, Rabari, Charan, Ahir) 2.1.6. Cultural contexts of commodities: Importance of products in social life 2.1.7. Handloom Industry in India 2.1.7.1. -

Wealth Inequality, Class and Caste in India, 1951-2012 Nitin Kumar Bharti

Wealth Inequality, Class and Caste in India, 1951-2012 Nitin Kumar Bharti Masters Thesis Report Supervisor: Professor Thomas Piketty (PSE) Referee : Professor Abhijit Banerjee (MIT) June 28, 2018 Abstract This research makes two main contributions. First, I combine data from wealth surveys (NSS-AIDIS) and millionaire lists to produce wealth inequality series for India over the 1961-2012 period. I find a strong rise in wealth concentration in recent decades, in line with recent research using income data. E.g. the top 10% wealth share rose from 45% in year 1981 to 68% in 2012, while the top 1% share rose from 27% to 41%. Next, I gather information from censuses and surveys (NSS AIDIS and consumption, IHDS, NFHS) in order to explore the changing relationship between class and caste in India and the mechanisms behind rising inequality. Assortative mating appears to be very high in India, both at the caste level and at the education level (though not hugely larger than than in Western countries at the education level). I stress the limits of our knowledge and indicate possible lines of future research, particularly regarding the interplay between assortative mating and inequality dynamics. JEL Classification: J00 D63 N30 Keywords: Wealth; Inequality; India; Caste; Assortative Mating; Marriage 1 Contents 1 Introduction 5 2 Literature 6 3 Data 7 3.1 NSS- All India Debt and Investment Survey (AIDIS)............................8 3.2 NSS- Consumption Surveys.......................................... 10 3.3 IHDS- Indian Human Development Survey.................................. 10 3.4 NFHS- National Family and Health Survey................................. 12 4 Demographic Profile 12 4.1 Population Share- Rural Urban divide................................... -

[email protected] Mota Varachha, Surat

Surat Municipal Corporation Registered Proffesional Detail - Architect Page 1 of 29 Run Date : 22/06/2021 Sr License Number License Name Address Phone Number Email No. 1 TDO/AR/1 Arunkumar Krishnnath Pradhan "Shilpseva",Arvind Nivas,near Athwa 9821153100 gate,Surat 2 TDO/AR/2 Parikshitlal Manilal Talati "Parijya"Shayamsadan nanpura, near 9426152862 ar_talati29rediffmail.com Makkaipul,Surat 3 TDO/AR/3 Hemendra G Parikh 101,Yashaka, near Kadiwala school,Ring Road,Surat 4 TDO/AR/4 Rashmikant Punamchad Dalwadi "" Archi Mahmud Manzil, Makkaipul, 9825917930 Surat 5 TDO/AR/5 Kanubhai Vallabhbhai Mistri Sayagi Road,Navsari 9825322830 [email protected] 6 TDO/AR/6 Bomi Khanshadji Dangar 407,Gajar Bungalo,Athawalines, 9327334798 Surat 7 TDO/AR/7 Kishor Chimanlal Hathiwala 206,Nirman Bhavan, Majura gate, 9824029639 [email protected] RingRoad.Surat 8 TDO/AR/8 Harikrushan Aaditram Parmar Khangadsheri, Salabatpura,Surat 9825127872 [email protected] 9 TDO/AR/9 Gulamrasul Rahematula Bala 4/001/1 Asatodia Gove.socity,Elice Brige,Ahemadabad 10 TDO/AR/10 Mahendra Nemichand Kuwadia 23,Third Floor,Lohana Bld,Ravpura,Vadodra 11 TDO/AR/11 Kalyanchand Nemchand Shah 2/B First Floor, Ishwarchand Devgi Bhimgilen,Kandivali West,Mumbai 12 TDO/AR/12 Haresh Jayantilal Mahadevwala "Aayojan", Himani Appt, Majuragate, 9924211011 [email protected] Surat. 13 TDO/AR/13 Kanubhai Orachavlal Shah "Hirabag"Saidapura, Surat 14 TDO/AR/14 Bharat Thakordas Sheth 4, "Nisarg", Nr. Dimple Row Houses, 9825144308 [email protected] B/H Surat City Gymkhana, Piplod, Surat. 395007 15 TDO/AR/15 Babubhai Parsottambhai Rathod 19,Prakashkung NetagiShubhshchandra Road,Mulund West, Mumbai 16 TDO/AR/16 Maharshi Manharlal Vimavala 9/1428 Hawadia Chakala,Ambaji 2615601610 Road, Surat 17 TDO/AR/17 Kishorchandra Amarchandra Kapadia Reshamwala Bld. -

The Caste System As We Know, Is Both Hinduism And

"The caste system as we know, is It must go if both Hinduism and India are lo Jive day to day." -Mahatma Gandhi. "In th~ context of soc1ety to·day the caste system and much that goes with it are wholly incompatiblr, reactionary, JCstrictive, and barriers to progress. There can be no equahty 1n status and opportunity within its framework, nor can thc1e be political democracy, and much less economic democrncy. Between these two conceptions conflict is inherent and only one of them can survive." -Pandit Shrl Jawaharlal Nehru. "The caste system is the main hindrauce in the way of achieving our goal of establishing casteless and eg'llitarian society. Identifieati<ln of soctally and educationally backward classes in terms o: caste is perpetuation of ·the evils of the caste system. Sooner we get lid of it the better for the nation." -Commission, CONTENTS VOLUME-I Paragraph Paget ' No. IntrGduction I, • •. ' [xv to xvii] . ,. ' Cbapter-1 • • Summary of the relevant provisiQns,of1 the C:onsti~ 1 tution of India providing for the promo:ion of ' ' educational and econo:n.ic interests and· the advance ment of sopially and. educatio®Uy backwar~ classes and other weaker sections of the society. The object of Articles 15(4) and 16(4) is to achieve 3 2 '. equality by removing inequality. The problem of determining who are socially and 7 3 educationally backward· is very co'mplex. • 1 , I Chapter-II The Casto .ey.stc;m ill' 'India... - 4 •· Caste . system, the main. oa.w;o... of• thei deplorablw "• 1 4 cond,ti~ns of .our mass\ls. -

Report of Haryana Backward Classes Commission

I N D E X Sr. CONTENTS Page No. No. 1. Preface iii 2. History of Backward Classes Movement in Haryana 1–3 3. Acknowledgements 4 4. Identification of Backwards 5 5. Determination of Backward Classes 6–7 6. Central Backward Commission 8–19 7. State Commissions and their recommendations 20–26 8 Constitution of Harayana Backward Classes Commission 27 9 Detail of representations submitted to the Commission 28–28A 10 Format and criteria for determining social, educational, economical 29–35 Backwardness. 11 Estimated Sharing & Breakup of the Sample 36–41 12 Visit by the Commission of various District Headquarters in Haryana to 42–68 hear and ascertain public view 13. Survey Report of Maharishi Dayanand University, Rohtak 69–113 14. Consideration for grant of Reservation 114–148 15. Recommendations of the Commission 149–151 PREFACE A great secular country on the world map is known by different names like ‘India’, ‘Bharat’, ‘Hindustan’, ‘Jambu Deepay Bharat Khandey’. The land of this country is also called as ‘Dev Bhoomi’. Its history is ancient and this land gave birth to great Saints, Scholars, Reformers, and Artisans etc. This country conveyed the message of ‘co-existence’, all over the world. The sword of ‘non-violence’ used by Mahatma Gandhi ‘The Father of the Nation’ to get India free from British Rule is praised all over the world. History is the witness that its rich heritage and hard labour of the people of this country had made this country as ‘Sone ki Chiriya’ which attracted the invaders to rob/ruin and to rule over this country.